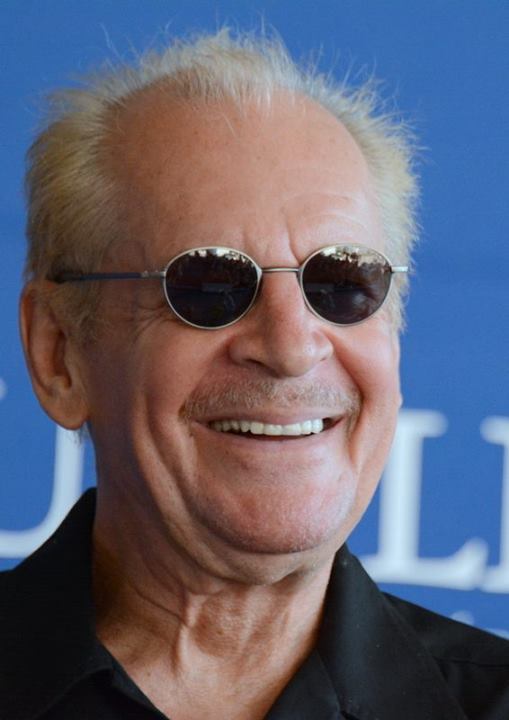

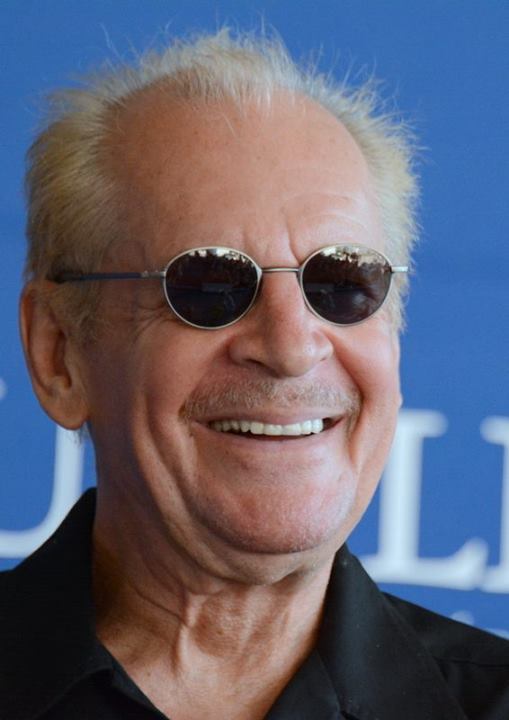

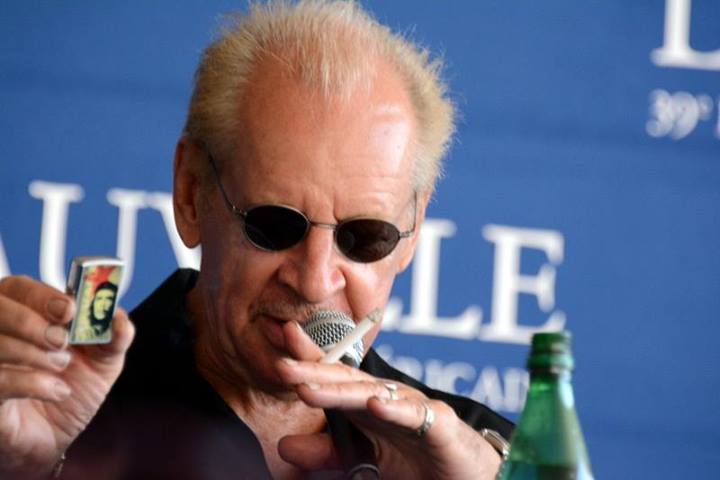

Unflinching chronicler of American youth culture, whose raw, autobiographical photographs of drug use, sexuality, and violence opened a confrontational new chapter in documentary photography.

1943, Tulsa, Oklahoma — Present — American

Larry Clark was born in Tulsa, Oklahoma, in 1943, into a world that would become both the setting and the subject of his most important work. His mother worked as an itinerant baby photographer, travelling from door to door across the state to photograph infants and toddlers for their families. Clark accompanied her from a young age, and the camera became a familiar object in his hands long before he understood its power. That early, almost incidental introduction to the medium planted a seed that would grow into one of the most controversial and consequential bodies of work in the history of American photography.

