Sally Mann was born in Lexington, Virginia, in 1951, the daughter of Robert Munger, a general practitioner with a deep love of literature and the natural world, and Elizabeth Evans Munger, a woman of fierce intelligence and quiet reserve. She grew up on the family's farm in the Shenandoah Valley, a landscape of rolling hills, dense forests, and slow-moving rivers that would become the central subject of much of her life's work. Her father, an atheist and a freethinker in the conservative culture of the rural South, encouraged in her a habit of fearless inquiry and a deep sensitivity to the natural world. Mann has spoken often of the formative influence of her childhood — the freedom to roam, the proximity to both beauty and decay, and the pervasive sense of history that saturates every acre of Virginia soil.

Mann studied at Bennington College and the Praeger School of Photography before completing a master's degree in creative writing at Hollins University. Her early photographic work included architectural studies and landscapes of the American South, but it was with the publication of At Twelve: Portraits of Young Women in 1988 that she first attracted significant attention. The book presented photographs of adolescent girls on the cusp of womanhood, images that were tender, psychologically complex, and subtly unsettling in their refusal to sentimentalise the experience of growing up. The critical response was largely positive, but the book also foreshadowed the controversy that would surround her next and most celebrated body of work.

Immediate Family, published in 1992, presented photographs of Mann's three children — Emmett, Jessie, and Virginia — taken over a period of years on the family's farm in Virginia. The images were intimate, unsentimental, and often startlingly direct: children playing naked in summer, sleeping, bleeding from minor injuries, posing with the self-conscious theatricality that children naturally adopt. Printed as large-format silver gelatin prints with the rich tonality and atmospheric depth that would become Mann's signature, they possessed a visual gravity that elevated the domestic and the everyday to the level of classical art. The book was an immediate critical sensation and an equally immediate source of controversy.

Critics and commentators argued fiercely about the ethics of photographing one's own children in states of undress, and about the boundary between artistic expression and parental responsibility. Mann was accused of exploitation and defended as a visionary. The debate, which played out in the pages of The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, and Time magazine, made her one of the most discussed artists in America. Mann weathered the storm with characteristic forthrightness, arguing that the photographs were made collaboratively with her children, that they reflected the ordinary reality of childhood lived close to nature, and that the discomfort they provoked revealed more about the viewer's anxieties than about anything in the images themselves.

