Timothy Henry O'Sullivan was born around 1840, most likely in New York City, though some accounts place his birth in Ireland, from which his parents had recently emigrated. Very little is known of his early life, and the scarcity of biographical detail has contributed to the somewhat mythic status he holds in the history of photography. What is known is that as a teenager he entered the studio of Mathew Brady, the most celebrated portrait photographer in America, and learned the wet-plate collodion process — the complex, physically demanding technique that dominated photography in the mid-nineteenth century. By the time the Civil War erupted in 1861, O'Sullivan was a skilled operator, and he accompanied Brady's teams to the front lines.

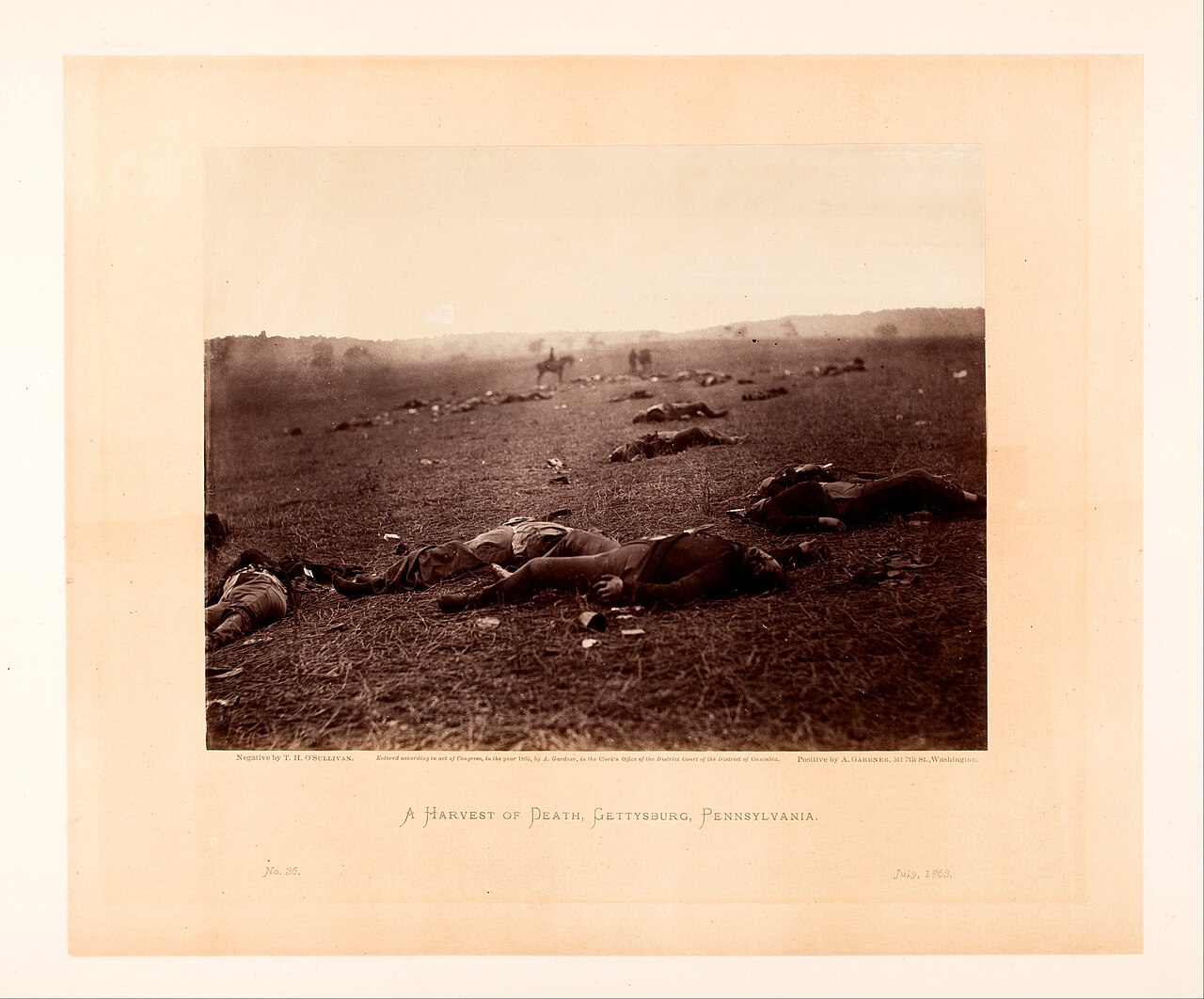

