Stephen Shore arrived at photography with the certainty of a prodigy and the curiosity of a born observer. Born in New York City in 1947, he received his first darkroom kit at the age of six and began teaching himself the craft that would define his life's work. By the time he was ten, a copy of Walker Evans' American Photographs had entered his hands, and the trajectory was set. At fourteen, he presented prints to Edward Steichen at the Museum of Modern Art, and Steichen acquired three of them for the permanent collection. It was the kind of beginning that borders on myth, yet for Shore it was simply the logical start of an ongoing investigation into how photographs function as pictures and as documents of seeing.

Three years later, Shore walked into Andy Warhol's Factory and found an environment that would reshape his thinking about art and its relationship to the everyday. Between 1965 and 1967, the young photographer moved freely through Warhol's orbit, capturing Edie Sedgwick, The Velvet Underground, and the production of screen tests in intimate black-and-white frames. The experience was less about subject matter than about method. Watching Warhol work taught Shore something fundamental about serial imagery, about repetition, and about the strange power of directing aesthetic attention toward the ordinary. That lesson would animate the rest of his career.

In 1971, Shore became the first living photographer to receive a solo exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York since Alfred Stieglitz four decades earlier. He was twenty-three years old. The black-and-white work in that show was accomplished, but it was what came next that truly altered the medium. Shore turned to colour. At a time when serious art photography was overwhelmingly monochrome, he began making small-format colour prints with a Rollei 35mm camera, treating the quotidian details of American life with the same directness that Warhol brought to soup cans and Brillo boxes.