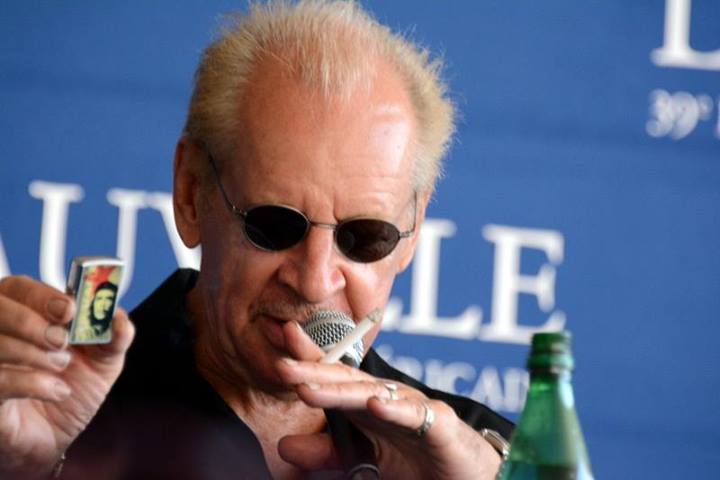

As a young man, Clark studied photography at the Layton School of Art in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, where he received formal training in the technical and compositional foundations of the craft. But the clean, controlled environment of the art school bore little resemblance to the world waiting for him back in Tulsa. When he returned to Oklahoma in the early 1960s, he fell in with a circle of friends who were deep in the grip of amphetamine and heroin addiction. Rather than observe their descent from a safe distance, Clark joined them. He shot up alongside them, slept in their houses, and carried his camera through every moment of their shared existence. The line between photographer and subject dissolved entirely.

The photographs Clark made during this period, spanning roughly from 1963 to 1971, became the raw material for Tulsa, his landmark first book, published in 1971. The images are brutal in their intimacy: young men and women injecting drugs into their arms, loading guns, lying in tangled beds, staring into the camera with expressions that range from euphoria to vacancy to despair. There is no narrative distance in these pictures. Clark was not a journalist parachuting into a crisis; he was a participant documenting his own life and the lives of people he loved. The book's opening line—“i was born in tulsa oklahoma in 1943. when i was sixteen i started shooting amphetamine”—announced a new mode of photographic authorship: confessional, reckless, and unapologetically subjective.

Tulsa sent shockwaves through the photography world. Nothing like it had been published before. The documentary tradition, from the Farm Security Administration to Robert Frank's The Americans, had always maintained at least a notional boundary between the person behind the camera and the world in front of it. Clark obliterated that boundary. His images were not records of someone else's suffering; they were evidence of his own. The book was immediately controversial, praised by some as a courageous act of witness and condemned by others as exploitative or even pornographic. It was banned in several countries and has remained a flashpoint of debate ever since.

Clark's own life in the years following Tulsa was marked by the same chaos that suffused the book. He struggled with addiction for years and spent time in prison. These experiences did not soften his vision; if anything, they deepened it. In 1983, he published Teenage Lust, his second major book, which expanded the autobiographical territory of Tulsa into new and even more provocative terrain. The book mixed photographs from Clark's adolescence with images of teenage runaways and street youth in and around Times Square in New York City. It was simultaneously a memoir and a documentary project, and it cemented Clark's reputation as an artist who refused to look away from the most uncomfortable aspects of American youth culture.

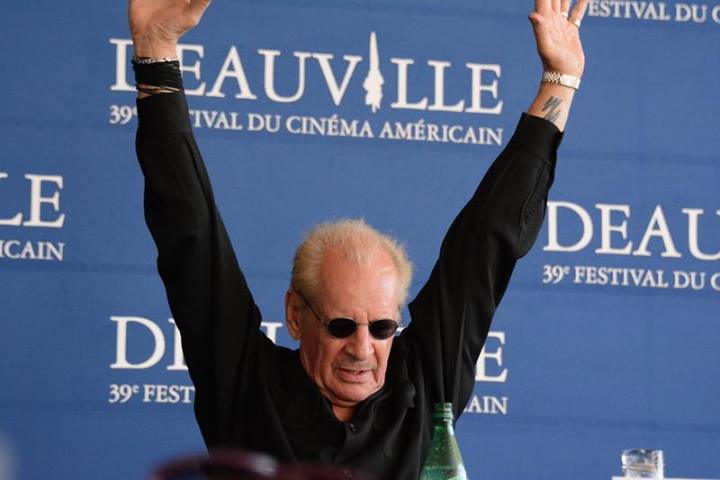

In the 1990s, Clark turned to filmmaking, a transition that would bring his vision to a vastly wider audience. He moved to New York City and immersed himself in the skateboarding and street culture of the Lower East Side. In 1995, he directed Kids, a feature film written by the then-nineteen-year-old Harmony Korine. The film depicted a single day in the lives of sexually active, drug-using teenagers in Manhattan, and it provoked a firestorm of controversy upon its release. Kids was denounced as irresponsible and exploitative, but it was also recognized as a visceral, groundbreaking work of cinema that captured a dimension of adolescent life most filmmakers were afraid to acknowledge. Clark went on to direct several more films, including Bully (2001), Ken Park (2002), and Wassup Rockers (2005), all of which continued to explore the volatile territory where youth, desire, and transgression intersect.

