The provocateur of fashion photography, whose confrontational images of powerful, sexually charged women in opulent and threatening settings redrew the boundaries between commercial photography, fine art, and transgression.

1920, Berlin, Germany – 2004, Los Angeles, California — German-Australian

Helmut Newton was born Helmut Neustädter on October 31, 1920, in Berlin, Germany, into a prosperous Jewish family. His father owned a button factory, and the young Helmut grew up in the comfortable bourgeois world of Weimar-era Berlin — a city of cabarets, cinema, and avant-garde art that would leave an indelible mark on his visual imagination. He discovered photography as a teenager, and by the age of sixteen had made the decision that would define his life: he apprenticed himself to the photographer Yva, the professional name of Elsie Neuländer Simon, one of Berlin’s most accomplished studio and fashion photographers. Under Yva’s tutelage, Newton absorbed the principles of lighting, composition, and the theatrical staging of the female body that would become the foundation of his own work. Yva was later deported and murdered at Auschwitz in 1942 — a fact that haunted Newton for the rest of his life and lent a dark undertow to his obsession with power, vulnerability, and the fragility of glamour.

The rise of Nazism made life in Germany impossible for the Neustädter family. In 1938, at the age of eighteen, Newton fled Berlin, travelling by ship via Trieste and Singapore. He eventually arrived in Australia, where he was briefly interned as an enemy alien before being released and settling in Melbourne. He anglicised his name to Helmut Newton, took up Australian citizenship, and began working as a fashion photographer for local magazines. In 