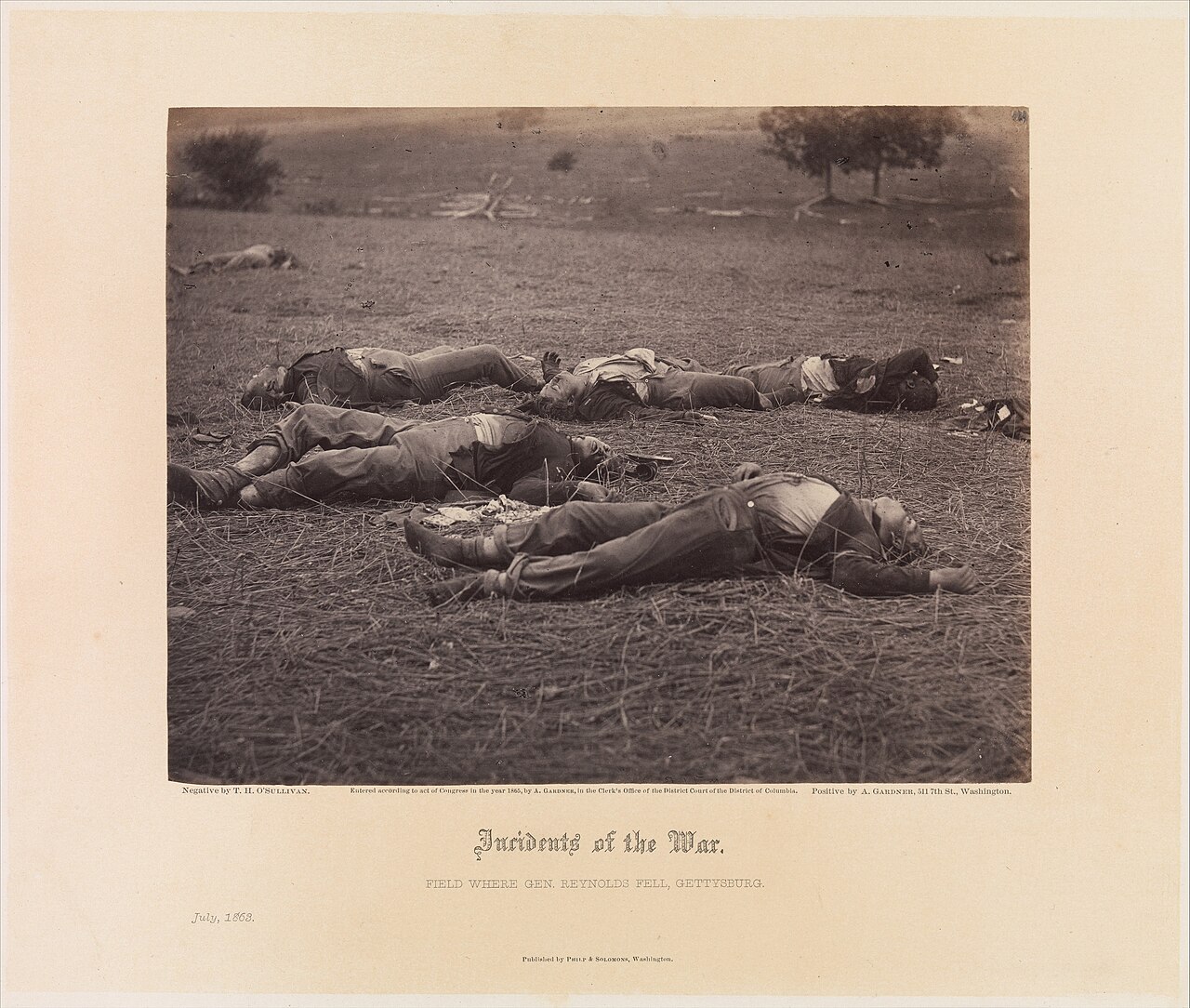

O'Sullivan's Civil War photographs rank among the most powerful images ever made of armed conflict. Working first under Brady and then under Alexander Gardner, who broke with Brady in 1862, O'Sullivan was present at some of the war's bloodiest engagements, including the battles of Beaufort, Fredericksburg, and Gettysburg. His most famous war image, A Harvest of Death, made on the Gettysburg battlefield in July 1863, depicts the bloated corpses of Union soldiers scattered across a misty field, their faces and postures suggesting not heroism but the obscene waste of industrialised killing. The photograph, published in Gardner's Photographic Sketch Book of the War in 1866, remains one of the defining images of the American Civil War and one of the earliest photographs to convey the reality of battlefield death with unflinching directness.