Clark's influence on subsequent generations of photographers and artists has been enormous. Nan Goldin, whose The Ballad of Sexual Dependency brought the diaristic, confessional mode into the mainstream of contemporary art, has acknowledged Clark as a direct predecessor. Ryan McGinley, Dash Snow, and a host of younger photographers working in the tradition of intimate, participatory documentation owe a significant debt to the territory Clark opened up with Tulsa. The entire movement of confessional and autobiographical photography—the idea that the photographer's own life, including its darkest and most private dimensions, is legitimate subject matter—can be traced in large part to Clark's example.

The question of exploitation has followed Clark throughout his career, and it is not easily dismissed. His work forces viewers to confront uncomfortable questions about consent, power, and the ethics of representation, particularly when the subjects are young, vulnerable, or intoxicated. Clark has never offered a tidy resolution to these questions. His defence has always been one of authenticity: he was there, he was part of it, and he owed it to himself and to his subjects to tell the truth of what he saw. Whether that defence is sufficient remains a matter of fierce debate. What is beyond debate is the seismic impact of his work. From Tulsa to Kids and beyond, Larry Clark has consistently refused the comforts of distance, composure, and good taste, producing a body of work that is as disturbing as it is indispensable to the history of photography and film.

I had to tell the truth. I didn't choose this subject, it chose me. Larry Clark

A raw, unflinching photographic document of drug culture among Clark's friends in Oklahoma, widely regarded as one of the most important and controversial photobooks of the twentieth century.

A continuation and expansion of the themes of Tulsa, mixing autobiographical images with photographs of teenage runaways and street youth in New York's Times Square.

Clark's directorial debut, a controversial feature film depicting a day in the life of sexually active, drug-using teenagers in New York City, with a screenplay by the then-nineteen-year-old Harmony Korine.

Born in Tulsa, Oklahoma. His mother works as an itinerant baby photographer, giving him early exposure to the camera.

Studies photography at the Layton School of Art in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Returns to Tulsa and begins photographing his circle of friends.

Begins the body of work that will become Tulsa, photographing the drug use, violence, and daily life of his peers with raw, participatory intimacy.

Publishes Tulsa, one of the most provocative and influential photobooks in the history of the medium. The book's unflinching depictions of drug injection and sexuality cause immediate controversy.

Publishes Teenage Lust, expanding the autobiographical and documentary approach of Tulsa into new territory, including photographs of street youth in Times Square.

Moves to New York City, immersing himself in the skateboarding and street culture of the Lower East Side, which will inform his filmmaking.

Directs Kids, a feature film written by Harmony Korine. The film becomes one of the most debated independent films of the decade.

Directs Bully, a true-crime drama. Continues making controversial films including Ken Park (2002) and Wassup Rockers (2005).

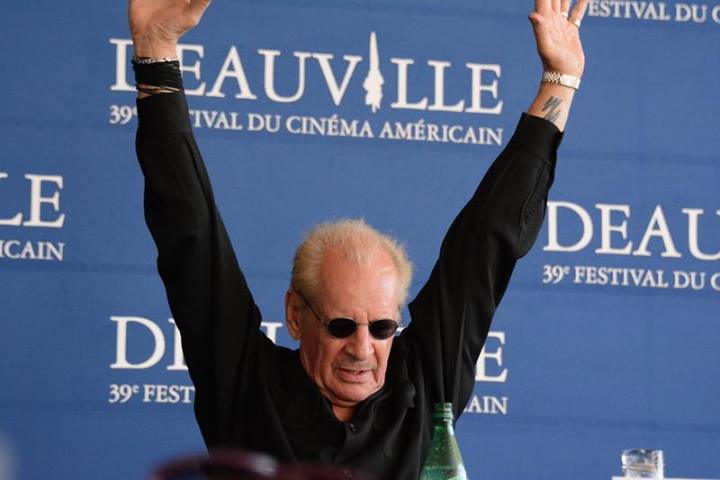

Major retrospective exhibitions in Paris and Los Angeles survey his photographic career, reaffirming his position as one of the most influential and provocative artists of the late twentieth century.

Publishes The Smell of Us, accompanying his film of the same name, continuing to explore youth culture with the same confrontational honesty that defined his earliest work.

Interested in discussing photography, collaboration, or just want to say hello? I’d love to hear from you.

Contact →