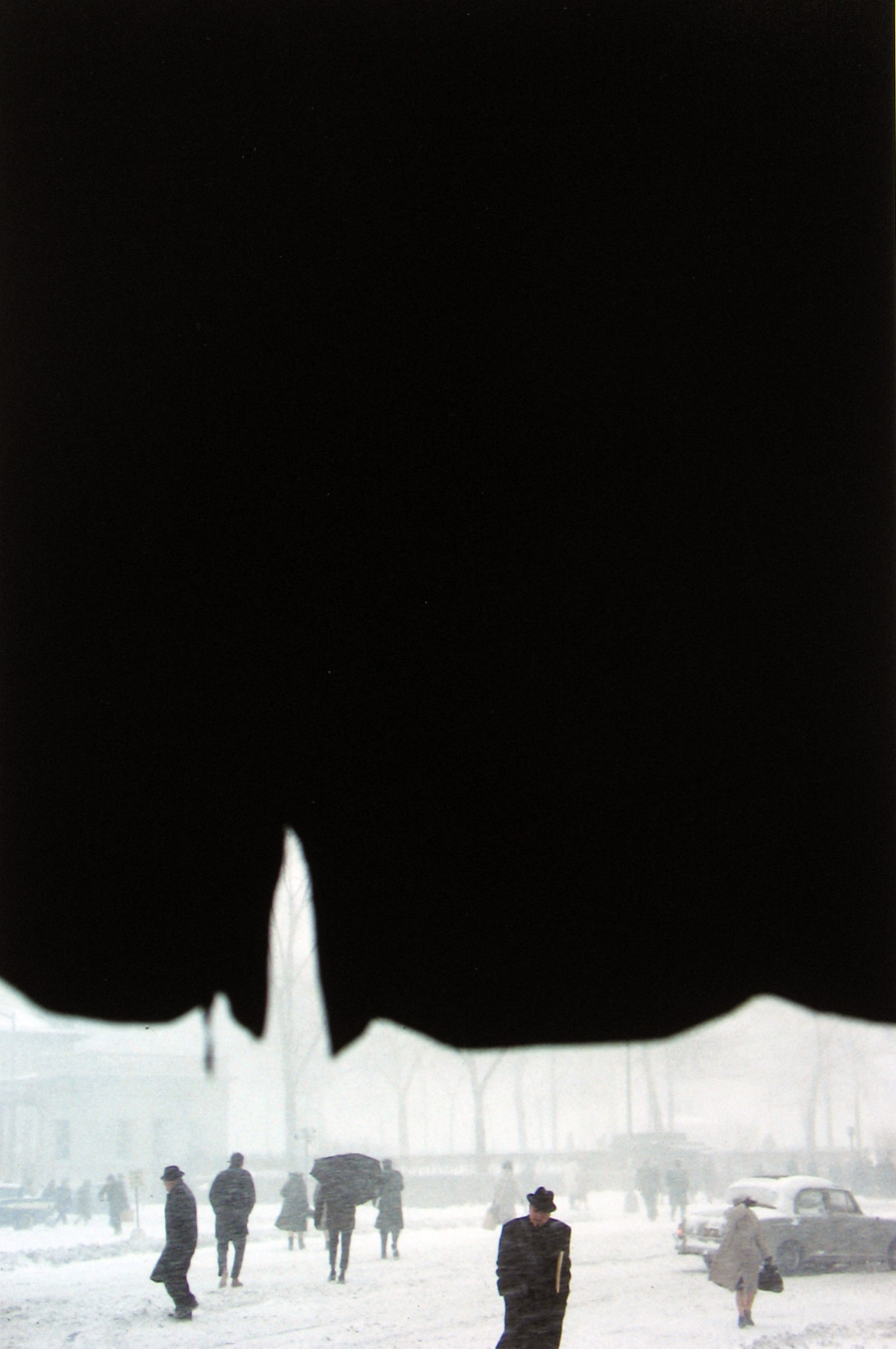

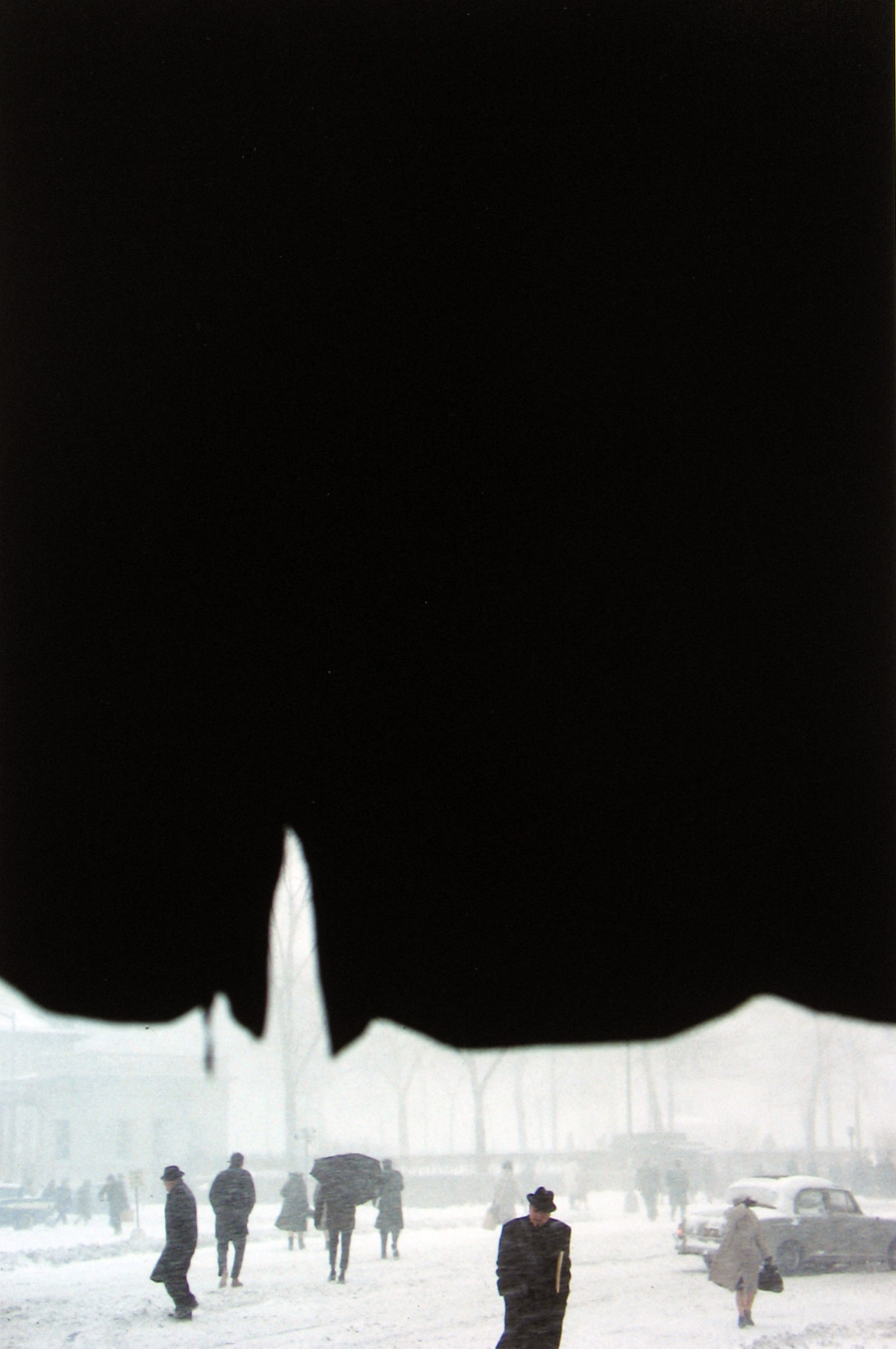

Snow

c. 1960

Footprints

c. 1950

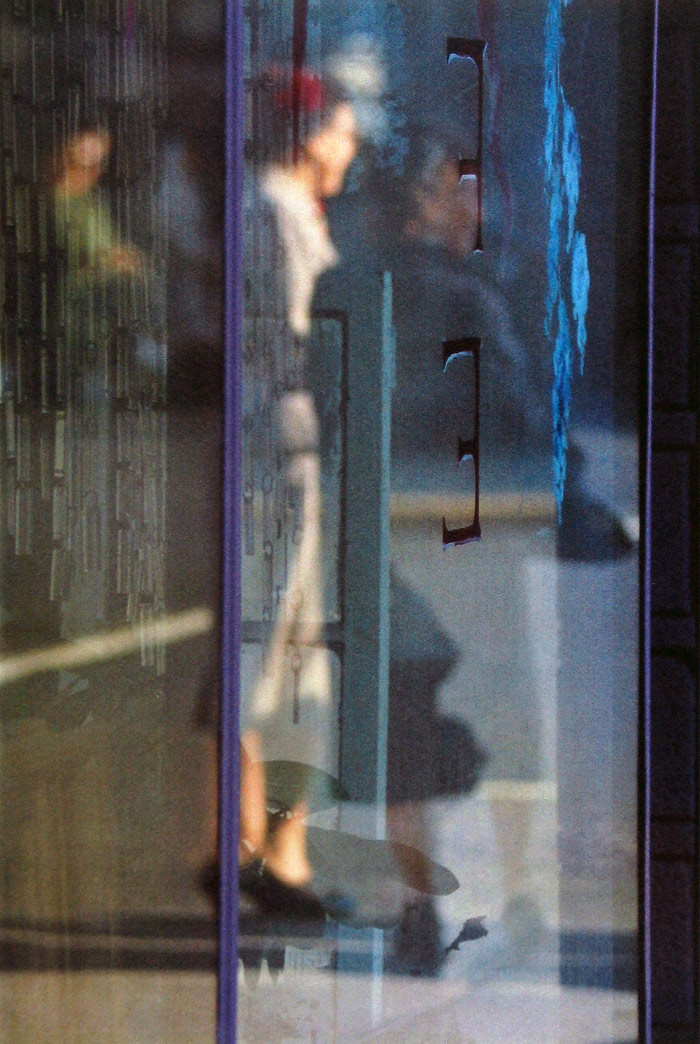

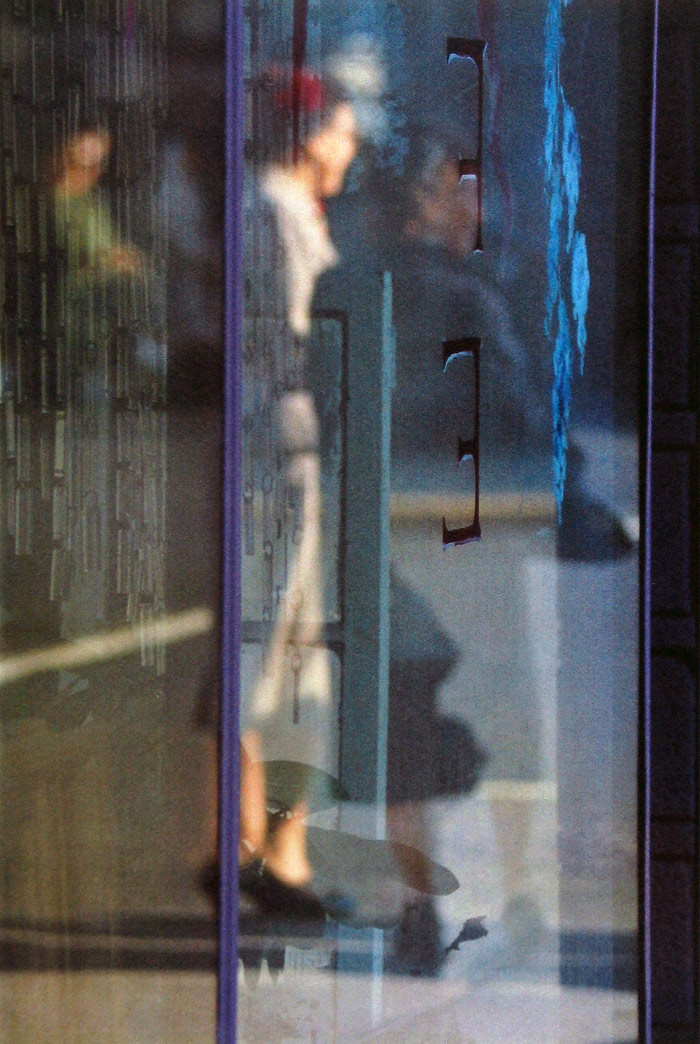

Through Boards

1957

Canopy

c. 1958

Red Umbrella

c. 1958

Taxi

c. 1957

Walking

c. 1956

Haircut

c. 1956

The quiet revolutionary of colour photography, whose painterly images of rain-streaked windows, oblique reflections, and half-glimpsed figures transformed the New York street into an intimate, abstract canvas decades before the art world was ready.

1923, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania – 2013, New York City — American

Snow

c. 1960

Footprints

c. 1950

Through Boards

1957

Canopy

c. 1958

Red Umbrella

c. 1958

Taxi

c. 1957

Walking

c. 1956

Haircut

c. 1956

