Review by Aperture:

"If looking at photographs is a pleasurable activity, it is pleasurable in a complex, transformative, frequently unsettling sense. It is not pleasure unalloyed, for no profound pleasure is pure…Like many truly enriching pleasures…photography has its dark, troubling, even dangerous aspects. –Gerry Badger

The Pleasures of Good Photographs is an intellectual and aesthetic excursion led by Gerry Badger, one of the field's eminent critics and popular writers and the author of more than a dozen books including both volumes of The Photobook: A History. In this new volume of essays, Badger offers insight into some of his favorite images, artists and themes, drawing upon nearly three decades of experience writing and thinking about photography. With deep discernment and a readable blend of scholarly finesse and wit, Badger elucidates works by dozens of photographers, from Dorothea Lange and Eugène Atget to Martin Parr, Luc Delahaye, Susan Lipper and Paul Graham. Among the broader topics discussed are the photobook, where Badger believes photography sings its loudest and most complex song, and Photoshop's role in art-making. An interlude at the heart of the book pairs the author's evocative meditations with nearly a dozen particular images. Alongside some of Badger's classics, The Pleasures of Good Photographs showcases primarily new essays, making it an important addition to the canon of photographic writing."

Sample read on Amazon:

QUOTES FROM BOOK

“As Jenkins pointed out in his introduction to the exhibition’s catalog, the difference between artist Ed Ruscha’s Twentysix Gasoline Stations or the Bechers’ cooling towers, and photographer John Schott’s series documenting hotels along Route 66 is both fundamental and significant. Schott himself, acutely aware of the distinction, summarized it with admirable brevity: “[ Ruscha’s pictures] are not statements about the world through art, they are statements about art through the world.” 6”

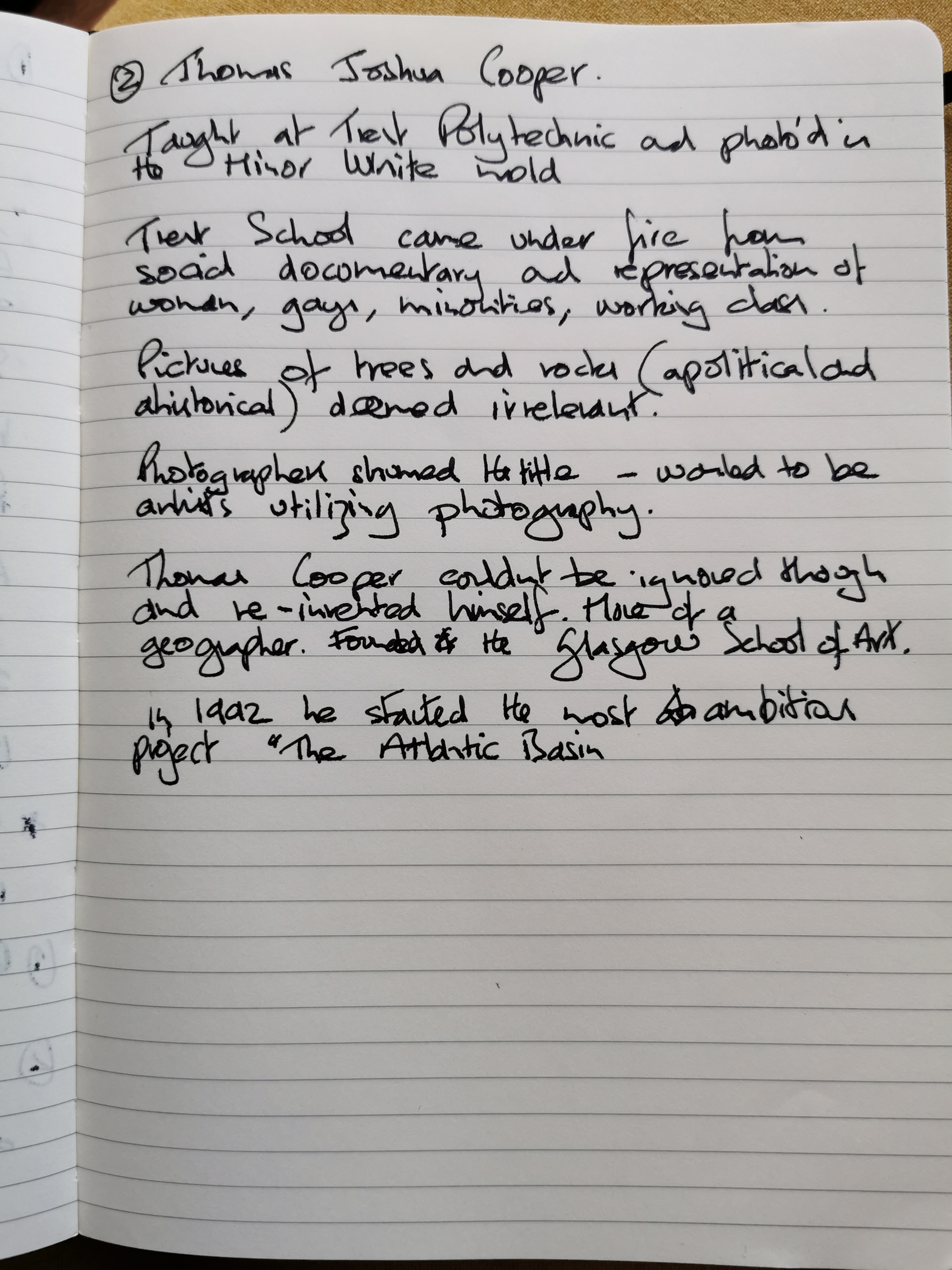

“The quiet photographer then, remains a photographer, and would seek to be recognized as such, though undoubtedly seen to be practicing an independent form of artistic expression. The crucial difference remains one of voice. The voice of the quiet photographer remains modest because his or her referent is not the art scene, but the world.”