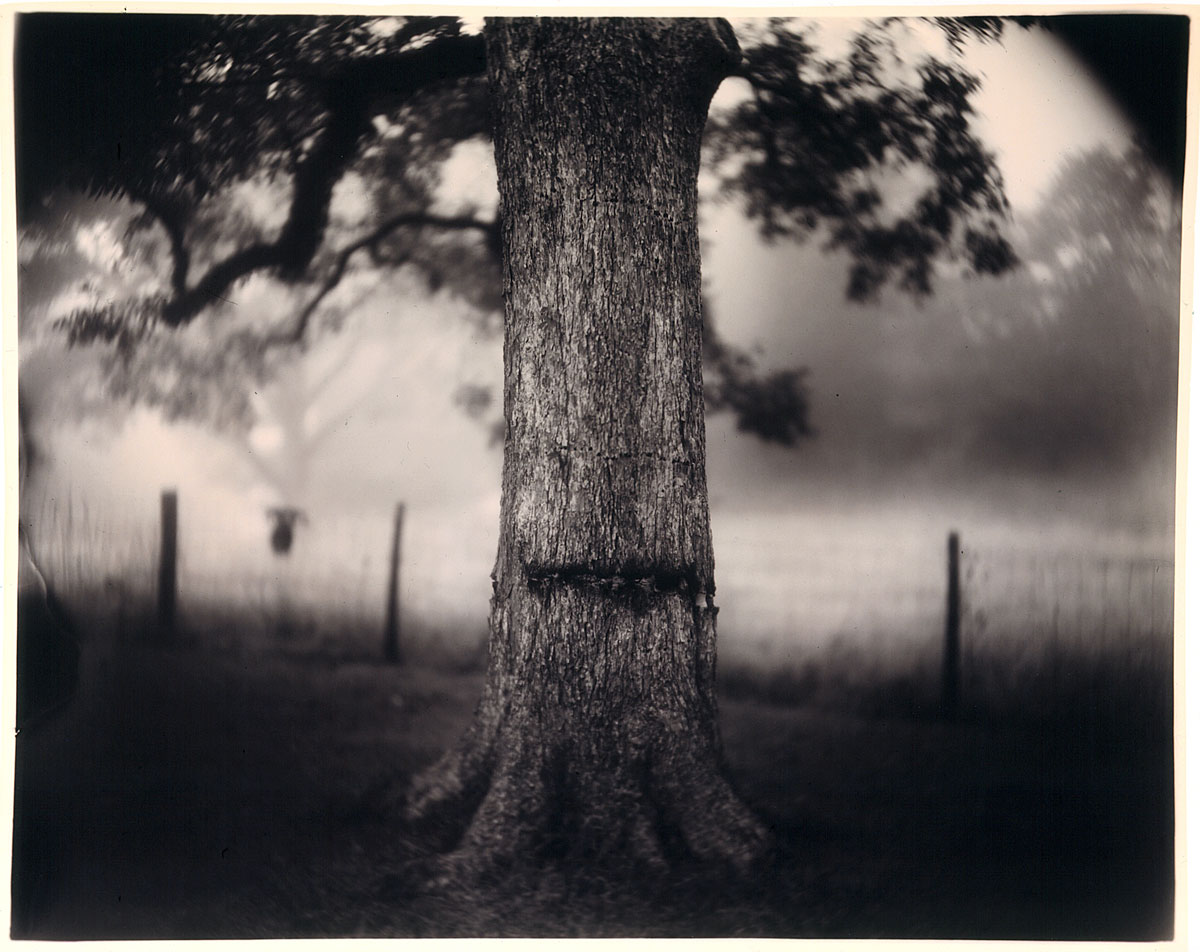

After Immediate Family, Mann turned her attention to the Southern landscape itself. The Deep South series, begun in the mid-1990s, presented the swamps, forests, and riverbanks of Mississippi, Louisiana, and Virginia in images of extraordinary atmospheric power. Working with an 8x10 view camera and deliberately embracing the imperfections of the wet plate collodion process — light leaks, chemical streaks, areas of blur and dissolution — Mann produced photographs that seemed to emanate from the landscape's own memory, haunted by the violence and sorrow of slavery, the Civil War, and the long aftermath of Southern history. These were not documentary images but meditations, dense with allusion and suffused with a sense of time as a physical, almost geological force.

