Richard Avedon was born on 15 May 1923 in New York City to a Jewish family with roots in the garment trade. His father, Jacob Israel Avedon, owned a clothing store on Fifth Avenue, and the young Richard grew up surrounded by fashion, fabric, and the rhythms of commerce. His mother, Anna, kept elegant photo albums that fascinated the boy, and his cousin, the model Margie Lederer, provided an early glimpse of the relationship between beauty and the camera. From childhood, Avedon was drawn to the photograph as an object — something that could fix a moment of grace or vanity and hold it still for examination.

During the Second World War, Avedon served in the United States Merchant Marine, where he was assigned the task of taking identification photographs of the crew. It was unglamorous work — head-on portraits against plain backgrounds, faces stripped of context — but it planted the seed of everything that would follow. After the war, he enrolled at the New School for Social Research in New York, where he studied under the legendary art director Alexey Brodovitch, the man who was reshaping the visual language of Harper’s Bazaar. Brodovitch recognised Avedon’s talent immediately. By the age of twenty-two, Avedon had been hired as a staff photographer at Harper’s Bazaar, beginning a partnership with Brodovitch that would transform fashion photography.

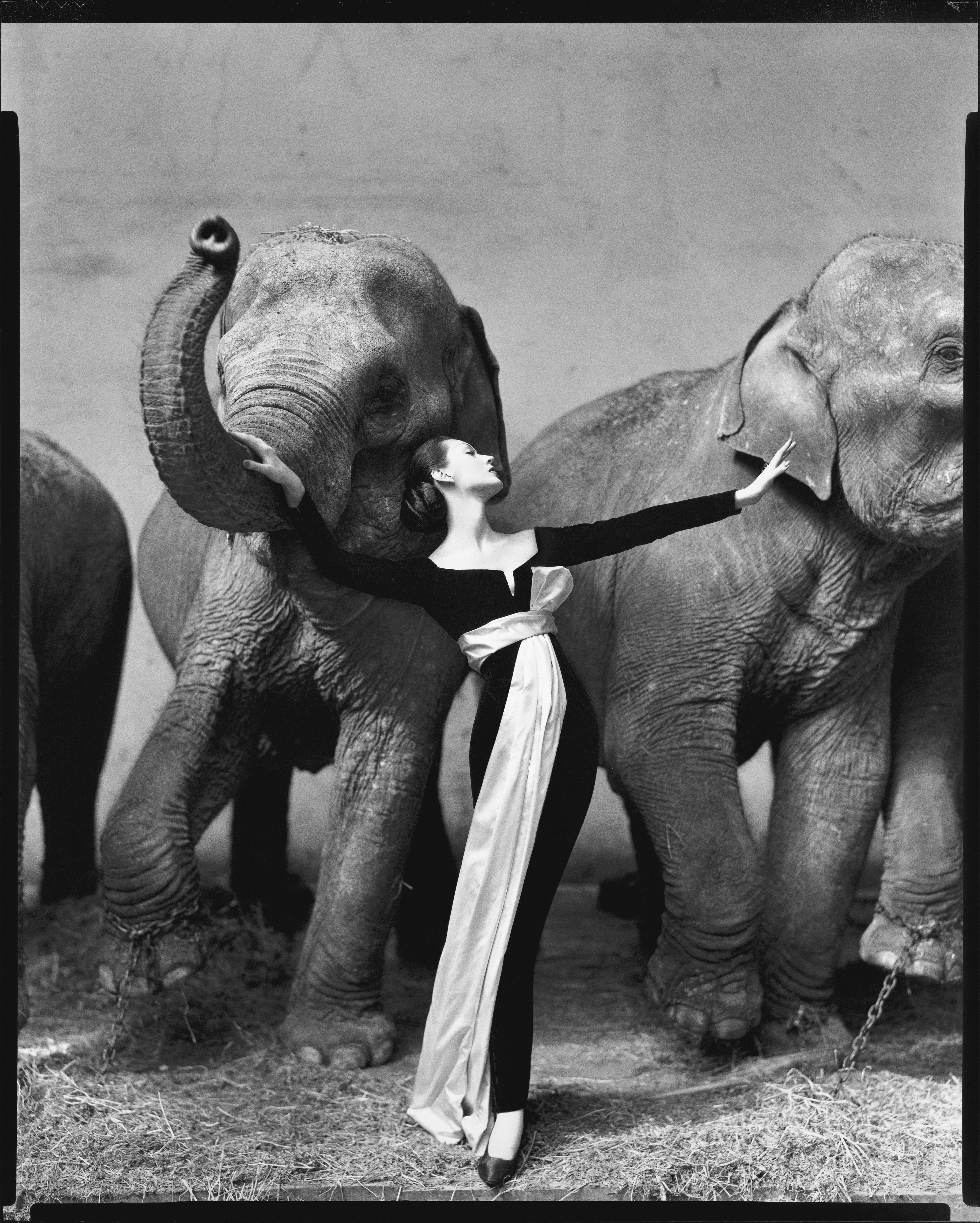

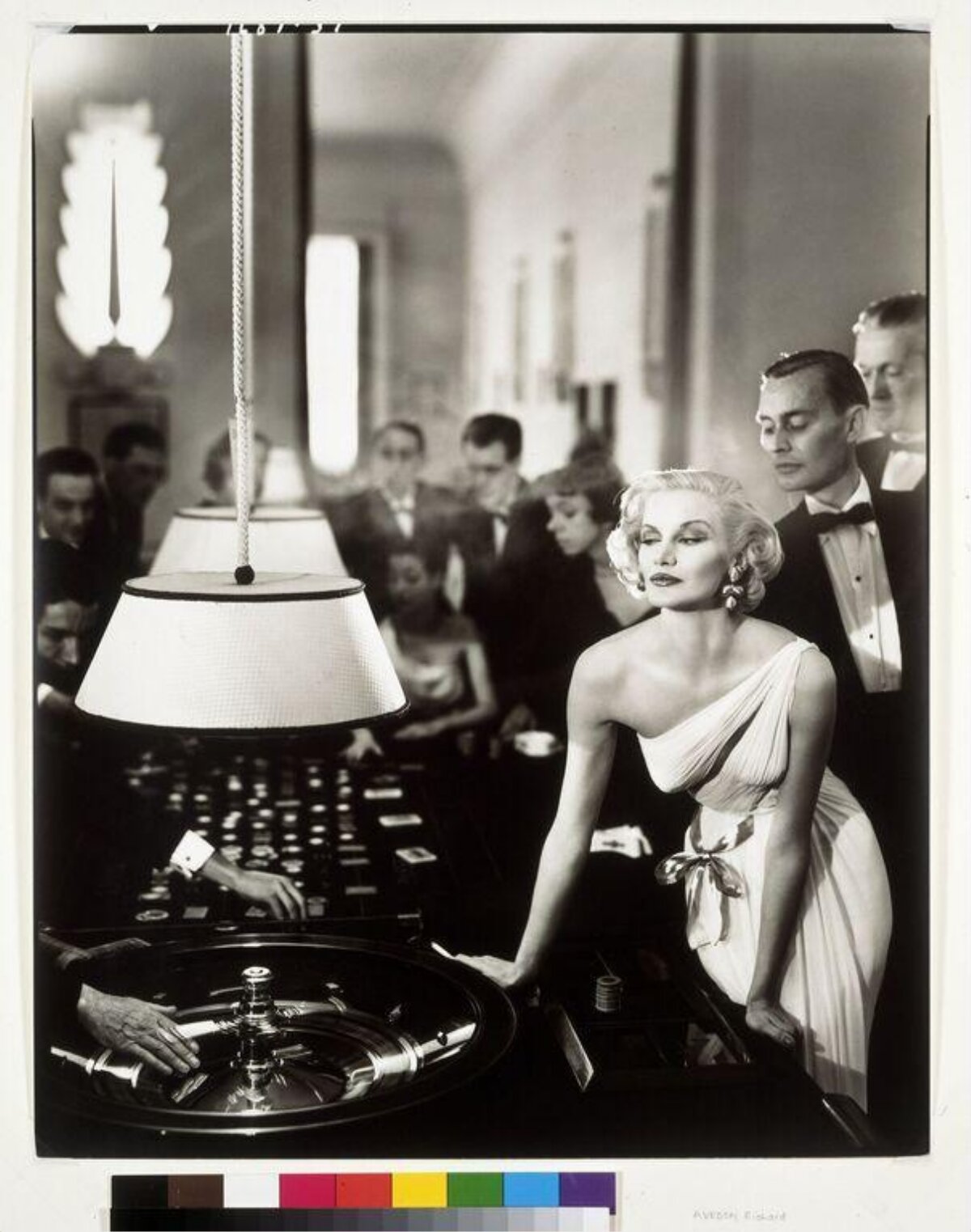

What Avedon did at Harper’s Bazaar in the late 1940s and 1950s was revolutionary. Where fashion photography had been static and posed — models standing rigidly in studios, faces arranged into masks of elegant composure — Avedon brought movement, spontaneity, and life. He took his models out of the studio and into the streets of Paris, into nightclubs, cafés, circuses, and racing tracks. They laughed, ran, danced, ate, hailed taxis, and leapt in the air. His photographs crackled with energy and narrative. The clothes were still the subject, but now they existed on bodies in motion, animated by personality and joy. Fashion, in Avedon’s hands, became dynamic and alive.

The most famous of these early images is Dovima with Elephants, made at the Cirque d’Hiver in Paris in 1955. The model Dovima, wearing a black-and-white Dior evening gown by Yves Saint Laurent, stands with her arms extended between two enormous circus elephants, her body a slender diagonal of elegance against their massive, rough-skinned forms. The image distils everything that defined Avedon’s genius: the drama of juxtaposition, the grace of the human body, the sense that fashion is not merely about clothes but about the theatre of being alive. It remains, seven decades later, perhaps the most famous fashion photograph ever made.

