Paul Strand was born in 1890 in New York City, the son of Bohemian immigrants who had settled on the Upper West Side. His life in photography began at the Ethical Culture Fieldston School, where at the age of seventeen he enrolled in a class taught by the documentary photographer Lewis Hine. Hine introduced Strand not only to the mechanics of the camera but to the idea that photography could serve as an instrument of social conscience, a tool for revealing truths about the human condition that might otherwise remain invisible. Hine also took his students to visit Alfred Stieglitz's gallery at 291 Fifth Avenue, where Strand encountered for the first time the work of the European avant-garde alongside photographs by Stieglitz, Edward Steichen, and others. The experience was transformative. Strand understood immediately that photography was not merely a means of recording the world but a medium capable of expressing the deepest perceptions of the individual artist.

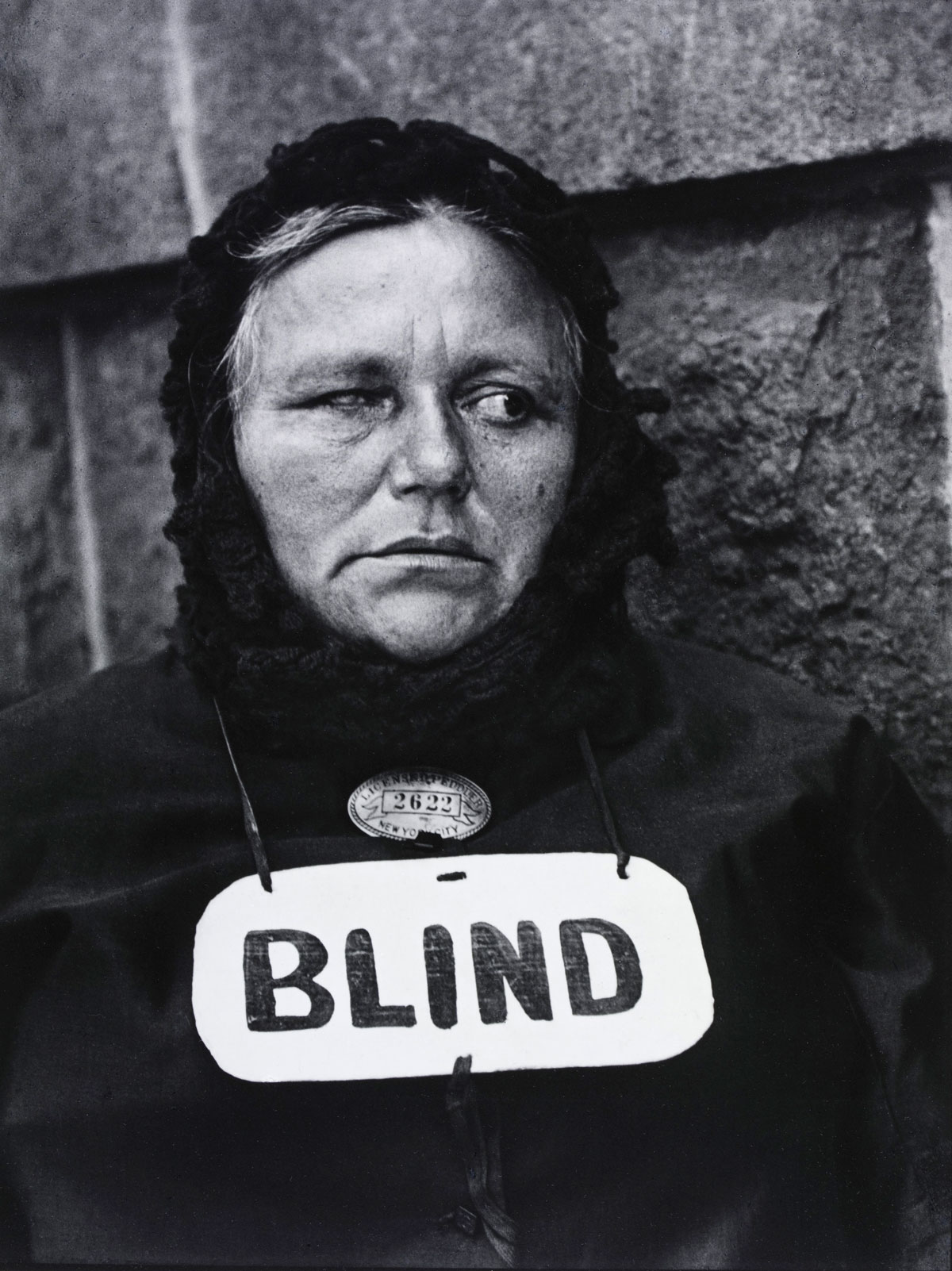

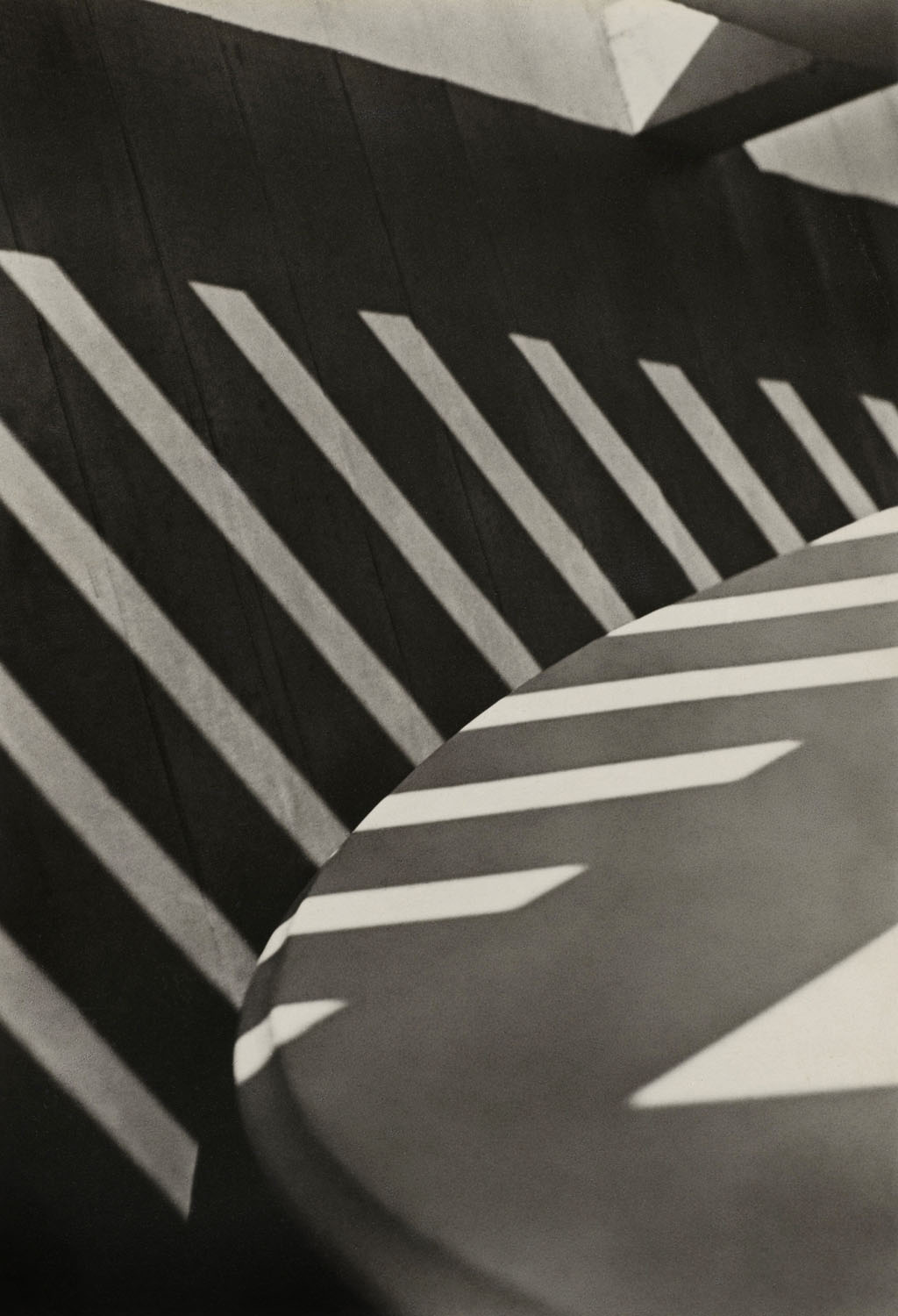

Between 1915 and 1917, Strand produced a body of work that effectively inaugurated modernist photography. His candid street portraits, made with a camera fitted with a false lens so that his subjects did not know they were being photographed, captured the faces of New York's working poor with a directness and dignity that had no precedent. Blind Woman, New York (1916), showing a woman