Walker Evans was born in St. Louis, Missouri, in 1903, the son of an advertising director whose restless ambitions kept the family moving through the Midwest. He grew up in suburban Chicago and Toledo, Ohio, attending a series of preparatory schools before enrolling at Williams College in Massachusetts. He was a voracious reader but a restless student, drawn more to literature than to any fixed course of study. After a year at Williams he dropped out, and in 1926 he sailed to Paris, intent on becoming a writer. He spent a year absorbing Flaubert, Baudelaire, and the literary culture of the Left Bank, and it was during this period that he first encountered the photographs of Eugène Atget — those quiet, meticulous records of Parisian shopfronts, stairways, and empty streets that would leave an indelible mark on his own developing sensibility.

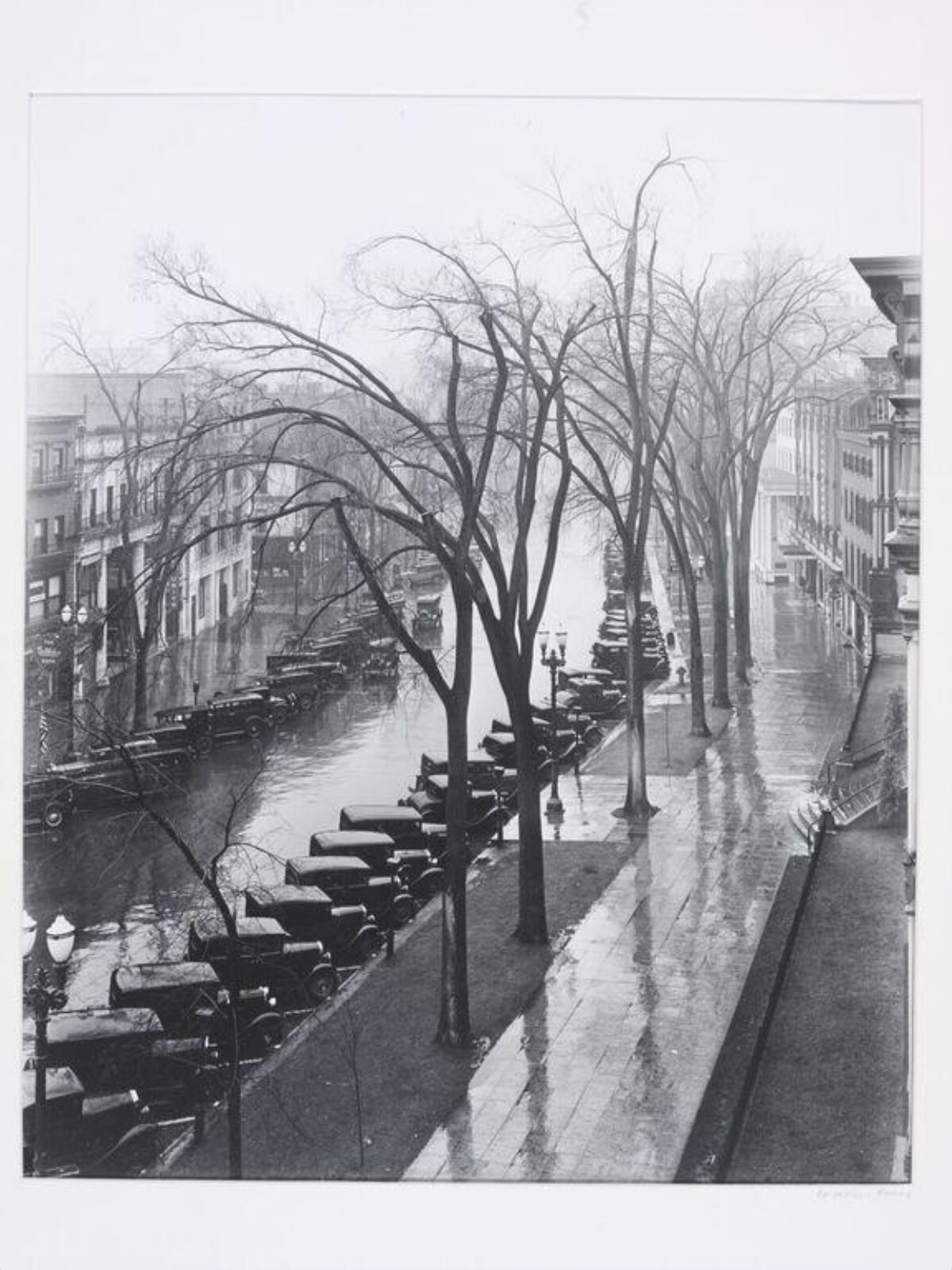

Returning to New York in 1927, Evans abandoned the ambition to write and turned instead to the camera. His literary formation, however, never left him. What he brought to photography was a writer's instinct for precision, for the weight and placement of every element within the frame, and above all for the distinction between sentiment and observation. He admired Flaubert's doctrine of the impersonal narrator, the author who refuses to intrude upon the scene, and he pursued its photographic equivalent with a discipline that bordered on austerity. His early work in New York — architectural studies, street signs, anonymous facades — already displayed the frontality, the deliberate plainness, and the refusal of drama that would become his signature.