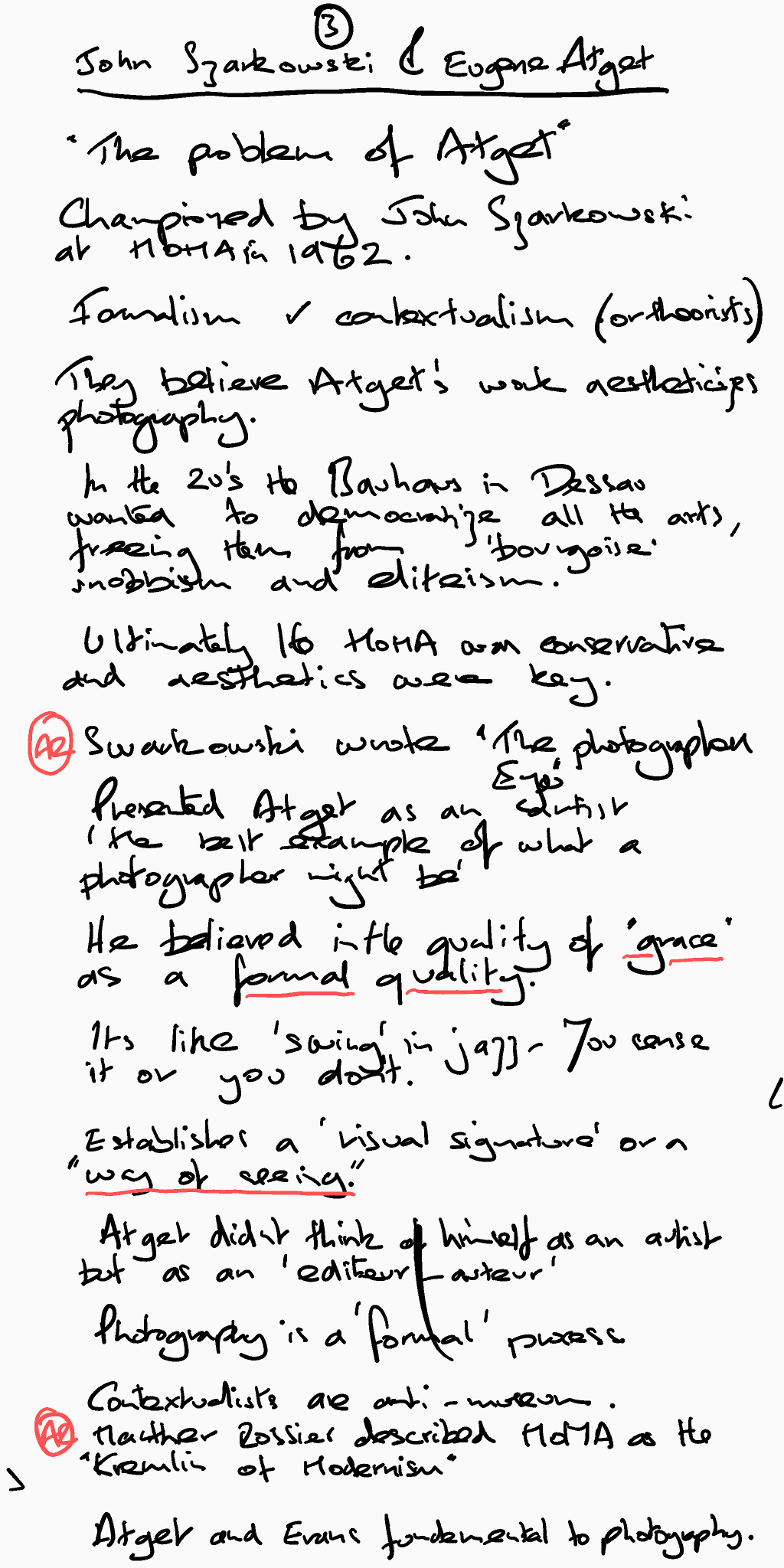

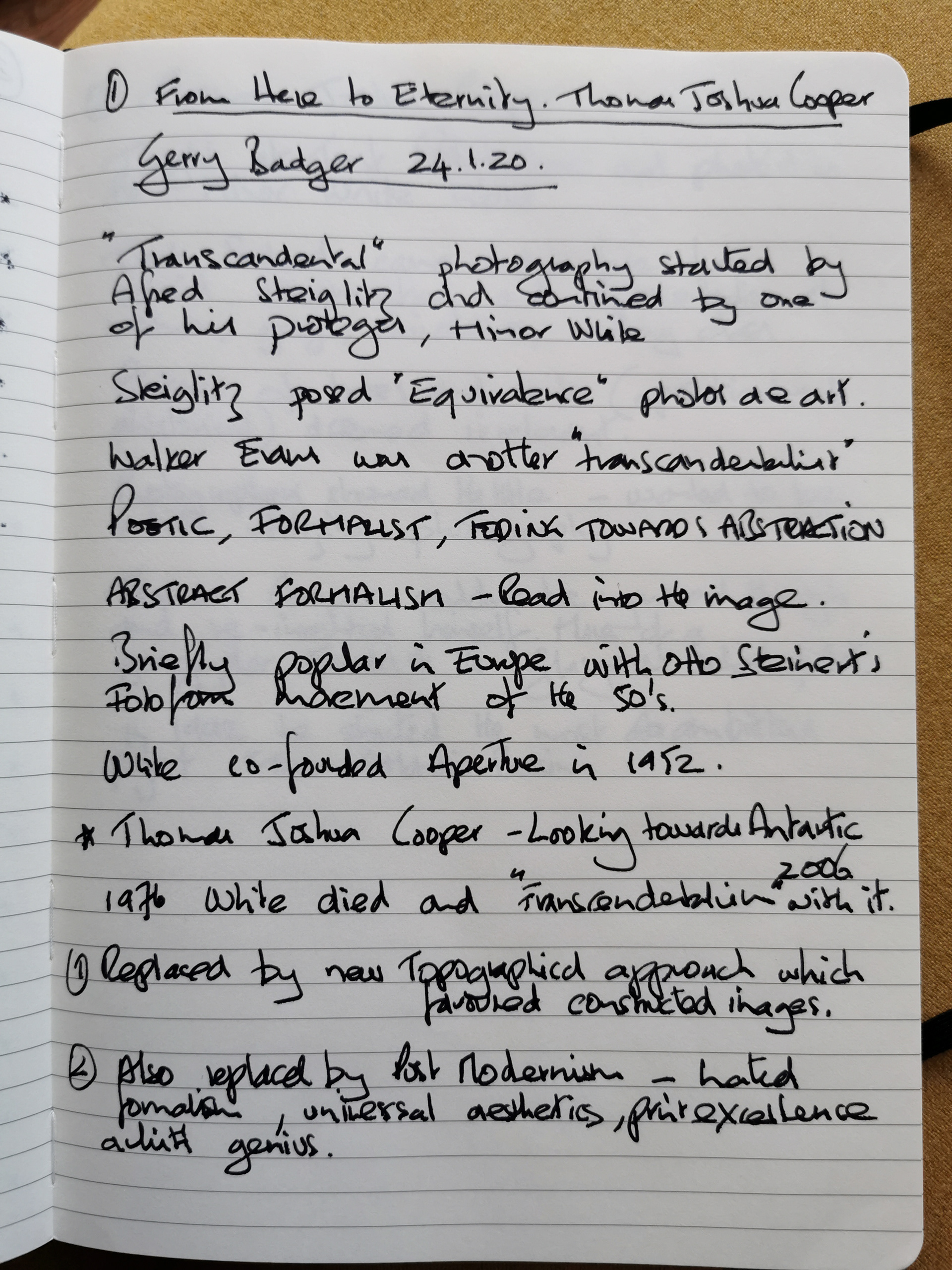

“Postmodern photography however—photography by “artists utilizing photography”—was international in scope and emanated from the art gallery, not the photographic gallery or under the patronage of John Szarkowski.”

“It was not that Szarkowski specifically ignored women photographers—we are back here to my opening remarks, and he of course promoted Arbus—but the kind of documentary, usually street-based photography that he espoused was largely a male preserve. It was also a New York thing. The photographers he proposed as the most important of their day—Arbus, Friedlander, and Winogrand—lived on his doorstep, and had an easy entrée to the Modern, although as Szarkowski himself complained, he did not “make” their careers, he merely recognized their talent and encouraged it. Nevertheless, Szarkowski had become the leading arbiter of taste in early ’70s photography, not solely because of his position at MoMA (not exactly a hindrance) but because he had such strong views about the medium, and was able to articulate them so persuasively through his elegant writings. Meanwhile, the women were elsewhere, many miles away from New York—in the Midwest, in the Southwest, in California—and they were making anything but straight photographs. They weren’t out on the street photographing “to find out what the world looks like in a photograph.” They were in the darkroom or the studio, employing a great variety of photographic techniques, making staged tableaux, and exploring issues like the self, identity, memory, and desire. The