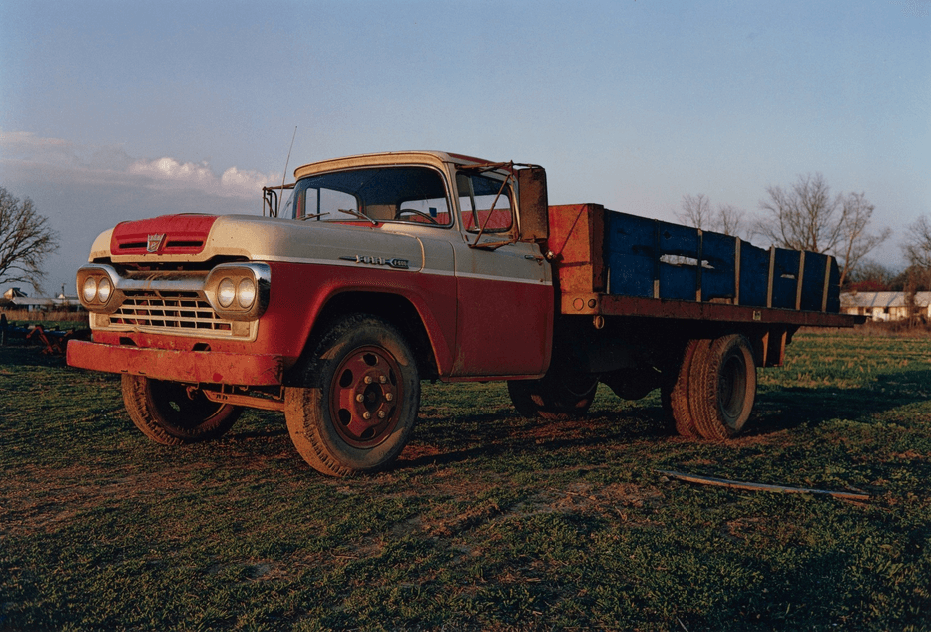

William Eggleston was born in Memphis, Tennessee, in 1939 and raised in Sumner, Mississippi, a small town in the heart of the cotton-growing Delta. His family belonged to the landed Southern aristocracy: his father was an engineer, his grandfather a prominent judge and plantation owner. Eggleston grew up in a world of slow afternoons, clapboard houses, red-dirt roads, and the particular light of the Deep South, a world that would furnish virtually all of the subjects he ever needed. From an early age he displayed a restless, eclectic curiosity, immersing himself in music, electronics, and drawing before discovering the medium that would become his life's work.

His formal education was scattered and deliberately incomplete. Eggleston enrolled at Vanderbilt University in Nashville in 1957, then transferred to Delta State College in Cleveland, Mississippi, and later to the University of Mississippi in Oxford, without ever taking a degree from any of them. It was during these years of drifting between institutions that he encountered the photographs of Henri Cartier-Bresson and, more decisively, Walker Evans. Cartier-Bresson's concept of the decisive moment captivated him, but Evans's cool, frontal attention to the vernacular architecture and material culture of the American South struck a deeper chord. Eggleston acquired a camera and began to photograph the world immediately around him with an intensity that belied the apparent casualness of his subjects.

