The master of the studio portrait whose dramatic lighting and commanding compositions revealed the inner character of the twentieth century's most consequential figures, creating iconic images that defined how the world saw its leaders, artists, and thinkers.

1908, Mardin, Ottoman Empire – 2002, Boston, Massachusetts — Armenian-Canadian

Yousuf Karsh was born on 23 December 1908 in Mardin, a city in the Armenian heartland of the Ottoman Empire, into a family that would soon be engulfed by one of the twentieth century's great catastrophes. During the Armenian Genocide, the young Karsh witnessed violence and deprivation that scarred him for life. In 1924, at the age of sixteen, his family sent him to safety in Canada, where he was taken in by his uncle, George Nakash, a portrait photographer in Sherbrooke, Quebec. It was in his uncle's studio that Karsh first encountered the camera and discovered his vocation. Recognising the boy's talent and determination, Nakash arranged for him to apprentice with John Garo, a distinguished portrait photographer in Boston who had studied painting and brought to his photographic portraits a painterly sensibility rooted in the traditions of Rembrandt and Velazquez.

Under Garo's tutelage, Karsh learned the craft of studio portraiture at its highest level: the precise control of artificial light, the careful arrangement of pose and gesture, the use of shadow to model form and reveal character. These lessons formed the technical foundation of his practice, but Karsh brought to them an emotional intensity and a psychological acuity that were entirely his own. He returned to Canada in 1932 and established a studio in Ottawa, the national capital, a location that would prove strategically advantageous. Through the patronage of Prime Minister Mackenzie King, who admired his work, Karsh gained access to the political and diplomatic elite who passed through Ottawa, and his reputation as a portraitist of unusual power began to grow.

The photograph that made Karsh world-famous came on 30 December 1941, when Winston Churchill visited Ottawa to address the Canadian Parliament shortly after the attack on Pearl Harbor. Karsh had been granted two minutes with Churchill after the speech. Churchill, cigar clamped in his teeth, was not inclined to cooperate. Karsh stepped forward and plucked the cigar from Churchill's mouth. The resulting expression — a scowl of magnificent belligerence, jaw set, fist clenched on the arm of the chair — became one of the most reproduced photographs in history. It appeared on the cover of Life magazine and came to embody the spirit of British defiance during the darkest days of the Second World War. The image made Karsh internationally famous overnight, and from that moment he was in demand as the portraitist of choice for the most powerful and accomplished people on earth.

