Laurie in Ward 81, Oregon State Hospital

1976

Streetwise (Runaway Girls), Seattle

1983

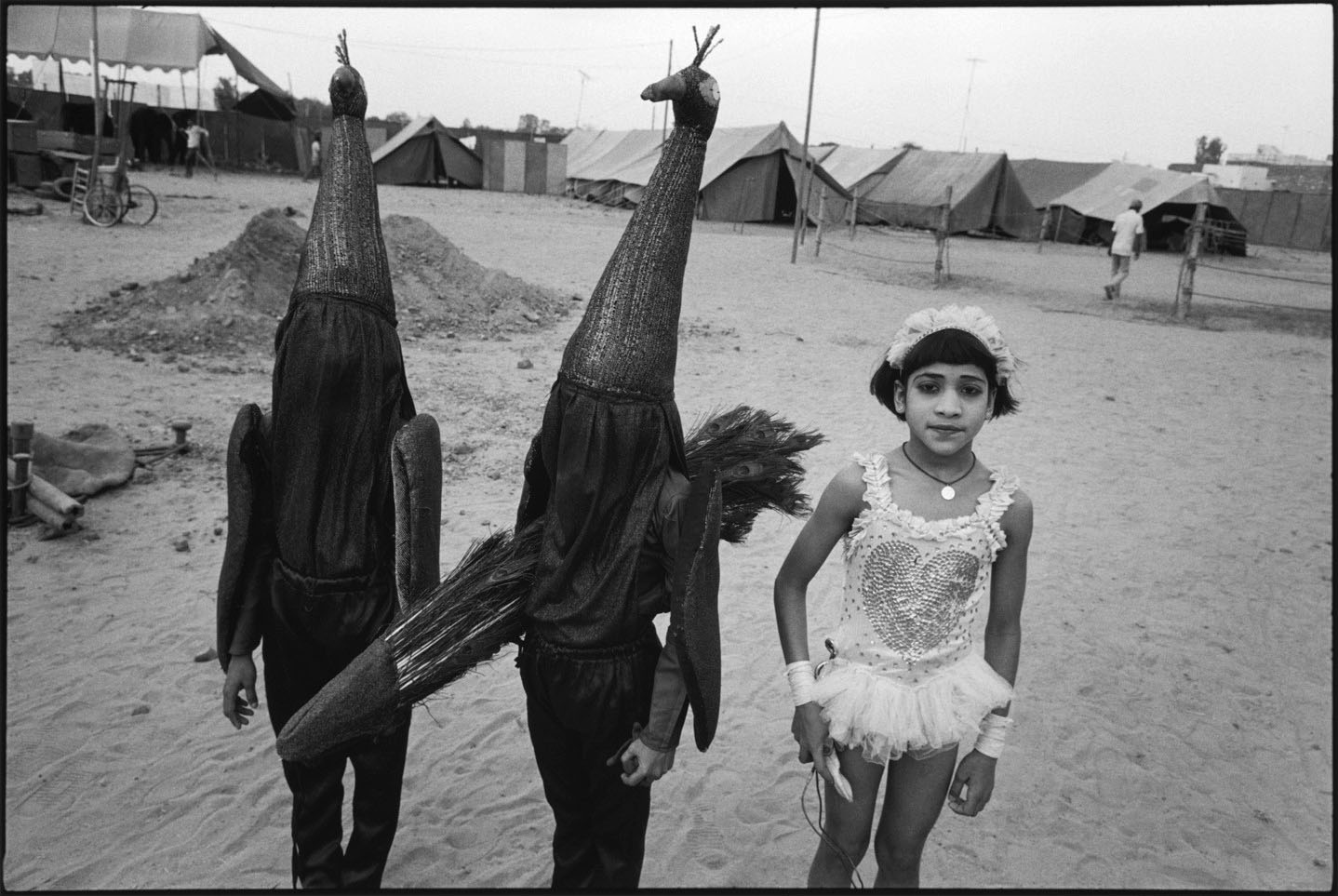

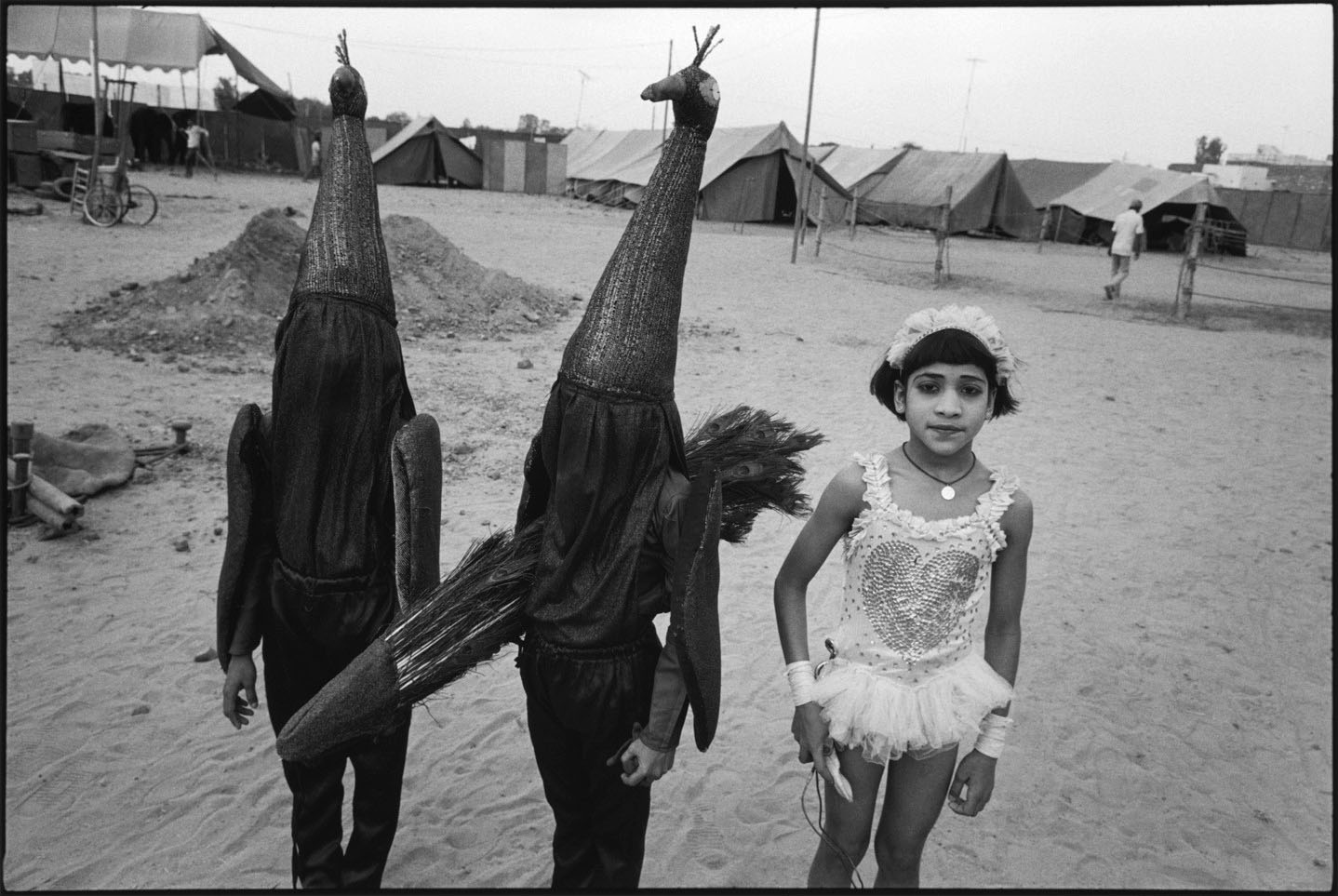

Indian Circus (Child Acrobat), India

1989

Twins, Twinsburg, Ohio

1998

Falkland Road, Bombay

1978

Compassionate documentarian of society's margins, whose deeply immersive portraits of runaway children, circus performers, prostitutes, and psychiatric patients revealed the dignity and complexity of lives most photographers would never see.

1940, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania – 2015, New York City — American

Laurie in Ward 81, Oregon State Hospital

1976

Streetwise (Runaway Girls), Seattle

1983

Indian Circus (Child Acrobat), India

1989

Twins, Twinsburg, Ohio

1998

Falkland Road, Bombay

1978

Mary Ellen Mark was born on March 20, 1940, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, into a middle-class family with deep roots in the city. From an early age she showed an instinct for visual storytelling, drawn to painting and drawing before discovering the camera as a teenager. She studied painting and art history at the University of Pennsylvania, where a growing fascination with the photographic image began to eclipse her work on canvas. It was a shift that would define her life: the realisation that the world as it existed — raw, unvarnished, and profoundly human — was more compelling than anything she could invent.

After completing her undergraduate degree, Mark enrolled in the Annenberg School for Communication at the University of Pennsylvania, earning an MFA in photojournalism in 1964. The programme sharpened her technical skills and confirmed her commitment to documentary work, but it was a Fulbright scholarship in 1965 that truly set her course. She travelled to Turkey to photograph, and the experience of immersing herself in an unfamiliar culture — of learning to see by living alongside her subjects rather than merely observing them — became the foundation of her entire practice. She would spend the rest of her career refining this method: not the drive-by shooting of the photojournalist on deadline, but weeks and months of patient, embedded presence.

