Usher Fellig was born in 1899 in Lemberg, then part of Austria-Hungary and now the Ukrainian city of Lviv. His family moved briefly to Złoczew before emigrating to the United States in 1909, settling on New York's Lower East Side amid the teeming immigrant tenements that would later become his photographic territory. The family was poor, his father a pushcart peddler, and Usher left home at fourteen to fend for himself. He worked a string of odd jobs — candy seller, dishwasher, itinerant tintype photographer — before finding his way into the newspaper industry, where his relentless energy and instinct for the dramatic would make him the most famous news photographer in America.

Through the 1920s, Fellig worked as a darkroom technician at Acme Newspictures (later United Press International Photos), developing and printing the crime, fire, and accident photographs that filled the city's tabloids. The work was anonymous but formative: night after night he handled images of the city's violence and spectacle, absorbing the visual grammar of the tabloid front page. By the early 1930s he had begun shooting his own pictures, and by 1935 he had left the darkroom entirely to become a freelance news photographer, selling his prints to the New York Post, the Daily News, PM, and the wire services.

What set Fellig apart from every other press photographer in the city was his extraordinary proximity to the action. In 1938 he became the only newspaper photographer in New York with a permit to install a police-band shortwave radio in his car, a battered Chevrolet that doubled as his office, darkroom, and bedroom. He kept the car stocked with flashbulbs, film holders, a change of clothes, and cigars, parked near Manhattan Police Headquarters on Centre Street, and listened to the radio crackle through the night. When a call came in — a shooting on the Bowery, a tenement fire in Harlem, a gangland execution on the Lower East Side — he was often the first to arrive, sometimes before the police themselves.

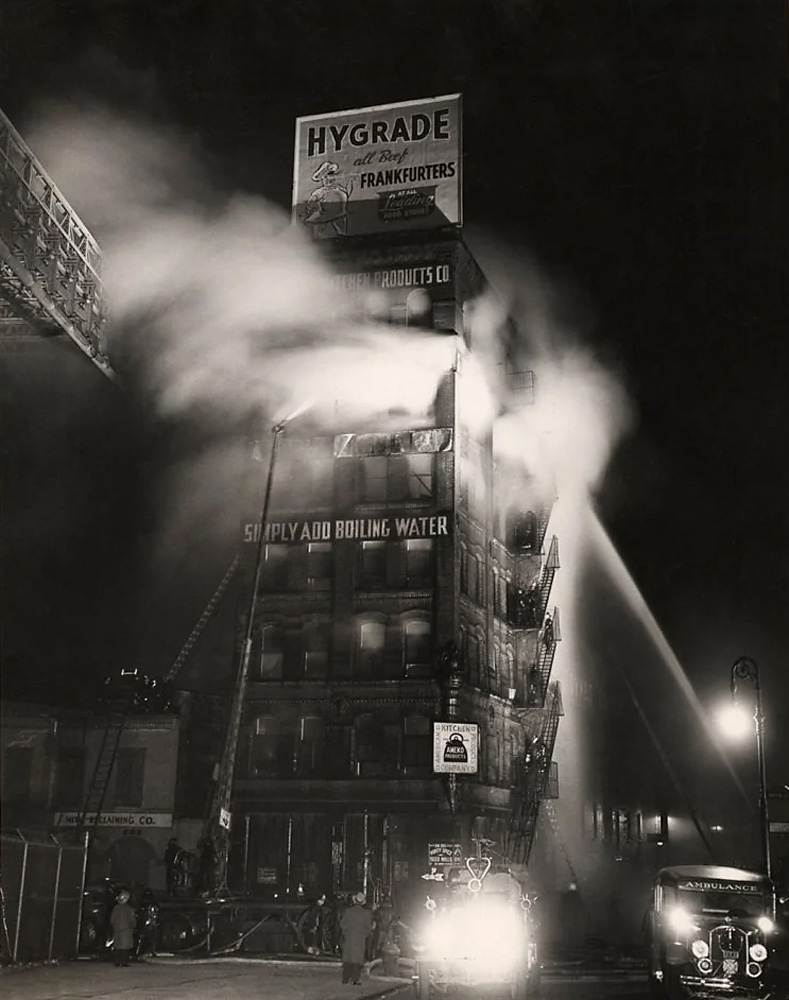

His equipment was as blunt as his sensibility. He shot almost exclusively with a 4×5 Speed Graphic camera fitted with a bare flashbulb, the standard press camera of the era. The direct flash, fired at close range, produced the signature look of his photographs: harsh, flat, merciless light that bleached his subjects against a pitch-black background, eliminating depth and nuance in favour of stark graphic impact. There was no subtlety in a Weegee photograph and no pretence of objectivity. His pictures hit you like a tabloid headline, and that was exactly the point.

The name Weegee itself was part of the legend. He claimed it derived from the Ouija board — a reference to his uncanny ability to predict where news would happen next. In truth, the ability owed more to the police radio, a network of tipsters, and sheer persistence than to any supernatural gift. But the self-mythologising was essential to his persona. Weegee understood that in the tabloid world, the photographer was as much a character as the subjects he photographed. He cultivated a rumpled, cigar-chomping image, stamped his prints with the credit “Credit Photo by Weegee the Famous”, and played the role of the street-smart wise guy with evident relish.

In 1945 he published Naked City, a collection of his crime scenes, fires, street life, and tenement dramas that became a bestseller and established him as a public figure beyond the newspaper world. The book’s title — later borrowed for the classic 1948 film noir produced by Mark Hellinger — captured the essence of his vision: New York stripped bare, its glamour peeled back to reveal the violence, poverty, grief, and dark comedy that pulsed beneath the surface. A follow-up volume, Weegee’s People (1946), expanded the portrait to include the city’s citizens at rest and play, from Coney Island bathers packed flank to flank on the sand to movie audiences weeping in the dark of a Times Square cinema.

By the late 1940s, Weegee’s restless energy had carried him away from the news beat. He moved to Hollywood in 1947, working as a bit-part actor and technical consultant on film sets while experimenting with a new form of photography: distortion images created with prisms, kaleidoscopic lenses, and plastic sheeting placed over his lens. He turned these techniques on celebrities, politicians, and cultural icons, producing grotesque, funhouse-mirror portraits of figures like Marilyn Monroe, Salvador Dalí, and Dwight D. Eisenhower. The distortion work was playful and subversive, a logical extension of the tabloid sensibility that had always seen the world as slightly warped.

Weegee returned to New York in the late 1950s, a somewhat diminished figure whose moment as a press photographer had passed but whose legend continued to grow. He died in 1968 at the age of sixty-nine. His influence, however, proved enduring. The raw, confrontational, flash-lit aesthetic he pioneered became the foundation of an entire tradition of street and documentary photography. Diane Arbus acknowledged his impact on her own unflinching portraiture. Bruce Gilden adopted and intensified his in-your-face flash technique. The tabloid photography tradition that Weegee embodied — immediate, visceral, unapologetic — remains a vital current in photographic practice, a reminder that the camera’s power to shock and to witness is inseparable from its power to tell the truth.