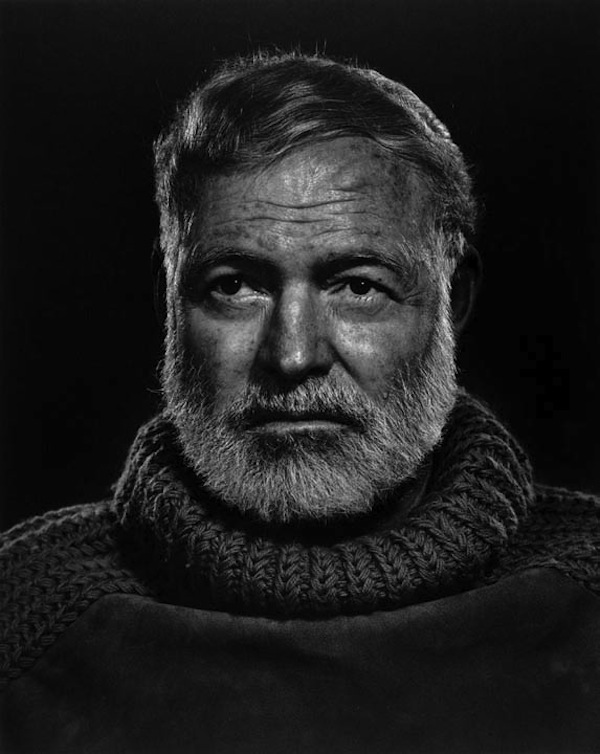

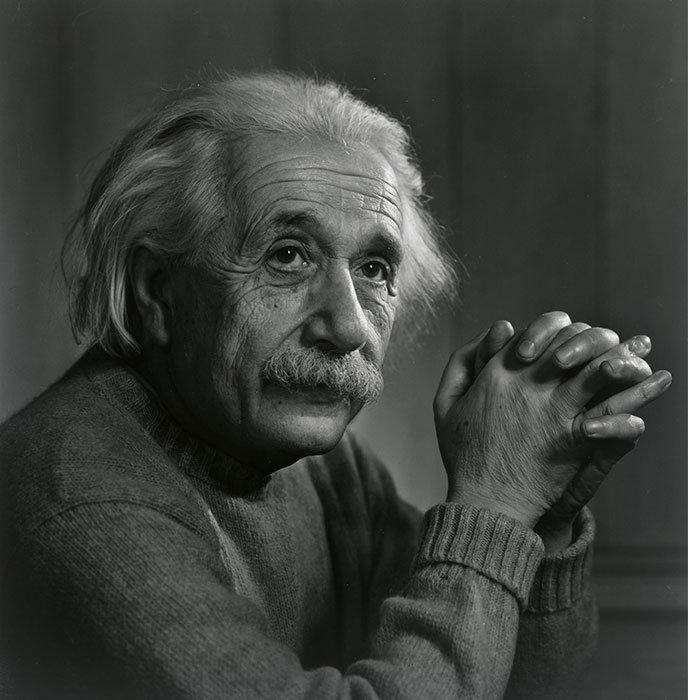

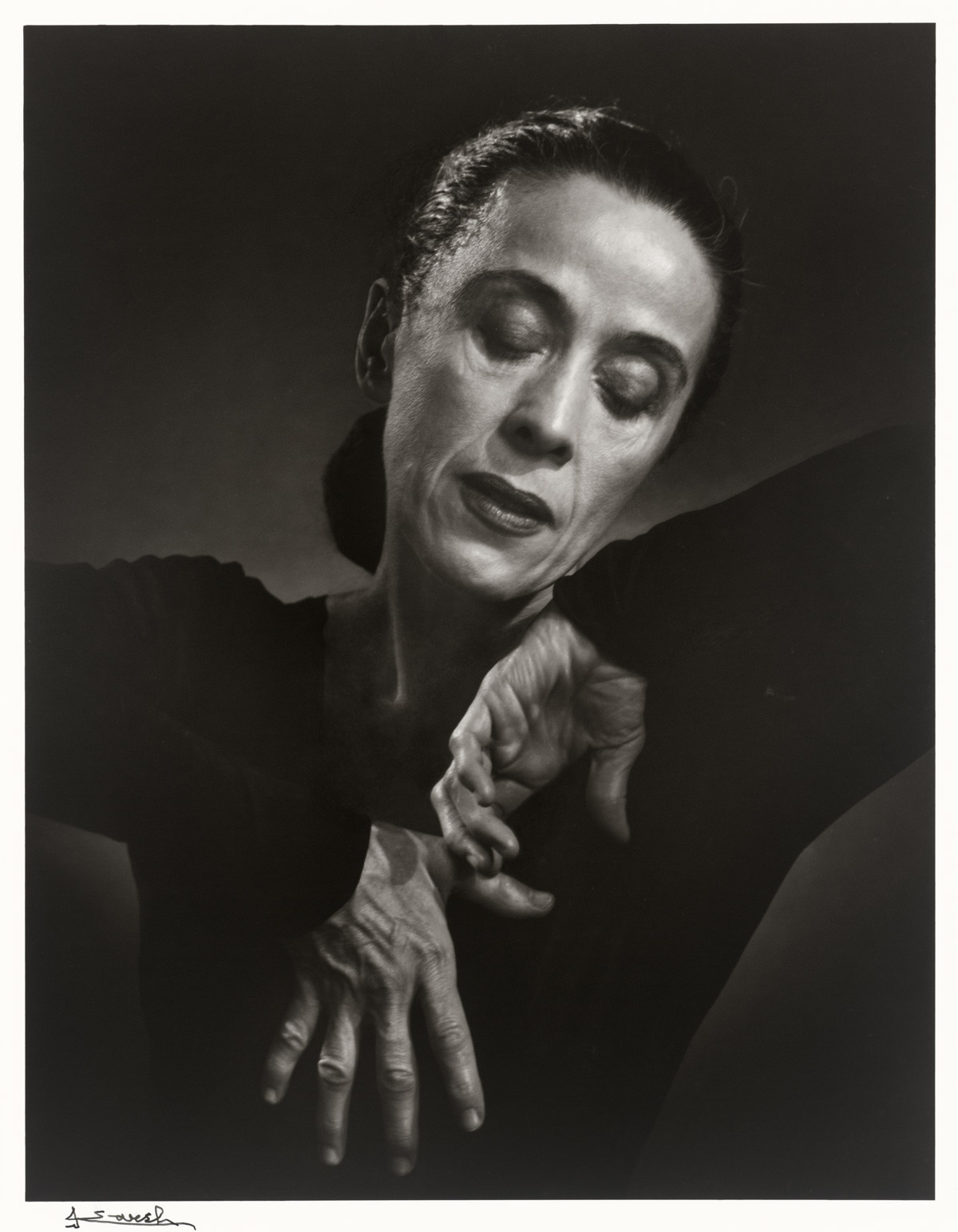

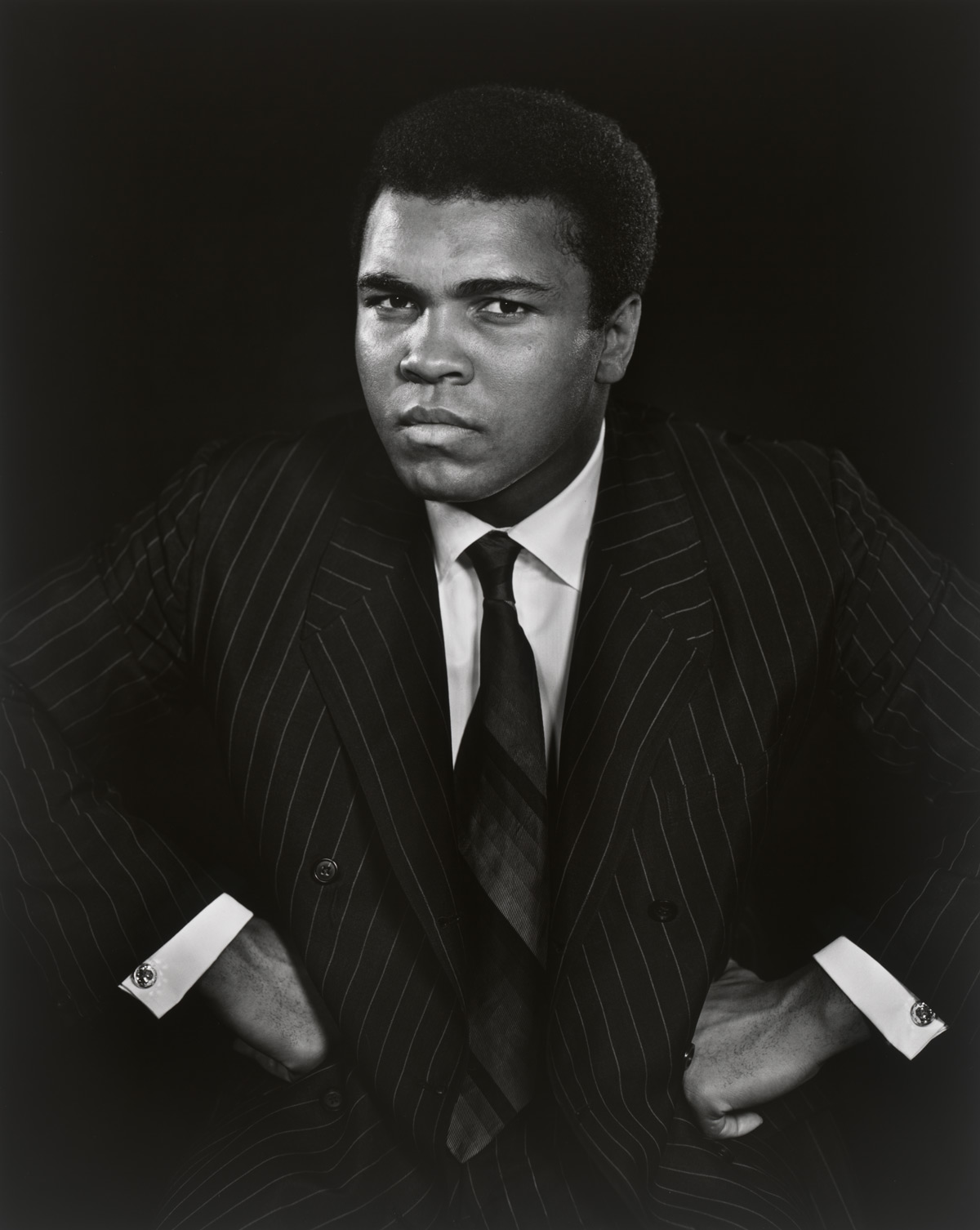

