Irving Penn was born in Plainfield, New Jersey, in 1917, the elder of two sons in a family of modest means. His younger brother, Arthur Penn, would go on to become one of Hollywood's most celebrated directors, but it was Irving who first found his way into the visual arts. As a teenager he discovered a passion for drawing and design, and in 1934 he enrolled at the Philadelphia Museum School of Industrial Art (now the University of the Arts), where he studied under the legendary Alexey Brodovitch — the art director of Harper's Bazaar whose teaching methods and visual philosophy shaped an entire generation of American photographers and designers. Under Brodovitch's exacting tutelage, Penn absorbed the principles of clean composition, bold graphic design, and the conviction that every element within a frame must earn its place.

After graduating in 1938, Penn worked briefly as a graphic designer and then secured a position as art director at Saks Fifth Avenue, where he oversaw the department store's advertising art. The job sharpened his eye for the relationship between image and commerce, but Penn grew restless. In 1941, he left New York to spend a year painting in Mexico and the American South, testing whether he might become a fine artist. He returned to New York in 1943 convinced that painting was not his calling, and at the invitation of Alexander Liberman, the art director of Vogue, he joined the magazine as a cover photographer. It was the beginning of one of the most productive and enduring partnerships in the history of publishing.

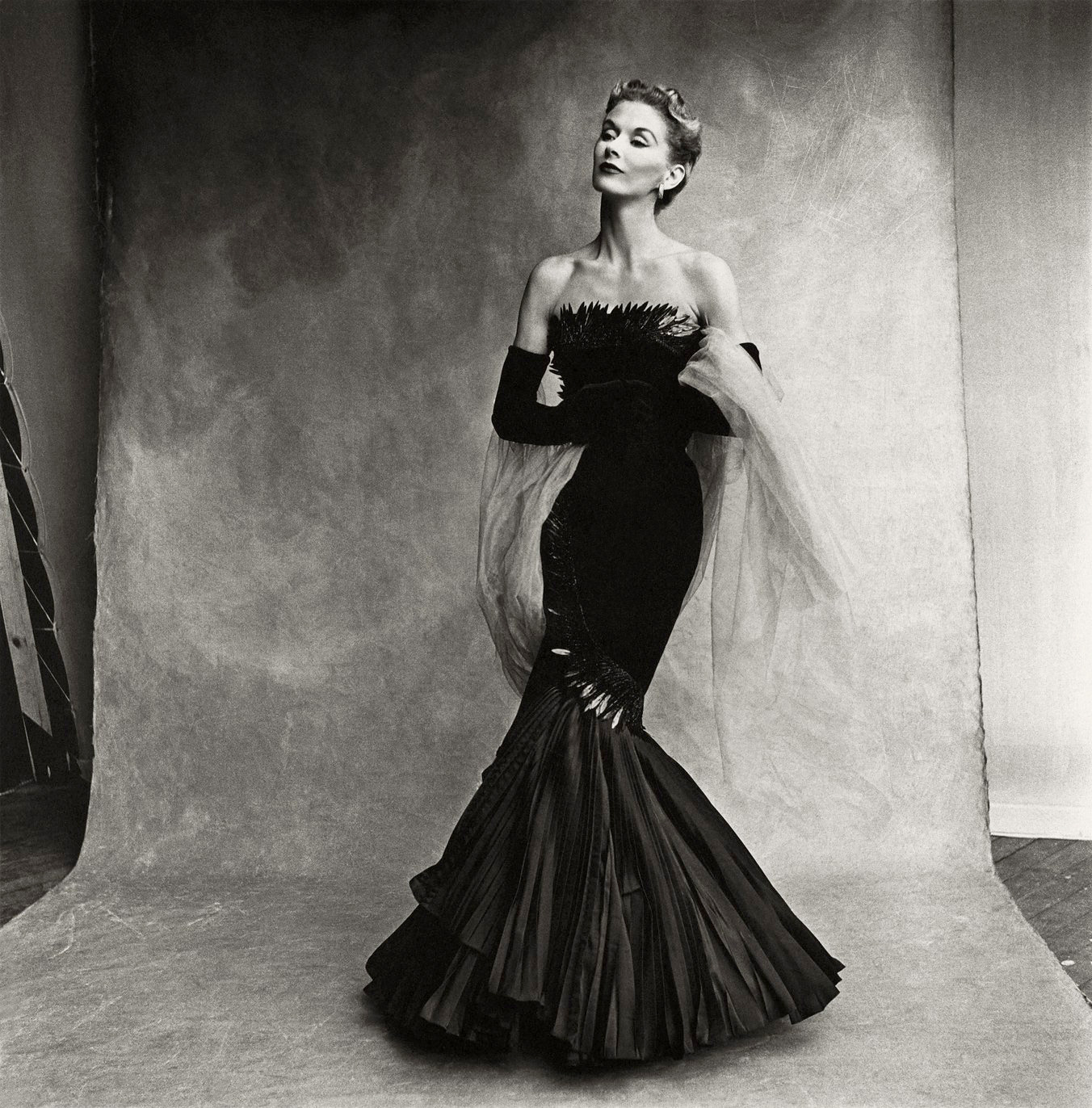

From the outset, Penn's approach to the photographic image was defined by an almost ascetic minimalism. Where other fashion photographers of the era favoured elaborate sets and theatrical lighting, Penn stripped his compositions to their essentials. He placed his models and sitters against simple grey or white backdrops, using natural or carefully controlled light to achieve a purity of tone that was at once stark and luminous. The backgrounds were not merely neutral — they were active elements in the composition, expanses of empty space that drew the eye to the precise contour of a sleeve, the angle of a jaw, the geometry of a hat brim. Penn understood that in photography, as in architecture, emptiness is a form of eloquence.