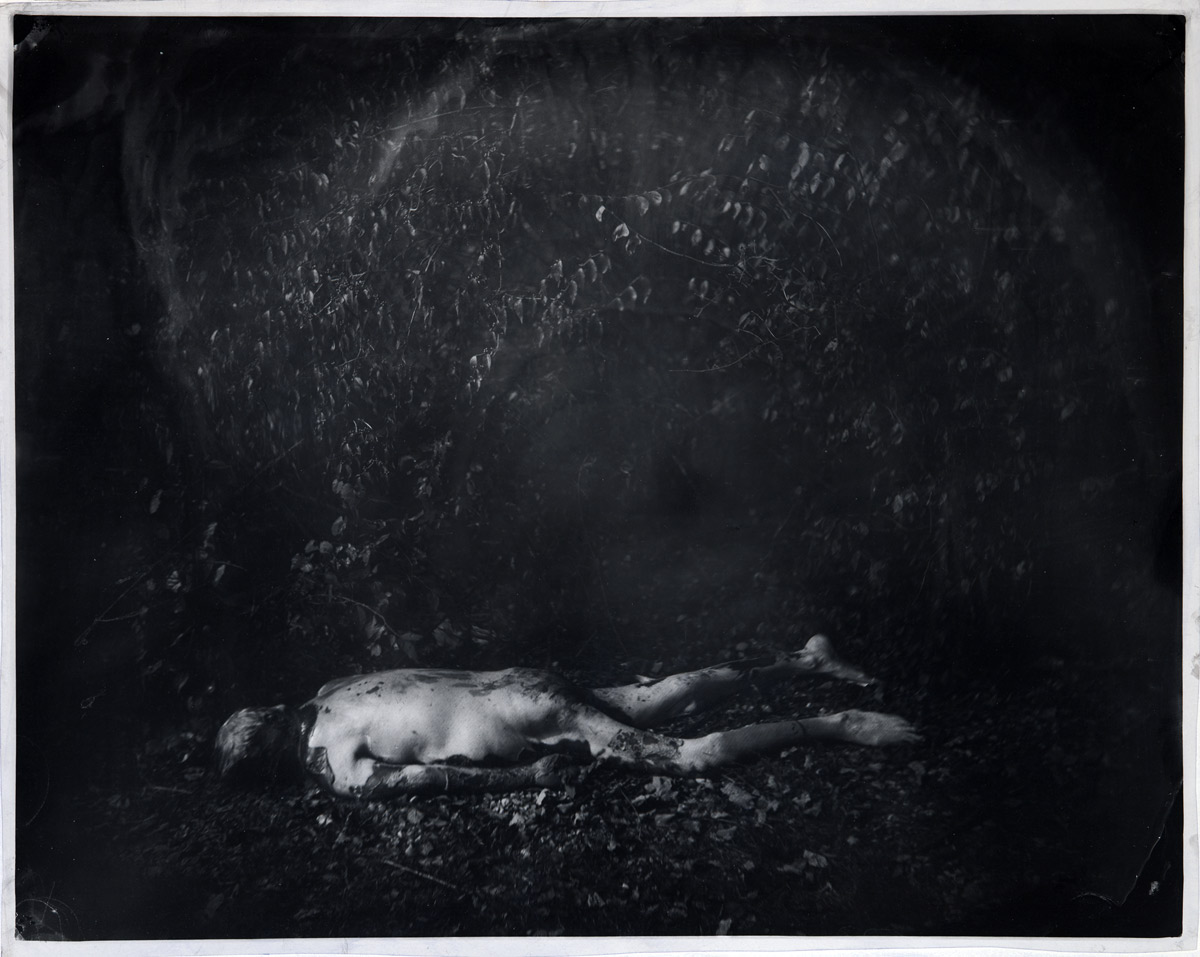

The theme of mortality, always present in Mann's work, became explicit in What Remains, a five-part series that explored decomposition, death, and the body's return to the earth. The project included photographs taken at the University of Tennessee's Forensic Anthropology Center, where human bodies are left to decompose in controlled conditions, as well as images of Civil War battlefields and of the landscape surrounding the site where an armed fugitive had died on Mann's own property. The series was unflinching in its confrontation with death, yet infused with Mann's characteristic lyricism and her deep conviction that beauty and decay are not opposites but inseparable aspects of the same reality.

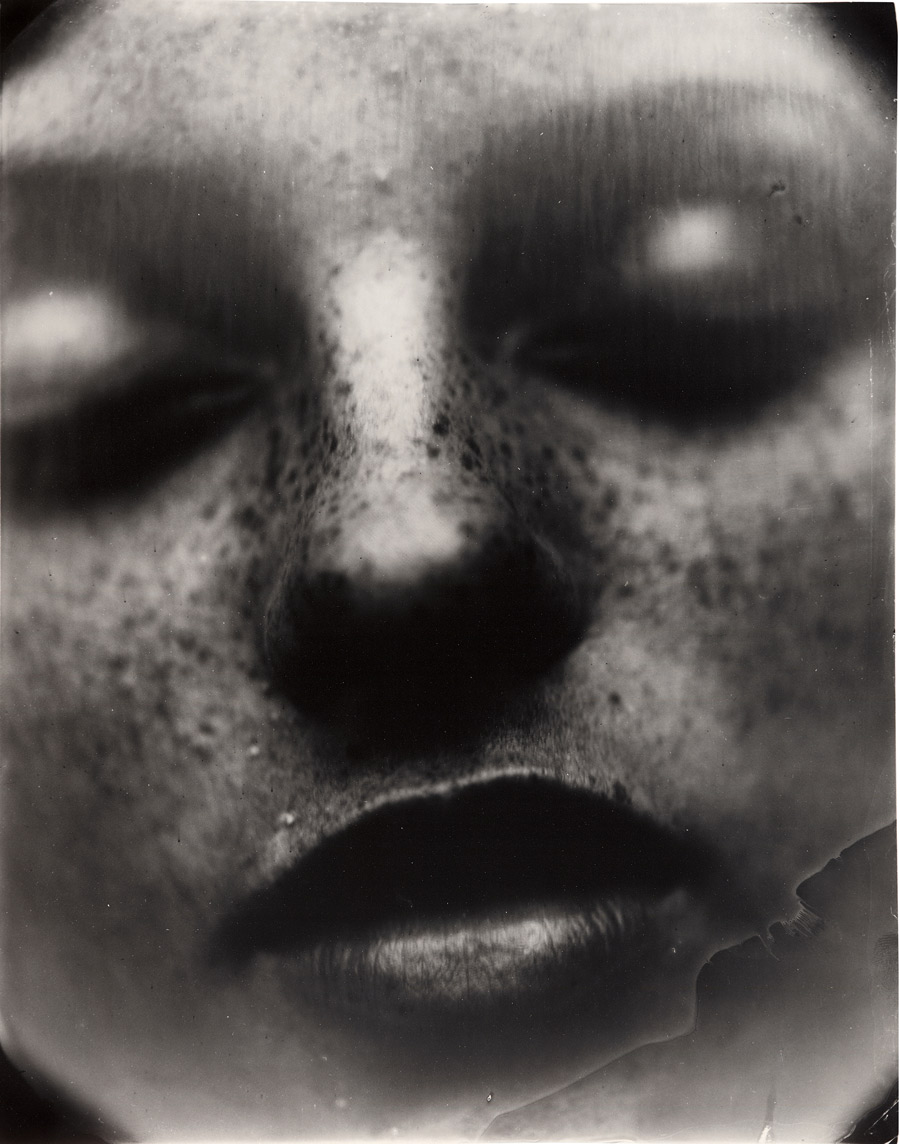

In Proud Flesh, Mann turned the camera on her husband, Larry Mann, who had been diagnosed with late-onset muscular dystrophy. The resulting portraits, made over several years as the disease progressively altered his body, are among the most powerful and tender images she has ever produced. Using the same antiquarian processes that she had brought to the Southern landscape, Mann photographed Larry's changing form with an intimacy and a directness that refused both pity and denial, creating images that honour the body's vulnerability while insisting on its continuing dignity and beauty.

Mann's memoir, Hold Still, published in 2015 and nominated for the National Book Award, wove together family history, Southern history, and reflections on the making of her photographs into a narrative of remarkable candour and literary quality. The book confirmed what her photographs had long suggested: that Mann is not only a visual artist of the first order but also a writer of exceptional power, capable of articulating the philosophical and emotional dimensions of her work with a precision and eloquence that few photographers have ever achieved.