kind of photography many of them practiced was not the MoMA-approved variety—largely phenomenological, primarily documentary in mode if not intent—but represented the beginnings of an alternative tradition, parallel to the kind of art that was beginning to be referred to as conceptual. And, when certain European ideas in critical theory, such as semiotics and structuralism, were translated into American practice, the term postmodernism arrived on the scene in the early ’70s, and became the great artistic buzzword toward the end of the decade.”

“The first photobook was not William Henry Fox Talbot’s The Pencil of Nature, 3 but Anna Atkins’s Photographs of British Algae: Cyanotype Impressions. 4 The first part of her epic work, ten years in the making, predated Talbot’s by a few months. However, some scholars have argued that Algae, privately distributed to friends in a very few copies, should be regarded as an album rather than a book available for public purchase. The Pencil was sold by public subscription, so in certain quarters, Talbot is awarded the palm, although clearly Atkins, as much as Talbot, had the crucial idea of putting a cogent group of photographic images between covers.”

“Walker Evans once said that the best photographic education comes from “informal contact with a master,” 1 and I feel that he was right. I learnt more from hanging out with Garry Winogrand in Los Angeles for two or three memorable days in 1980, than from a year of college lectures. I would add that quality time spent with any great photobook might also be classed as “informal contact with a master.””

