Lucybelle Crater and Close Friend

From The Family Album of Lucybelle Crater, c. 1970

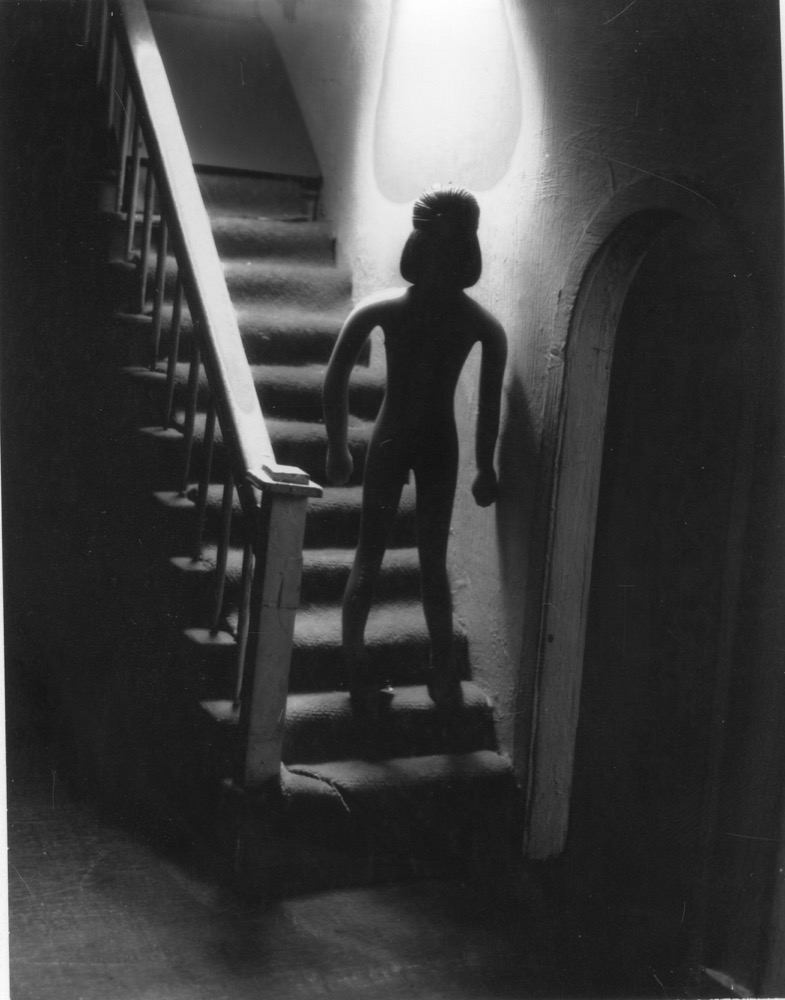

Romance (N.) from Ambrose Bierce #3

c. 1964

Child with Mask in Doorway

c. 1963

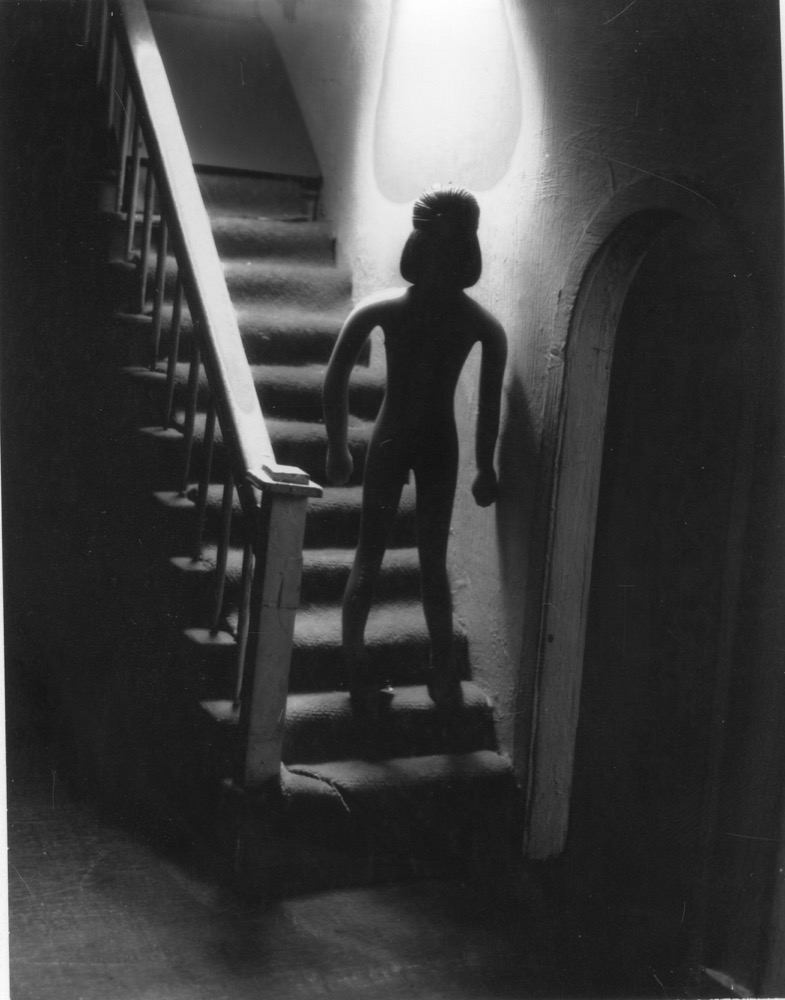

Motion Study, Abandoned House

c. 1965

An optician from Lexington, Kentucky, whose haunting photographs of masked figures, blurred motion, and abandoned interiors created a body of work that stands among the most mysterious and original in the history of American photography.

1925, Normal, Illinois – 1972, Lexington, Kentucky — American

Lucybelle Crater and Close Friend

From The Family Album of Lucybelle Crater, c. 1970

Romance (N.) from Ambrose Bierce #3

c. 1964

Child with Mask in Doorway

c. 1963

Motion Study, Abandoned House

c. 1965

Ralph Eugene Meatyard was born in 1925 in Normal, Illinois, a small college town whose name would prove ironically apt for an artist whose life's work was devoted to exploring the uncanny spaces between the normal and the strange. He showed no particular artistic inclination as a young man, serving in the United States Navy during the Second World War and then settling into a career as a licensed optician in Lexington, Kentucky, where he and his wife Madelyn raised three children. It was in 1950, when he purchased a camera to photograph his newborn son, that Meatyard discovered the medium that would consume the remaining twenty-two years of his life. He enrolled in a photography course at the Lexington Camera Club, where he studied with Van Deren Coke, a photographer and educator who recognised Meatyard's unusual talent and encouraged him to pursue his vision wherever it might lead.

