Lee Friedlander was born in 1934 in Aberdeen, Washington, a small lumber town on the Pacific Northwest coast that offered little in the way of artistic stimulation but much in the way of American ordinariness. It was precisely this ordinariness, the clutter and texture of everyday life in the United States, that would become his great and inexhaustible subject. As a teenager he discovered photography and recognised in the camera an instrument perfectly suited to his temperament: curious, patient, alert to the comedy and strangeness hiding in plain sight. By the time he left the Pacific Northwest for Los Angeles and the Art Center School in 1953, he had already begun to develop the observational habits that would sustain one of the longest and most productive careers in the history of American photography.

At the Art Center School, Friedlander received formal training in the technical craft of photography, but it was his own restless looking that truly educated him. He studied the work of Walker Evans and Eugène Atget, absorbing their commitment to the documentary image and their understanding that the vernacular world, shopfronts, street signs, architectural facades, was worthy of sustained artistic attention. After completing his studies, he moved to New York City in 1956 and quickly found work photographing jazz musicians for Atlantic Records. These early assignments brought him into recording studios and nightclubs with John Coltrane, Miles Davis, Charles Mingus, and other giants of the era, producing album cover portraits of remarkable intimacy and spontaneity.

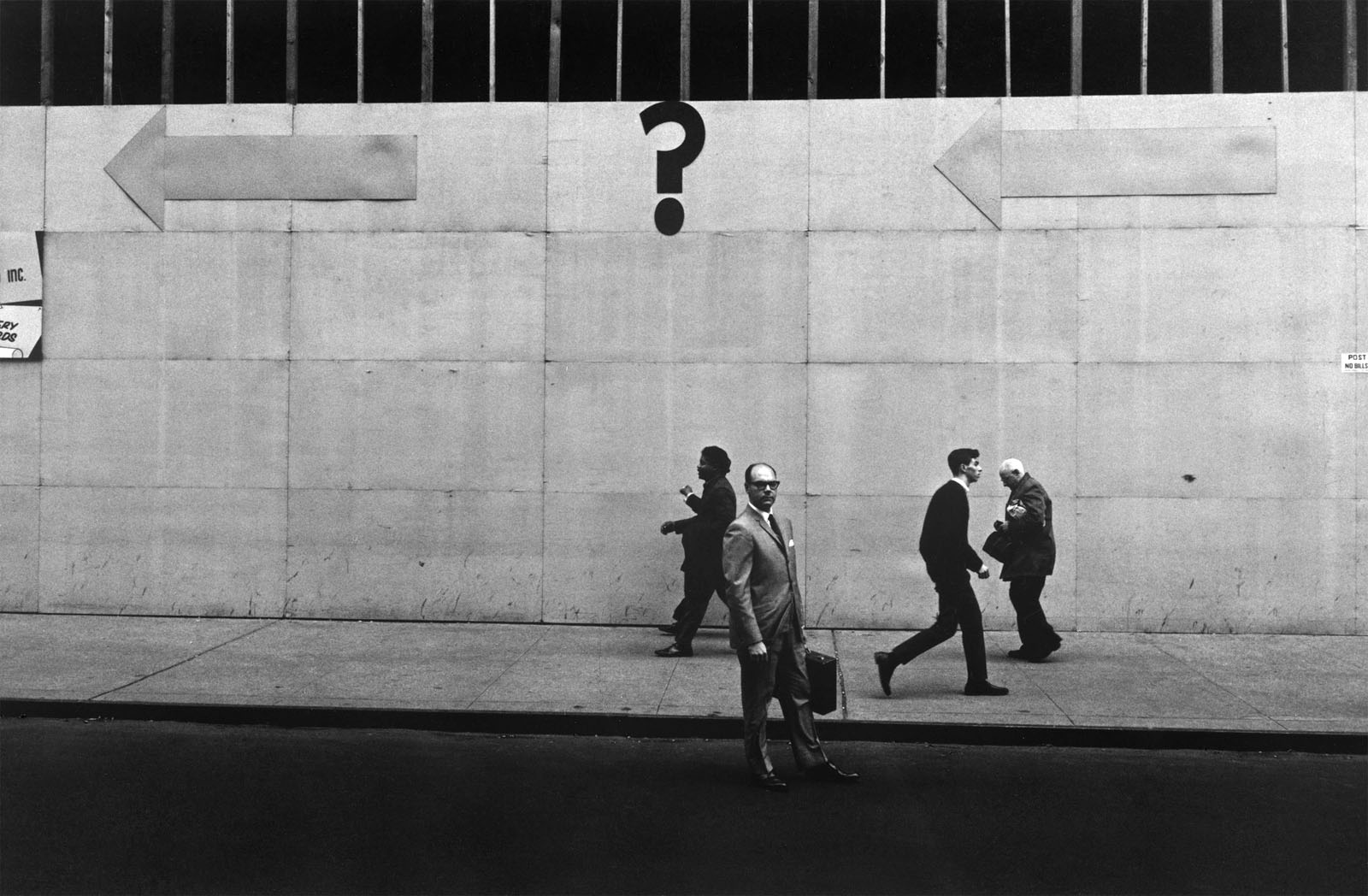

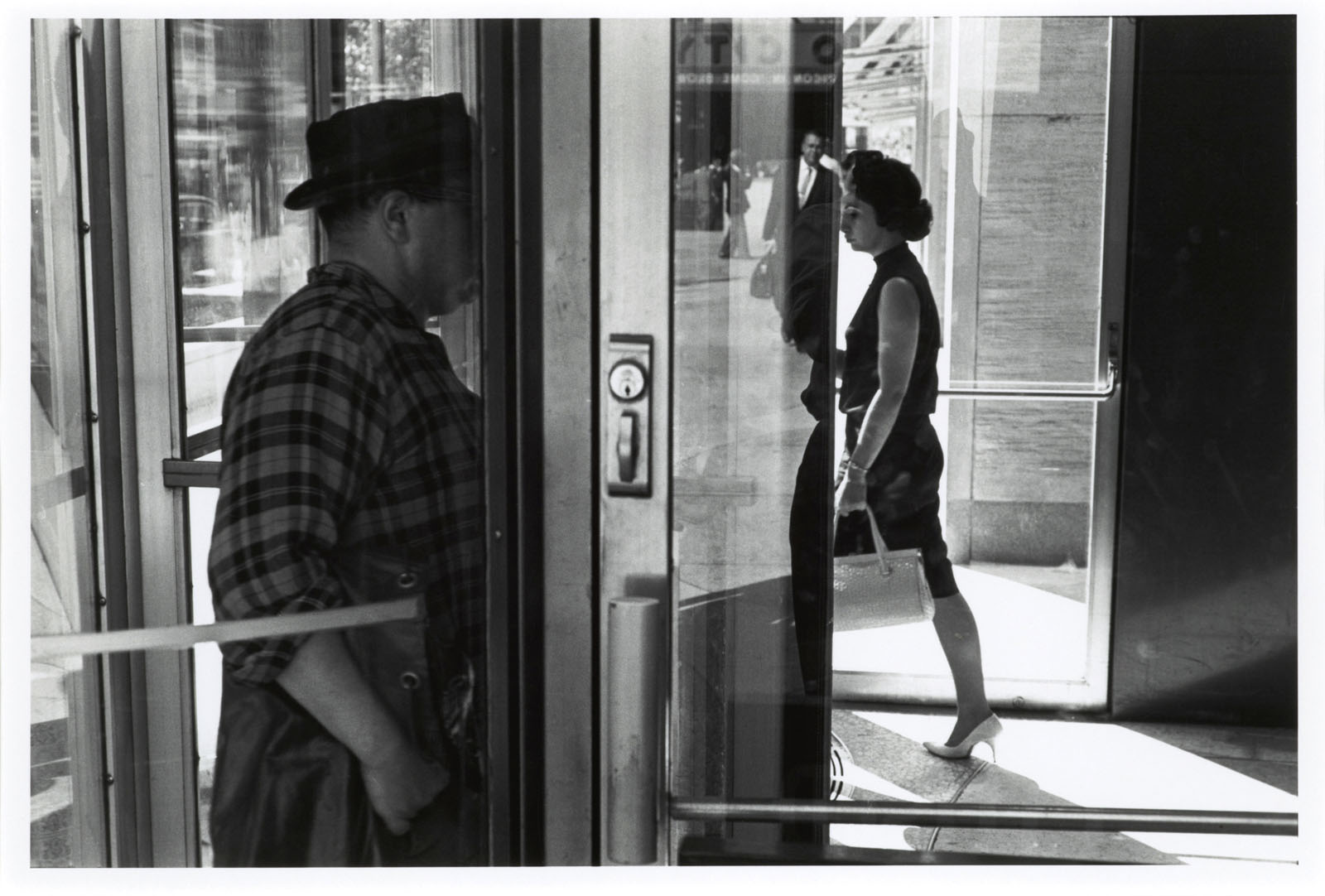

The jazz work was formative, but it was on the streets of New York and on the roads of America that Friedlander discovered his mature vision. By the early 1960s he had begun to develop a photographic language unlike anything that had come before: densely layered compositions in which signs, shop windows, reflections, telephone wires, tree branches, parked cars, and pedestrians competed for attention within a single frame. Where most photographers sought to simplify, Friedlander embraced visual complexity. His pictures were full of information, often to the point of apparent chaos, yet they held together through an underlying compositional intelligence that revealed itself only on sustained inspection. He was deeply influenced by Robert Frank's The Americans, which had demonstrated that personal vision and emotional subjectivity could be as valid as documentary objectivity, but Friedlander took the lesson in a different direction, developing a cooler, more analytical, and more formally inventive approach.