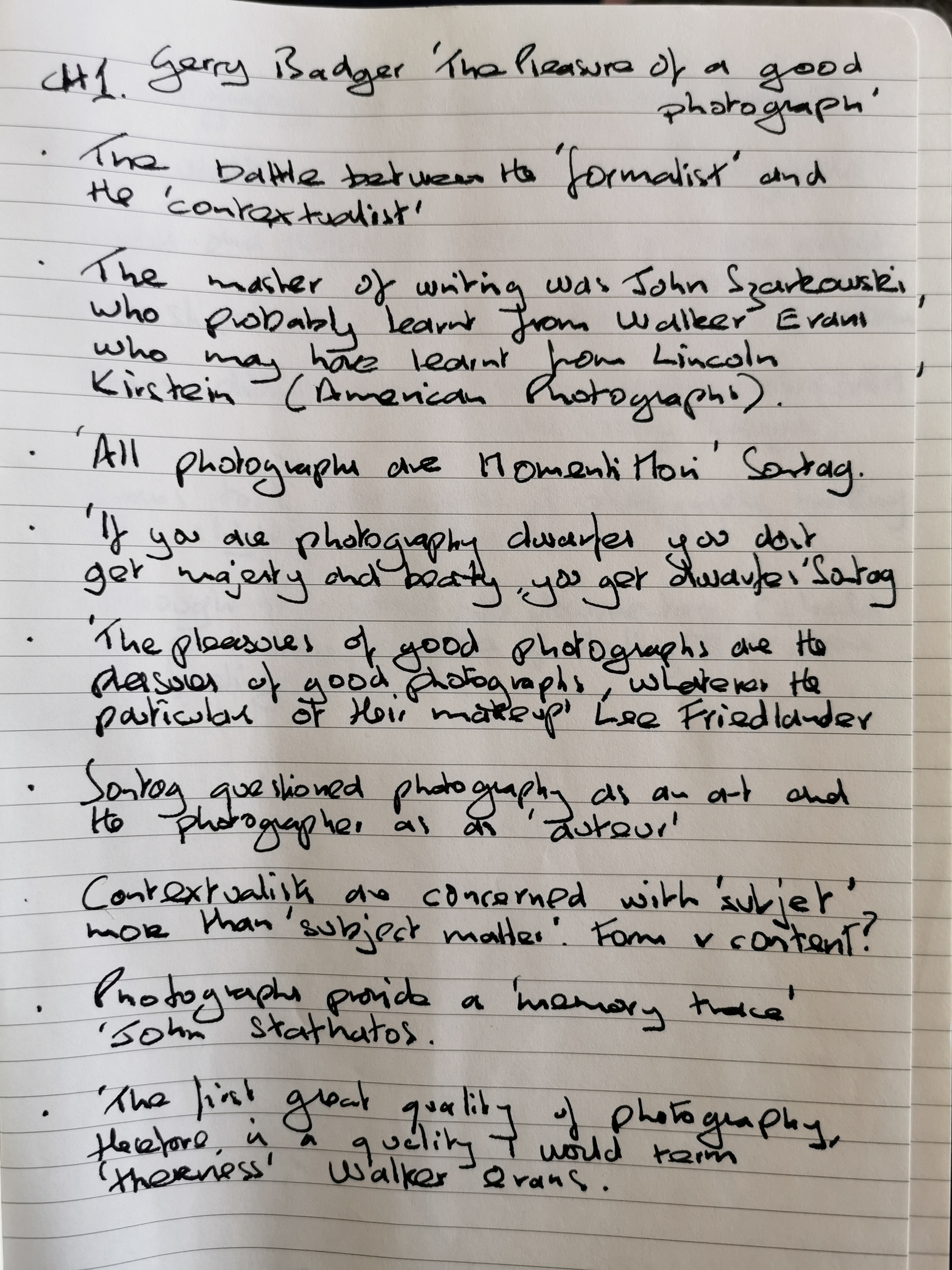