Saul Leiter was born in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, in 1923, the eldest son of a distinguished Talmudic scholar who fully expected his boy to follow him into the rabbinate. Leiter was a gifted student of religious texts, but from an early age he found himself drawn not to scripture but to painting. His mother gave him his first camera when he was twelve, though it would be years before he took the instrument seriously. The tension between his father's expectations and his own restless artistic temperament defined his youth. In 1946, at the age of twenty-three, he made the decisive break: he left Pittsburgh for New York City, abandoning his religious studies and his father's world for good.

In New York, Leiter immersed himself in the downtown art scene, befriending the Abstract Expressionist painter Richard Pousette-Dart, who became an early mentor and kindred spirit. Through Pousette-Dart he encountered the work of the New York School painters — the bold colours, the gestural abstraction, the conviction that feeling could be communicated through pure form. Leiter painted seriously and continued to do so throughout his life, but by the late 1940s the camera had begun to claim an equal share of his attention. He started shooting on the streets of the East Village and the Lower East Side, working in both black and white and, crucially, in colour — using Kodachrome slide film to capture the city in rich, saturated hues that no serious photographer of the era thought worthy of art.

What set Leiter apart from every other street photographer of his generation was his painterly instinct for composition. Where Henri Cartier-Bresson sought the decisive moment and Robert Frank pursued the raw nerve of American life, Leiter was drawn to obstruction, reflection, and partial concealment. He photographed through rain-streaked windows, behind steamed glass, past awnings and doorways and the blurred edges of umbrellas. His subjects — pedestrians, taxi cabs, shop fronts, snow-covered streets — were often half-hidden, glimpsed obliquely, layered behind translucent veils of colour. The effect was less documentary than atmospheric, closer to the intimate domestic interiors of Pierre Bonnard and Édouard Vuillard than to anything in the photographic tradition of the time.

Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, Leiter supported himself through commercial fashion photography, shooting for Harper's Bazaar, Elle, and Vogue under the art direction of figures such as Henry Wolf and Alexey Brodovitch. His fashion work was elegant and inventive, marked by the same feeling for colour and composition that distinguished his personal photographs. But Leiter never confused the two pursuits. The fashion assignments paid the rent on his cramped East Village apartment; the personal work — the colour slides he shot on his daily walks through the neighbourhood — was made for no one but himself, with no thought of exhibition or publication.