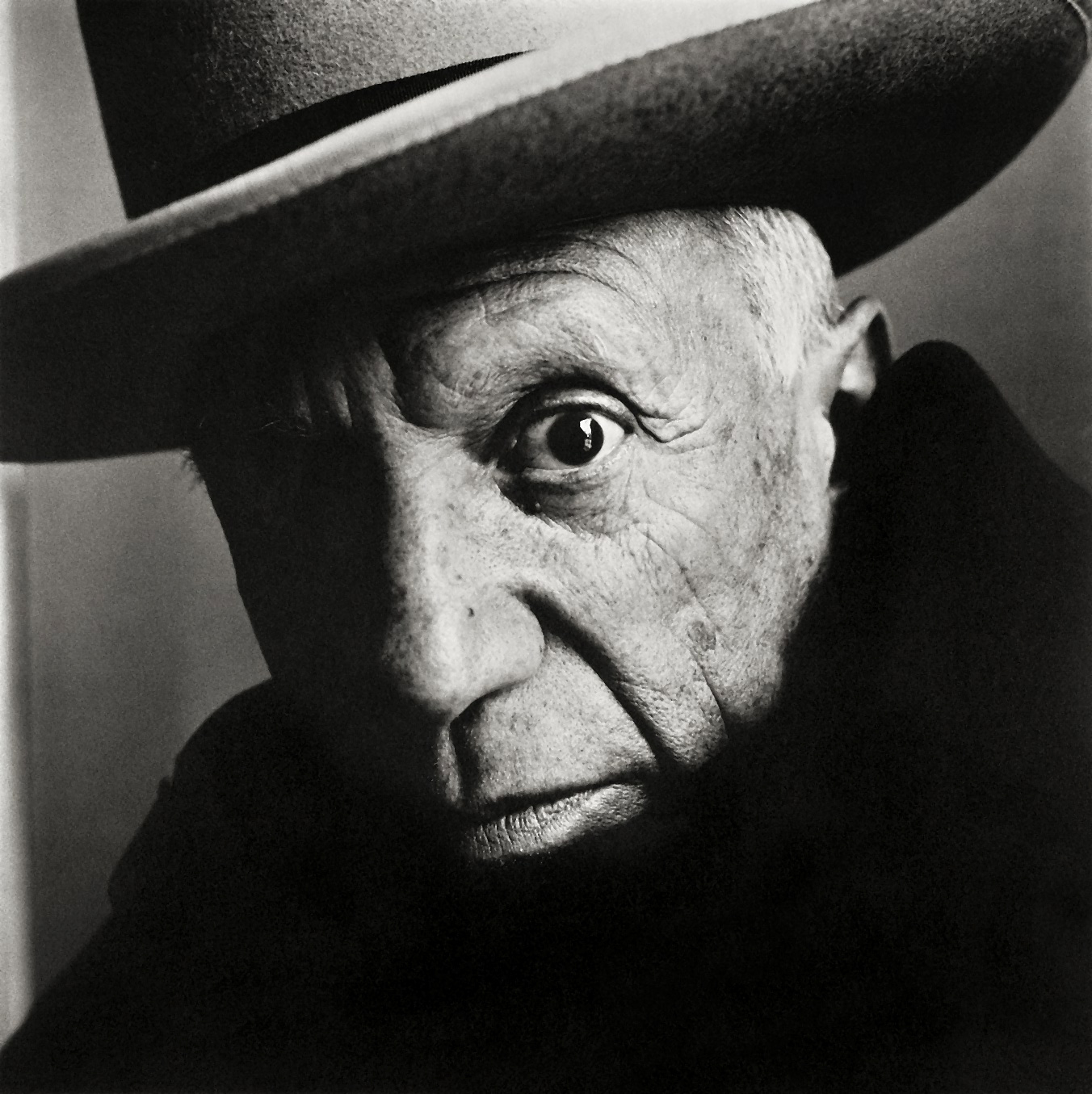

Among his most celebrated innovations were the Corner Portraits, a series begun in 1948 in which Penn placed his subjects — among them Igor Stravinsky, Marcel Duchamp, Spencer Tracy, and Marlene Dietrich — into a narrow V-shaped angle formed by two converging studio walls. The effect was both claustrophobic and revelatory. Deprived of their customary ease and social armour, Penn's sitters were compelled to inhabit a compressed, almost confrontational space, and in doing so they revealed aspects of character that a more conventional portrait setting might never have disclosed. The corner became a psychological instrument, a device for stripping away performance and exposing the person beneath.

Penn's vision extended far beyond fashion and portraiture. Throughout his career he produced a remarkable body of still-life work that demonstrated his ability to find beauty and formal interest in the most unlikely subjects. His Frozen Foods series of 1977 transformed packets of peas, fish fingers, and ice-cream bars into objects of sculptural grandeur. His Cigarettes series of 1972 presented discarded cigarette butts — crumpled, stained, lipstick-marked — as monumental forms, printed at enormous scale in rich platinum-palladium tones. And his studies of skulls, decaying flowers, and street debris revealed a sensibility that could perceive elegance and gravity in the cast-off remnants of daily life. In Penn's hands, a discarded glove or a wilting bloom became an object worthy of the same attention that Chardin or Morandi had lavished on their own humble still lifes.

In 1950, Penn married the Swedish-born model Lisa Fonssagrives, widely regarded as the first supermodel and one of the most photographed women of the twentieth century. She became his most frequent subject and his greatest muse, appearing in some of his finest fashion photographs — among them the iconic Woman in Chicken Hat (1949) and Harlequin Dress (1950). Their partnership was both professional and deeply personal, a creative symbiosis in which Fonssagrives's extraordinary poise and physical intelligence met Penn's uncompromising formal vision.

