Swiss-born observer of America's soul, creator of the most influential photobook of the twentieth century, and a restless innovator who redefined the relationship between photography and personal expression.

1924, Zürich, Switzerland – 2019, Inverness, Nova Scotia — Swiss-American

Robert Frank arrived in the United States in 1947 with a Swiss passport, a working knowledge of several European photographic traditions, and an eye that would transform the medium forever. Born in Zürich in 1924 to a Jewish family of German descent, he had apprenticed with photographers in Switzerland and learned the discipline of careful, technically accomplished image-making. But it was the roughness of life in postwar New York, the chaotic energy of the streets, the jazz clubs, the diners, and the long American highways stretching toward horizons he had never seen, that liberated something in his seeing. Within a decade of his arrival, he would produce a body of work that fundamentally altered the course of photography.

Through the late 1940s and early 1950s, Frank worked as a freelance photographer for magazines including Harper's Bazaar, Vogue, and Fortune, while pursuing his own projects on the side. He travelled to Peru, to London, to Paris, to Wales, building a portfolio of street photography that was already distinctive in its refusal of conventional compositional tidiness. His images tilted, blurred, cut figures off at the edges, and found their subjects in the overlooked corners of the frame. He was influenced by Walker Evans's cool documentary precision, but where Evans composed with architectural clarity, Frank improvised, letting the disorder of the world enter the picture.

