Hippolyte Bayard was born on 20 January 1801 in Breteuil-sur-Noye, a small town in the Oise department of northern France. He moved to Paris as a young man and found steady employment as a clerk in the Ministry of Finance, a position he would hold for much of his life. But behind the unremarkable façade of a government functionary lay an inventive mind absorbed by the scientific ferment of the age. By the late 1830s, as rumours circulated through Parisian intellectual circles that several experimenters were on the verge of fixing images produced by light, Bayard had already been conducting his own photographic experiments in quiet isolation, working evenings and weekends with chemicals and paper in his modest quarters.

By early 1839, Bayard had developed a direct positive process on paper — a method that produced a unique positive image without the intermediate step of a negative. His process involved exposing light-sensitised paper in a camera obscura, then darkening the paper with potassium iodide and fixing the result with a salt solution. The images were delicate, beautiful, and unlike anything produced by either Daguerre's silvered copper plates or Fox Talbot's calotype negatives. On 24 June 1839, Bayard mounted the first public exhibition of photographs in history, displaying thirty of his direct positive prints at a charity auction in Paris — weeks before the French government formally acquired and announced Daguerre's process.

Yet history dealt Bayard an unkind hand. François Arago, the influential physicist and politician who championed Daguerre's invention before the French Academy of Sciences, persuaded Bayard to delay his own public announcement. Whether Arago acted from genuine conviction that Daguerre's process was superior, or from political calculation, the result was devastating: when the daguerreotype was presented to the world on 19 August 1839 with great fanfare and government sponsorship, Bayard's earlier achievement was largely ignored. The French government purchased Daguerre's patent and gave it freely to the world. Bayard received only a small grant to purchase better equipment.

It was in response to this perceived injustice that Bayard created what is now regarded as the first intentionally staged photograph: Self Portrait as a Drowned Man, made in October 1840. The image shows Bayard posed as a half-naked corpse, eyes closed, hands folded, as though he had drowned himself in despair. On the reverse, he wrote a bitter text in the voice of the deceased, declaring that the government which had been so generous to Daguerre had done nothing for him, and that his body had been at the morgue for three days without anyone recognising or claiming it. The photograph was at once a political protest, a mordant joke, and an astonishing act of artistic self-awareness — the medium's first staged fiction, created when photography itself was barely months old.

Despite his disappointment, Bayard continued to photograph prolifically throughout the 1840s and 1850s. He turned his camera on the streets and rooftops of Paris, producing views of Montmartre, the Seine, and the rapidly transforming cityscape with a compositional sensitivity that anticipated the architectural photography of later decades. He was a founding member of the Société héliographique in 1851 and of the Société française de photographie in 1854, contributing actively to the institutional life of the new medium even as his own pioneering role went unacknowledged.

