Sophie Calle was born in Paris in 1953, the daughter of a prominent art collector and oncologist. She spent her early adulthood travelling — seven years wandering through the United States, Mexico, and elsewhere — before returning to Paris in the late 1970s with no particular plan and no formal artistic training. What she did possess was an extraordinary curiosity about the inner lives of strangers, a willingness to construct elaborate systems for investigating that curiosity, and an instinct for the point where observation becomes obsession and documentation becomes art. These qualities would make her one of the most original and influential artists of the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries.

Calle's earliest projects established the method that would define her career: the invention of a rule or constraint, followed by its rigorous execution, with the results presented as a combination of photographs and text. In The Sleepers (1979), she invited strangers to sleep in her bed for eight-hour shifts over the course of a week, photographing them at regular intervals and recording their conversations. In Suite Vénitienne (1980), she followed a man she had met at a party from Paris to Venice, tracking his movements through the city, photographing him from behind, and documenting her own increasingly obsessive pursuit in a diary that combined surveillance photographs with confessional narrative.

These early works established the tensions that would animate all of Calle's subsequent practice: between intimacy and intrusion, between the public and the private, between the artist as observer and the artist as participant. Her projects raised uncomfortable questions about the ethics of looking, the nature of consent, and the extent to which documenting a life — one's own or another's — constitutes a form of control. But they were also deeply human, often funny, and animated by a genuine fascination with the ways people construct and protect their private selves.

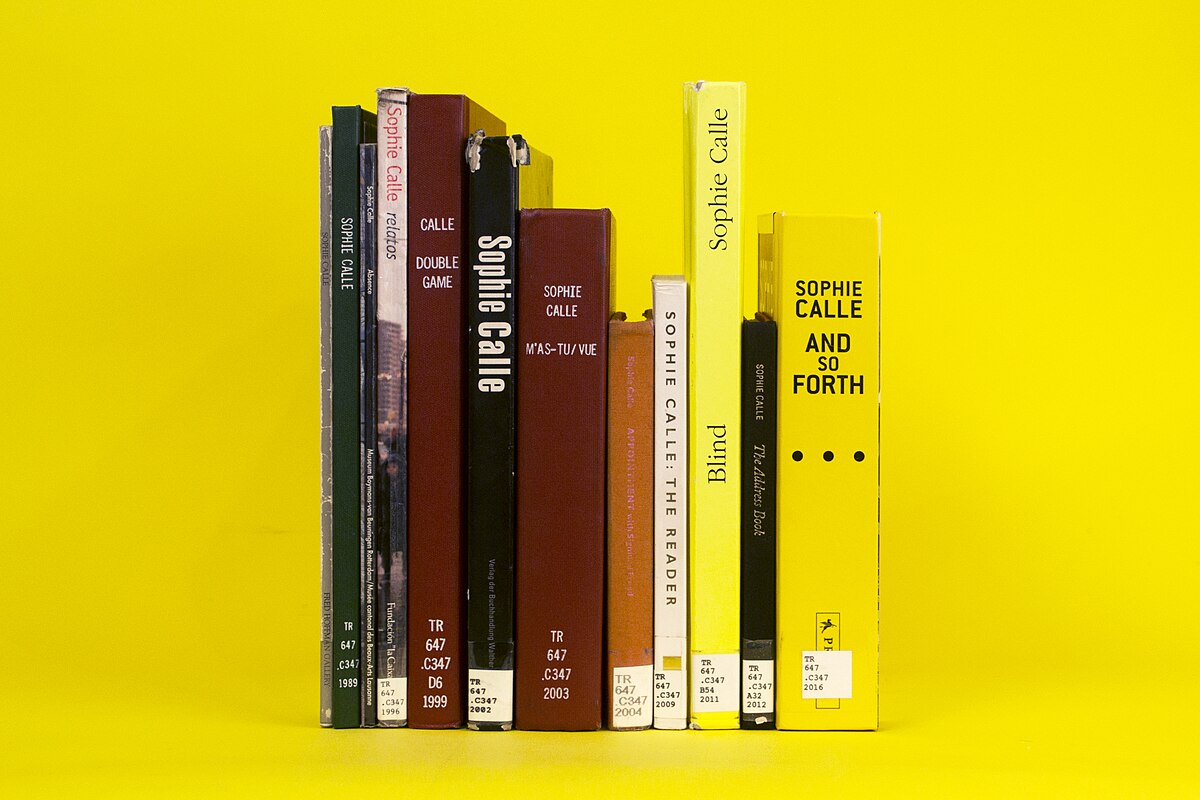

The Hotel (1981) saw Calle take a job as a chambermaid in a Venetian hotel and systematically photograph and catalogue the personal belongings of the guests whose rooms she cleaned. The Address Book (1983) began when Calle found a lost address book on a Paris street, photocopied its contents, and then contacted everyone listed in it, gradually constructing a portrait of the book's owner through the testimony of his friends and acquaintances — a project that provoked fury from the owner when it was published in Libération and raised profound questions about the boundaries between art and invasion of privacy.

Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, Calle continued to develop projects of remarkable conceptual ingenuity. The Blind (1986) asked people who had been blind from birth to describe their image of beauty, pairing their words with Calle's own photographs of what they described. Exquisite Pain (1984–2003) documented the aftermath of a devastating breakup through a ritualistic process of repetition and diminishment, telling and retelling the story of her heartbreak until the pain gradually faded. Last Seen (1991) asked museum guards and visitors to describe from memory paintings that had been stolen from the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston, displaying their words alongside photographs of the empty spaces where the paintings had hung.

In 2007, Calle represented France at the Venice Biennale with Take Care of Yourself, a monumental installation responding to a breakup email she had received from her lover. She sent the email to 107 women — among them a sharpshooter, a crossword puzzle designer, a Talmudic scholar, a forensic psychiatrist, and a clown — and asked each to interpret and respond to it according to their professional expertise. The resulting installation, filling the entire French Pavilion, was both a collective act of analysis and a wry, generous, and deeply moving meditation on the experience of being left.

Calle's work resists easy categorisation. She is neither purely a photographer nor purely a writer nor purely a conceptual artist but something that encompasses and exceeds all three. Her projects are driven by narrative logic rather than visual logic; the photographs serve not as autonomous aesthetic objects but as evidence, as traces of encounters and experiences whose meaning is completed by the accompanying text. In this sense, her work anticipates the narrative and research-based practices that have become central to contemporary art, and her influence on younger artists working at the intersection of photography, text, and performance has been profound.

What makes Calle's work endure is not merely its conceptual cleverness but its emotional honesty. Beneath the elaborate rules and constraints, there is always a deeply personal engagement with the fundamental human experiences of love, loss, curiosity, and the desire to understand other people. Her art is a sustained investigation of what it means to pay attention to another human being, and of the ethical complexities that attend that attention. It is work that is as likely to make you laugh as to unsettle you, and its capacity to do both at once is the surest sign of its quality.