Larry Burrows was born Henry Frank Leslie Burrows in 1926 in London, the son of a railway worker who raised his family in the modest terraced streets of the city's north. His childhood coincided with the upheavals of the Depression and the gathering clouds of war, and he left school at sixteen to take a job in the darkroom at Life magazine's London bureau. It was 1942, the height of the Blitz, and the young Burrows found himself immersed in the mechanics of photojournalism at a moment when the stakes of the medium could not have been higher. He learned to process film, make prints, and assist the photographers whose images were shaping the world's understanding of the conflict raging across Europe.

Over the following decade, Burrows rose steadily through the ranks at Life, graduating from darkroom technician to photographer's assistant and eventually to staff photographer. He was mentored by some of the great figures of mid-century photojournalism, and he absorbed their lessons in composition, timing, and the disciplined craft of working under pressure. His early assignments took him across the Middle East and Asia, covering stories ranging from the Suez Crisis to the cultural landscapes of India, but it was his deployment to Southeast Asia in the early 1960s that would define his career and secure his place in the history of photography.

Burrows arrived in Vietnam in 1962, initially on what was expected to be a brief assignment. He would remain, with intermittent returns to London and Hong Kong, for the next nine years. What set Burrows apart from other war correspondents was his commitment to colour photography at a time when most conflict imagery was still being made in black and white. He understood that colour could convey the reality of war with an immediacy and a visceral force that monochrome could not. The red of blood on fatigues, the green density of jungle, the orange of napalm fire — these were not aesthetic choices but moral ones, insisting that the viewer confront the full, unmediated reality of what was happening.