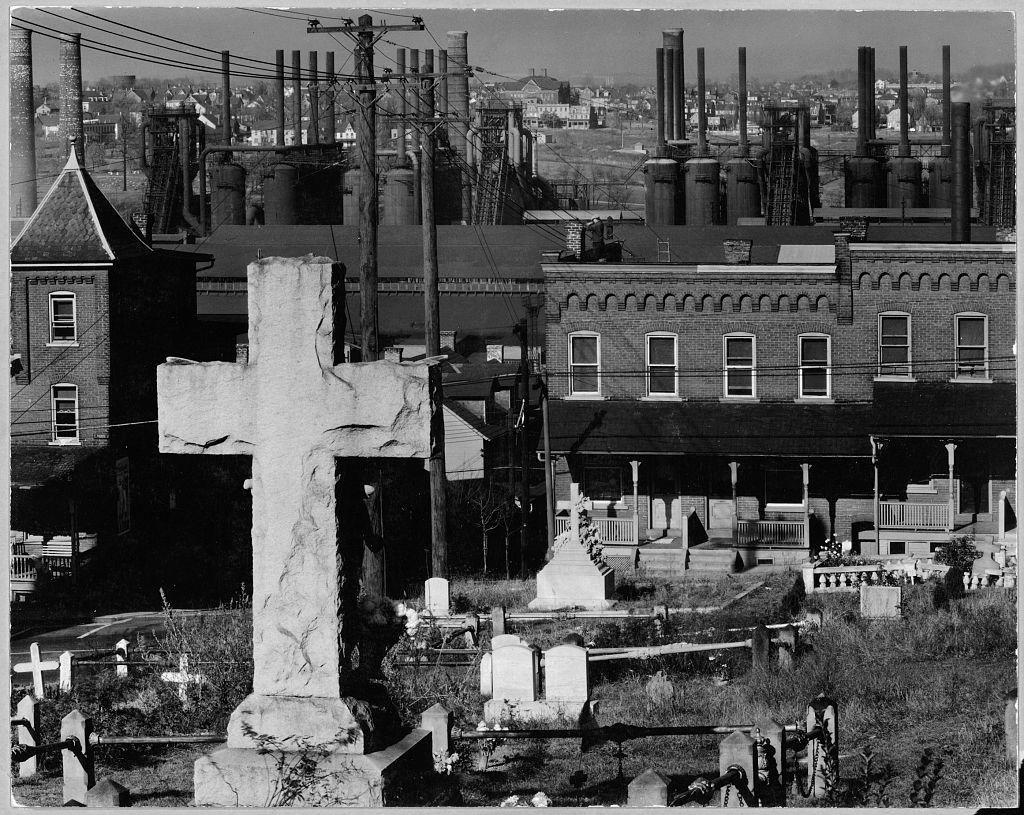

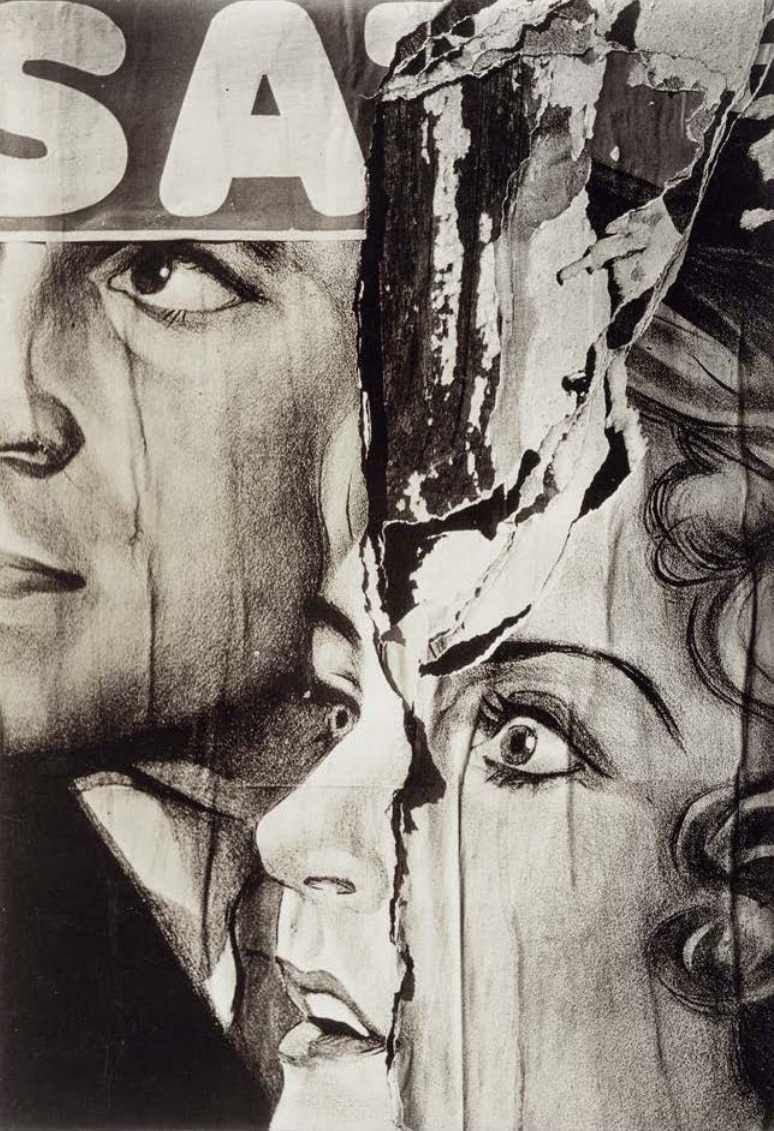

In 1933, Evans was given his first solo exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, organised by Lincoln Kirstein, the cultural impresario who recognised in Evans's work a new and rigorous way of seeing America. Two years later, Evans joined the Farm Security Administration, the New Deal agency that dispatched photographers across the country to document the conditions of rural poverty during the Great Depression. Between 1935 and 1937, Evans travelled through the American South, producing an extraordinary body of images: clapboard churches, roadside advertisements, sharecroppers' cabins, small-town main streets, and the weathered faces of people enduring hardship with a dignity that his camera recorded without embellishment or pity.

The FSA work established Evans as the foremost documentary photographer of his generation, but he was uneasy with the label. He drew a careful distinction between what he called the documentary style and documentary photography proper. The latter, he argued, served an agenda — social reform, political persuasion, journalistic reportage. The former borrowed the aesthetic of the document — its directness, its apparent objectivity, its refusal of artifice — but placed it in the service of art. Evans wanted his photographs to possess the authority of evidence without the burden of argument. It was a subtle but consequential distinction, and it became the philosophical foundation on which much of late twentieth-century art photography would be built.

