Sebastião Ribeiro Salgado was born on 8 February 1944 in Aimorés, a small town in the state of Minas Gerais, Brazil, surrounded by the lush Atlantic Forest that would, decades later, become central to his life's mission. The son of a cattle rancher, he grew up on a farm in the Rio Doce valley, one of eight children in a close-knit family. His early years were shaped by the rhythms of rural Brazilian life — the land, the seasons, the labour of working people — experiences that planted the seeds of the epic, humanist vision that would come to define his photography.

Salgado did not begin as a photographer. He trained as an economist, earning a master's degree from the University of São Paulo before moving to Paris in 1969 with his wife, Lélia Wanick Salgado, to pursue doctoral studies at the École Nationale de la Statistique et de l'Administration Économique. He took positions with the International Coffee Organization and the World Bank, travelling to Africa on development missions. It was during these journeys, using Lélia's camera, that he discovered photography's power to bear witness. By the early 1970s, he had abandoned economics entirely, choosing to document the world rather than quantify it.

His early career moved swiftly through the institutions of European photojournalism. He worked with the Sygma and Gamma agencies before joining Magnum Photos in 1979, where he remained for fifteen years. At Magnum, Salgado developed the method that would become his signature: immersive, long-form projects spanning years and entire continents, each one a sustained meditation on a single monumental theme. Rather than chasing individual news events, he embedded himself within the great currents of human experience — labour, displacement, the relationship between people and the earth — producing bodies of work whose cumulative power dwarfed anything a single assignment could achieve.

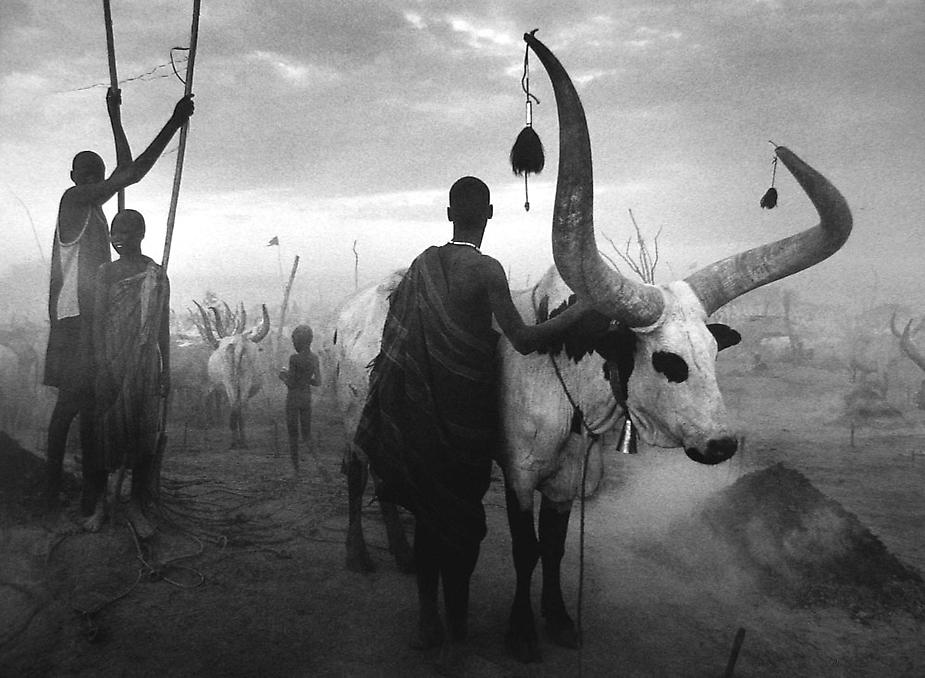

The first of these defining projects was Workers, published in 1993. Over six years and across twenty-six countries, Salgado documented manual labour in what he recognised as its last great era — from the ant-like swarms of gold miners at Serra Pelada in Brazil to the apocalyptic oil fires of Kuwait, from Indonesian sulphur carriers to Cuban sugarcane cutters. The resulting images, printed in the rich, luminous black-and-white that had become his hallmark, transformed the human body at labour into something monumental. Workers was not merely a documentary record; it was an elegy for a way of life that mechanisation was sweeping from the world.

In 1994, Salgado and Lélia founded Amazonas Images, their own agency, to maintain complete control over the production and distribution of his work. That same year, he began covering the Rwandan genocide and the catastrophic refugee crisis in Zaire, producing images of human suffering so powerful that they provoked both profound admiration and pointed criticism. His second epic project, Migrations, published in 2000, surveyed human displacement across thirty-five countries over six years — refugees, economic migrants, and the dispossessed of every continent. It remains one of the most ambitious undertakings in the history of documentary photography.

Salgado's visual style is unmistakable: sweeping, dramatic black-and-white compositions that use light the way a Renaissance painter would, sculpting human figures and landscapes with chiaroscuro effects that lend his subjects an almost biblical grandeur. His large-format prints shimmer with tonal range, every shadow and highlight calibrated to maximum emotional effect. This approach has earned him both fervent admirers and vocal critics. Writers such as Susan Sontag and Ingrid Sischy argued that his images aestheticise suffering, that the formal beauty of his compositions risks turning poverty, famine, and displacement into spectacle. Salgado has consistently rejected this criticism, insisting that dignity, not exploitation, is the foundation of his work, and that beauty is a means of compelling the viewer to look, to engage, and ultimately to act.

His third great project, Genesis, published in 2013 after eight years of fieldwork, marked a dramatic shift in subject. Rather than documenting human labour and migration, Salgado turned his lens on the planet itself — the pristine landscapes, wildlife, and indigenous peoples of the last untouched regions of the earth, from Antarctica to the Amazon, from the Sahara to the forests of New Guinea. Genesis was a love letter to the natural world, an argument in images that vast stretches of the planet remain as they were before industrialisation, and that they are worth fighting to preserve.

That argument was deeply personal. Returning to his family's ranch in Minas Gerais in the late 1990s, Salgado and Lélia found the once-lush Atlantic Forest reduced to barren, eroded wasteland by decades of deforestation and cattle ranching. Together they founded Instituto Terra, an environmental organisation dedicated to reforestation. Over two decades, they planted more than two million trees, restoring over 1,700 acres of degraded land to thriving forest — an achievement documented in Wim Wenders's 2014 documentary The Salt of the Earth, which brought Salgado's life and work to a global cinema audience and earned an Academy Award nomination. The reforestation project stands as a testament to Salgado's belief that bearing witness is not enough — that the photographer must also act.