From the very beginning, Meatyard's photographs were unlike anything being produced in American photography at the time. While his contemporaries in the documentary tradition were photographing the social landscape with increasing precision and objectivity, Meatyard was drawn to the interior landscape of the psyche — to dreams, fears, and the uncanny. His earliest significant works featured masks: cheap Halloween masks and rubber monster faces worn by his children, his wife, and his friends, posed in the abandoned houses and overgrown lots that dotted the Kentucky countryside. The masks simultaneously concealed and revealed, stripping away the social identities of his subjects while exposing something more primitive and disturbing beneath. A child in a grotesque mask standing in a doorway; a figure in a suit wearing the face of an old man; two masked figures embracing in a room of peeling wallpaper — these images had the quality of waking nightmares, domestic scenes invaded by the uncanny.

Meatyard was deeply influenced by the literature and philosophy he read voraciously throughout his life. He was a close friend of the writer Wendell Berry and the monk and author Thomas Merton, both of whom lived in the Lexington area and shared his interest in the relationship between the spiritual and the material. He read widely in Zen Buddhism, the German Romantics, the fiction of Flannery O'Connor, and the sardonic writings of Ambrose Bierce, whose The Devil's Dictionary provided the titles and conceptual framework for an entire series of photographs. This literary and philosophical grounding gave Meatyard's work a density of reference that set it apart from the more intuitive approaches of most art photographers.