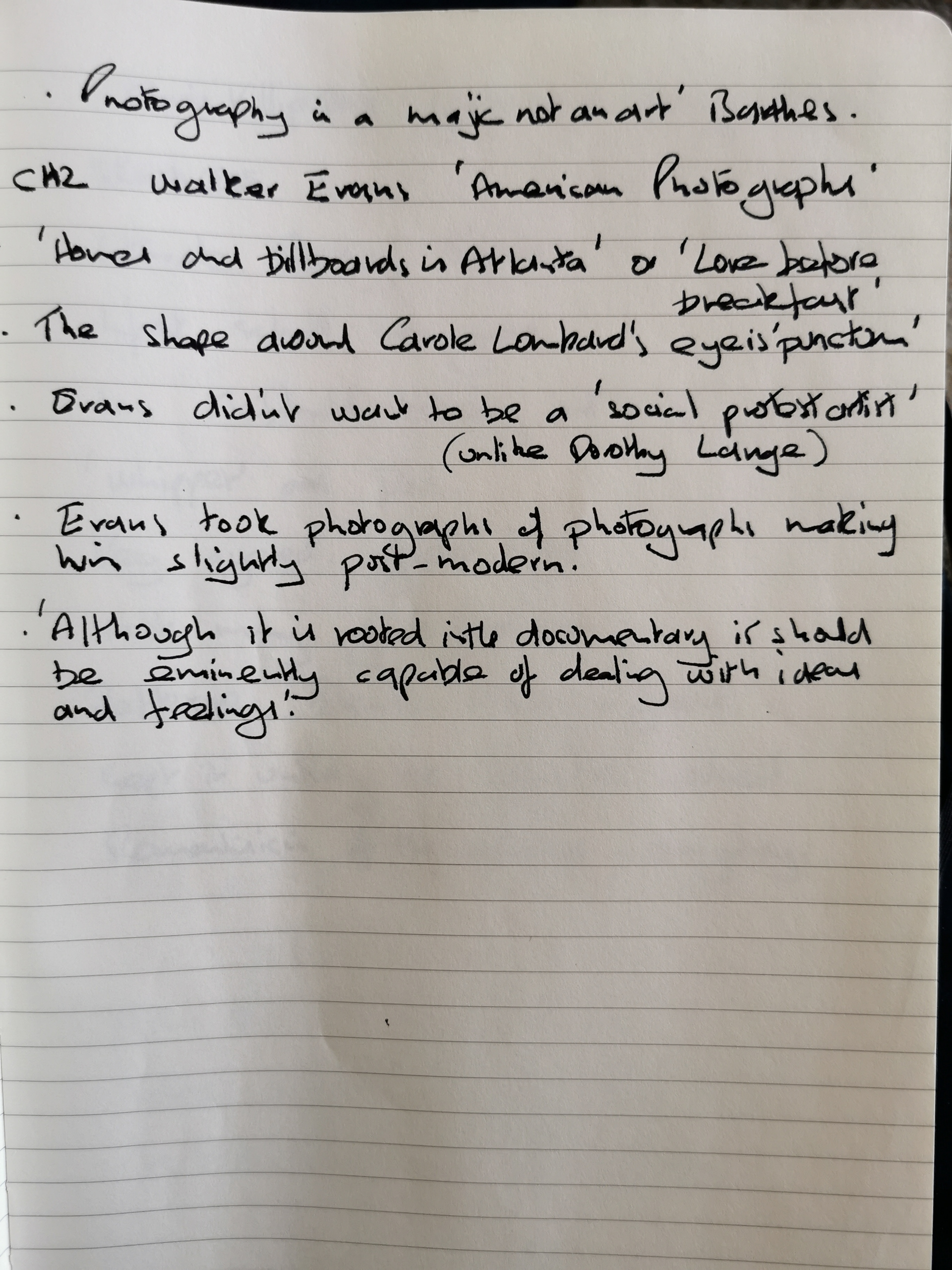

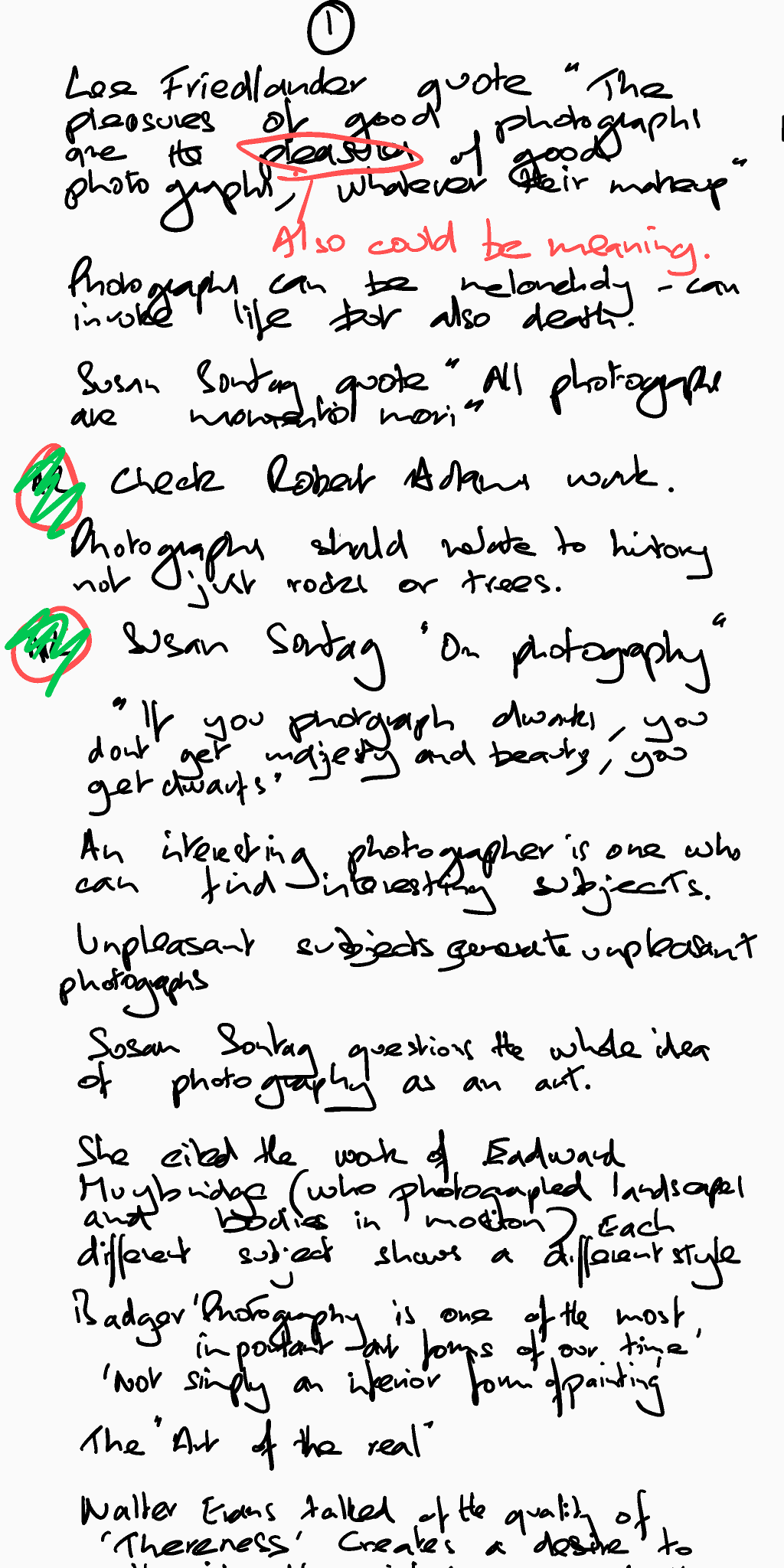