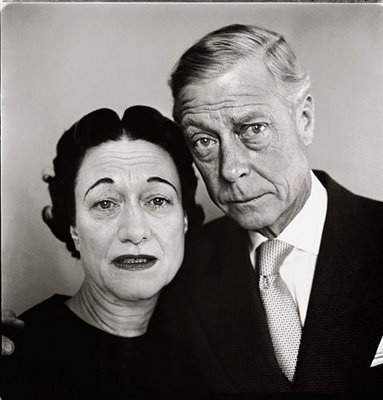

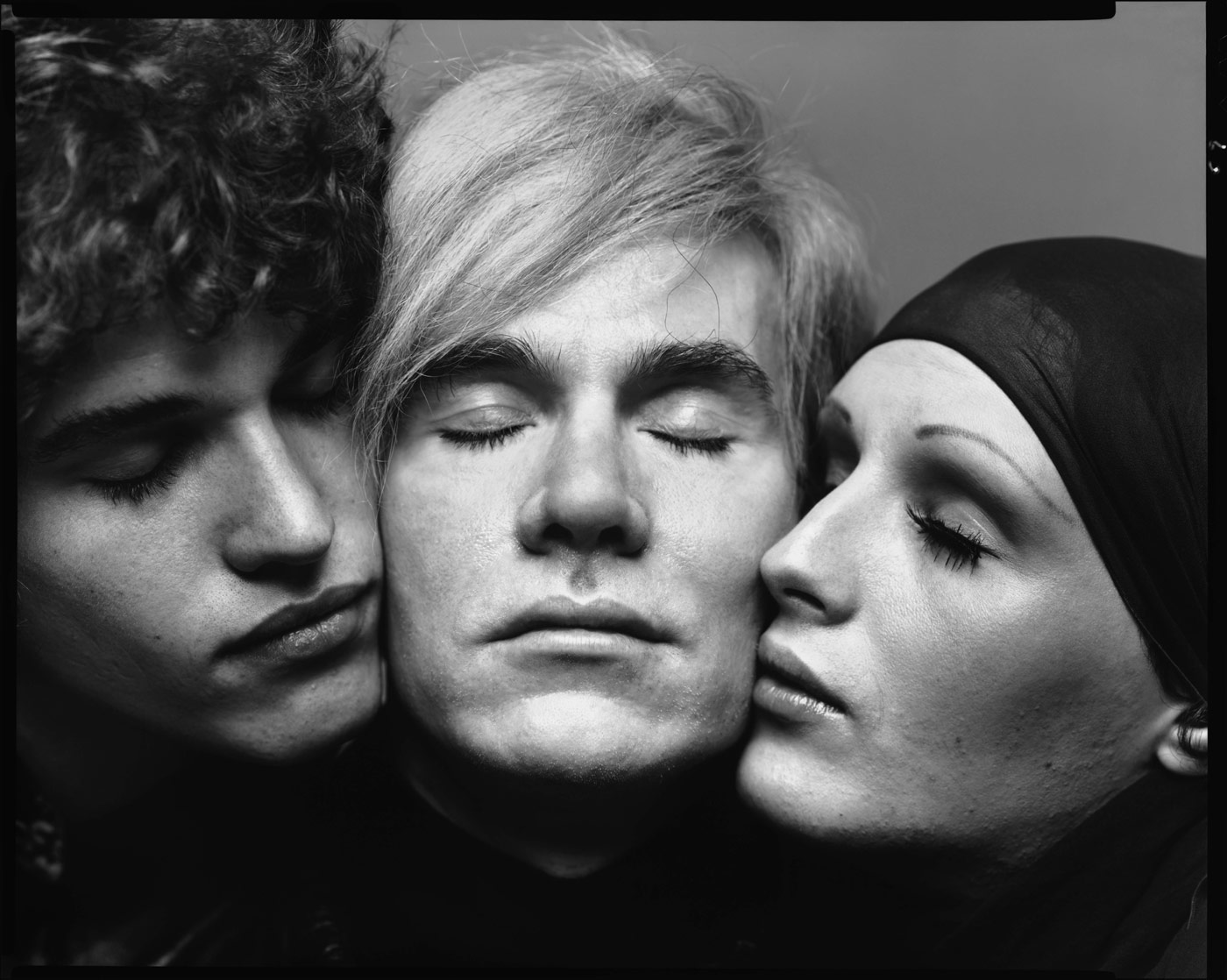

Alongside his fashion work, Avedon developed a parallel practice in portraiture that would prove equally influential. Beginning in the 1950s, he began making large-format, close-up portraits of artists, writers, politicians, and cultural figures, shot against a plain white background with a large-format camera. These portraits were unflinching. Avedon stripped away every prop, every backdrop, every element of context, leaving nothing but the face, the body, and the merciless clarity of the lens. The white background became his signature — a void that forced the viewer to confront the subject directly, without the comfort of narrative or setting. His portraits of Marilyn Monroe, the Duke and Duchess of Windsor, Dwight D. Eisenhower, Andy Warhol, and countless others revealed vulnerability, age, weariness, and humanity beneath the public masks.