wearing a sign around her neck, remains one of the most iconic photographs of the twentieth century. Simultaneously, Strand was producing abstract studies — close-ups of bowls, porch shadows, and picket fences — that explored the formal properties of light, line, and texture with a rigour that paralleled the experiments of the cubist painters he admired.

Stieglitz recognised Strand's genius immediately. In 1916, he devoted the final two issues of his journal Camera Work to Strand's photographs, declaring them the beginning of a new era in the medium. Stieglitz wrote that Strand's work was the expression of a new vision, one that rejected the soft-focus romanticism of pictorialism in favour of what would come to be called straight photography — sharp, precisely exposed, and honest in its engagement with the material world. This endorsement placed Strand at the centre of the American photographic avant-garde and established the principles that would guide his work for the next six decades.

Through the 1920s, Strand turned increasingly to the machine as a subject, producing studies of automobile wheels, movie cameras, and industrial lathes that celebrated the beauty of mechanical precision. He also began working in film, collaborating with the painter Charles Sheeler on Manhatta (1921), a short avant-garde film celebrating the dynamism of New York City that is now regarded as a landmark of early American cinema. Strand would continue to make films throughout his career, including The Wave (1936), shot in Mexico, and Native Land (1942), a documentary about civil liberties in America.

In 1932, Strand travelled to Mexico at the invitation of the composer Carlos Chávez, serving as chief of photography and cinematography for the Mexican government's Department of Fine Arts. The Mexican experience deepened Strand's commitment to social documentary and to the idea of photography as a collaborative engagement between the photographer and the communities he depicted. His Mexican portraits and landscapes, published years later in The Mexican Portfolio (1940), demonstrated a new warmth and empathy in his work without sacrificing any of his formal precision.

The late 1940s and 1950s marked a period of profound change in Strand's life. Increasingly at odds with the political climate of Cold War America — he had been a committed leftist throughout his career, involved with the Photo League and other progressive organisations — Strand left the United States in 1950 and settled permanently in France. From his home in Orgeval, outside Paris, he embarked on a series of collaborative books that combined his photographs with texts by local writers, each devoted to a particular place and its people: La France de profil (1952), Un Paese (1955, on an Italian village), Tir a'Mhurain (1962, on the Outer Hebrides), Living Egypt (1969), and Ghana: An African Portrait (1976).