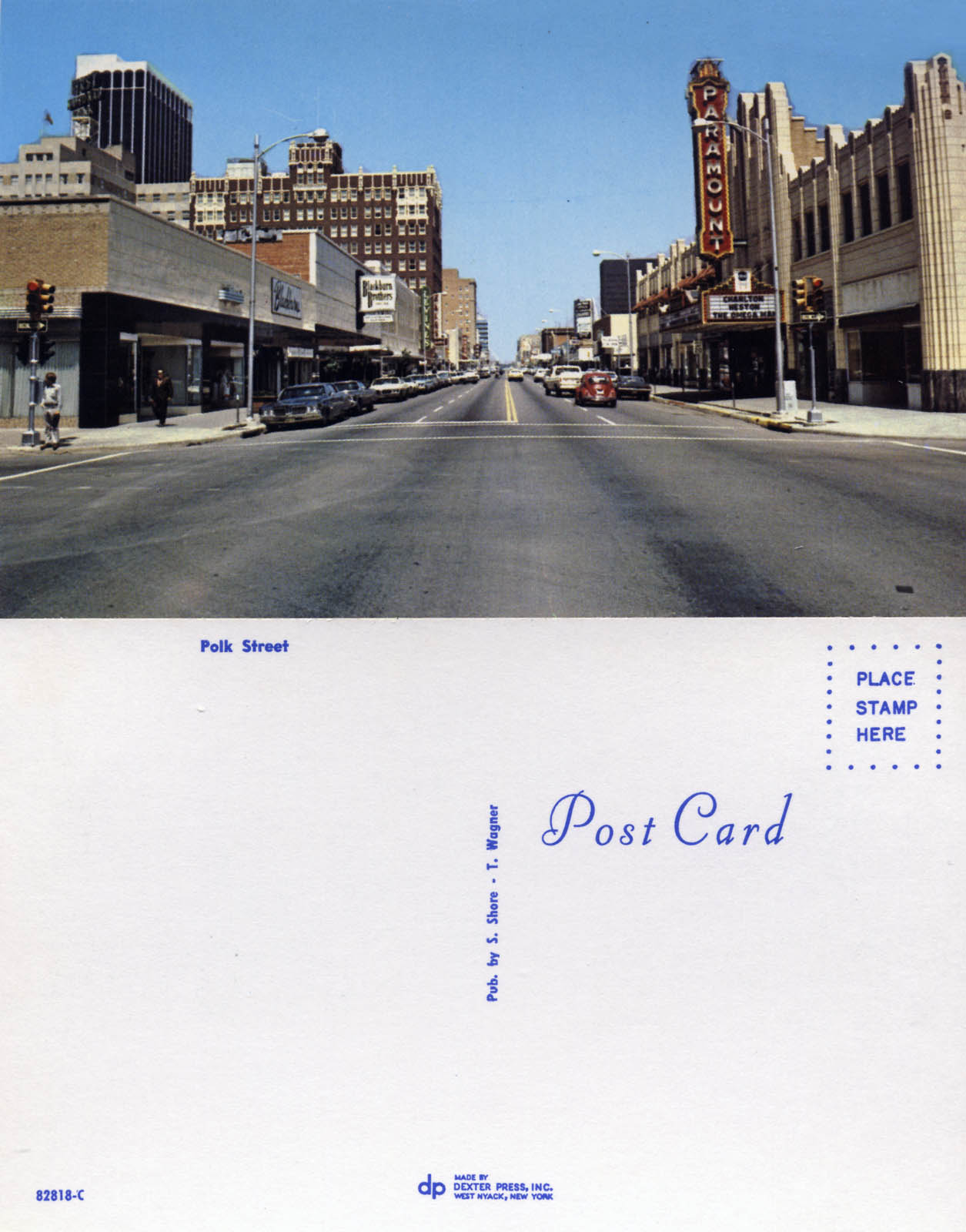

The result was American Surfaces, a body of work produced between 1972 and 1973 during a road trip from New York to Amarillo, Texas. Shore photographed everything: the meals he ate, the beds he slept in, the strangers he met in diners, the empty roads stretching toward distant horizons. Shown at Light Gallery in New York, the 174 images were deliberately unadorned and snapshot-like. Critics accustomed to the formality of gallery photography were uncertain what to make of them. In retrospect, American Surfaces reads as a remarkably prescient document, anticipating by decades the way a generation would later use social media to record daily experience with compulsive regularity.

Shore soon moved to a large-format 8x10 view camera, and the shift transformed his practice. The cumbersome apparatus demanded patience and deliberation. Every exposure became an act of conscious composition, the photograph no longer a snapshot but an architectural arrangement of colour, light, and spatial depth. From this slower, more considered process emerged Uncommon Places, the series of images taken between 1973 and 1981 that many consider his masterwork. Photographing gas stations, intersections, motel rooms, parking lots, and small-town streets across North America, Shore revealed a landscape that was simultaneously unremarkable and visually extraordinary. Each frame was saturated with colour and dense with information, inviting the viewer to look and look again.

The publication of Uncommon Places in 1982 by Aperture cemented Shore's place alongside William Eggleston as one of the two photographers most responsible for establishing colour as a legitimate medium for art photography. Their achievement now feels so total that it is difficult to imagine a time when it was controversial, but in the 1970s colour was viewed by much of the art world as the domain of commercial and amateur photography. Shore's work, together with Eggleston's, permanently dismantled that hierarchy.

Shore's influence on subsequent generations has been immense. Photographers including Andreas Gursky, Thomas Struth, Candida Hofer, Martin Parr, Joel Sternfeld, and Nan Goldin have each acknowledged debts to his practice. The students of Bernd and Hilla Becher at the Kunstakademie Dusseldorf absorbed Shore's lessons in colour and large-format composition, carrying them forward into the monumental photographic tableaux of the 1990s and 2000s. His written work, particularly The Nature of Photographs, published by Phaidon, has become a foundational text for understanding the formal properties of photographic images.

Since 1982, Shore has directed the Photography Program at Bard College in New York's Hudson Valley, shaping successive generations of artists. He holds the title of Susan Weber Professor in the Arts. More than twenty-five books bear his name, including Uncommon Places: The Complete Works, the Phaidon Contemporary Artists retrospective monograph, and Transparencies: Small Camera Works 1971–1979. In 2017, the Museum of Modern Art mounted a comprehensive career retrospective that traced his journey from the Factory photographs through his most recent digital and Instagram work.

What distinguishes Shore from many of his contemporaries is the sustained coherence of his vision. Across six decades and multiple formats — 35mm, 8x10, digital, even Instagram — his eye has remained consistently drawn to the surfaces of the everyday world, finding in its gas stations and grid-plan streets a visual richness that rewards patient attention. He does not dramatise his subjects. He does not sentimentalise them. He simply looks, with a clarity and precision that make the viewer see what was always there.