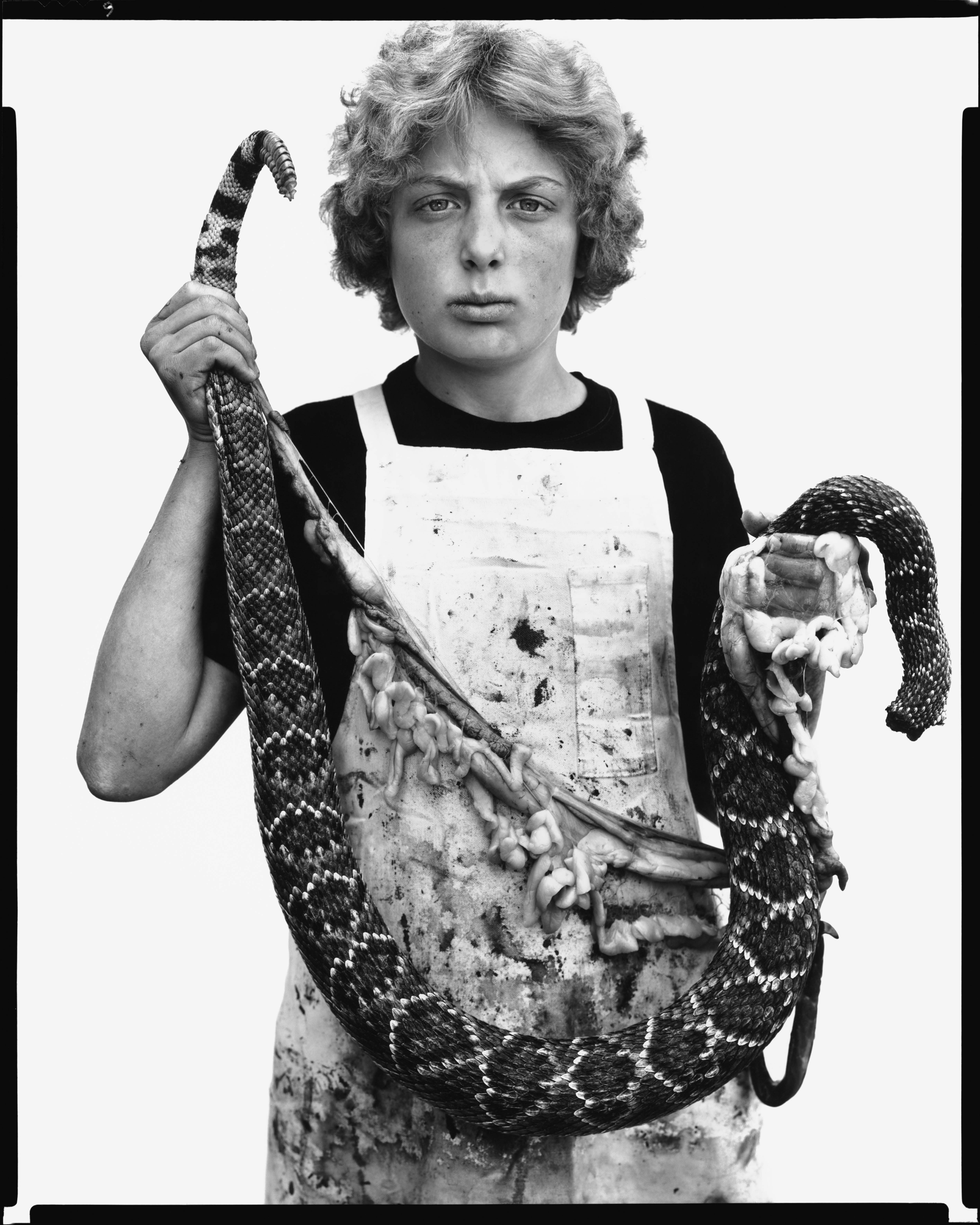

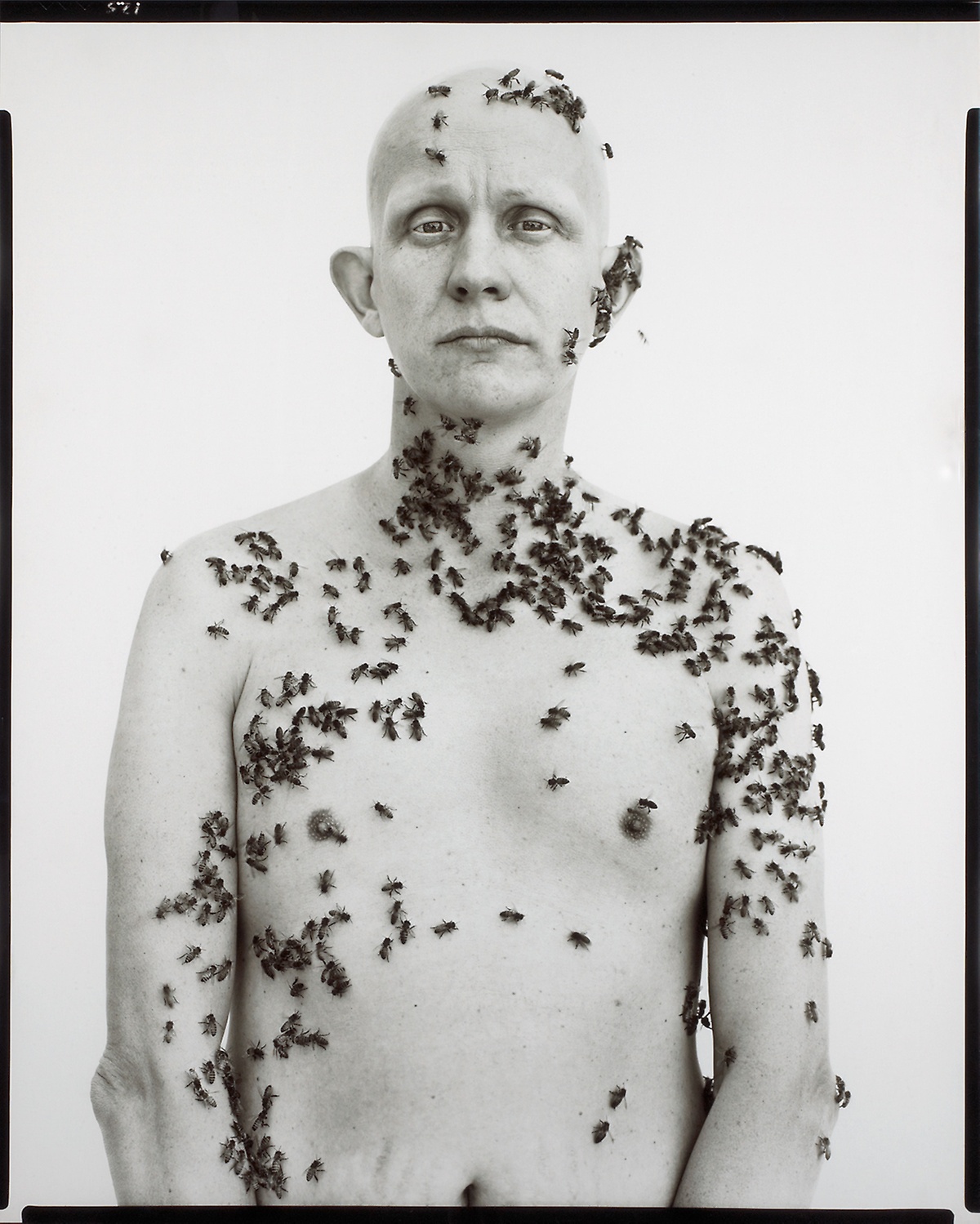

In 1979, Avedon embarked on what would become the most ambitious and controversial project of his career: In the American West. Over five years, he travelled across the western United States photographing not celebrities or models but blue-collar workers, ranchers, oil-field hands, slaughterhouse employees, drifters, and teenagers. He used the same white-background technique he had perfected in his celebrity portraiture, setting up a portable studio in small towns across Texas, Montana, Wyoming, and Colorado. The resulting portraits — of figures like Boyd Fortin, a thirteen-year-old rattlesnake skinner from Sweetwater, Texas, and Ronald Fischer, a beekeeper covered in bees from Davis, California — were images of devastating intimacy and dignity. When the project was published in 1985, it provoked fierce debate: some critics accused Avedon of aestheticising poverty and exploiting his subjects, while others hailed the work as a radical expansion of the photographic portrait. It remains one of the landmark bodies of work in twentieth-century photography.

In 1992, Avedon was appointed the first staff photographer for The New Yorker, a role that allowed him to combine his portraiture and editorial instincts in new ways. He produced portraits of political figures, photo-essays on social themes, and fashion work that continued to push boundaries well into his seventies. His energy and curiosity were undiminished. He remained a restless innovator, constantly seeking new subjects and new approaches, unwilling to rest on the extraordinary body of work he had already created.

Avedon died on 1 October 2004 of a cerebral haemorrhage in San Antonio, Texas, while on assignment for The New Yorker — still working, still photographing, at the age of eighty-one. The Richard Avedon Foundation was established to preserve his legacy and archive. His influence on photography is immeasurable: he proved that fashion photography could be art, that portraiture could be both brutal and compassionate, and that the white wall and the human face were all a great photographer needed to reveal the truth about another person.