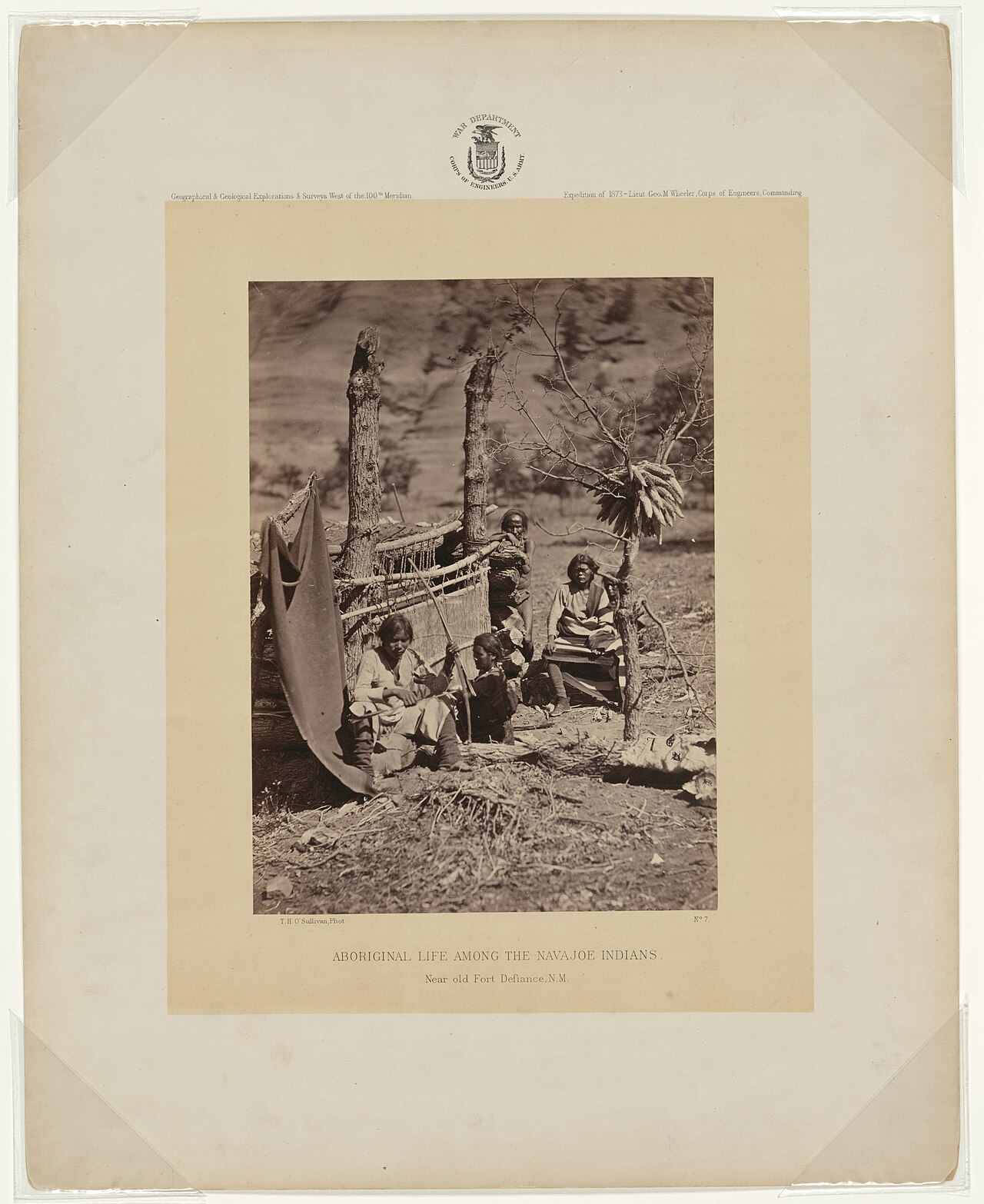

When the war ended in 1865, O'Sullivan turned his camera westward. In 1867, he joined the geological survey led by Clarence King, tasked with mapping and documenting a hundred-mile-wide corridor along the fortieth parallel from the Sierra Nevada to the Great Plains. For the next several years, O'Sullivan served as the official photographer on King's Fortieth Parallel Survey and later on the geographical surveys led by Lieutenant George Montague Wheeler. These expeditions took him through some of the most remote and spectacular terrain in North America: the alkali deserts of Nevada, the volcanic formations of the Great Basin, the canyons of the Colorado Plateau, and the ancient cliff dwellings of the Navajo and Pueblo peoples.