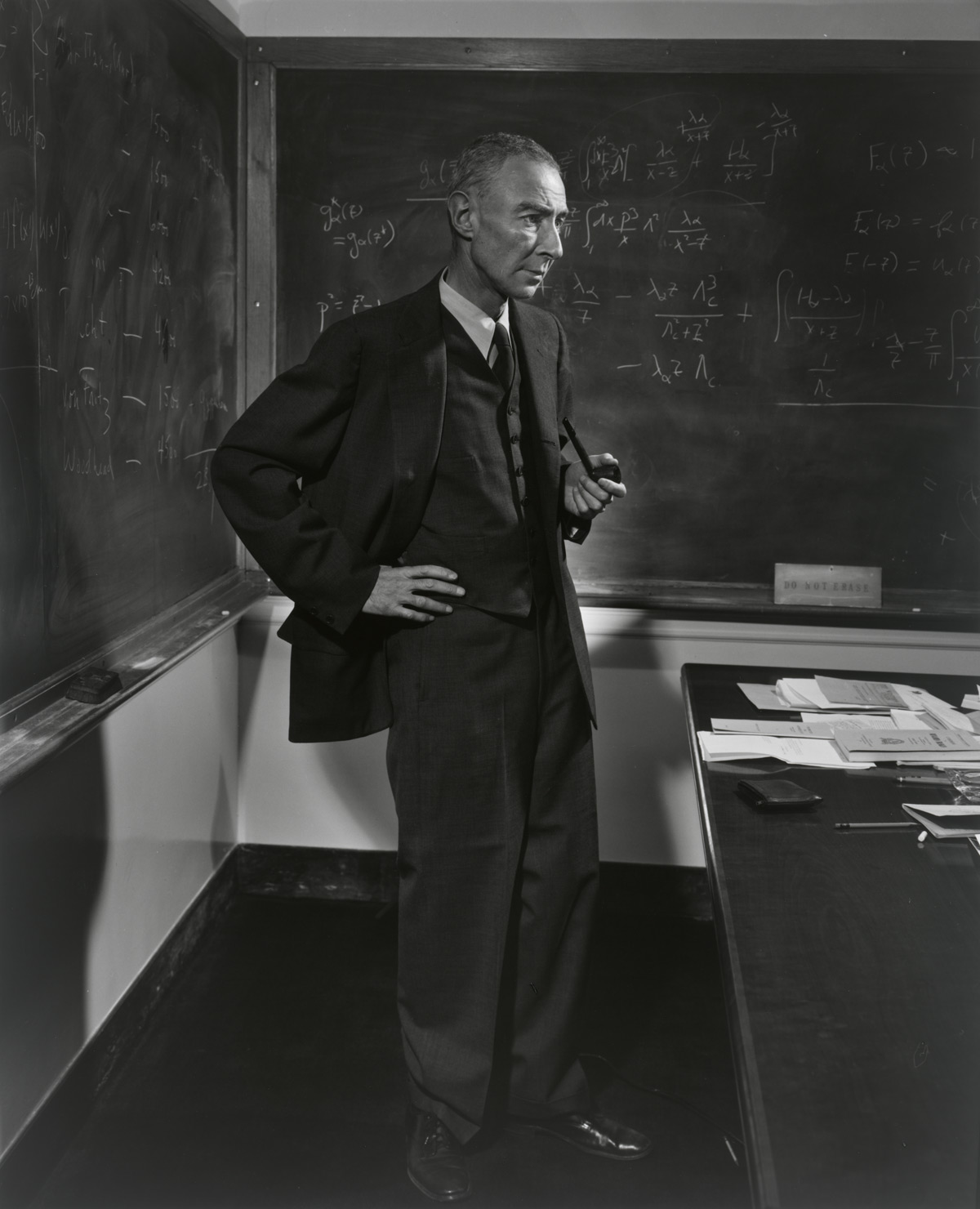

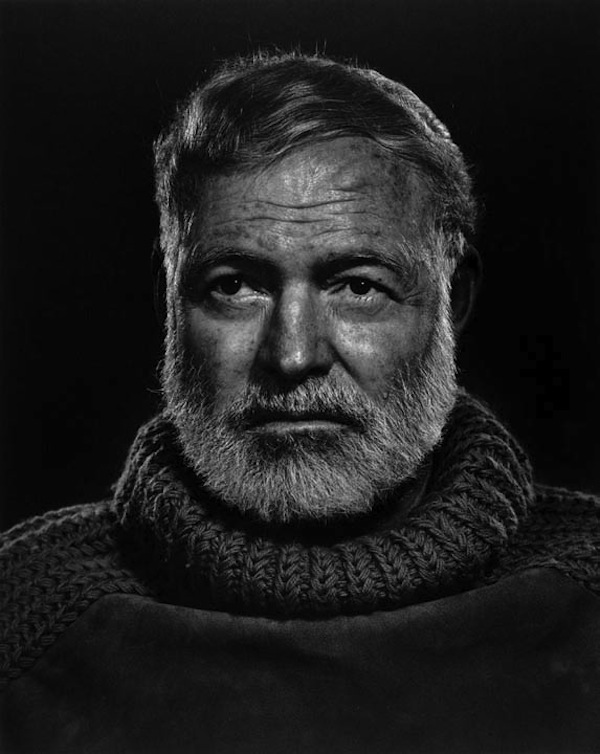

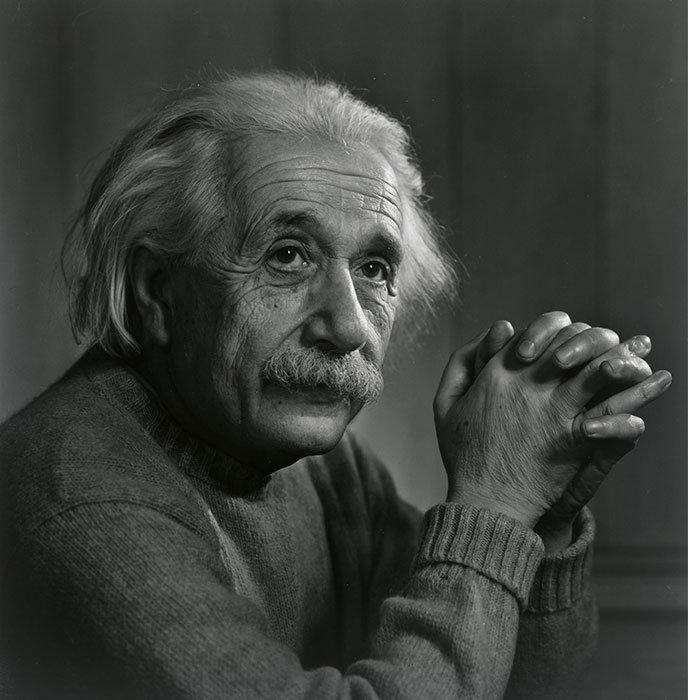

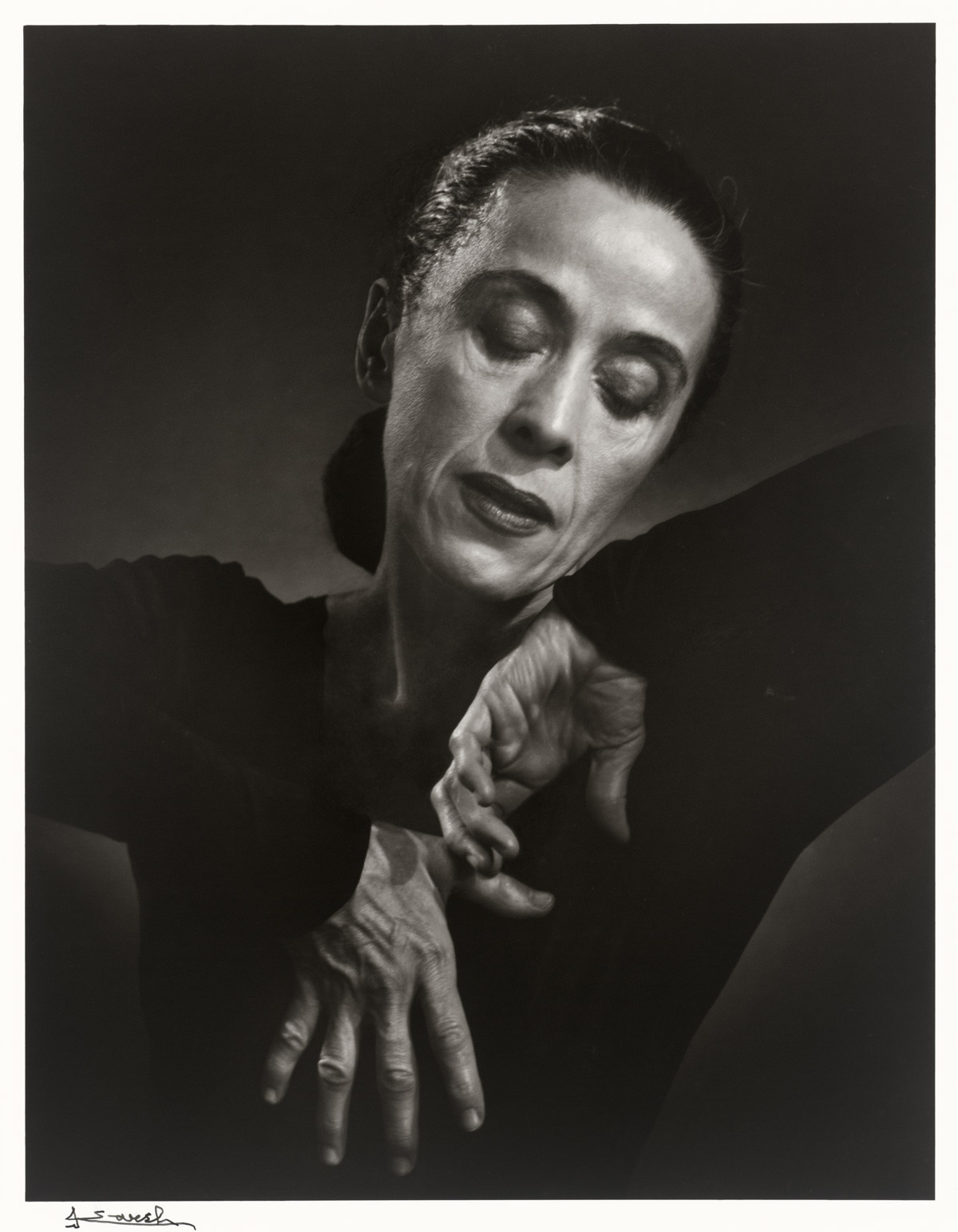

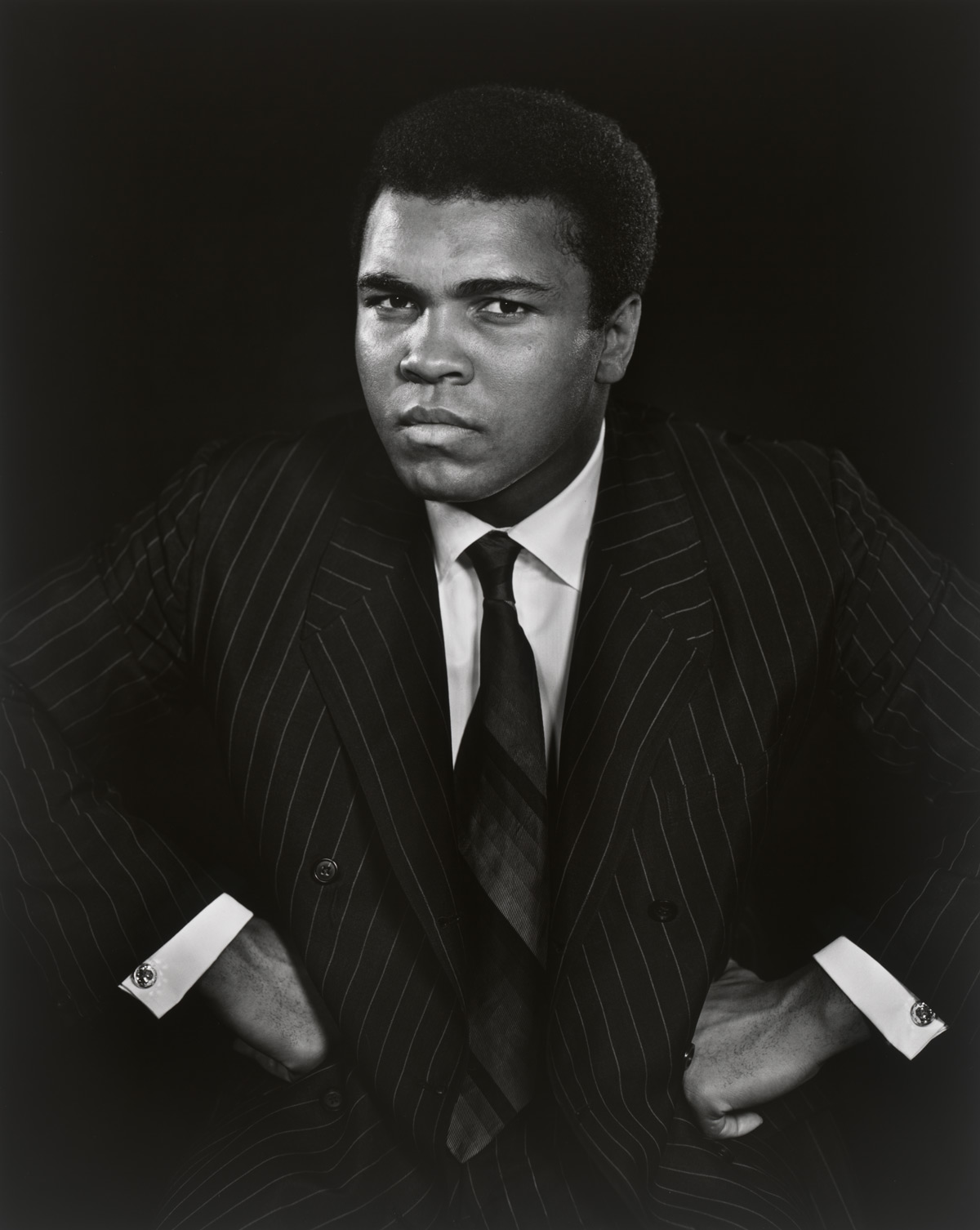