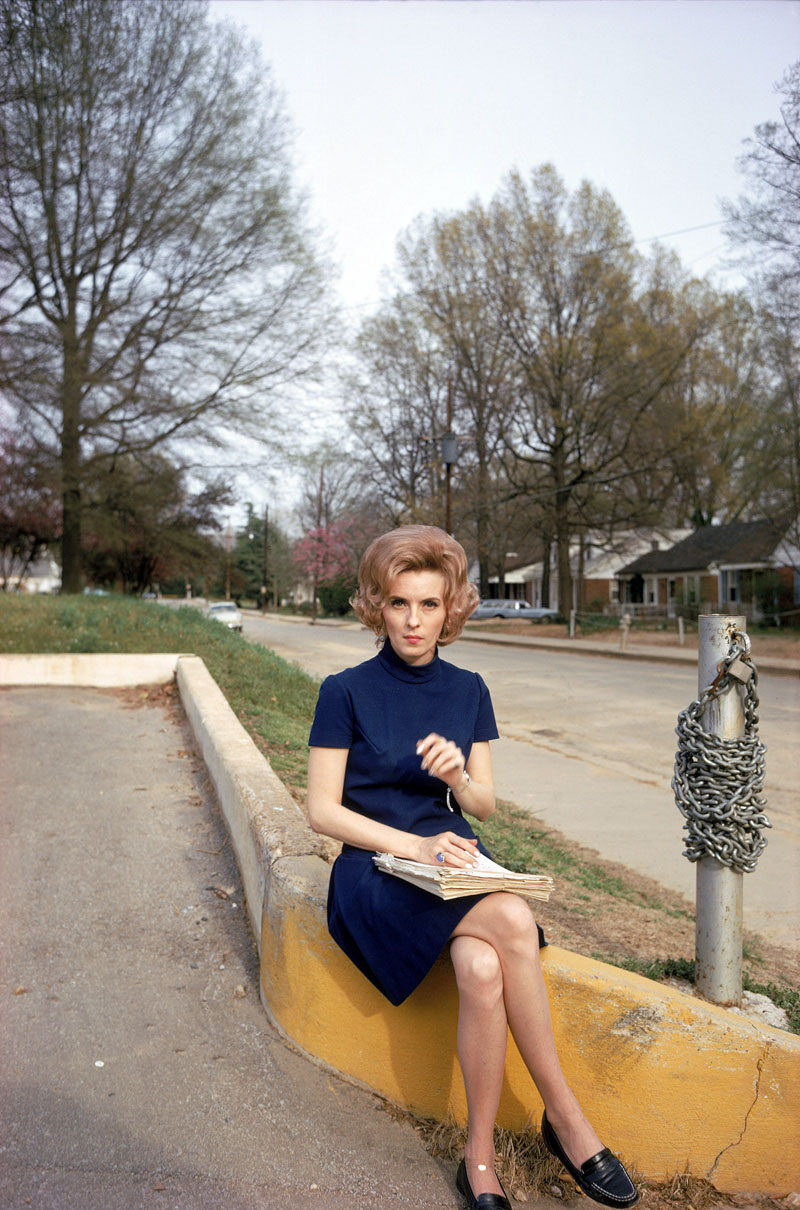

Through the early 1960s, Eggleston worked in black and white, producing competent images that nonetheless did not fully satisfy him. The pivotal moment in his development came when he made the decision to work exclusively in colour. At the time, this was a radical and even perverse choice. The art photography establishment, shaped by the monochrome tradition of Evans, Robert Frank, and the humanist documentary school, regarded colour as the province of commercial photography, advertising, and amateur snapshots. Colour was considered vulgar, unserious, and aesthetically uncontrollable. Eggleston saw it differently. He recognised that the world he inhabited was a world of colour — the electric blues of roadside signs, the burnt oranges of Southern sunsets, the lurid reds of motel interiors — and that to photograph it in black and white was to drain away something essential about the experience of seeing.