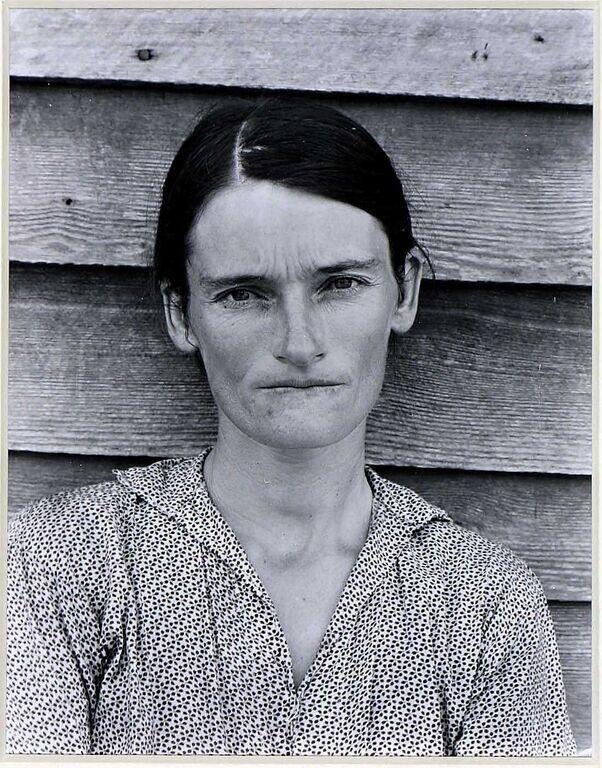

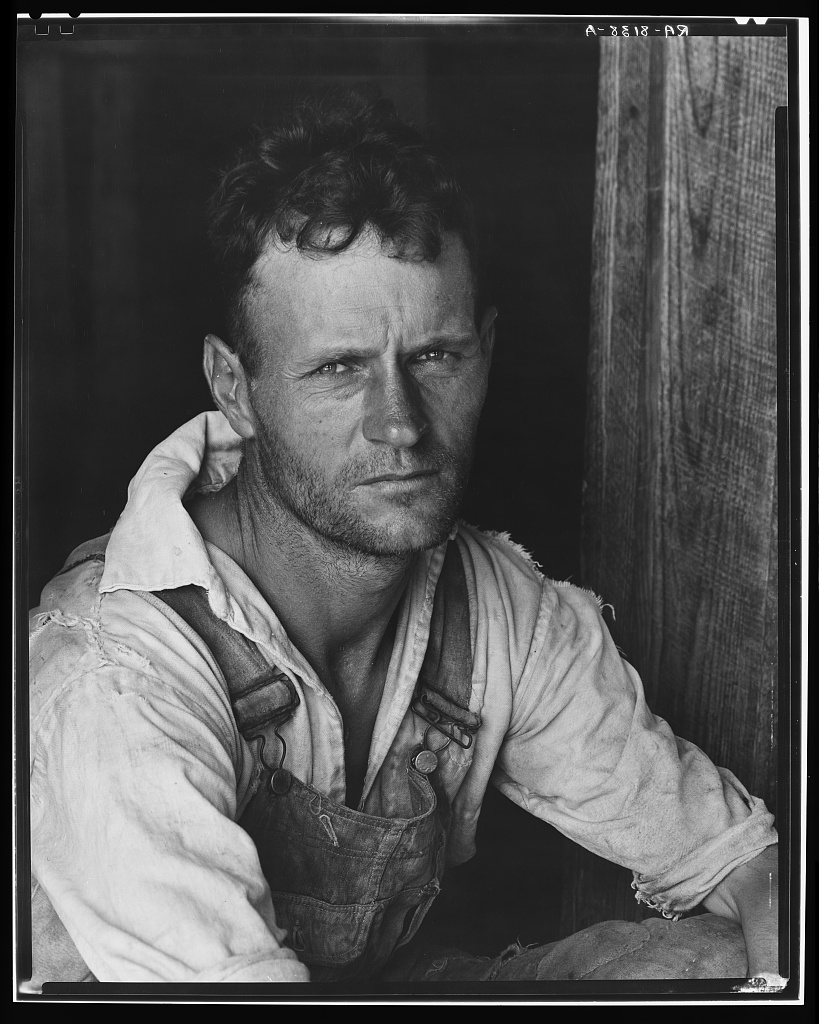

In the summer of 1936, Evans and the writer James Agee travelled to Hale County, Alabama, on assignment for Fortune magazine, to document the lives of three white sharecropper families. They spent several weeks living among the Burroughs, Fields, and Tingle families, Evans photographing their homes, possessions, and faces with his characteristic rigour while Agee wrote with feverish intensity. Fortune rejected the resulting article as too long and too unconventional. The material eventually became Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, published in 1941 to poor sales and mixed reviews. It was only in the 1960s that the book was recognised as one of the great American works of the twentieth century, a collaboration in which Evans's austere, frontal portraits and Agee's impassioned prose together achieved something neither could have accomplished alone.