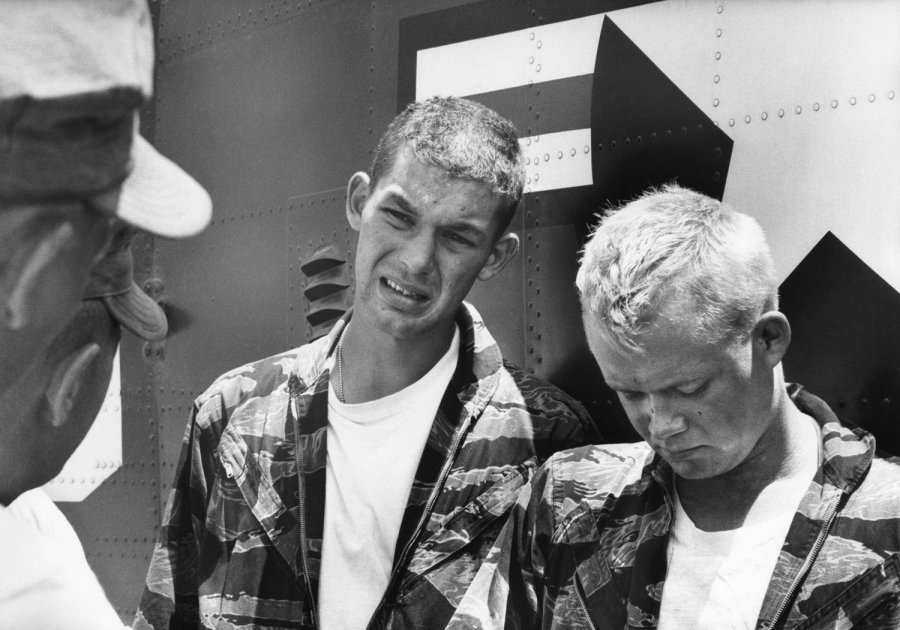

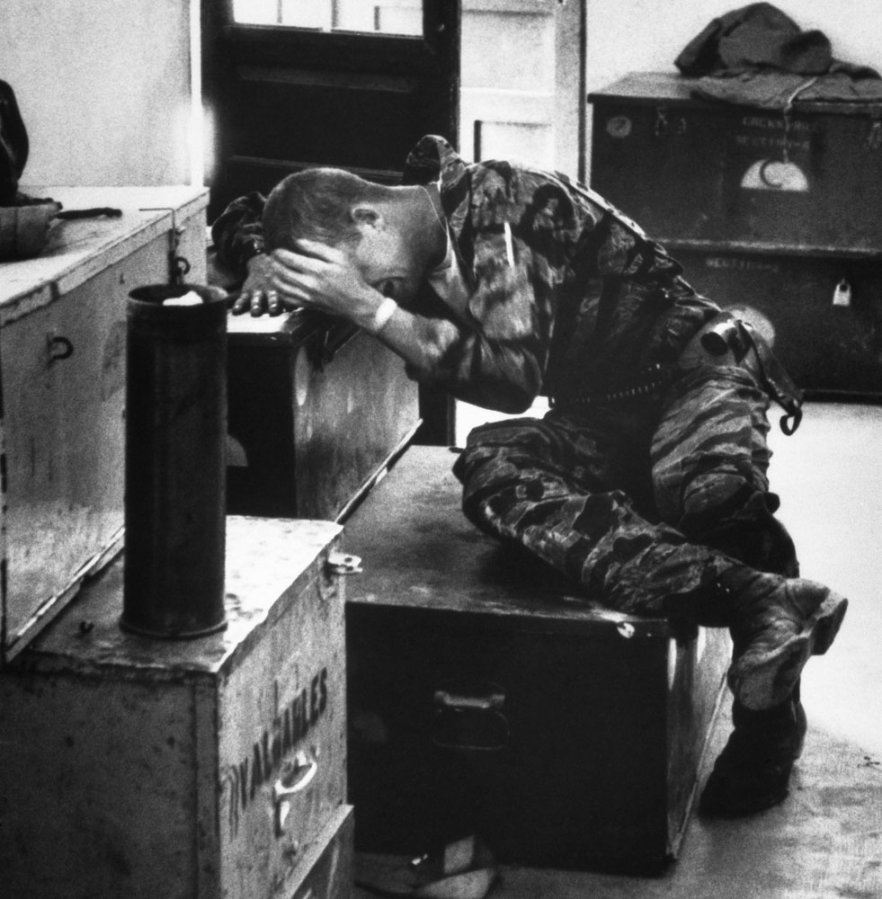

His most celebrated single story, One Ride with Yankee Papa 13, published in Life in April 1965, followed a helicopter crew on a mission that went catastrophically wrong. The sequence of photographs — from the crew's nervous anticipation before the flight, through the chaos of the firefight, to the anguished grief of crew chief James Farley after losing a comrade — was a masterclass in narrative photojournalism. Burrows did not merely witness the event; he constructed a story with the arc and emotional depth of a short novel, each image building upon the last to create an account of war that was both intimate and devastating.

Throughout the mid and late 1960s, Burrows produced a body of work from Vietnam that remains unmatched in its combination of technical brilliance and human empathy. He spent extended periods embedded with combat units, sharing their dangers and earning their trust. His images of wounded Marines at Con Thien, of soldiers wading through mud along the DMZ, of the exhaustion and terror and occasional tenderness of men at war, were published to enormous impact in Life and helped shape American public opinion about the conflict. Yet Burrows never reduced his subjects to symbols or arguments. Each photograph insisted on the individuality of the person before the lens, their particular suffering, their specific courage.

Burrows was acutely aware of the ethical complexities of his position. He photographed both sides of the conflict with the same attentive compassion, and he struggled with the tension between his duty as a journalist and his growing horror at the destruction he was documenting. He was wounded several times and continued to return to the field, driven by what colleagues described as an almost obsessive sense of responsibility to the story and to the people living through it.

On 10 February 1971, Burrows was aboard a Vietnamese military helicopter that was shot down over Laos during Operation Lam Son 719. He was forty-four years old. Also killed in the crash were photographers Henri Huet, Kent Potter, and Keisaburo Shimamoto. Burrows's body was not recovered until 1998, when the crash site was finally located. His death robbed photojournalism of one of its most gifted practitioners, but his legacy endures in every subsequent photographer who has understood that the purpose of war photography is not spectacle but witness — the unflinching, compassionate record of what human beings do to one another and endure.