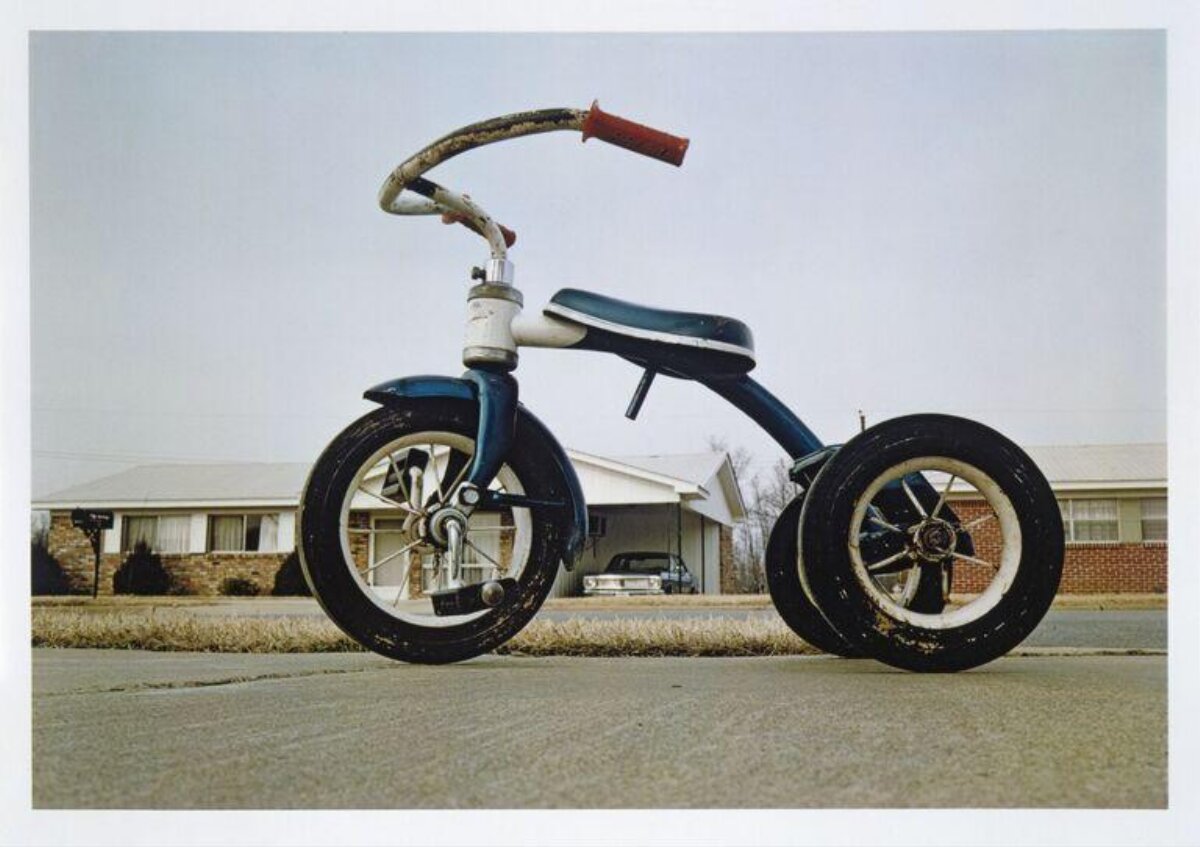

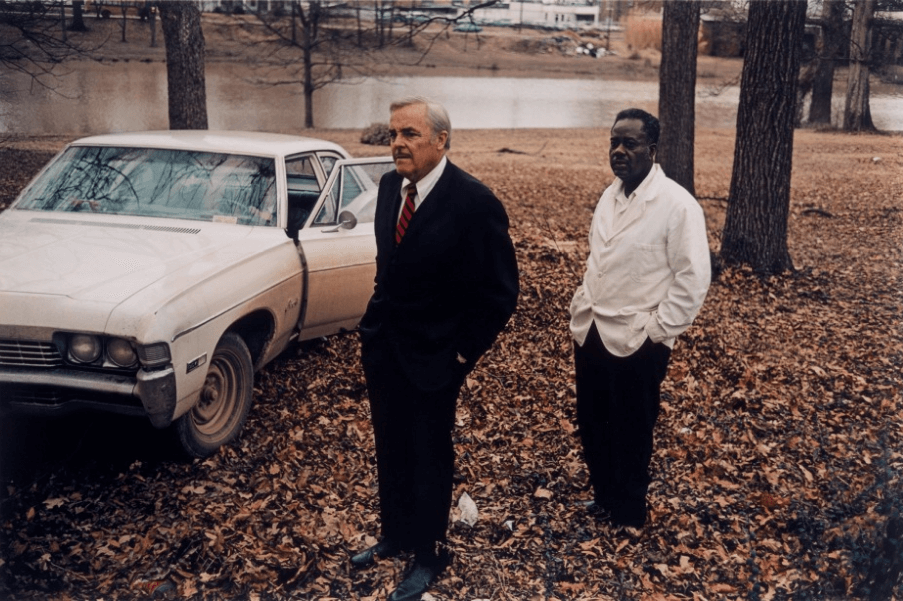

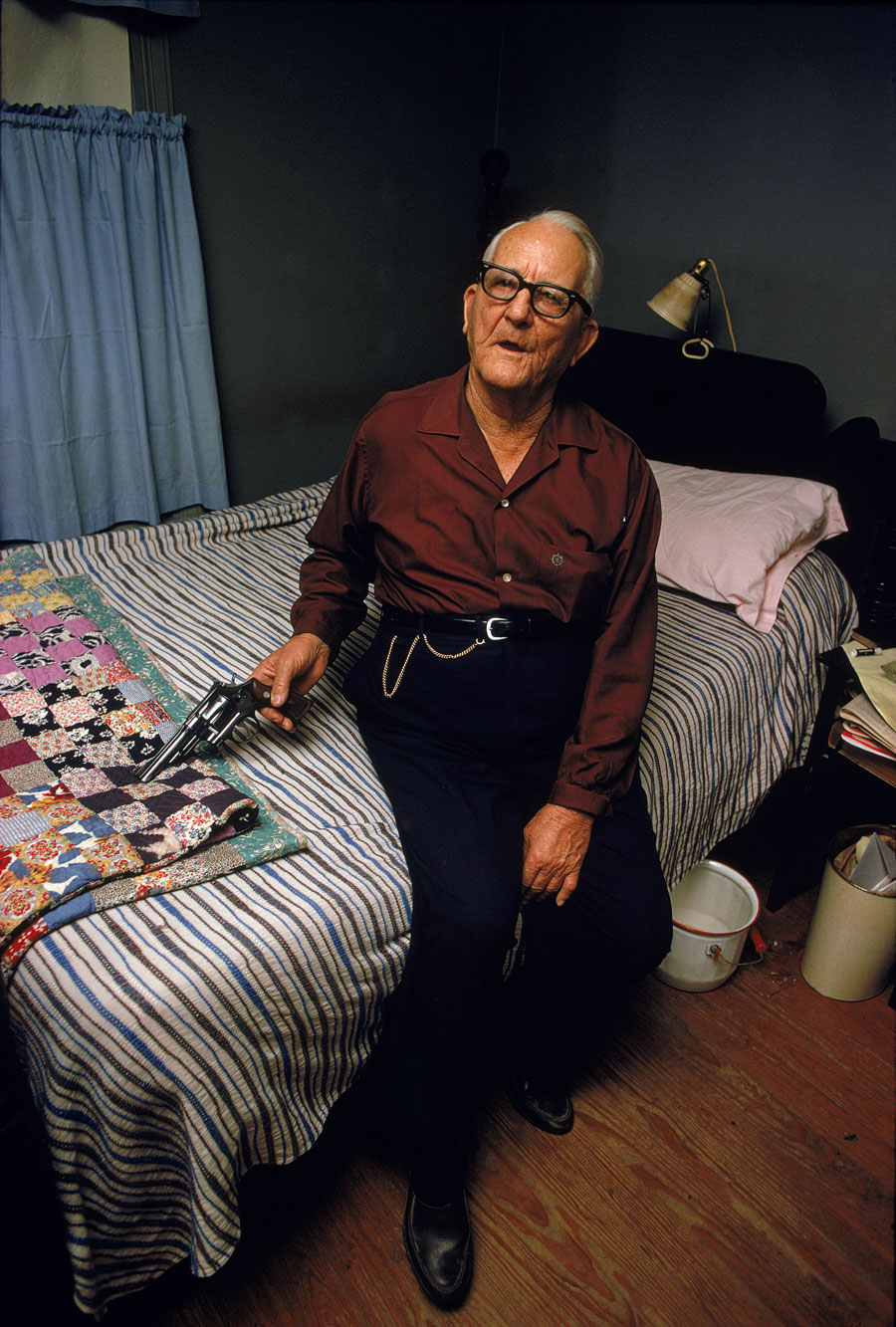

By the late 1960s and early 1970s, Eggleston had developed a mature visual language of extraordinary originality. He photographed tricycles on suburban pavements, ceiling tiles in rented rooms, grocery boys pushing carts across parking lots, the interiors of ovens, glasses of liquor on airplane tray tables, and the vast, flat landscapes of the Mississippi Delta. He approached every subject with what he would later call a democratic attitude: no subject was inherently more worthy of attention than any other. A shoelace deserved the same quality of seeing as a cathedral. This radical levelling of the visual hierarchy was deeply unsettling to critics who expected photographs to announce their importance through their subjects.