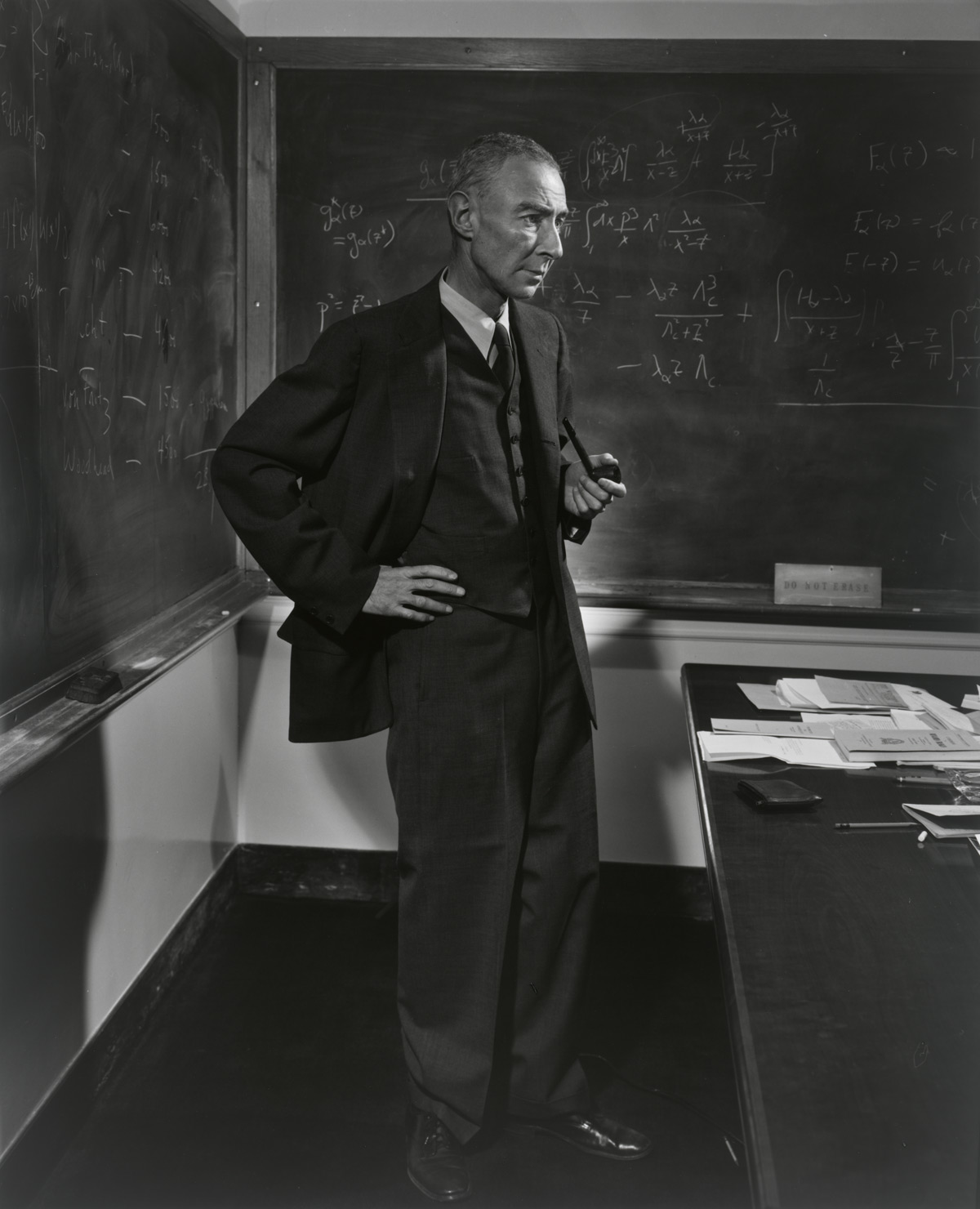

Over the next six decades, Karsh photographed virtually every major figure of the twentieth century. His subjects included presidents and prime ministers, kings and queens, scientists, writers, musicians, artists, and religious leaders. Albert Einstein, Pablo Picasso, Ernest Hemingway, Georgia O'Keeffe, Pablo Casals, Martin Luther King Jr., Audrey Hepburn, Muhammad Ali, Fidel Castro, Nelson Mandela — the list reads as a catalogue of twentieth-century eminence. In each case, Karsh sought to reveal what he called the inner strength of his subjects, using his mastery of light and composition to create images that were at once psychologically penetrating and formally magnificent.