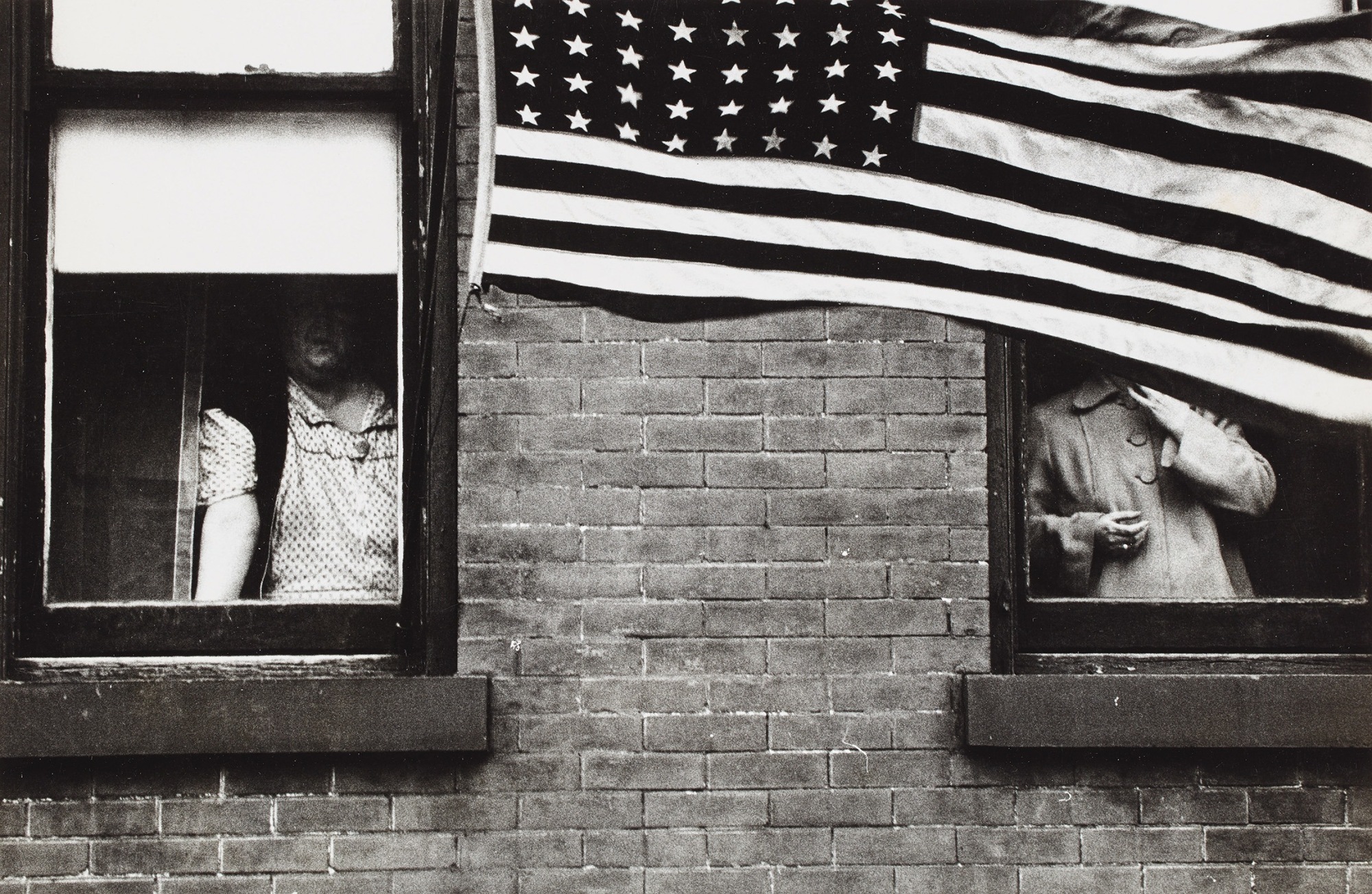

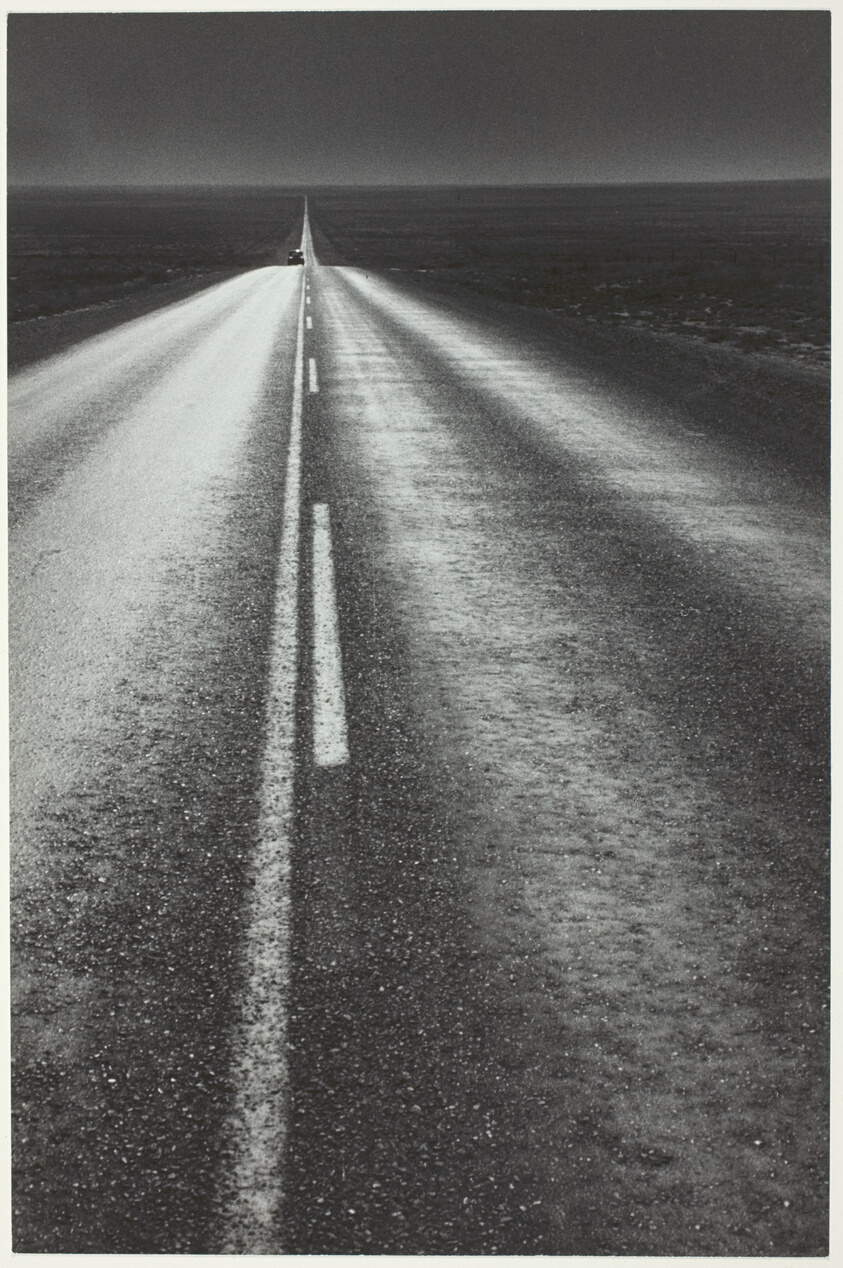

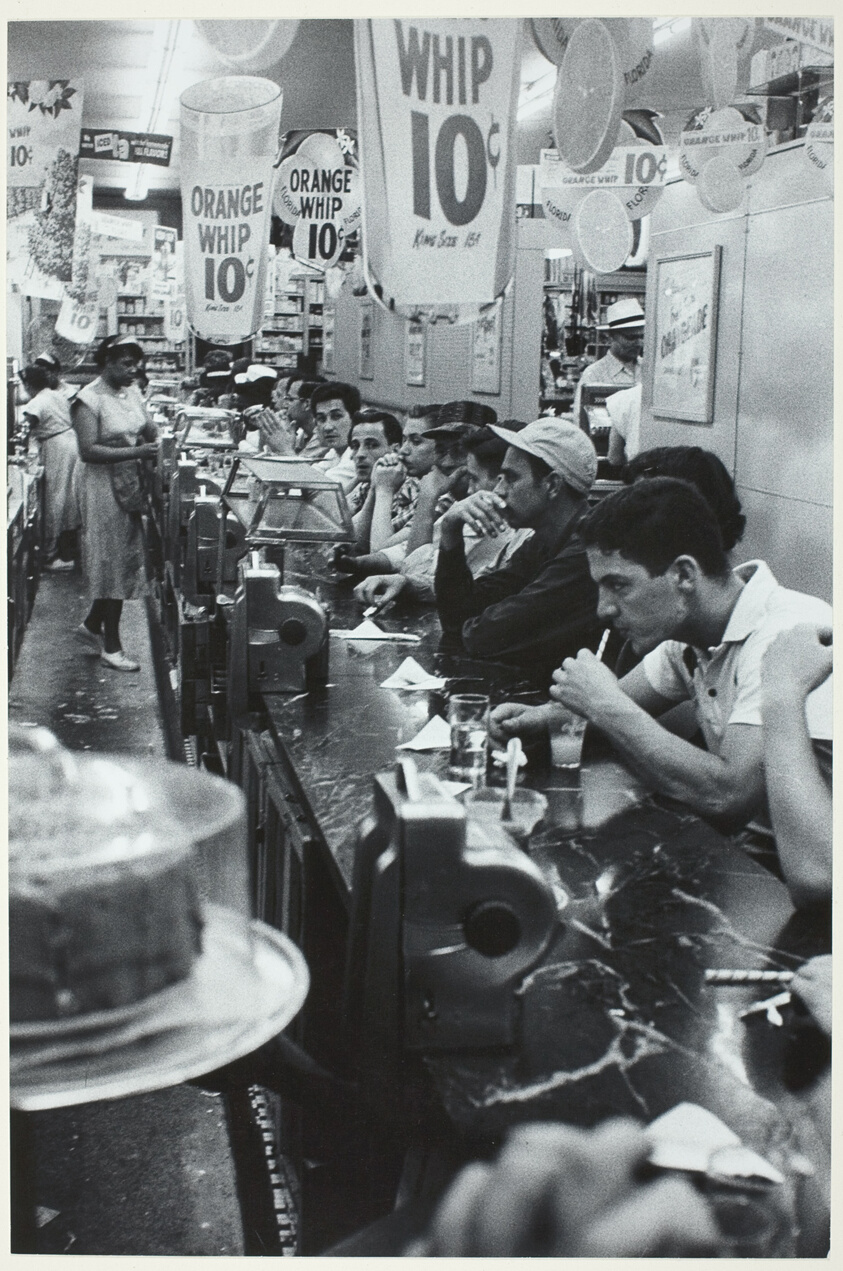

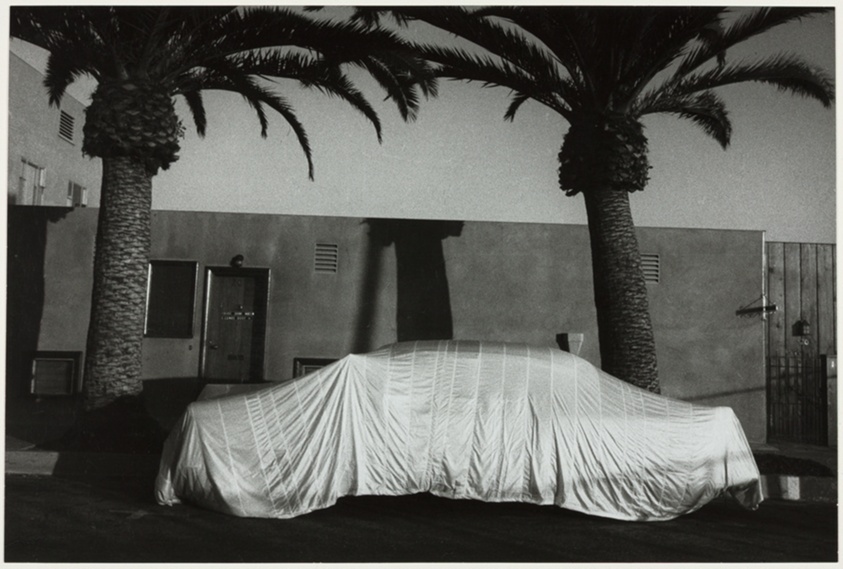

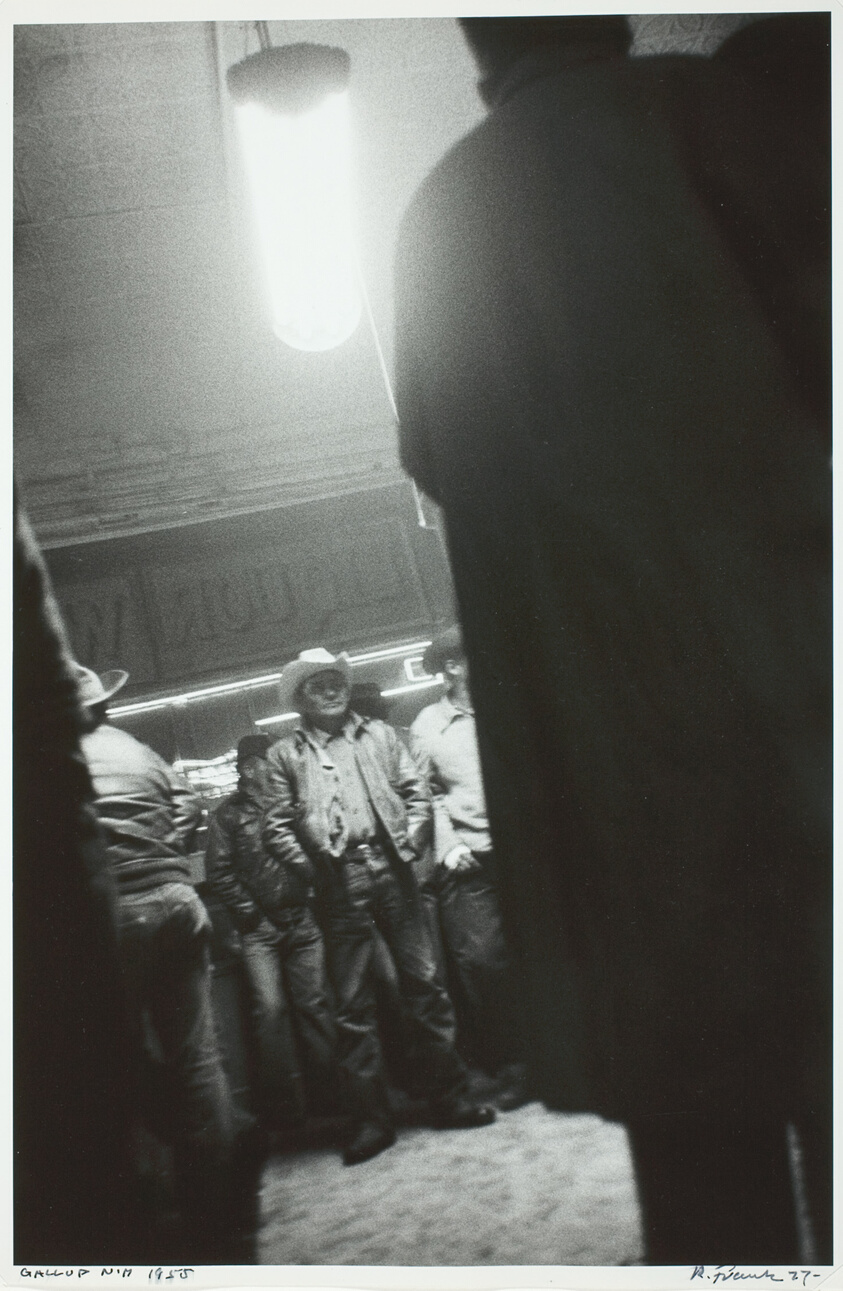

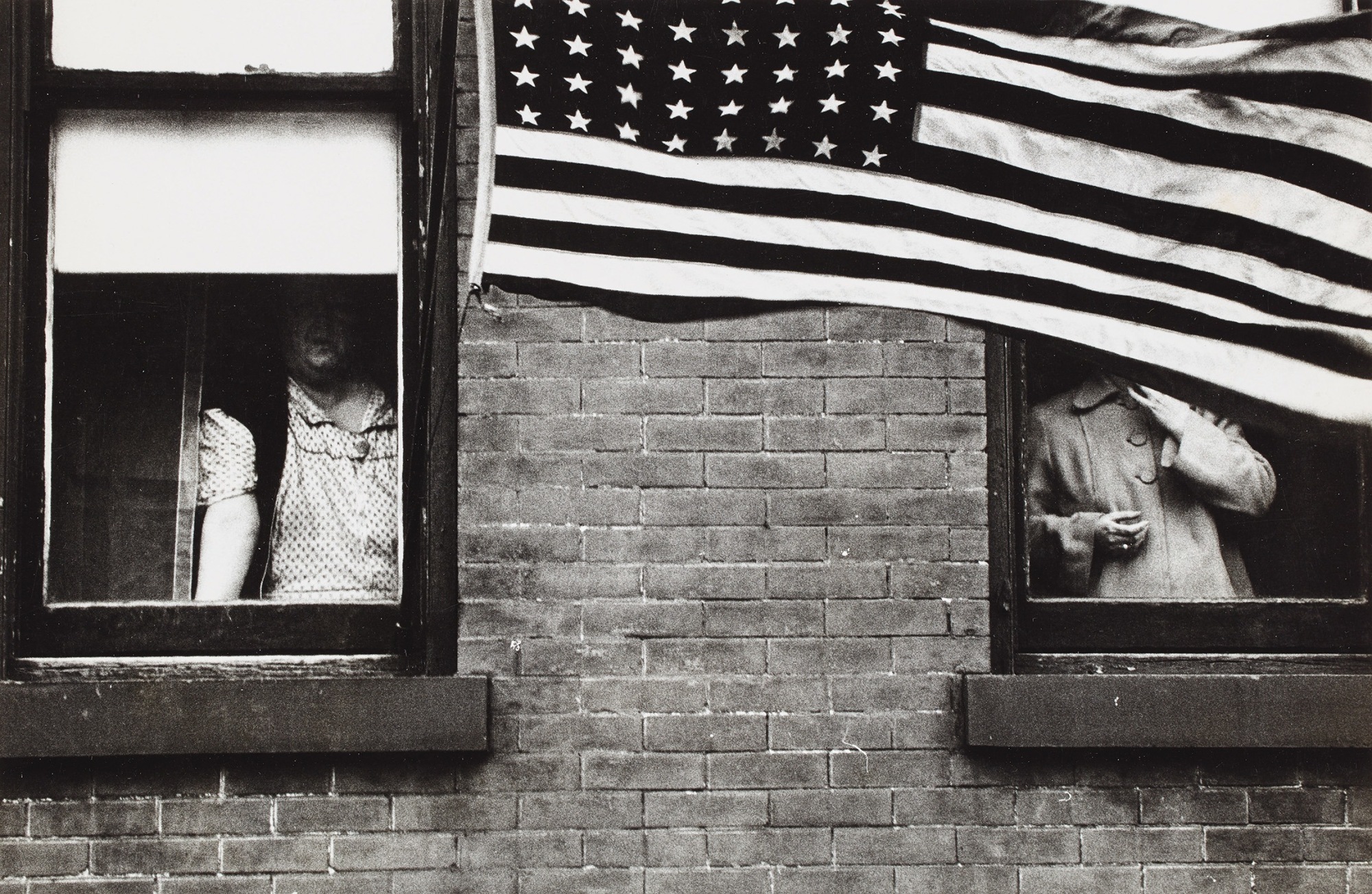

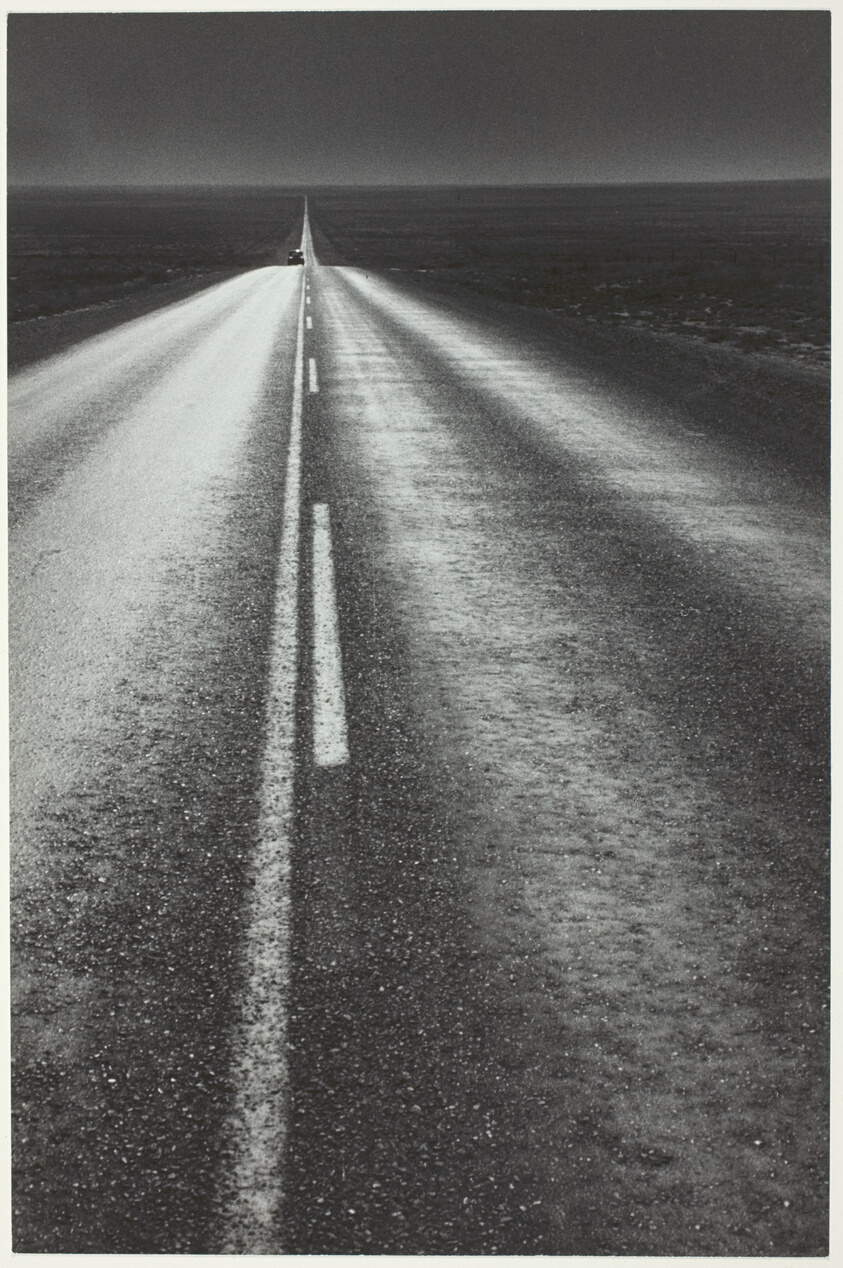

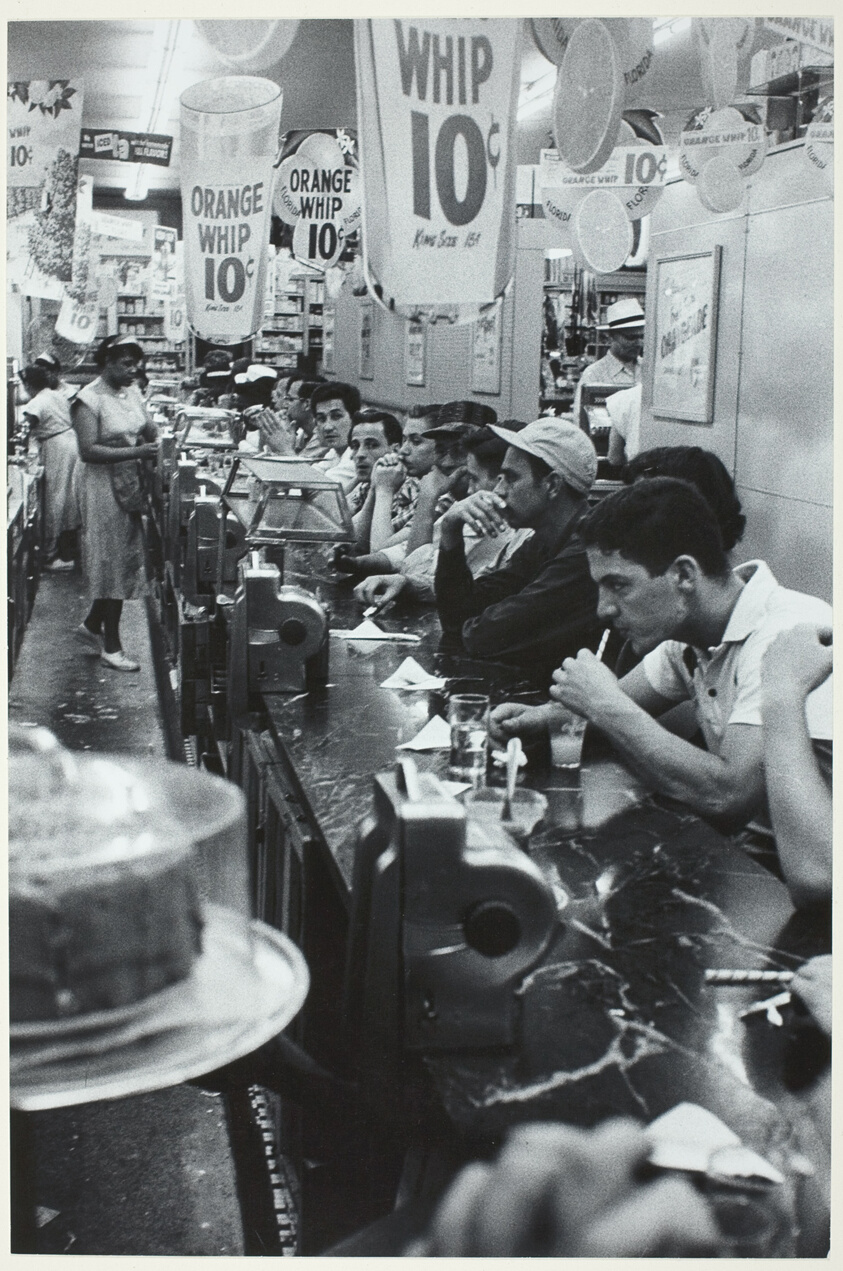

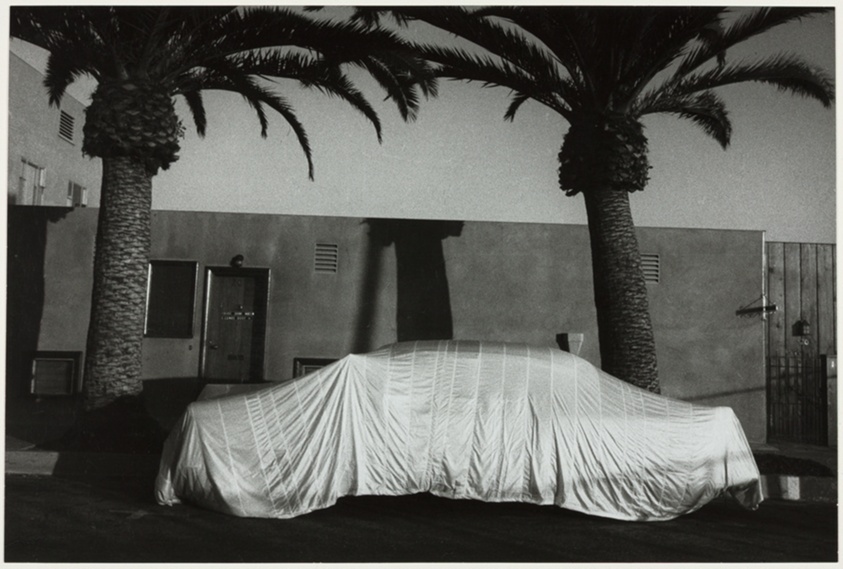

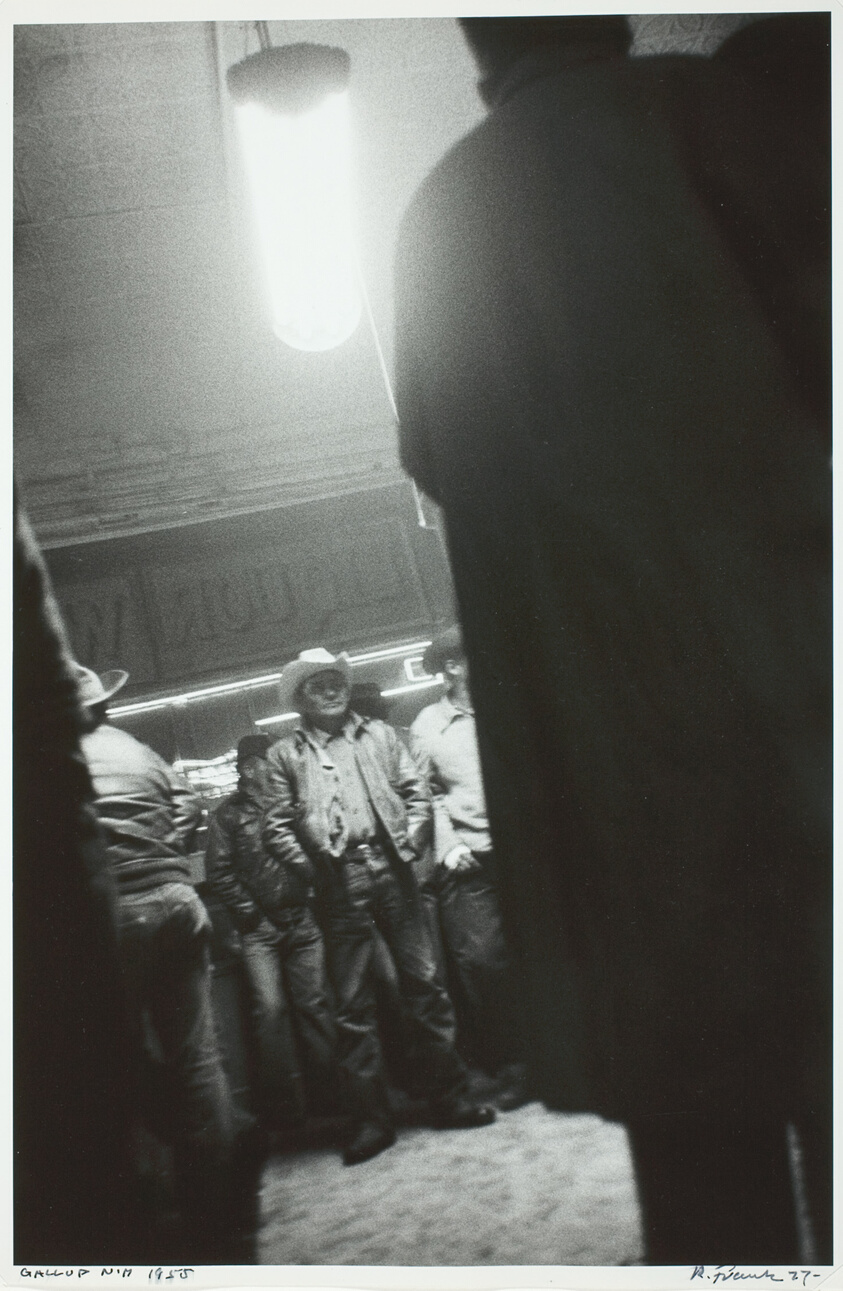

In 1955, with the support of a Guggenheim Fellowship and an introduction from Evans himself, Frank set out on a road trip across the United States that would last the better part of two years. He drove through forty-eight states, exposed over 27,000 frames of 35mm film, and subjected the country to a gaze that was simultaneously affectionate and critical, awed and disillusioned. He photographed jukeboxes and funerals, cowboys and