The year 1967 proved pivotal. John Szarkowski, the influential curator of photography at the Museum of Modern Art, selected Friedlander alongside Garry Winogrand and Diane Arbus for the landmark exhibition New Documents. The show argued that a new generation of photographers had turned the documentary tradition inward, using the camera not to reform the world but to explore their own experience of it. For Friedlander, this meant the American social landscape in all its teeming, unglamorous detail: the visual noise of commercial signage, the layered reflections in plate-glass windows, the way a fire hydrant could rhyme with a distant figure, the accidental poetry of the built environment. The exhibition established him as one of the most important photographers of his generation and aligned his work with a broader cultural shift toward irony, complexity, and self-awareness in the visual arts.

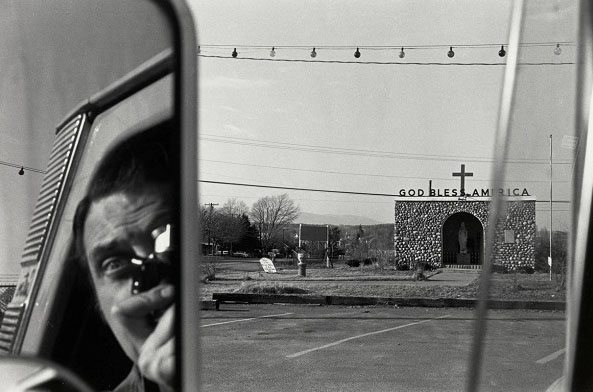

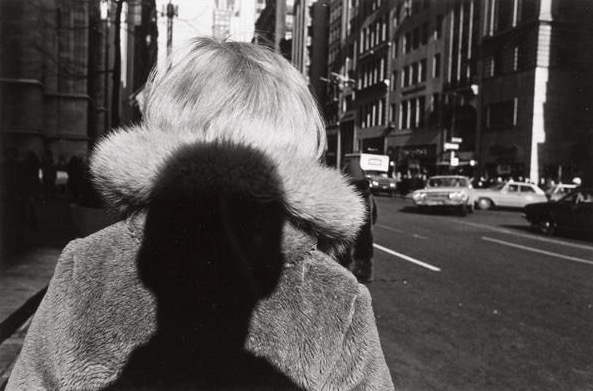

Among Friedlander's most distinctive contributions was his sustained exploration of the photographic self-portrait. Beginning in the mid-1960s, he began systematically inserting his own shadow, reflection, or silhouette into his images. In Self Portrait, published in 1970, he collected these pictures into a book that was playful, conceptually rigorous, and unlike anything that had preceded it. His shadow falls across a bed, stretches along a pavement, or looms over a figure on a park bench. His reflection appears in television screens, car mirrors, and shop windows, layered with the scene beyond. These images raised fundamental questions about the photographer's presence in and relationship to the world he records, anticipating by decades the self-referential concerns that would dominate contemporary art photography.

The decades that followed demonstrated an almost unparalleled productivity and range. Friedlander turned his attention to the American landscape with The American Monument (1976), an exhaustive survey of public statuary, war memorials, and civic monuments that revealed how these objects sit within the indifference and clutter of contemporary life. He photographed factory workers, family gatherings, desert landscapes, and urban parks. He produced Like a One-Eyed Cat (1989), a collection of photographs taken from inside cars that used the windshield and side mirrors as framing devices. He published Nudes (1991), a frank and spatially inventive series that brought his characteristic complexity to the human body. And in Sticks and Stones (2004), he turned to the American built environment, photographing Victorian houses, desert motels, and rural churches with the same layered visual intelligence he had brought to the streets of New York. His relationship to the younger photographers of the New Topographics generation, artists such as Robert Adams, Lewis Baltz, and Stephen Shore, was one of mutual respect and shared interest in the vernacular landscape, though Friedlander's work always retained a more personal and more formally exuberant character than the cool detachment favoured by many of those who followed.

Recognition came steadily and from the highest quarters. In 1963 he received his first Guggenheim Fellowship, followed by a second in 1977. In 1990 he was awarded a MacArthur Fellowship, the so-called genius grant, in recognition of the breadth and significance of his lifetime contribution to photography. In 2005, the Museum of Modern Art mounted a major retrospective that confirmed his position as one of the most important American photographers of the twentieth century. His books, numbering in the dozens, constitute one of the richest and most varied bodies of published photographic work by any single artist.

What is perhaps most remarkable about Lee Friedlander is his endurance. He continued to photograph, publish, and exhibit new work well into his eighties and nineties, maintaining a level of ambition and curiosity that would be extraordinary in an artist of any age. His output showed no sign of diminishing rigour or invention. From the jazz clubs of 1950s New York to the desert monuments of the American West, from his own shadow falling across a city pavement to the tangled branches of a winter tree, Friedlander has spent more than seven decades demonstrating that the world, if you look at it carefully enough, is stranger, funnier, and more visually generous than anyone had previously imagined.