Karsh's technique was rooted in the studio tradition, and he remained committed to controlled, carefully lit portraiture throughout his career, even as photography moved increasingly toward the candid, the spontaneous, and the ambient. His lighting was dramatic and sculptural, drawing on the chiaroscuro traditions of Old Master painting. He favoured strong directional light that modelled the planes of the face, carved the hands into expressive instruments, and isolated his subjects against dark or neutral backgrounds. The hands, in particular, were a Karsh signature: he believed that hands could reveal as much about a person's character as the face, and he devoted meticulous attention to their placement and illumination.

Critics of Karsh have sometimes argued that his approach was too theatrical, too flattering, too invested in the idea of greatness. There is truth in the observation that Karsh's portraits tend to ennoble their subjects, to present them as figures of consequence and dignity. But this was a conscious artistic choice, not a failure of perception. Karsh had survived genocide. He had witnessed the worst that human beings could do to one another, and his portraits can be understood as an affirmation of the opposite: a belief in human achievement, creativity, and moral courage. His camera sought the best in people, and his lighting, posing, and printing were all designed to bring that best into visible form.

Karsh's work was widely published in magazines including Life, Time, Newsweek, and Esquire, and he produced numerous books of collected portraits, including Faces of Destiny (1946), Portraits of Greatness (1959), and Karsh: A Sixty-Year Retrospective (1996). His photographs are held in the permanent collections of major institutions worldwide, including the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the National Portrait Gallery in London, and the National Gallery of Canada.

Yousuf Karsh retired from active photography in 1992 and donated his archive of more than 355,000 negatives to the Library and Archives Canada. He died in Boston on 13 July 2002, at the age of ninety-three. He left behind a body of work that constitutes the most comprehensive and accomplished photographic record of twentieth-century achievement. His portraits did not merely document the famous; they shaped how the world perceived them, creating definitive images that remain, for many of his subjects, the picture that comes to mind when one hears their name.

Within every man and woman a secret is hidden, and as a photographer it is my task to reveal it if I can. Yousuf Karsh

The portrait that made Karsh famous overnight, capturing Churchill's defiant scowl moments after Karsh plucked the cigar from his hand. It became one of the most reproduced photographs in history and an enduring symbol of wartime resolve.

A comprehensive collection of portraits spanning decades of Karsh's career, assembling world leaders, artists, scientists, and writers into a visual pantheon of twentieth-century achievement, each rendered with Karsh's signature dramatic lighting.

A recurring motif throughout Karsh's career, his meticulous attention to the hands of his subjects — from Casals's cellist's fingers to Hemingway's clenched fists — revealed character and vocation through gesture and form.

Born in Mardin, in the Armenian heartland of the Ottoman Empire. Witnesses the Armenian Genocide as a young child.

Arrives in Canada at age sixteen, taken in by his uncle George Nakash, a portrait photographer in Sherbrooke, Quebec.

Apprentices with John Garo in Boston, learning the traditions of painterly studio portraiture that will form the foundation of his practice.

Establishes his portrait studio in Ottawa, the Canadian capital, gaining access to political and diplomatic figures through the patronage of Prime Minister Mackenzie King.

Photographs Winston Churchill in Ottawa, producing the iconic portrait that appears on the cover of Life magazine and makes Karsh internationally famous.

Publishes Faces of Destiny, his first major book of collected portraits, establishing the format for a lifetime of publication.

Publishes Portraits of Greatness, a landmark collection that cements his reputation as the definitive portraitist of the twentieth century's most eminent figures.

Made a Companion of the Order of Canada, the nation's highest civilian honour, in recognition of his contribution to the arts.

Retires from active photography and donates his archive of over 355,000 negatives to Library and Archives Canada.

Dies in Boston on 13 July, aged ninety-three. His portraits remain the definitive images of many of the twentieth century's most important figures.

Interested in discussing photography, collaboration, or just want to say hello? I’d love to hear from you.

Contact →