politicians, car lots and lunch counters, crosses and flags. He photographed the segregated South with a quiet fury that needed no captions. He photographed the loneliness of the road and the strange, suspended intimacy of strangers gathered in public spaces.

From those thousands of negatives, Frank selected eighty-three photographs and sequenced them into The Americans. The book was first published in France by Robert Delpire in 1958 and then in the United States by Grove Press in 1959, with an introduction by Jack Kerouac. Its reception in America was hostile. Critics accused the pictures of being blurry, grainy, and deliberately ugly. Popular Photography ran a review that called Frank's vision warped and his technique sloppy. The photographic establishment, accustomed to the polished humanism of the Family of Man era, could not accommodate what Frank was showing them: an America that was not triumphant but melancholy, not unified but fractured along lines of race, class, and solitude.

History has reversed that initial verdict more completely than in perhaps any other case in the arts. The Americans is now regarded as the single most important photography book of the twentieth century. Its influence radiates outward in every direction. Garry Winogrand, Lee Friedlander, Diane Arbus, William Eggleston, Stephen Shore, Larry Clark, and virtually every significant photographer who came after Frank has had to reckon with the freedoms he opened up: the freedom to use blur and grain expressively, to sequence images as a personal narrative rather than a journalistic report, to acknowledge the photographer's own subjectivity as an essential part of the picture.