That method found its most powerful early expression in Ward 81. In 1976, Mark arranged to live for thirty-six days inside the women’s secure ward of the Oregon State Hospital, sleeping among the patients, eating with them, sharing their daily routines. The portraits she made there are among the most extraordinary in documentary photography — images of women trapped in institutional confinement that refuse to reduce their subjects to objects of pity or spectacle. Instead, Mark found individuality, dignity, and even beauty in the ward’s harsh fluorescent light. The resulting book, Ward 81, published in 1979, established her reputation as a photographer willing to go where others would not, and to stay long enough to earn the trust that makes genuine intimacy possible.

Two years later, she pushed even further. In 1978, Mark travelled to Bombay and spent three months living among the sex workers of Falkland Road, one of the city’s most notorious red-light districts. At first she was met with hostility — the women threw garbage and water at her, suspicious of her motives. But she persisted, returning day after day, until they accepted her presence and allowed her into their rooms, their rituals, their lives. The photographs she made there, published as Falkland Road in 1981, are remarkable for their absence of judgement. Mark photographed prostitutes, madams, and clients with the same unflinching directness, creating a body of work that is at once devastating and deeply humane.

Her most celebrated project began in 1983, when Mark started photographing runaway and homeless teenagers on the streets of Seattle. She centred her work on a girl called Tiny, a thirteen-year-old streetwalker whose fierce vulnerability became the emotional heart of the series. The project produced the landmark photobook Streetwise, published in 1988, and an Academy Award-nominated documentary film of the same name, directed by her husband Martin Bell. Mark’s portraits of Tiny, Rat, Mike, and the other children are neither sentimental nor exploitative; they meet their subjects at eye level, acknowledging both the danger of their circumstances and the stubborn vitality with which they navigated them. Mark would return to photograph Tiny over the following three decades, documenting her passage from adolescence through motherhood in a sustained act of artistic commitment that has few parallels in the medium.

Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, Mark continued to seek out communities on the margins. Her Indian Circus project, published in 1989, captured the surreal and luminous world of travelling circus performers and their families across India — acrobats, animal trainers, and child performers living in a realm that seemed suspended between magic and poverty. She photographed Mother Teresa in Calcutta, homeless families in America, and identical twins at the annual Twins Days Festival in Twinsburg, Ohio. Her magazine work for Life, Rolling Stone, Vanity Fair, and The New Yorker brought her images to millions, yet she never lost the patience and depth that distinguished her personal projects from conventional editorial assignments.

What set Mark apart from her contemporaries was not simply her choice of subject but her method and her moral clarity. She was unflinching but never cruel, direct but never exploitative. She believed that honest engagement with her subjects — telling them exactly who she was and what she intended — was both an ethical obligation and the only way to make photographs that told the truth. Her images do not sentimentalise poverty or suffering; nor do they aestheticise it. They simply insist on the full humanity of people whom the wider world preferred not to see, and in doing so they challenged viewers to reckon with their own assumptions about who deserved to be looked at and how.

Mary Ellen Mark died on May 25, 2015, in New York City, at the age of seventy-five. By then she had published eighteen books, received countless awards including the Outstanding Contribution to Photography Award from the World Photography Organisation, and was recognised as one of the most important documentary photographers in American history. Her legacy endures not only in the images she left behind but in the example she set: that the photographer’s deepest responsibility is not to the frame or the light but to the people who stand before the lens, and that the only way to honour that responsibility is to be present — fully, patiently, and with an open heart.

I just think it is important to be direct and honest with people about why you are photographing them and what you are doing. After all, you are taking some of their soul. Mary Ellen Mark

A devastating series of portraits made during thirty-six days living in the women's secure ward of Oregon State Hospital, revealing the humanity of psychiatric patients with unflinching tenderness.

Photographs made over three months living among the prostitutes of Bombay's infamous red-light district, documenting lives of extraordinary hardship with intimacy and without judgement.

Portraits of runaway and homeless children in Seattle, centred on the unforgettable Tiny, that became both a landmark photobook and an Academy Award-nominated documentary film.

Born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Studies painting and art history at the University of Pennsylvania.

Receives an MFA in photojournalism from the Annenberg School for Communication at the University of Pennsylvania.

Awarded a Fulbright scholarship to photograph in Turkey. Begins her lifelong practice of deep immersion with her subjects.

Spends thirty-six days living in Ward 81, the women's secure ward of Oregon State Hospital, producing one of the most powerful bodies of work in documentary photography.

Lives for three months among the sex workers of Falkland Road in Bombay, creating images of extraordinary intimacy and courage.

Begins photographing runaway teenagers on the streets of Seattle, centring on a girl called Tiny. The project becomes the book and Oscar-nominated film Streetwise.

Publishes Indian Circus, a luminous and surreal portrait of circus performers and their families across India.

Begins the Twins project, photographing identical twins at the annual Twins Days Festival in Twinsburg, Ohio.

Publishes Tiny: Streetwise Revisited, returning to photograph Tiny thirty years after their first encounter.

Dies in New York City at the age of seventy-five, recognised as one of the most important documentary photographers in American history.

Interested in discussing photography, collaboration, or just want to say hello? I’d love to hear from you.

Contact →