The godfather of conceptual art who dismantled the boundaries between text, image, painting, and photography, using wit, appropriation, and radical irreverence to challenge every assumption about what art could be.

1931, National City, California – 2020, Los Angeles, California — American

John Baldessari was born in 1931 in National City, California, a working-class town near the Mexican border just south of San Diego. His father was a salvage dealer who had emigrated from Austria, and his mother was Danish. It was not a background that naturally led to the art world, and Baldessari's path to becoming one of the most influential artists of the twentieth century was characteristically circuitous. He studied at San Diego State College, earning his bachelor's and master's degrees, and spent more than a decade teaching art in public schools and community colleges while developing a painting practice that, by the mid-1960s, had reached a crisis of faith in the conventions of traditional picture-making.

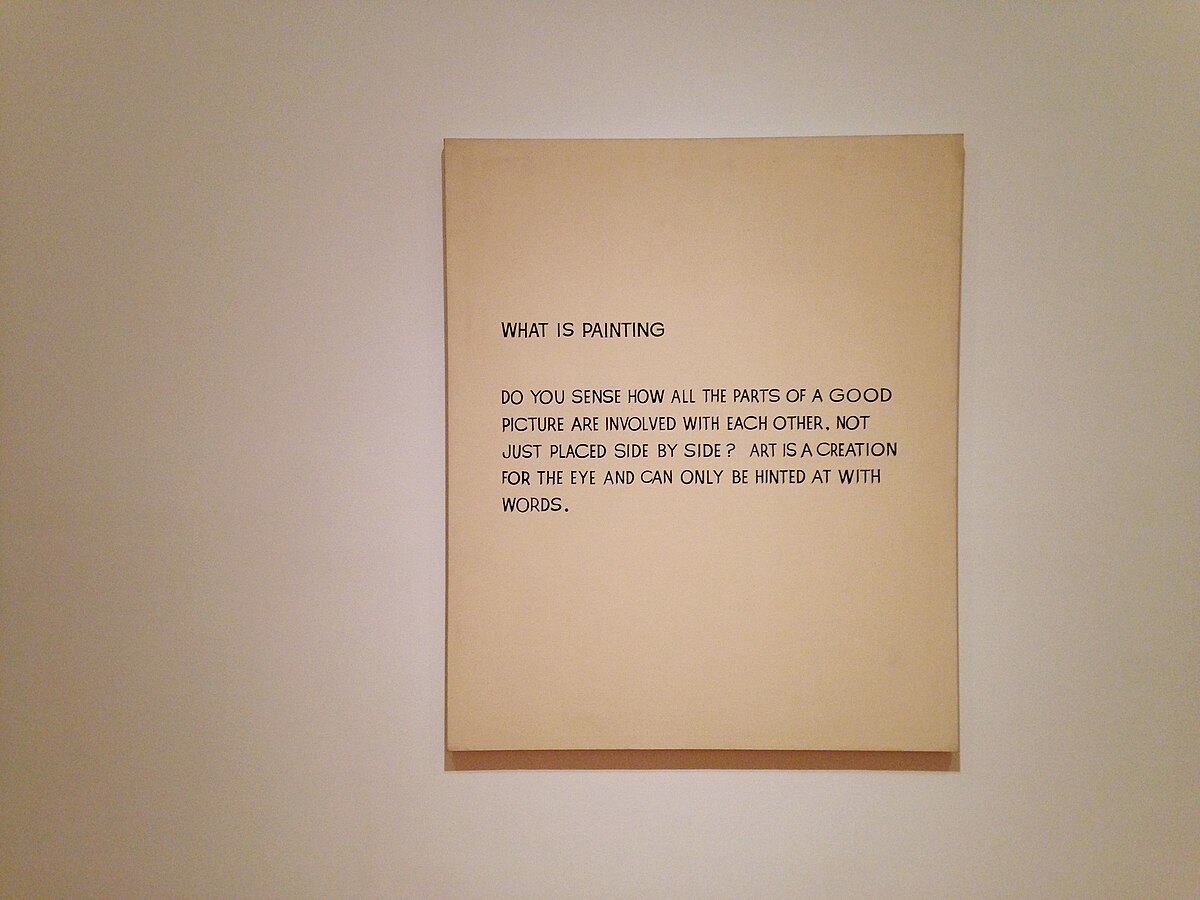

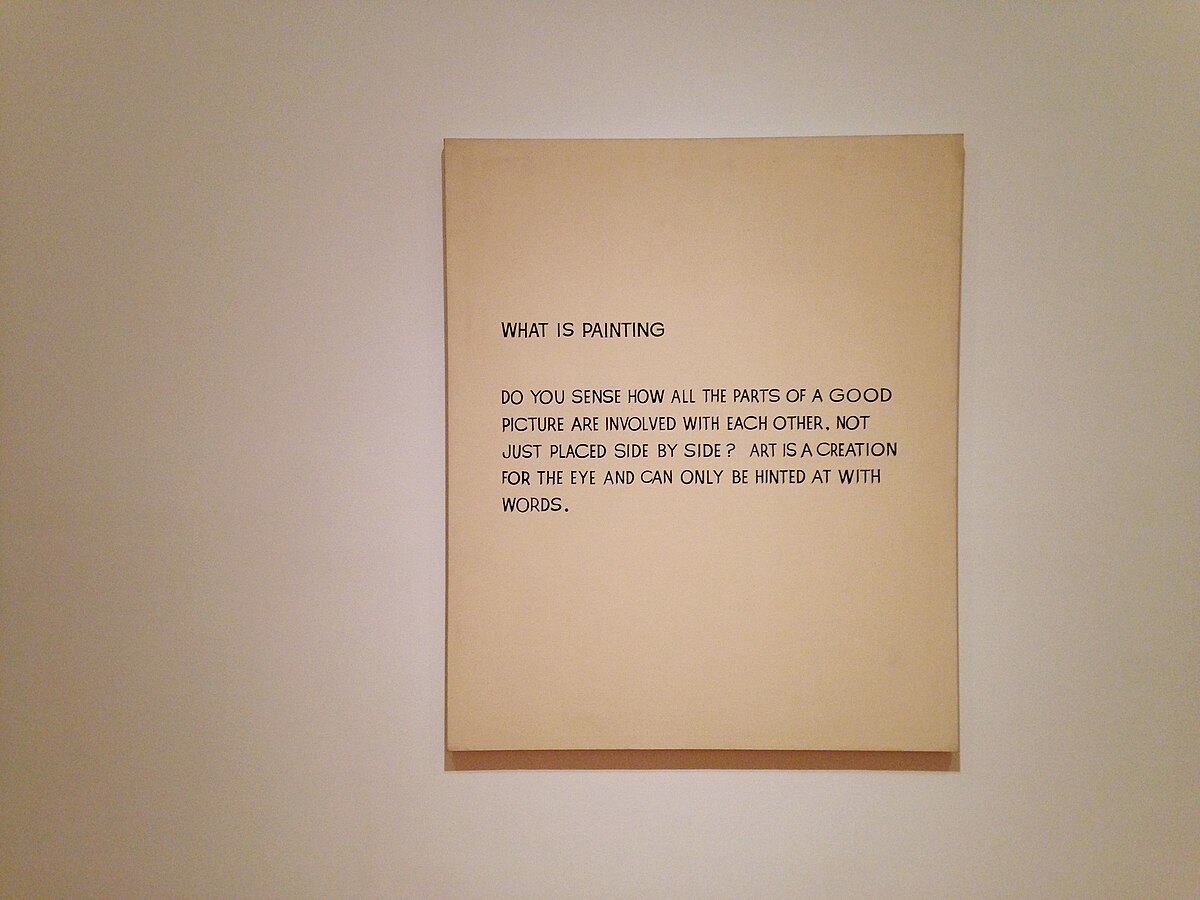

The breakthrough came when Baldessari began to introduce text into his canvases. Rather than painting images, he hired a sign painter to letter sentences onto canvas — statements about art, fragments of art criticism, banal observations, and deadpan instructions. Works such as What Is Painting (1966–68) and Wrong (1966–68) replaced the expressive gesture of the painter with the flat, impersonal authority of the sign. These text paintings were simultaneously a critique of abstract expressionism's cult of authenticity, a homage to the readymade tradition of Marcel Duchamp, and a demonstration that the idea behind a work of art could be more interesting than its physical execution.