After The Americans, Frank largely turned away from still photography. He moved into filmmaking, producing the Beat-generation classic Pull My Daisy in 1959, narrated by Kerouac, and continuing to make experimental films and videos for the rest of his life. When he did return to the still image, it was in forms that bore little resemblance to his earlier work: collaged Polaroids, scratched and written-upon prints, deeply personal visual diaries that documented grief, memory, and the passage of time with a rawness that anticipated the confessional turn in later photography.

Personal tragedy shadowed Frank's later decades. His daughter Andrea died in a plane crash in Guatemala in 1974. His son Pablo, who struggled with mental illness, died in 1994. Frank documented his mourning with the same unflinching honesty he had brought to the American road, producing images of searing emotional directness. He withdrew increasingly from public life, spending much of his time in the remote fishing village of Mabou, Nova Scotia, where he had settled in the 1970s.

Robert Frank died in Inverness, Nova Scotia, on September 9, 2019, at the age of ninety-four. He left behind a body of work that, beginning with a single book, permanently expanded the boundaries of what photography could express. Before Frank, the photograph was expected to be a window onto the world. After Frank, it could also be a mirror, reflecting the photographer's own vision, doubt, loneliness, and love back at the viewer with an honesty that no technical perfection could match.

There is one thing the photograph must contain, the humanity of the moment. Robert Frank

Eighty-three photographs from a cross-country road trip that became the most influential photobook of the twentieth century, redefining how photography could express personal vision and national identity.