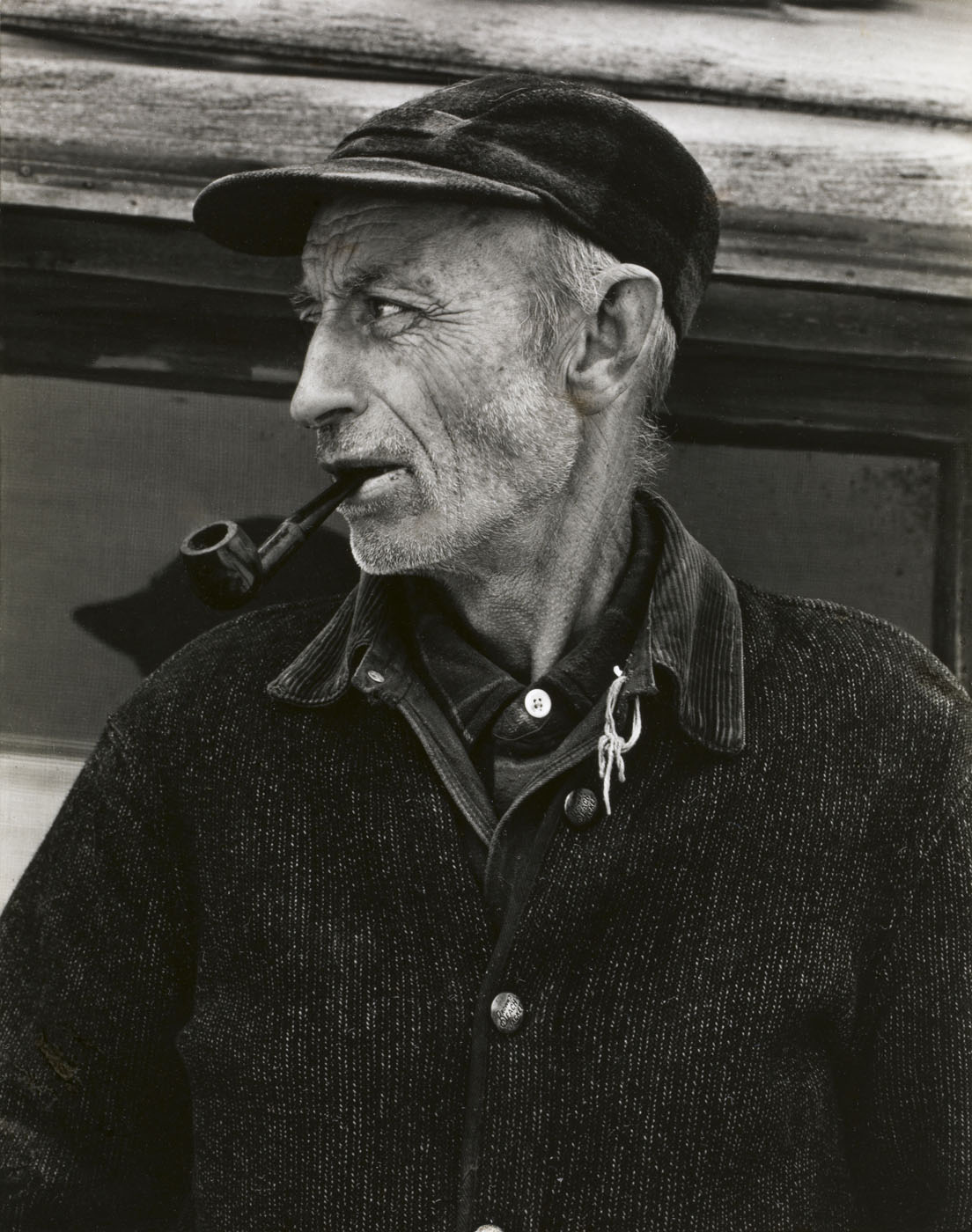

These late books represent some of the most fully realised achievements in the history of the photobook. In each, Strand sought to render the spirit of a place through the accumulation of portraits, landscapes, and details — a door handle, a stone wall, the texture of a ploughed field — that together compose a portrait of a community and its relationship to the land. The portraits, always made with the knowledge and cooperation of the subject, possess a gravity and stillness that recall the great portrait traditions of painting. Strand insisted on using a large-format camera, setting it up on a tripod and engaging his subjects in conversation before making the exposure, so that each portrait was the product of a relationship, however brief, between photographer and subject.

Paul Strand died in Orgeval in 1976, one of the most honoured photographers in the history of the medium. His influence is incalculable. He demonstrated that photography could be simultaneously an art form and a social practice, that formal beauty and political engagement were not opposites but allies, and that the camera, wielded with intelligence and moral seriousness, could reveal not just the appearance of the world but its underlying structure and meaning. From Ansel Adams to Edward Weston, from the social documentarians of the Photo League to the conceptual artists of the late twentieth century, virtually every significant strand of American photography can trace a line back to Paul Strand.