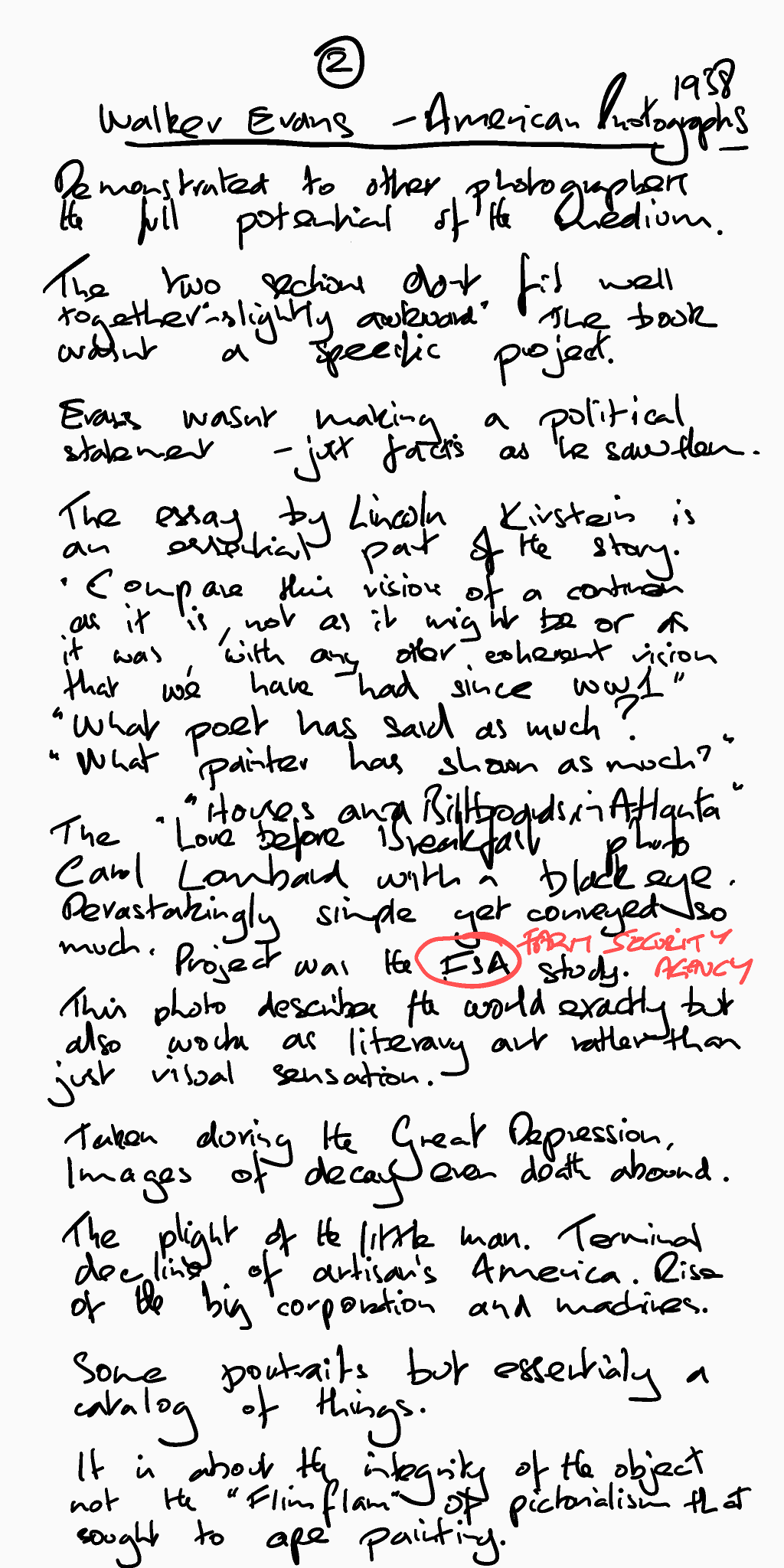