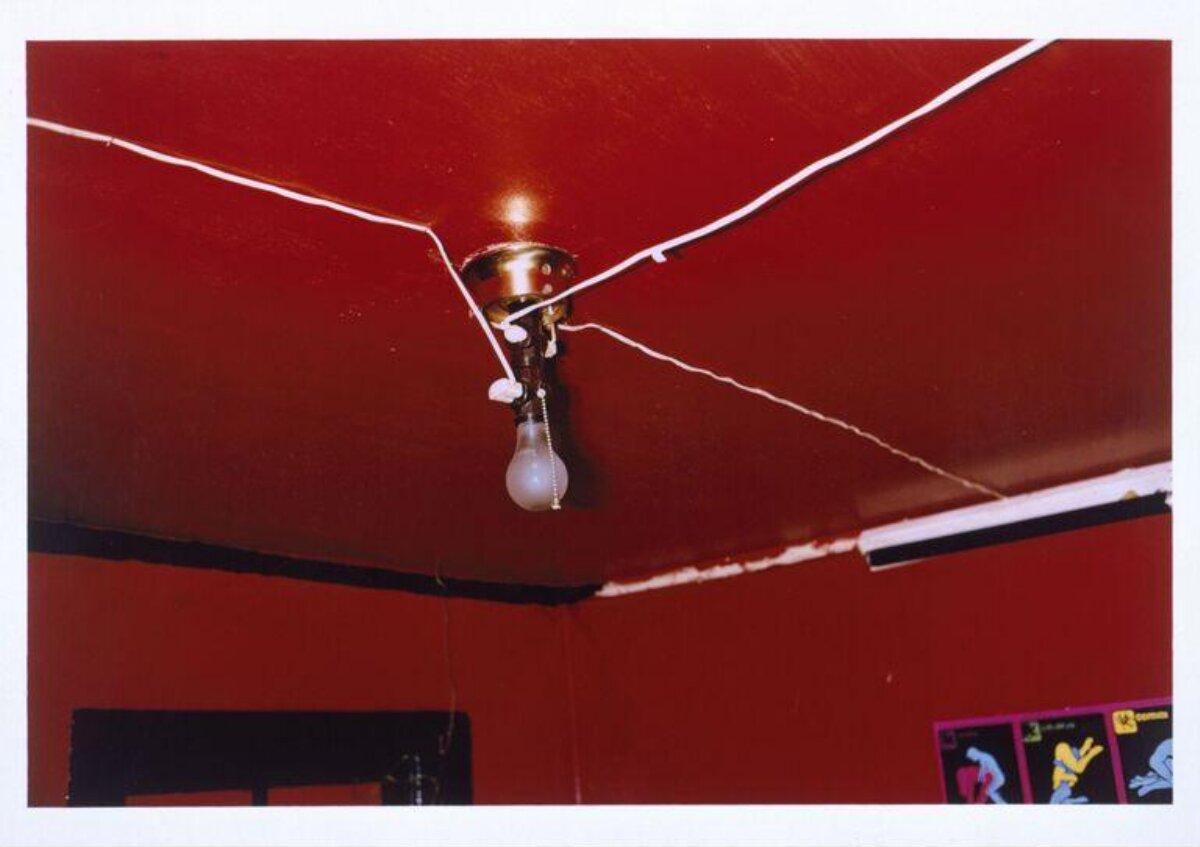

In 1973, Eggleston began working with the dye-transfer printing process, a commercial technique originally developed by Kodak for advertising imagery. The process was expensive, painstaking, and technically demanding, but it produced prints of astonishing colour saturation and luminosity. In Eggleston's hands, the dye-transfer print transformed ordinary scenes into something approaching the hallucinatory. His image of a red ceiling in Greenwood, Mississippi — a simple room with a bare lightbulb and blood-red walls — became, through the dye-transfer process, one of the most famous and discussed photographs of the twentieth century, an image that vibrates with an almost unbearable intensity of colour and feeling.

The watershed moment in Eggleston's career came in 1976, when John Szarkowski, the legendary director of photography at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, mounted William Eggleston's Guide, the first one-person exhibition of colour photographs in the museum's history. Szarkowski had championed Eggleston's work since 1967, recognising in it a new way of seeing that extended the documentary tradition into uncharted territory. The exhibition and its accompanying catalogue were met with fierce hostility from much of the critical establishment. The New York Times dismissed the photographs as banal and boring. Other critics found them technically crude or thematically empty. Yet within a few years, the tide had turned. Eggleston's show is now recognised as one of the most consequential exhibitions in the history of photography, the moment at which colour was admitted to the fine-art canon.

The influence of Eggleston's vision on subsequent generations of photographers has been immense and pervasive. Stephen Shore, working independently but along parallel lines, brought a complementary large-format precision to colour photography in the same period. Joel Sternfeld extended the colour tradition into the landscape of American public space. Martin Parr adopted a saturated, flash-lit palette to chronicle British consumer culture. The entire movement that came to be known as New Color Photography is unthinkable without Eggleston's pioneering work. His influence extends beyond photography into cinema, fashion, music, and graphic design; filmmakers such as David Lynch, Sofia Coppola, and Wim Wenders have all cited his images as formative visual touchstones.

Now in his mid-eighties, Eggleston continues to photograph and to exhibit his work around the world. Major retrospectives have been mounted at the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Fondation Cartier in Paris, and the National Portrait Gallery in London. He has received the Outstanding Contribution to Photography award from the Royal Photographic Society and is universally acknowledged as one of the most important and influential artists of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. His achievement is at once simple and profound: he taught us that the ordinary world, seen with sufficient attention and love, is inexhaustible in its beauty, strangeness, and meaning.