In the mid-1960s, Meatyard began producing what he called his No-Focus images — photographs in which the entire frame was deliberately thrown out of focus, reducing the visible world to a field of soft, luminous shapes. Trees became ghostly presences, figures dissolved into light, and the familiar world was rendered as a realm of pure visual sensation. These images anticipated the concerns of much later photographic practice, particularly the renewed interest in abstraction and materiality that emerged in the 2000s. They also reflected Meatyard's deep engagement with Zen Buddhism and its emphasis on the dissolution of the ego and the illusory nature of fixed forms.

The crowning achievement of Meatyard's career, and the work for which he is best known, is The Family Album of Lucybelle Crater, produced in the last years of his life. The project consists of sixty-four photographs, each depicting two figures: one is always Meatyard's wife Madelyn, wearing the same transparent old-woman mask, and the other is a different friend or family member, each wearing an identical grotesque rubber mask. Every image is titled in the same format: "Lucybelle Crater and [relationship]." The effect is simultaneously comic and deeply unsettling — a family album in which every face is hidden, every identity obscured, and the conventional genres of domestic photography are turned inside out. The work has been read as a meditation on identity and its dissolution, on the masks we all wear in social life, and on the relationship between the public self and the unknowable interior.

Meatyard continued to work as an optician throughout his photographic career, and there is a poignant irony in the fact that a man whose profession was the correction of vision spent his artistic life exploring the limits and distortions of seeing. He died of cancer in 1972, at the age of forty-six, having never achieved widespread recognition. His work was known and admired by a small circle of friends and fellow photographers, including Minor White, Aaron Siskind, and Henry Holmes Smith, but the broader art world had not yet caught up with the strangeness of his vision.

The decades since his death have brought a steady and deepening recognition of Meatyard's achievement. The Family Album of Lucybelle Crater was published posthumously in 1974 and is now regarded as one of the most original photobooks of the twentieth century. Major exhibitions at the International Center of Photography in New York and museums across America and Europe have established him as a singular figure in the history of the medium — a photographer who, working in isolation from the New York art world, produced a body of work that anticipated conceptual photography, challenged the conventions of the family snapshot, and demonstrated that the camera could be an instrument not only for recording the visible world but for exploring the invisible territories of the imagination.

Meatyard's legacy is one of radical independence. He proved that a photographer need not be based in a major cultural centre, need not work within established traditions, and need not pursue commercial success to produce work of lasting significance. His photographs remain as unsettling and mysterious today as they were when he made them, and they continue to reward the kind of sustained, contemplative attention that Meatyard himself brought to everything he saw.

No photograph is ever truly honest. The camera always lies. It is up to the photographer to determine the nature of its deceit. Ralph Eugene Meatyard

Sixty-four photographs of masked figures in which Meatyard's wife always wears the same mask while posing with differently masked friends and family, creating a profoundly strange alternative family album.

A series of deliberately unfocused photographs in which the visible world dissolves into fields of luminous abstraction, reflecting Meatyard's engagement with Zen Buddhism and the nature of perception.

A series of photographs inspired by Ambrose Bierce's sardonic writings, combining masked figures and abandoned interiors to create images of darkly comic menace and literary allusion.

Born in Normal, Illinois. Serves in the US Navy during the Second World War before settling in Lexington, Kentucky.

Purchases his first camera to photograph his newborn son, and soon enrols in a photography course at the Lexington Camera Club under Van Deren Coke.

Begins producing his mask photographs, using cheap Halloween masks to transform family and friends into uncanny presences in abandoned settings.

Creates the Ambrose Bierce series, drawing on literary sources to deepen the conceptual dimensions of his photographic practice.

Begins his No-Focus series, deliberately throwing the entire frame out of focus to explore perception, abstraction, and Zen philosophy.

Starts work on The Family Album of Lucybelle Crater, his most ambitious and celebrated project, which would occupy the final years of his life.

Befriends Thomas Merton and Wendell Berry in the Lexington area, sharing intellectual and spiritual interests that enrich his photographic vision.

Dies of cancer in Lexington, Kentucky, at the age of forty-six. The Family Album of Lucybelle Crater is published posthumously in 1974.

Interested in discussing photography, collaboration, or just want to say hello? I’d love to hear from you.

Contact →