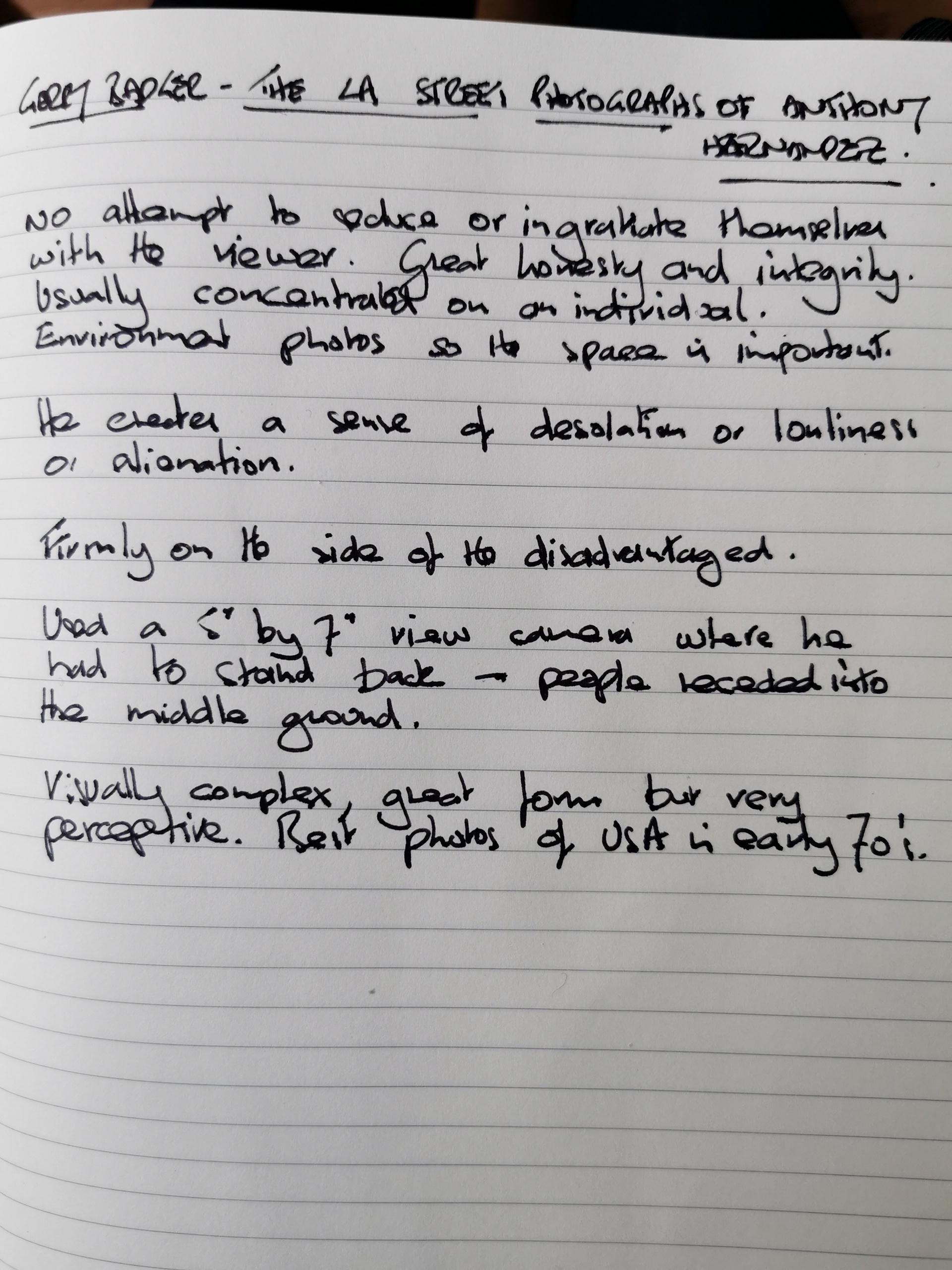

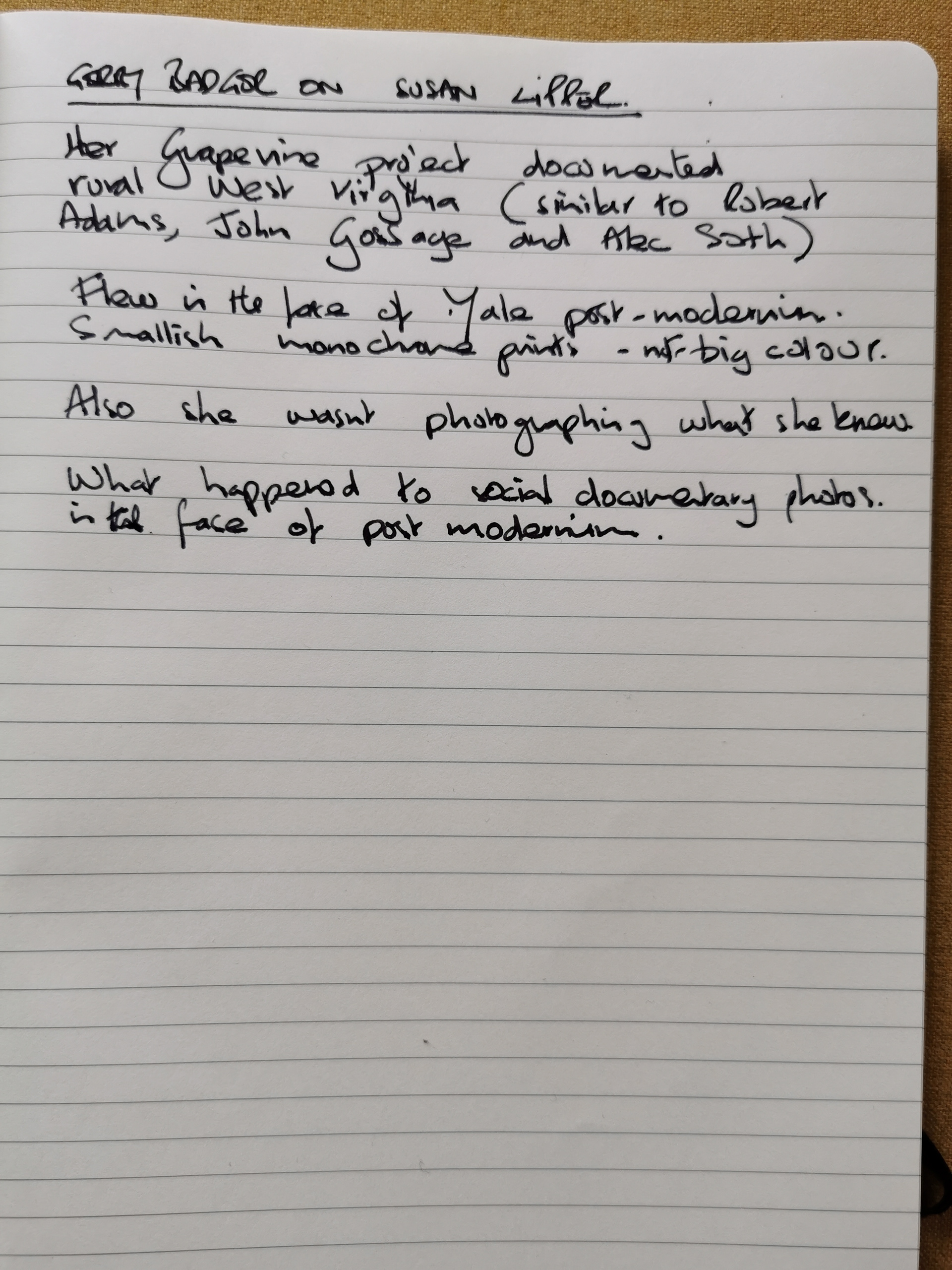