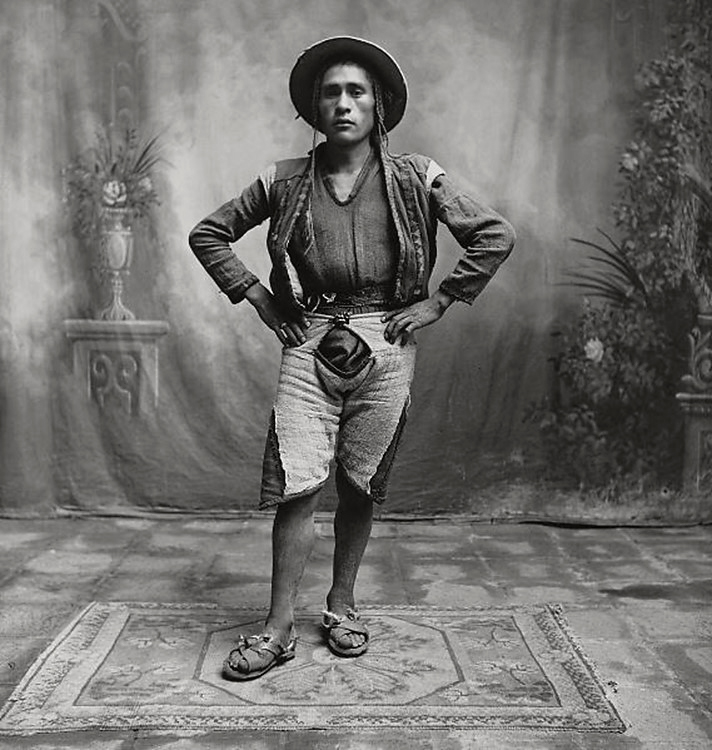

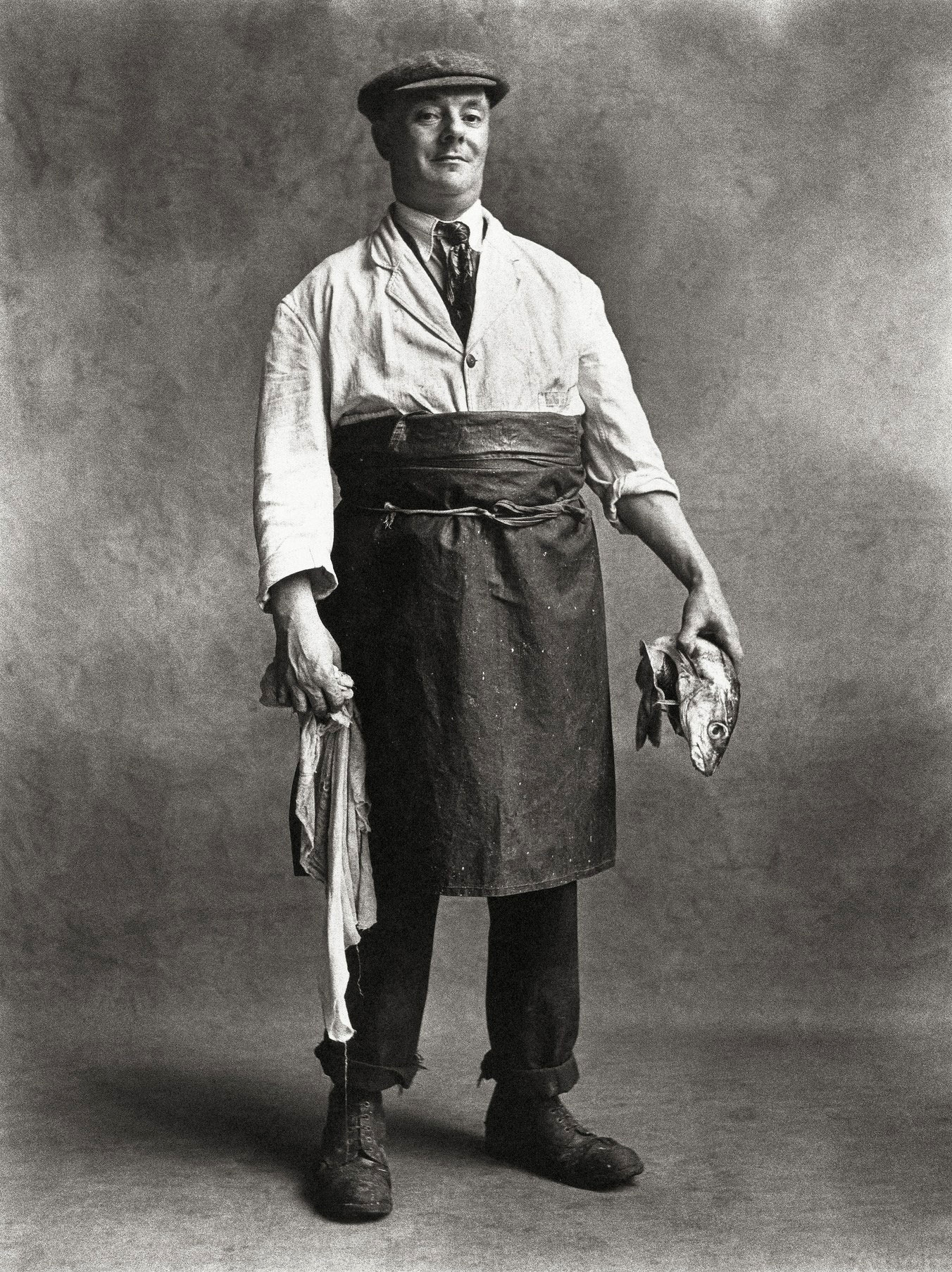

Beginning in the 1960s, Penn embarked on an ambitious series of ethnographic portraits, travelling to Dahomey, Nepal, Cameroon, New Guinea, Peru, and Morocco to photograph indigenous peoples and traditional tradespeople. Working with a portable studio that he transported to remote locations, Penn applied the same rigorous aesthetic he used for his Vogue fashion work — the neutral backdrop, the controlled light, the unflinching attention to form — to subjects who had never before been photographed in this way. The resulting images, published as Worlds in a Small Room in 1974, and the earlier Small Trades series of Parisian and London tradespeople (1950–51), demonstrated that Penn's formal language was universal: it could dignify a Peruvian shepherd or a Parisian chimney sweep with the same sculptural authority it brought to a Balenciaga gown.

In 1984, Penn began making platinum-palladium prints of his photographs, a laborious and technically demanding process that yielded images of extraordinary tonal range and archival permanence. The warm, velvety surface of the platinum print — with its subtle gradations from the deepest black to the most delicate silver-grey — became the ideal vehicle for Penn's vision, lending his images a physical presence and a sense of handmade craft that elevated them to the status of fine-art objects. Penn's career with Vogue and Condé Nast spanned more than sixty years, making it one of the longest and most productive partnerships in the history of magazine publishing. He died in New York City in 2009, at the age of ninety-two, leaving behind a body of work that stands as one of the most formally perfect and wide-ranging achievements in the history of photography.