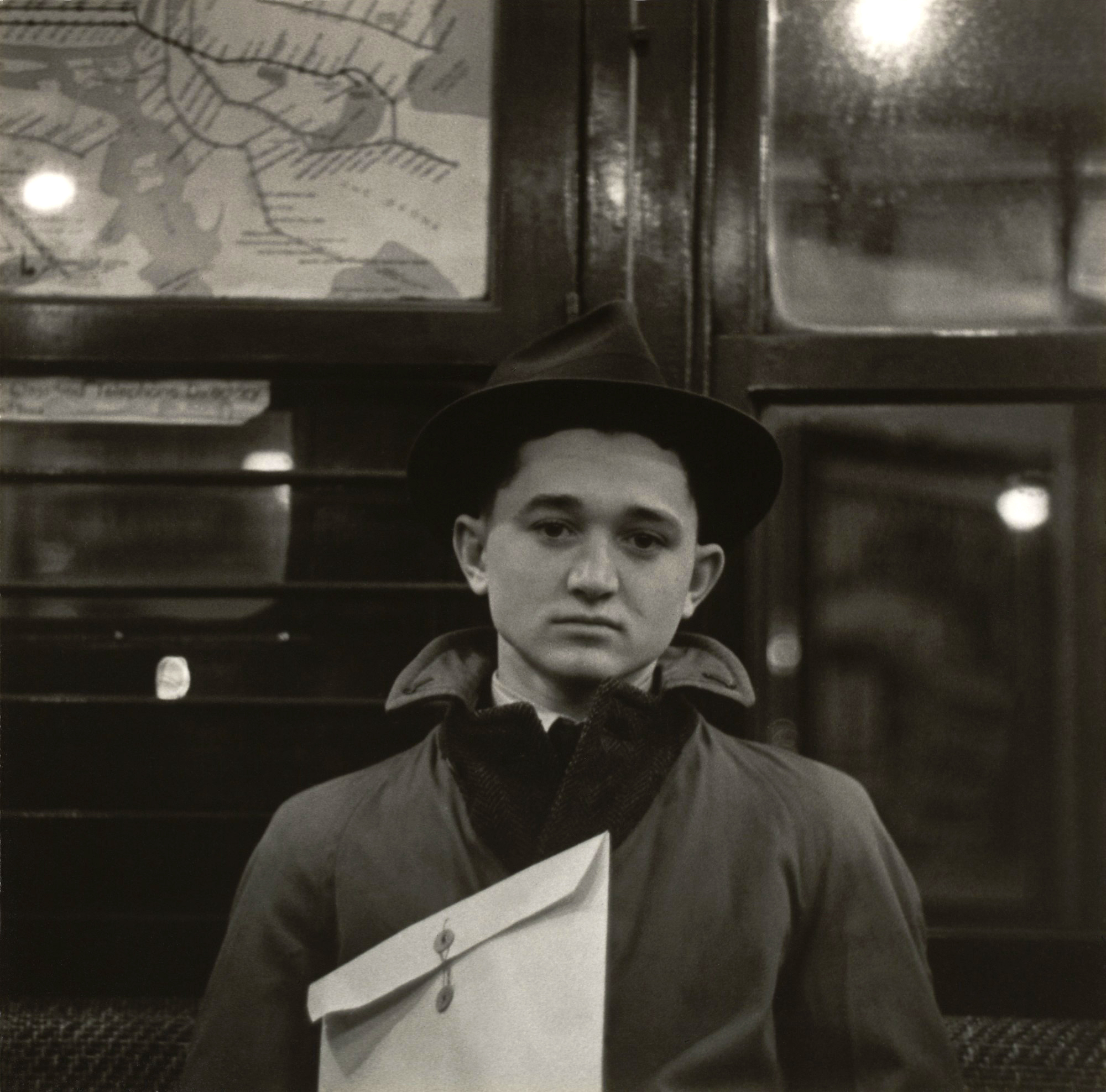

Between 1938 and 1941, Evans undertook one of the most daring projects of his career. Armed with a 35mm Contax camera concealed beneath his overcoat, he rode the New York subway and photographed fellow passengers without their knowledge. The resulting portraits — faces caught in unguarded moments of fatigue, reverie, boredom, and private thought — remained unpublished for twenty-five years. When they finally appeared as Many Are Called in 1966, they revealed an Evans quite different from the formalist of the architectural studies: intimate, almost tender, yet still governed by the same refusal to sentimentalise or idealise his subjects. The subway portraits remain among the most quietly powerful images in the history of the medium.

In 1938, the Museum of Modern Art mounted American Photographs, the first solo photography exhibition in the museum's history. Evans sequenced the images not as isolated pictures but as a visual essay, each photograph gaining meaning from its relationship to those that preceded and followed it. The accompanying book, with an essay by Lincoln Kirstein, became one of the most influential photography publications of the twentieth century. Its impact was felt not only in the documentary tradition but in the conceptual approach to the photobook as a form — an idea that would prove central to the work of Robert Frank, whose The Americans two decades later owed an explicit debt to Evans's example.

From 1945 to 1965, Evans served as a staff photographer and special photographic editor at Fortune magazine, producing carefully composed portfolios on subjects ranging from American industry to the visual culture of the railroad. In 1965, he was appointed professor of photography at the Yale University School of Art, where he taught until shortly before his death in 1975. His influence on subsequent generations of photographers has been immeasurable. Robert Frank acknowledged Evans as the single most important influence on The Americans. Lee Friedlander absorbed his attention to the American vernacular landscape. Stephen Shore carried his commitment to frontality and descriptive clarity into the realm of colour. Bernd and Hilla Becher built their typological studies of industrial architecture on principles Evans had pioneered, and through the Bechers the line extends to the New Topographics movement and to the monumental photographic tableaux of the Düsseldorf School. Evans's legacy is not a style to be imitated but a standard of looking — precise, democratic, unsentimental, and endlessly attentive to the poetry of the ordinary.