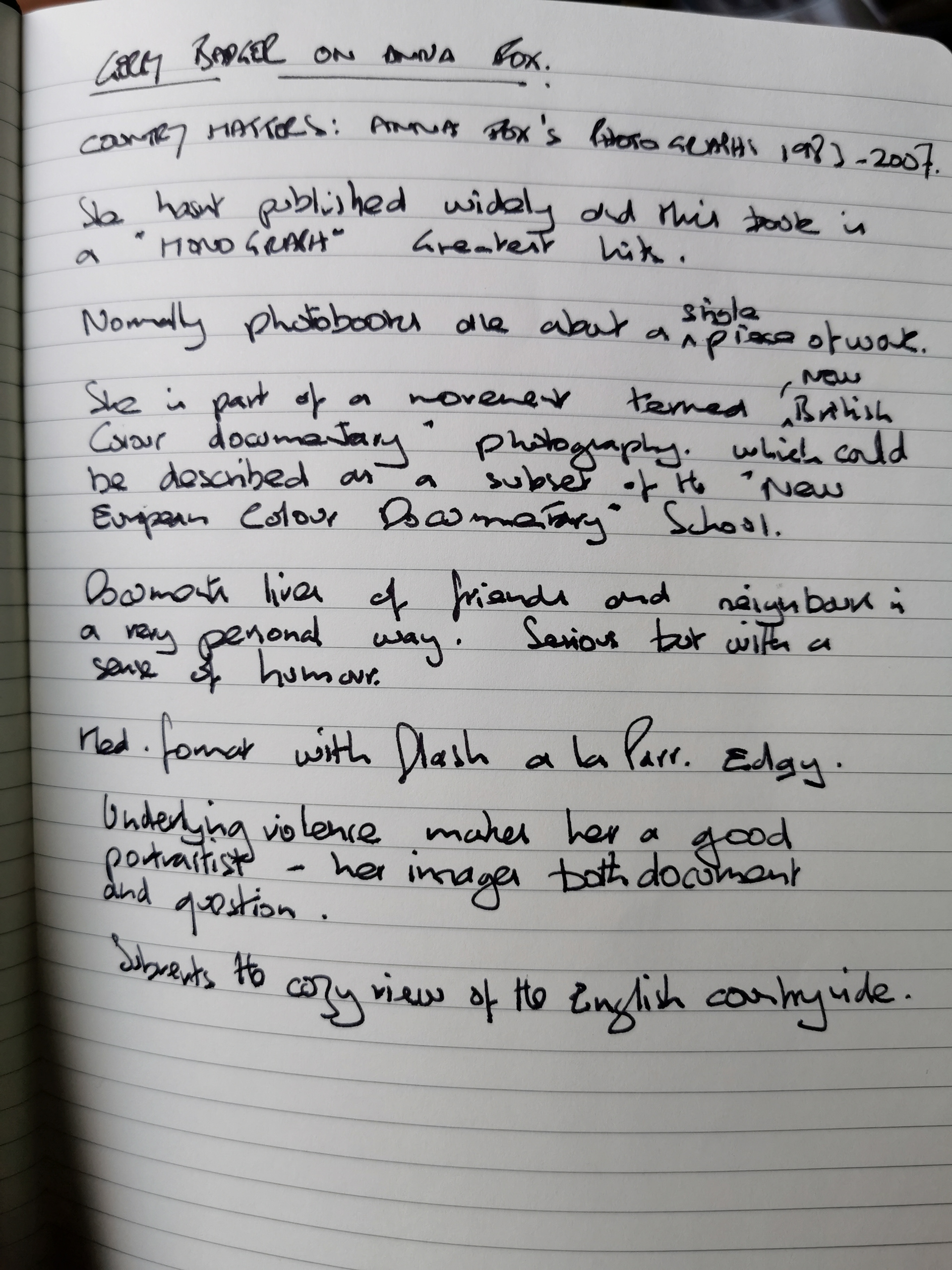

NOTES FROM READING