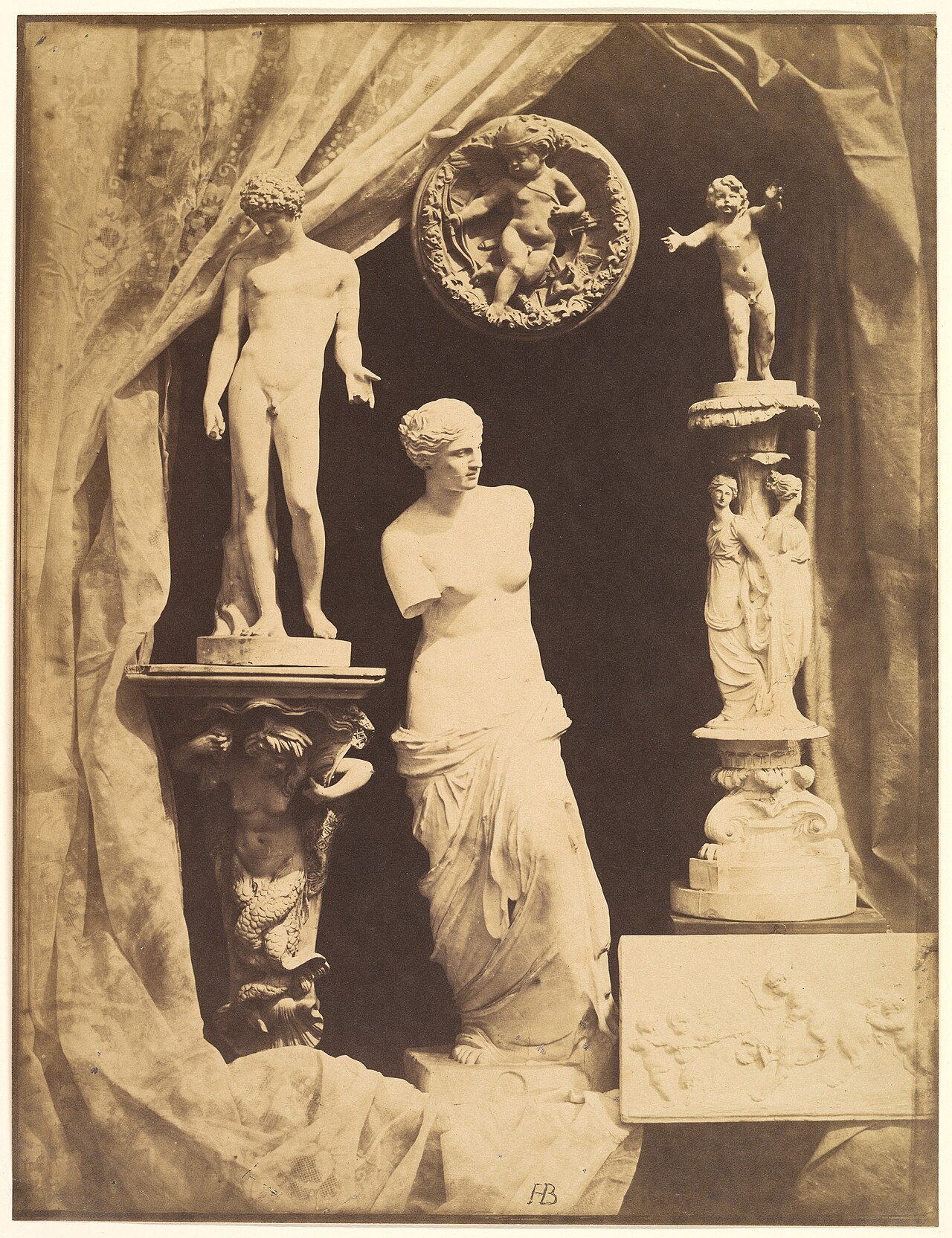

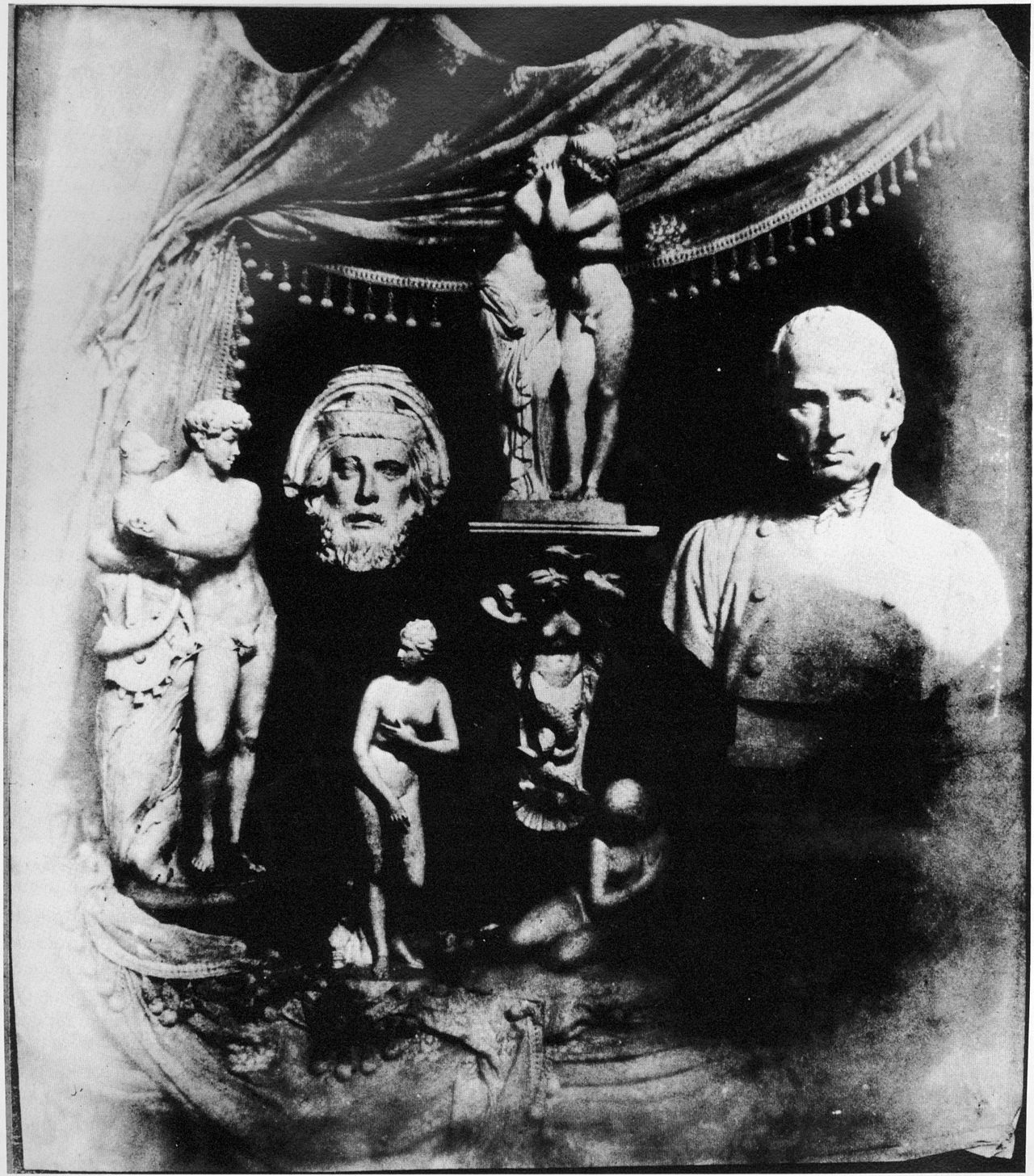

Bayard also documented the aftermath of the Revolution of 1848 and the construction of the barricades in Paris, producing some of the earliest photographic records of urban political upheaval. His later work included portraits, architectural studies, and still lifes, all characterised by a quiet dignity of composition and a subtle tonal range that reflected the distinctive qualities of his direct positive process. He eventually adopted both the daguerreotype and the calotype, demonstrating a pragmatic adaptability alongside his inventive spirit.

He retired from the Ministry of Finance and spent his final years in Nemours, south of Paris, where he died on 14 May 1887 at the age of eighty-six. For much of the twentieth century, Bayard remained a footnote in photographic history, overshadowed by Daguerre and Talbot. It was only through the work of later scholars that his contributions were fully reassessed and his direct positive prints recognised for their beauty and historical significance. Today, Bayard is understood not only as one of the true co-inventors of photography but as the medium's first conceptual artist — a figure who grasped, before anyone else, that the camera could be used not merely to record reality but to construct fictions, tell stories, and make arguments.

The poignant irony of Bayard's career is that the very quality that makes his Drowned Man so remarkable — its self-conscious manipulation of photographic truth — was precisely the aspect of the medium that the nineteenth century was least prepared to appreciate. In an age that valued photography for its mechanical objectivity, Bayard was already exploring its capacity for subjectivity, performance, and protest. His work anticipates the staged photography of Cindy Sherman, the conceptual self-portraiture of modern art, and the ongoing debates about truth and fiction that remain central to photographic practice today.