A seminal Beat-generation short film narrated by Jack Kerouac, featuring Allen Ginsberg and Gregory Corso, marking Frank's transition from still photography to the moving image.

An autobiographical visual diary combining photographs, collages, and handwritten texts that traced Frank's life from Switzerland to America to Nova Scotia with raw emotional honesty.

Born in Zürich, Switzerland, to a Jewish family of German descent. Apprentices with photographers in Basel and Zürich.

Emigrates to the United States, arriving in New York City. Begins working as a freelance photographer for fashion and editorial magazines.

Receives a Guggenheim Fellowship, sponsored by Walker Evans, and sets out on the cross-country road trip that will produce The Americans.

Les Américains published in France by Robert Delpire. The American edition follows in 1959 with an introduction by Jack Kerouac.

Directs Pull My Daisy, signalling his shift from still photography to experimental filmmaking.

Publishes The Lines of My Hand, an autobiographical visual diary. Moves to Mabou, Nova Scotia.

The National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. mounts Moving Out, a major retrospective spanning five decades.

A comprehensive new edition of The Americans, published by Steidl, coincides with the book's fiftieth anniversary.

Dies in Inverness, Nova Scotia, at the age of ninety-four. Recognised worldwide as one of the most important photographers in the history of the medium.

Have thoughts on Robert Frank's work? Share your perspective, favourite image, or how his photography has influenced your own practice.

Drop Me a Line →