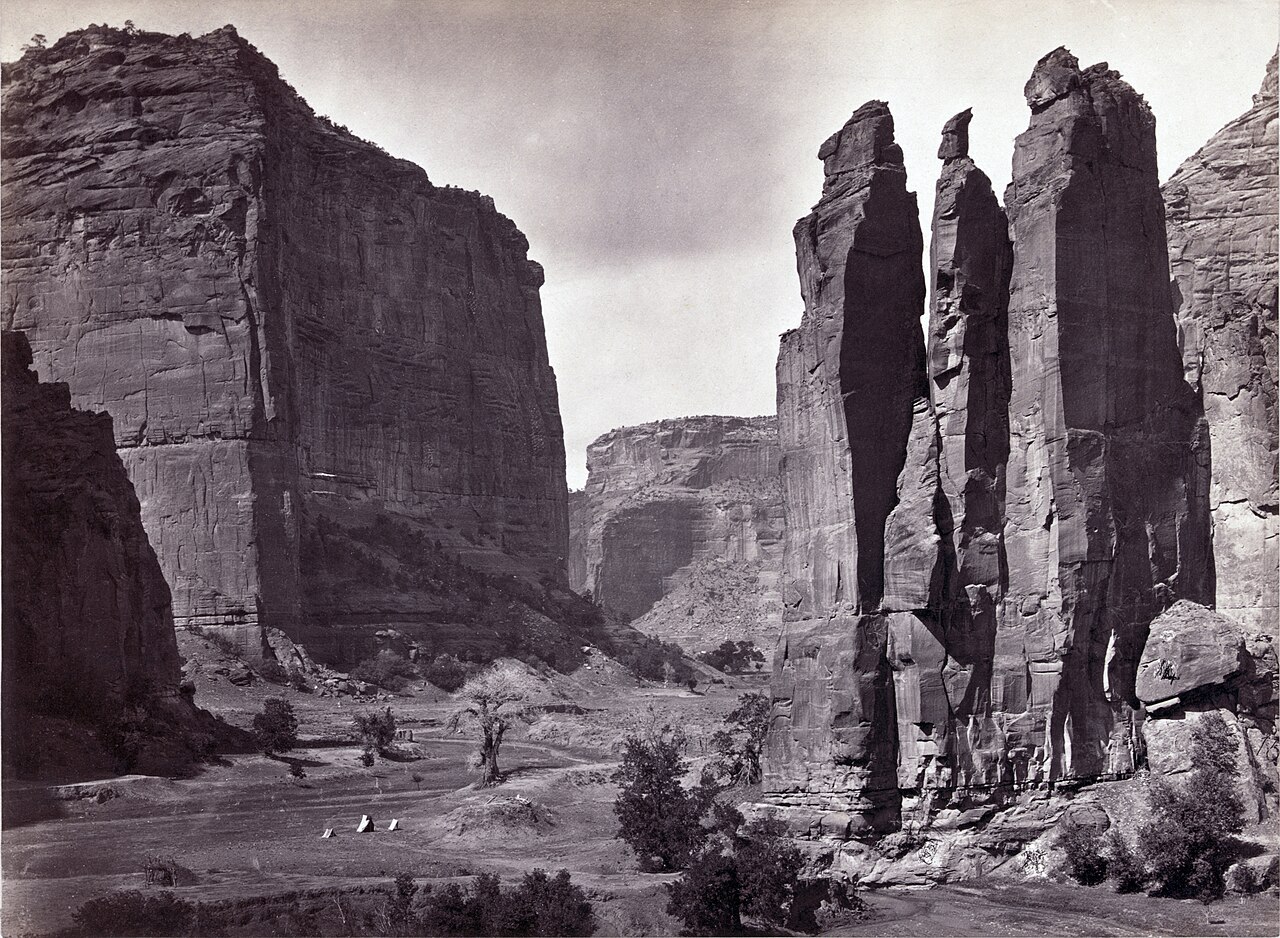

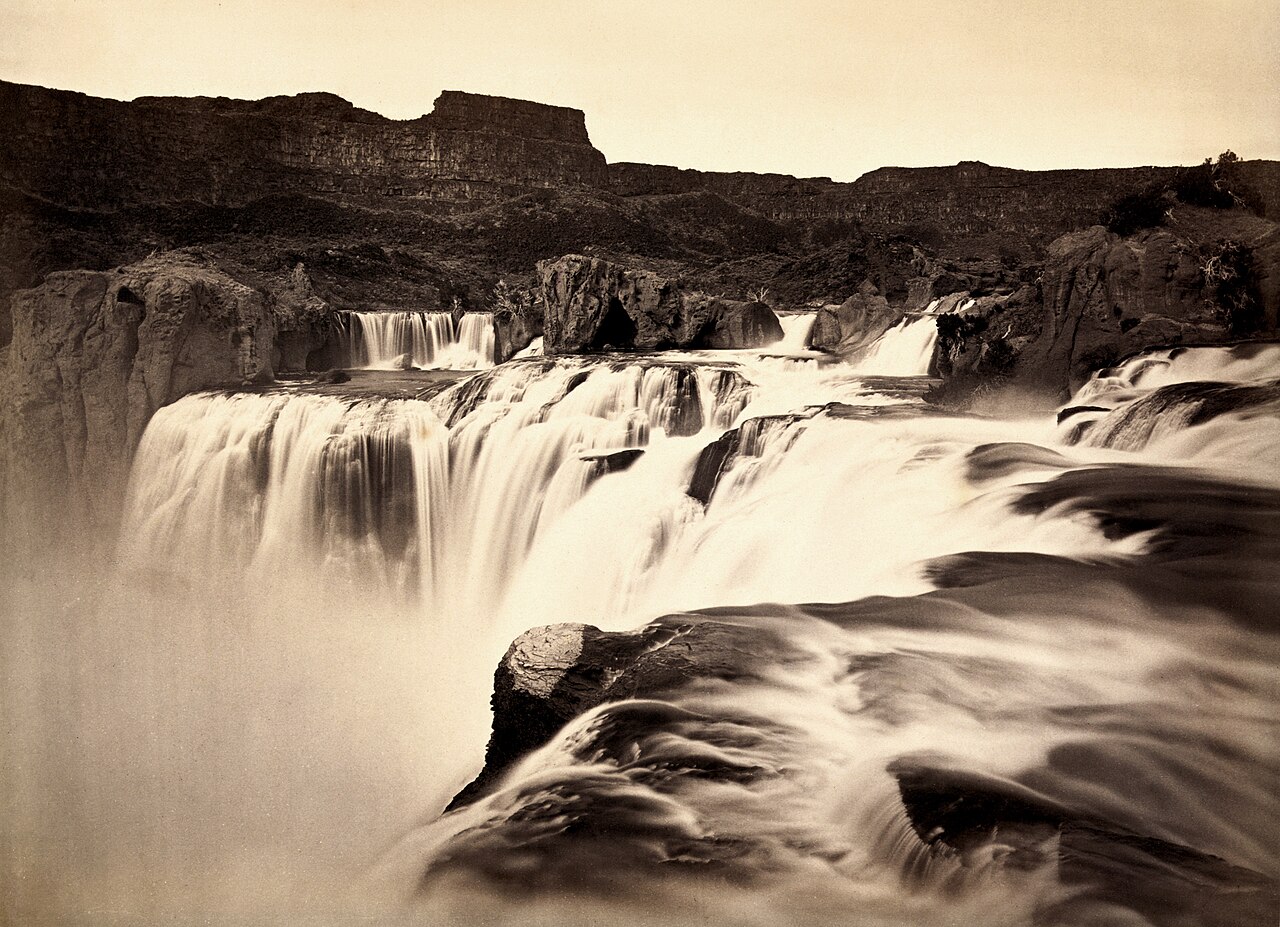

The photographs O'Sullivan produced on these surveys occupy a unique position in the history of the medium. They were made for scientific and governmental purposes — to document geological formations, water sources, mining prospects, and potential routes for railroads — and yet they possess a visual power that far exceeds their utilitarian origins. His images of the tufa domes at Pyramid Lake, the sand dunes of the Carson Desert, and the sheer walls of Canyon de Chelly are compositions of extraordinary formal intelligence, their stark contrasts of light and shadow, their radical emptiness, and their refusal of the picturesque conventions of contemporary landscape painting giving them an almost abstract quality that would not be seen again in photography for nearly a century.

O'Sullivan worked under conditions of extreme physical hardship. The wet-plate collodion process required him to prepare, expose, and develop his glass-plate negatives on the spot, carrying a portable darkroom — often a converted ambulance wagon — across deserts, through river gorges, and up mountain passes. The chemicals were volatile, the glass plates fragile, the temperatures often brutal. Despite these challenges, O'Sullivan produced images of remarkable technical quality and visual sophistication, many of them made with a stereoscopic camera that yielded three-dimensional views intended for public sale through the survey offices.

O'Sullivan's later years were marked by declining health. He had contracted tuberculosis, likely during the war years, and the disease worsened steadily through the 1870s. In 1880, he was briefly appointed photographer to the United States Treasury Department, but he was too ill to fulfil the position and resigned after only a few months. He died on Staten Island in January 1882, at the age of forty-two, largely forgotten by the public and the photographic establishment. His work was rediscovered in the twentieth century, principally through the efforts of Beaumont Newhall and Ansel Adams, who recognised in O'Sullivan's survey photographs a vision of the American landscape that anticipated the formal concerns of modernist photography by half a century.