Josef Sudek was born in 1896 in Kolín, a small town in Bohemia, then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. He trained as a bookbinder before being drafted into the Austro-Hungarian army during the First World War. In 1917, he was wounded on the Italian front and lost his right arm — a devastating injury for anyone, but one that might have seemed particularly cruel for a young man who had already begun to photograph. Yet Sudek refused to allow the loss to define or limit him. He adapted his technique to work one-handed, and the enforced slowness and deliberation that his disability required became, over the decades that followed, an essential quality of his art. He was a photographer for whom patience was not merely a virtue but a method.

After the war, Sudek settled in Prague, the city that would become the great subject and setting of his life's work. He studied at the State School of Graphic Arts and quickly became involved in the photographic culture of the young Czechoslovak Republic. In the 1920s, he was associated with the Czech avant-garde, producing modernist images that reflected the influence of Constructivism and the New Vision movement. But Sudek's temperament was not that of the revolutionary; it was contemplative, introspective, and deeply romantic, and by the 1930s he had moved away from avant-garde experimentation toward a more personal, meditative approach to the medium.

The work that established Sudek's international reputation was his documentation of the restoration of St. Vitus Cathedral in Prague, undertaken between 1924 and 1928. These photographs of the cathedral's interior — its soaring vaults, shafts of light, and intricate stone carvings — revealed Sudek's extraordinary sensitivity to light and atmosphere. He photographed not so much the architecture itself as the quality of light within it, the way that illumination transformed stone into something ethereal and charged with spiritual presence. This preoccupation with light — its textures, its weight, its capacity to transfigure the ordinary — would remain the central theme of his work for the next half-century.

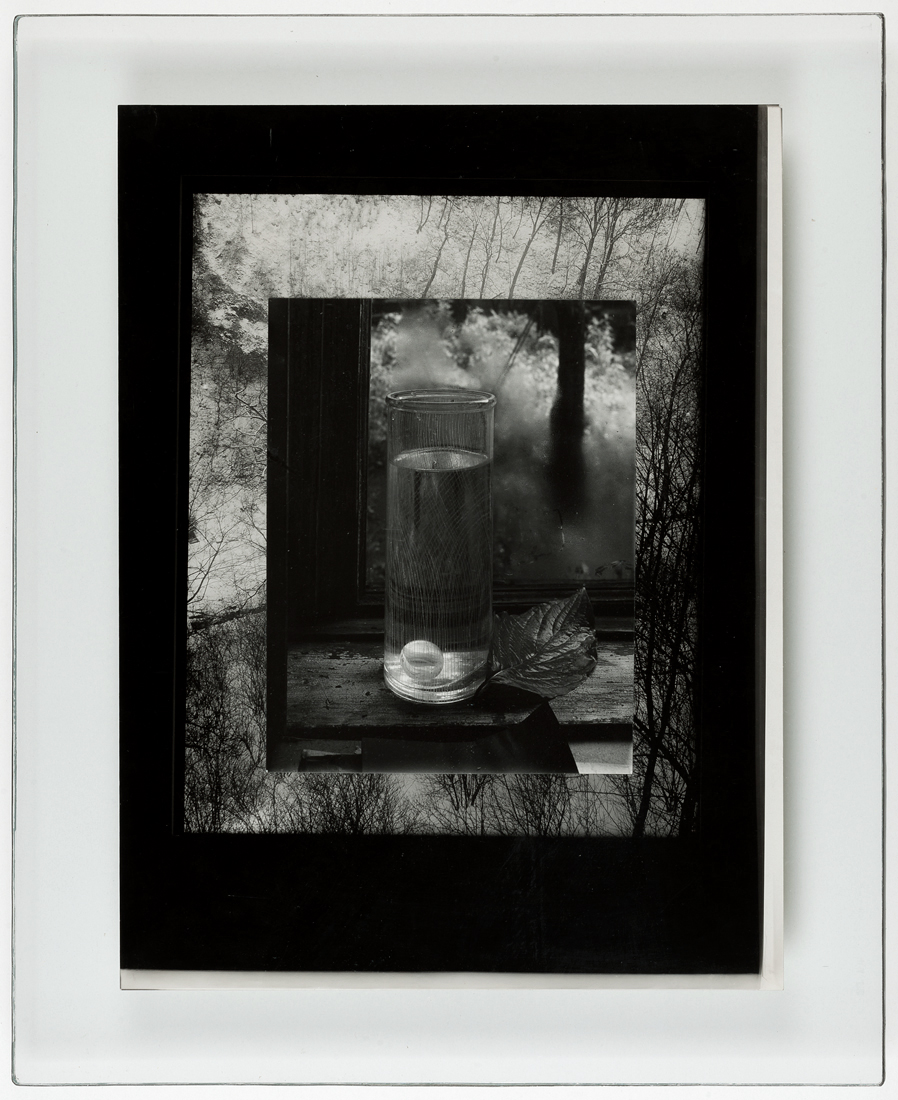

From the 1940s onward, Sudek's practice became increasingly focused on a narrow range of subjects: the view from his studio window, still lifes of glasses, eggs, bread, and flowers arranged on his windowsill, and the streets and gardens of Prague. The window became his most enduring motif. Through it, he observed the changing seasons, the condensation and frost that formed on the glass, the play of light through rain and mist, and the ghostly outlines of the garden beyond. These photographs, made over a period of more than a decade, constitute one of the most sustained meditations on seeing in the history of the medium. They are images about the act of looking itself — about the way that a pane of glass mediates between interior and exterior, between the warmth of the studio and the cold of the world outside.

Sudek's still lifes are equally remarkable. Working with the simplest of objects — a glass of water, a crust of bread, a wilting rose, a crumpled piece of paper — he created compositions of extraordinary luminosity and formal beauty. His mastery of tonal range, achieved through meticulous darkroom work and contact printing, gave his prints a depth and richness that reproductions can only approximate. The light in a Sudek still life seems to emanate from within the objects themselves, as if the glass and bread were not merely reflecting light but generating it. These quiet, intimate images owe something to the tradition of Dutch and Flemish still-life painting, but their emotional register is uniquely Sudek's own — tinged with a melancholy that speaks of solitude, transience, and the passage of time.

In the 1950s and 1960s, Sudek embarked on a series of panoramic photographs of Prague, using a large panoramic camera that produced elongated images of the city's rooftops, bridges, and gardens. These panoramas, with their sweeping vistas and atmospheric effects, captured the city in all its moods — wreathed in fog, blanketed in snow, luminous in summer light. They constitute a love letter to Prague, a comprehensive portrait of a city that Sudek knew more intimately than any other photographer. Alongside the panoramas, he also produced a series of abstract studies using glass objects, creating images he called Labyrinths — shimmering, mysterious compositions in which light is refracted, reflected, and dispersed into patterns of pure visual poetry.

Sudek lived simply, almost monastically, in his small studio in the Malá Strana district of Prague. He was a solitary figure, devoted to music — he hosted regular concerts in his studio — and to his work. He photographed daily, printed meticulously, and accumulated a vast archive of negatives that documented not just Prague but his own inner life. He worked through the Nazi occupation, through the Communist takeover, through decades of political upheaval, maintaining his practice with a quiet stubbornness that was itself a form of resistance.

Josef Sudek died in Prague in 1976, at the age of eighty. He is recognised as one of the greatest photographers of the twentieth century and the most important Czech photographer in the history of the medium. His work demonstrates that photography need not reach for the exotic or the dramatic to achieve profundity — that a view from a window, a glass on a sill, a misty morning in a familiar city can, when seen with sufficient patience and love, become the subject of art as deep and enduring as any in the medium's history.