In 1970, Baldessari performed what remains one of the most dramatic gestures in the history of contemporary art. He gathered all of the paintings he had made between 1953 and 1966, transported them to a crematorium in San Diego, and burned them. The resulting ashes were baked into cookies and placed in an urn, and the entire event was documented as The Cremation Project. It was an act of liberation — a public declaration that the artist was finished with painting as it had been understood and was free to pursue whatever form his ideas demanded. From that point forward, Baldessari worked primarily with photography, video, film stills, text, and the vast reservoir of found images that the media-saturated culture provided in abundance.

Central to Baldessari's practice was the photographic image, though he used it in ways that no conventional photographer would recognise. He appropriated photographs from films, advertisements, newspapers, and his own staged scenarios, then cropped, juxtaposed, overlaid with coloured dots, combined with text, and rearranged them into compositions that interrogated the mechanics of visual meaning. His signature coloured dots — bright circles placed over the faces of figures in found photographs — simultaneously concealed and revealed, drawing attention to the conventions of portraiture while creating playful, almost cartoonish compositions that belied their conceptual sophistication.

In 1970, Baldessari joined the faculty of the California Institute of the Arts (CalArts), where he would teach for nearly three decades. His influence as a teacher was immense and arguably as significant as his own artistic production. Among his students were David Salle, Jack Goldstein, Matt Mullican, Tony Oursler, James Welling, and Barbara Bloom — artists who would go on to define the Pictures Generation and shape the course of American art in the 1980s and beyond. Baldessari taught by example and by provocation, encouraging students to question every assumption, to find art in the most unlikely places, and above all to reject the boring.

Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, Baldessari produced an extraordinary volume of work that drew on cinema, advertising, and popular culture. His large-scale photomontages assembled fragments of film stills into compositions that suggested narratives without resolving them, inviting viewers to construct their own stories from the juxtaposed images. These works anticipated the image-saturated culture of the internet age by decades, exploring how meaning is produced through the collision and recombination of visual fragments. His wit was always evident — Baldessari possessed a gift for visual humour that was rare in the often solemn world of conceptual art — but beneath the jokes lay a rigorous investigation into the nature of representation, meaning, and the relationship between words and pictures.

In 2009, Baldessari was given a major retrospective at the Tate Modern in London, and in 2014 he was awarded the National Medal of Arts by President Obama. He continued to work prolifically until late in life, his output encompassing prints, sculpture, installation, video, and public commissions alongside his photographic works. When he died in 2020 at the age of eighty-eight, he left behind a body of work that had fundamentally expanded the possibilities of what art — and what photography within art — could be.

Baldessari's legacy is inseparable from his insistence that art should engage the mind as much as the eye. He demonstrated that the photographic image, freed from the conventions of fine art photography, could become a tool for philosophical inquiry, cultural critique, and sheer visual pleasure. His influence extends far beyond the art world, reaching into graphic design, advertising, and the visual culture of everyday life. He remains the great liberator — the artist who showed that the boundaries between high and low, text and image, serious and funny, were not walls but invitations to play.

Art comes from art. I learned everything about photography from painting. And I learned everything about painting from photography. John Baldessari

The ritualistic burning of all paintings made between 1953 and 1966, an act of artistic liberation that freed Baldessari from conventional painting and launched his conceptual practice with photography and text.

A series of photographs attempting the impossible task described in the title, exploring chance, intention, and the gap between concept and execution that lies at the heart of art-making.

Large-scale photomontages combining cropped fragments of faces from found photographs, creating vivid, disorienting compositions that interrogate the conventions of portraiture and identity.

Born in National City, California, near the Mexican border south of San Diego.

Earns MA from San Diego State College. Begins teaching art in public schools while developing his painting practice.

Begins the text paintings, hiring a sign painter to letter sentences onto canvas, marking his departure from conventional picture-making.

Performs The Cremation Project, burning all paintings from 1953–1966. Joins the faculty at California Institute of the Arts.

Produces Throwing Three Balls in the Air to Get a Straight Line, one of his most celebrated photographic works.

Begins large-scale photomontage works combining film stills with coloured dots, establishing his signature visual language.

Major retrospective Pure Beauty at Tate Modern, London, touring internationally to major museums.

Awarded the National Medal of Arts by President Obama in recognition of his contribution to American culture.

Dies in Los Angeles at the age of eighty-eight. His influence on conceptual art, photography, and art education endures as one of the most far-reaching of any American artist of his era.

Interested in discussing photography, collaboration, or just want to say hello? I’d love to hear from you.

Contact →