This indifference to recognition was not a pose. While his contemporaries William Klein and Robert Frank achieved fame in the 1950s and William Eggleston was celebrated in the 1970s as the pioneer of colour art photography, Leiter continued working in quiet obscurity. He had been shooting sophisticated colour on the streets of New York a full two decades before Eggleston's landmark 1976 exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, yet he made no effort to bring his work to public attention. He simply went on photographing, painting, and living in the same small apartment on East 10th Street that he had occupied since the 1950s, accumulating tens of thousands of colour slides in boxes that he rarely bothered to edit or organise.

The rediscovery came in 2006, when the German publisher Steidl released Early Color, a collection of Leiter's 1940s and 1950s colour street photography. The book was a revelation. Critics and photographers who had never heard of Leiter were astonished to find a body of work that anticipated by decades the colour revolution attributed to Eggleston and Stephen Shore. The images were not only historically significant but aesthetically extraordinary — luminous, tender, abstract, and suffused with a quality of attention that felt entirely unlike anything else in the medium. A flurry of exhibitions, monographs, and retrospectives followed. The Foundation Henri Cartier-Bresson in Paris mounted a major exhibition in 2008. All About Saul Leiter, a comprehensive retrospective volume, appeared in 2011.

Leiter accepted his late fame with characteristic bemusement and mild discomfort. He gave interviews reluctantly and spoke with self-deprecating wit about his years of invisibility. He continued to live in his East Village apartment, surrounded by decades of paintings, photographs, and accumulated clutter, and he continued to photograph on his daily walks until his health no longer permitted it. In 2012, the documentary film In No Great Hurry: 13 Lessons in Life with Saul Leiter, directed by Tomas Leach, introduced him to a still wider audience, capturing the warmth, humour, and philosophical quietude of a man who had spent a lifetime making art without seeking attention for it.

Saul Leiter died in New York City on 26 November 2013, at the age of eighty-nine. His legacy has only grown in the years since. He is now recognised not merely as a forgotten pioneer of colour photography but as one of the most original visual artists of the twentieth century — a photographer whose painterly sensibility, whose feeling for the accidental beauty of obstructed views and rain-blurred streets, opened an entirely new way of seeing the urban world. His influence is visible in the work of countless contemporary photographers who have absorbed his lesson that the most profound images are often found not in the dramatic or the decisive, but in the quiet, the oblique, and the half-seen.

I spent a great deal of my life being ignored. I was always very happy that way. Being ignored is a great privilege. Saul Leiter

The landmark Steidl publication that revealed Leiter's extraordinary 1940s and 1950s colour street photography to the world, rewriting the accepted history of colour in art photography.

Intimate, painterly nude studies made in Leiter's East Village apartment over several decades, suffused with the same tender, oblique sensibility that characterises his street work.

A comprehensive retrospective volume bringing together colour and black-and-white street photography, fashion work, and paintings to reveal the full breadth of Leiter's artistic vision.

Born in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, the son of a noted Talmudic scholar.

Abandons religious studies and moves to New York City to pursue art, befriending Abstract Expressionist painter Richard Pousette-Dart.

Begins shooting colour photography on the streets of New York using Kodachrome slide film — decades before colour is accepted as a serious artistic medium.

Included in the Museum of Modern Art exhibition Always the Young Strangers, an early acknowledgement of his work.

Begins regular fashion photography assignments for Harper's Bazaar, later extending to Elle and Vogue.

Continues photographing and painting privately in his East Village apartment, making no effort to exhibit or publish his personal colour work.

Early Color published by Steidl, revealing his pioneering 1940s–50s colour street photography and sparking international recognition.

Major exhibition at the Foundation Henri Cartier-Bresson in Paris establishes Leiter's reputation in Europe.

Documentary film In No Great Hurry: 13 Lessons in Life with Saul Leiter directed by Tomas Leach introduces him to a wider audience.

Dies in New York City at the age of eighty-nine, recognised as one of the most original colour photographers of the twentieth century.

Interested in discussing photography, collaboration, or just want to say hello? I’d love to hear from you.

Contact →