1948, he married the actress June Browne, who would become his lifelong partner, creative collaborator, and — under the pseudonym Alice Springs — a distinguished photographer in her own right. The partnership between Newton and June was one of the most remarkable in the history of photography: she was his first editor, his most trusted critic, and, on occasion, his model, and their mutual devotion endured through decades of controversy, travel, and creative reinvention.

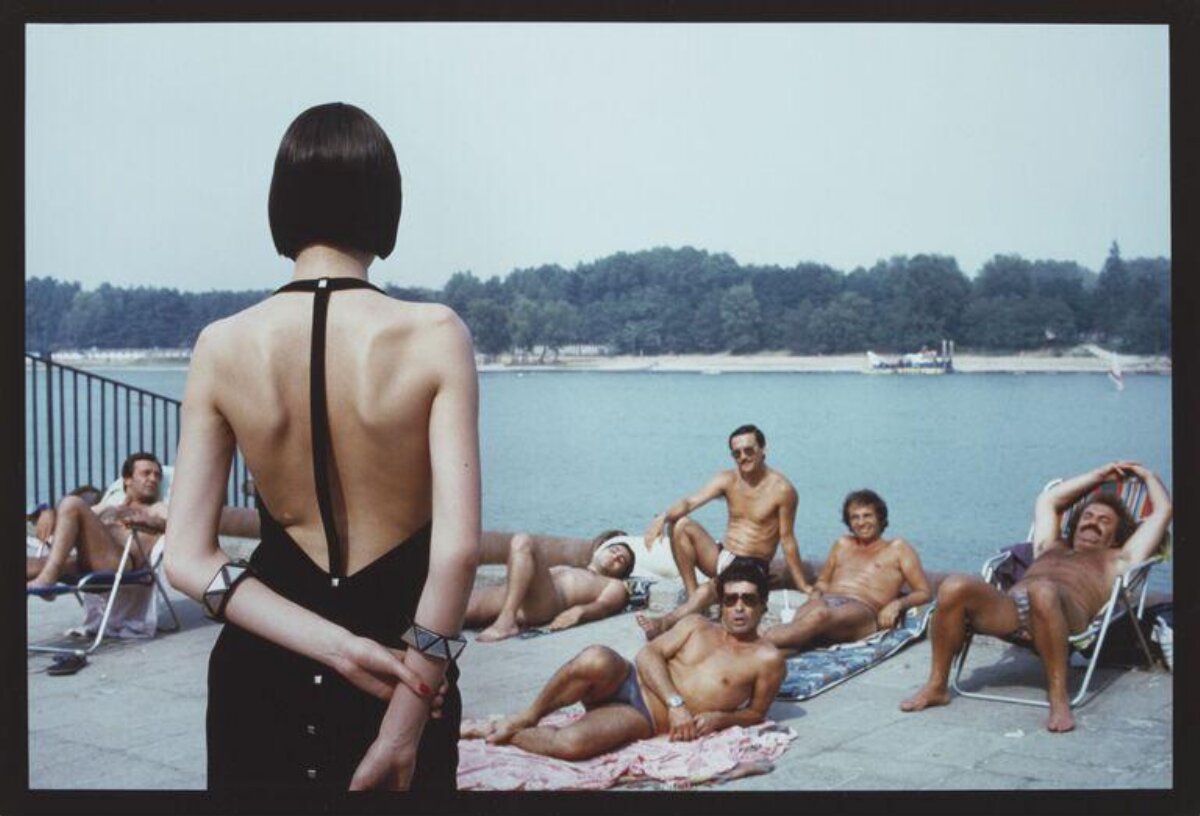

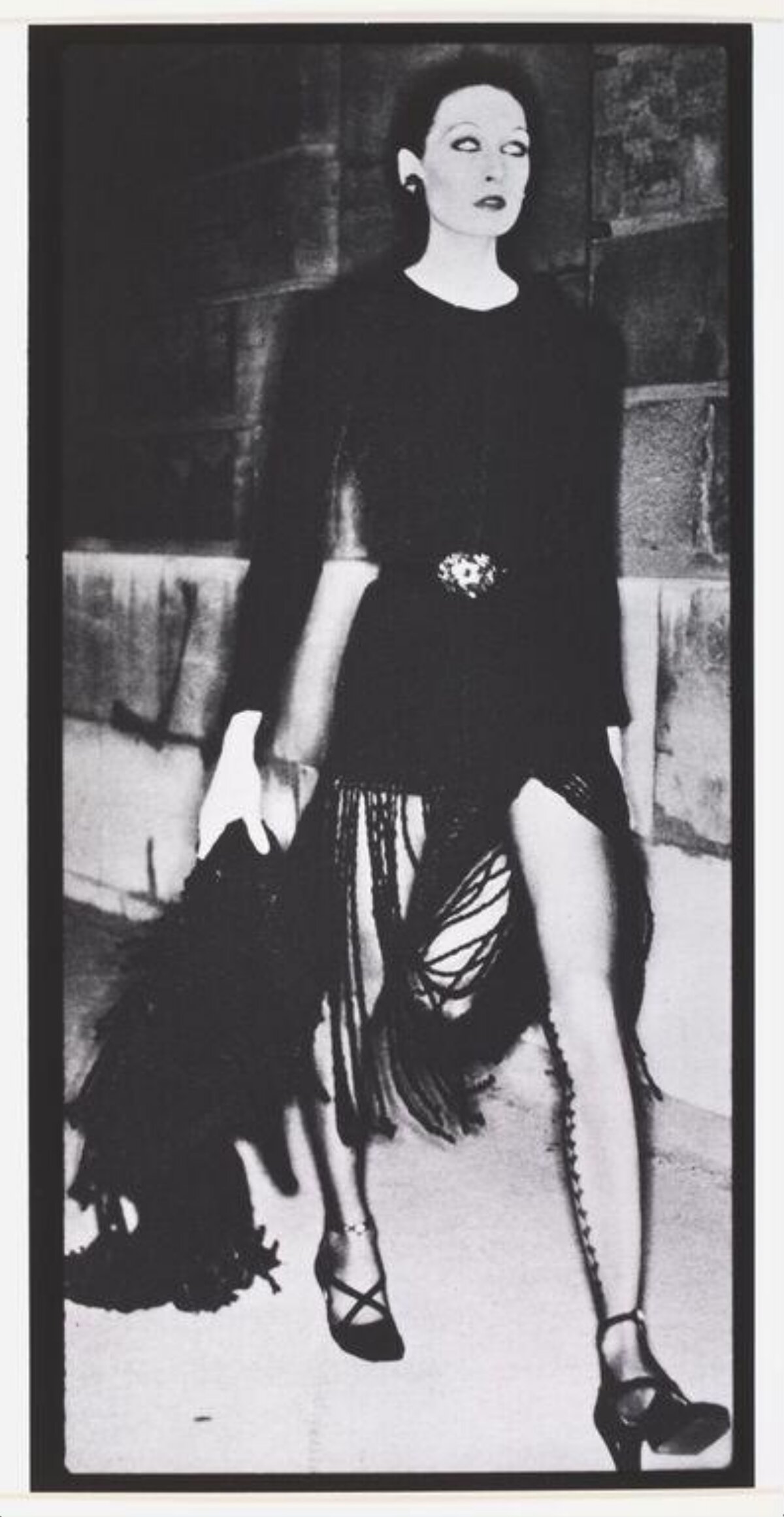

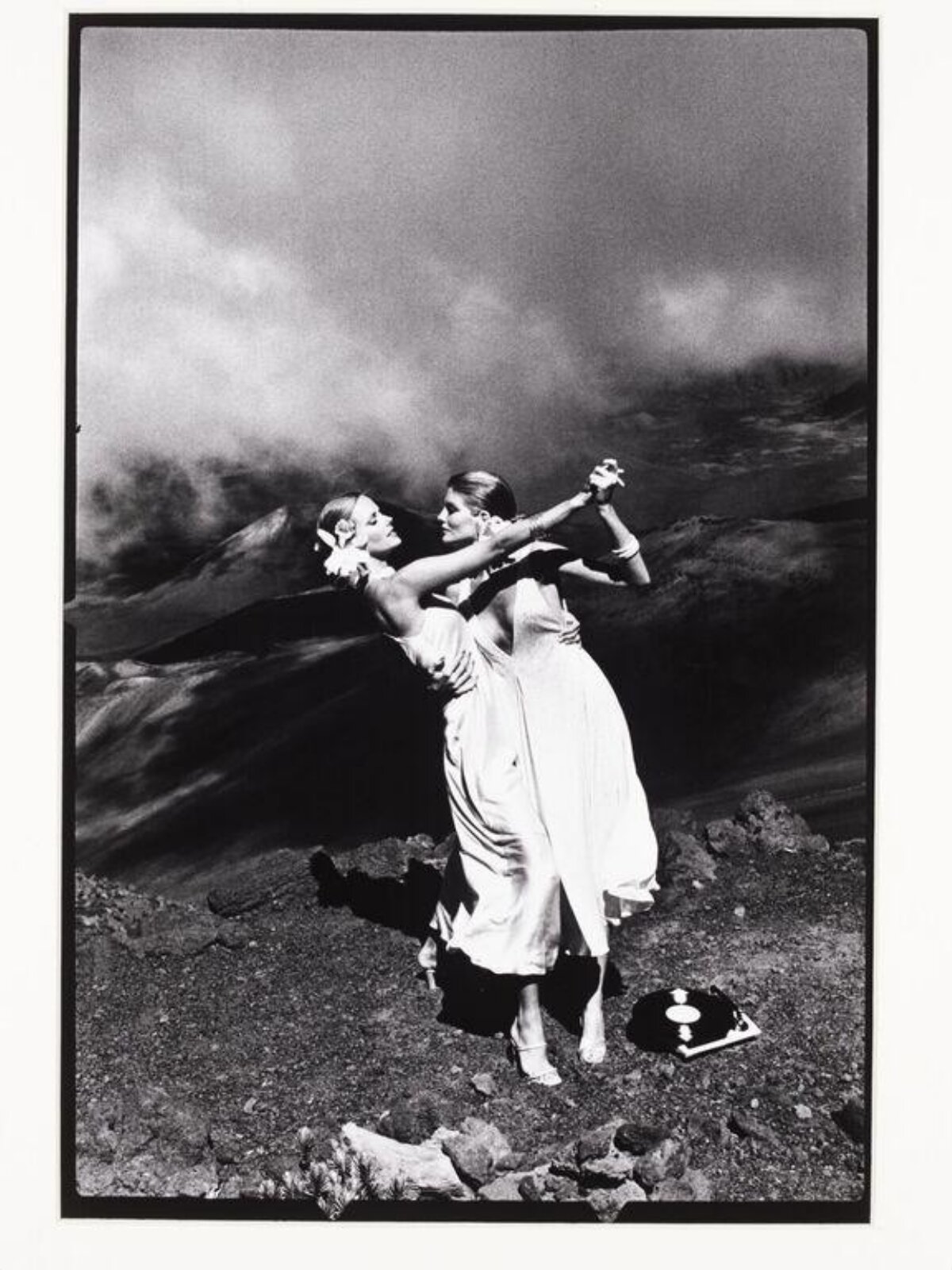

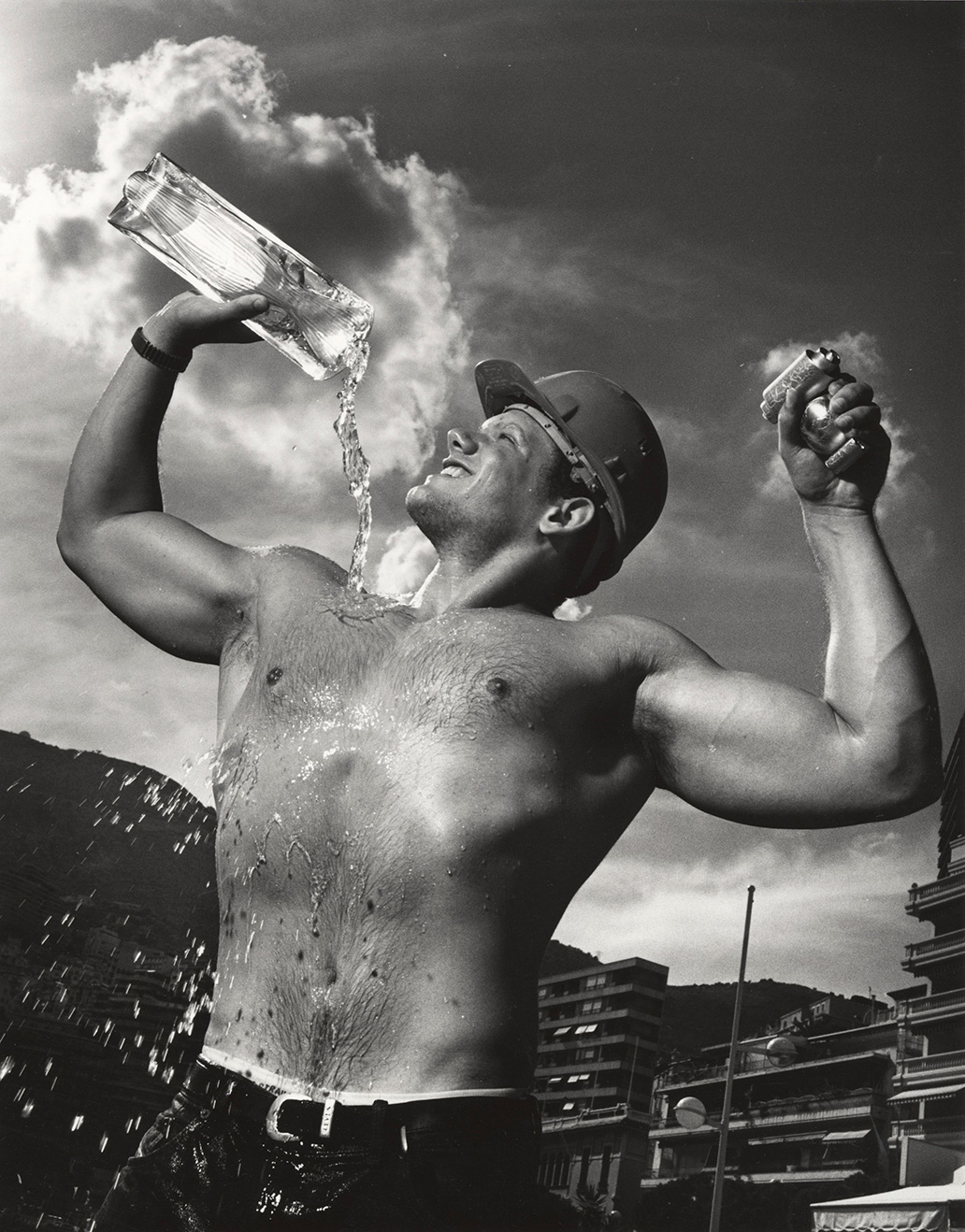

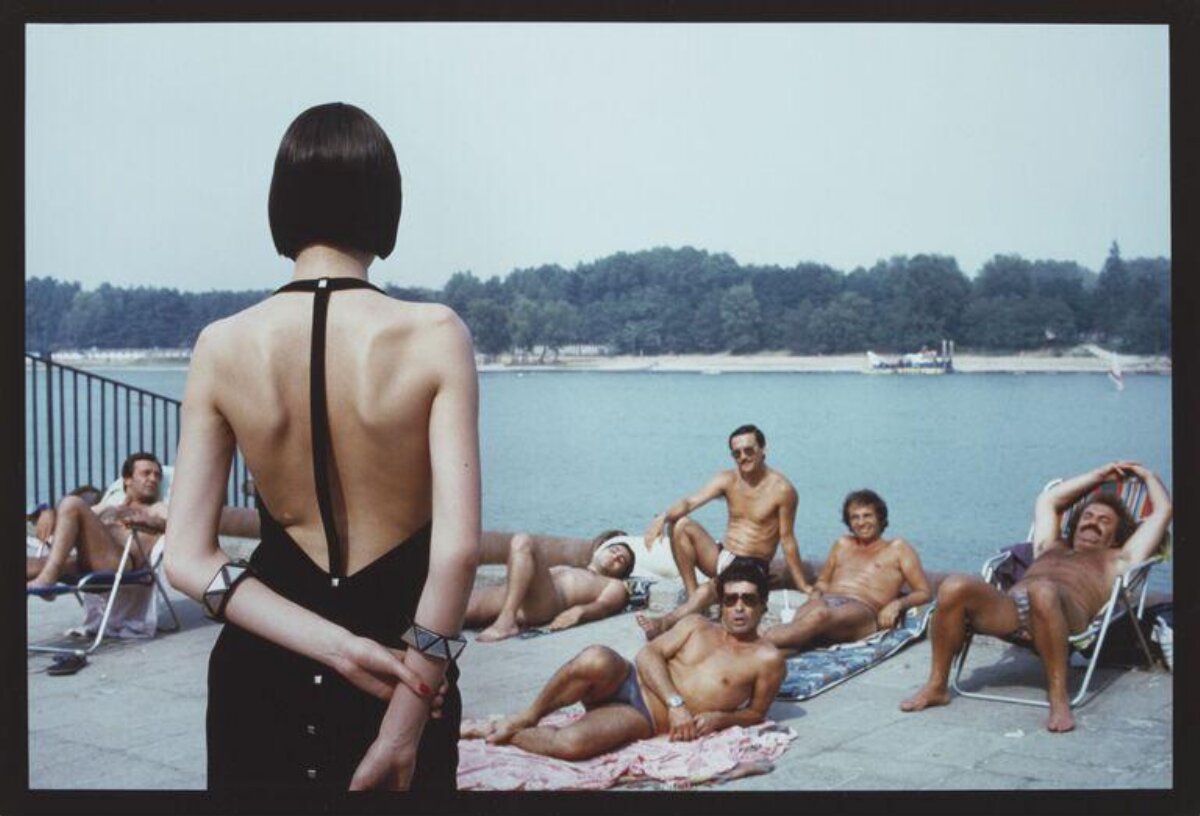

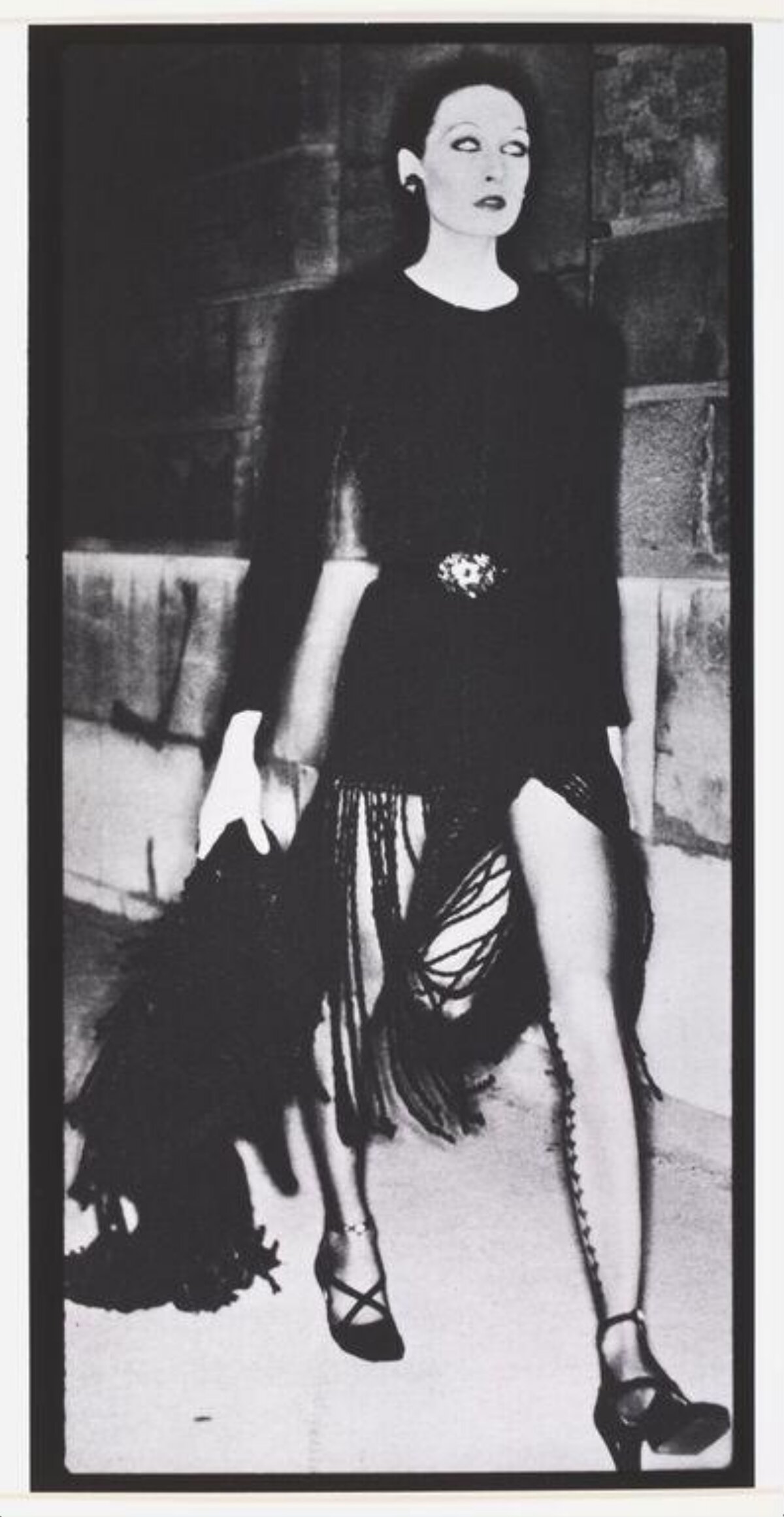

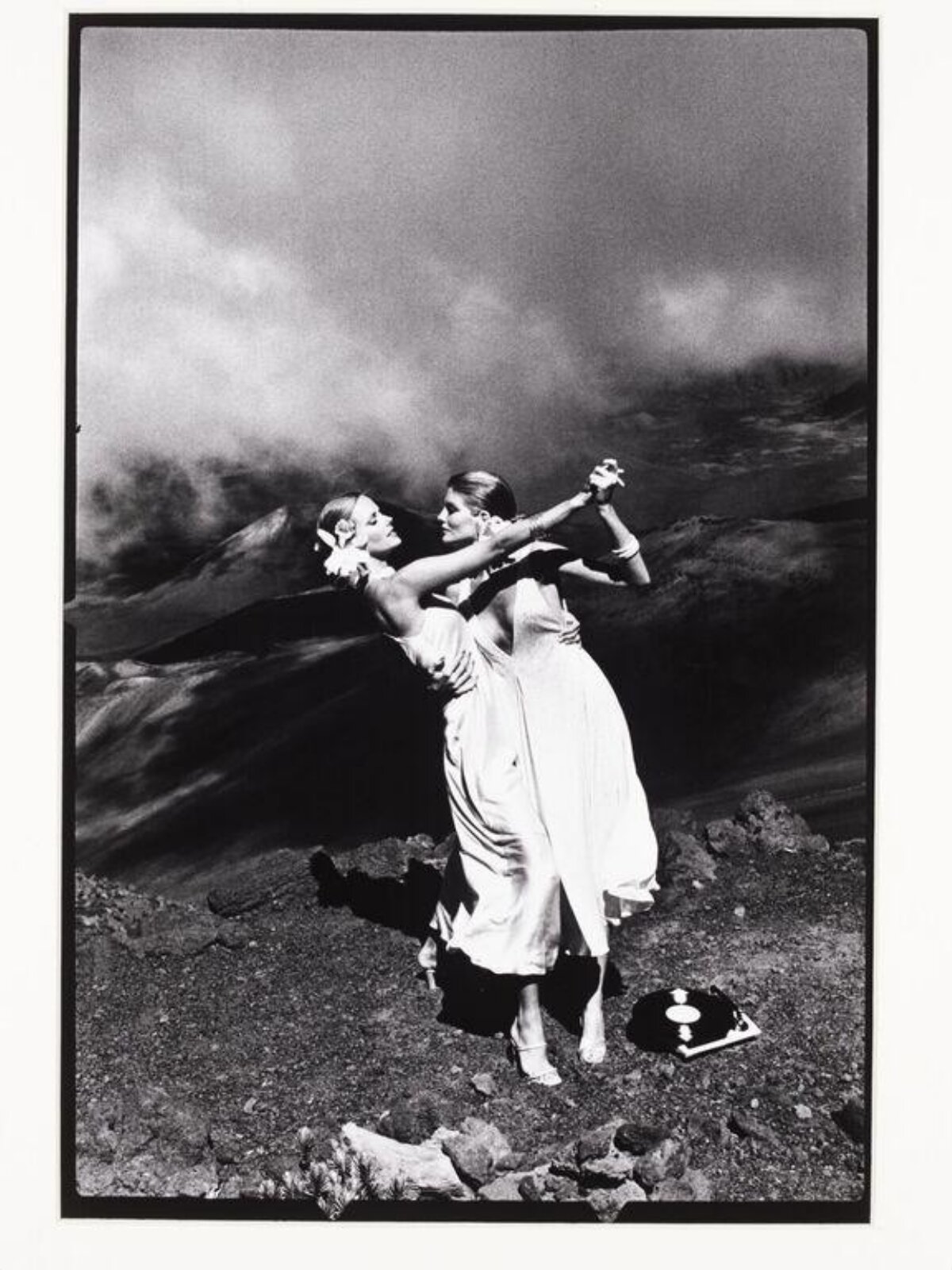

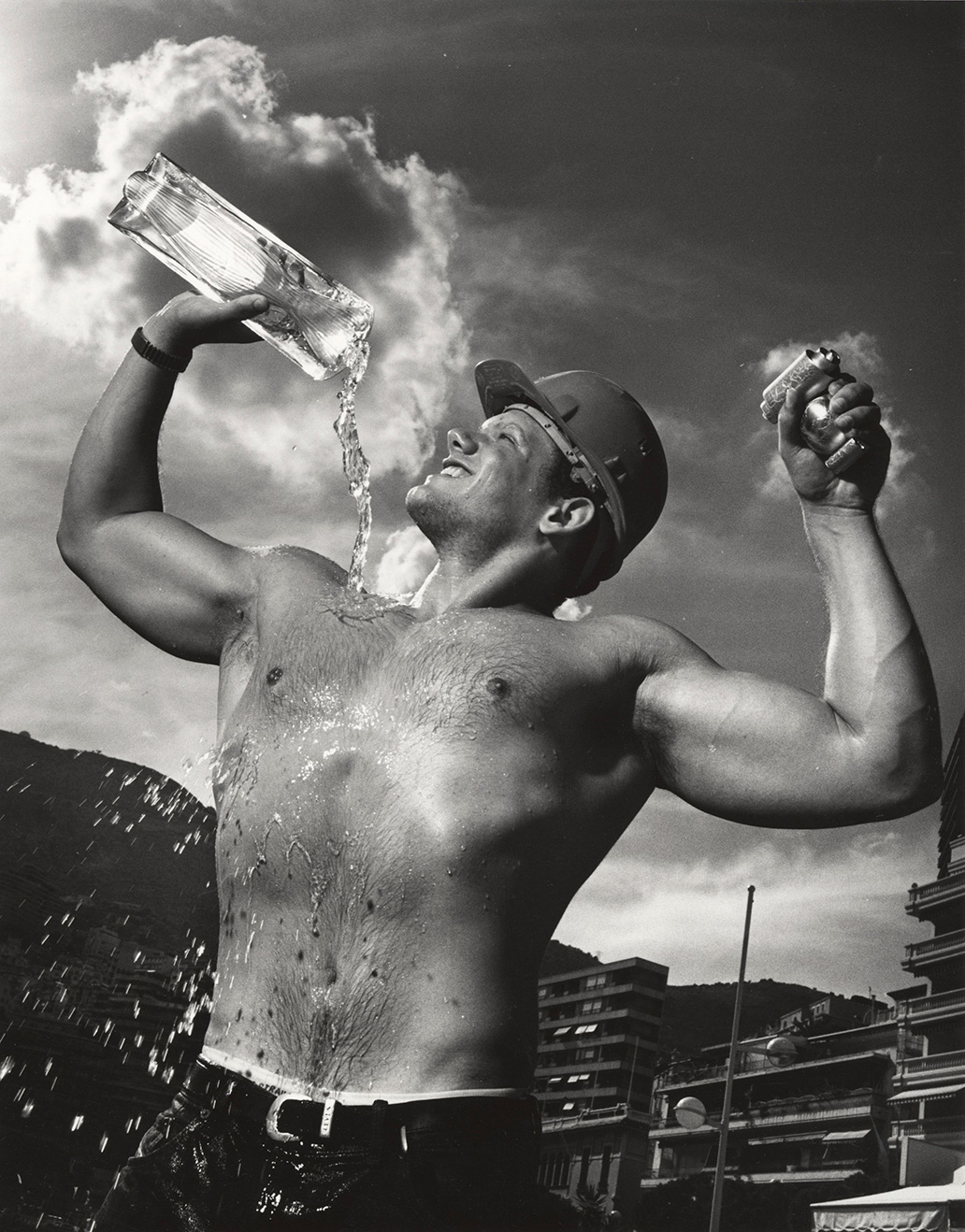

In 1961, Newton and June moved to Paris, where he began working for French Vogue under the visionary art director Francine Crescent. It was in Paris that Newton’s signature style crystallised with extraordinary speed. Where other fashion photographers of the era created images of delicate, ethereal femininity, Newton produced photographs of statuesque, commanding women who radiated authority, danger, and unabashed sexuality. His models did not pose passively; they strode, confronted, and dominated the frame. He placed them in grand hotel suites, on rain-slicked Parisian streets at night, in the back seats of limousines, and in situations that blurred the line between fashion editorial, film noir, and the imagery of fetishism. The effect was electrifying and deliberately unsettling — Newton was not interested in making women beautiful in any conventional sense, but in making them powerful, and in exploring the eroticism that power generated.

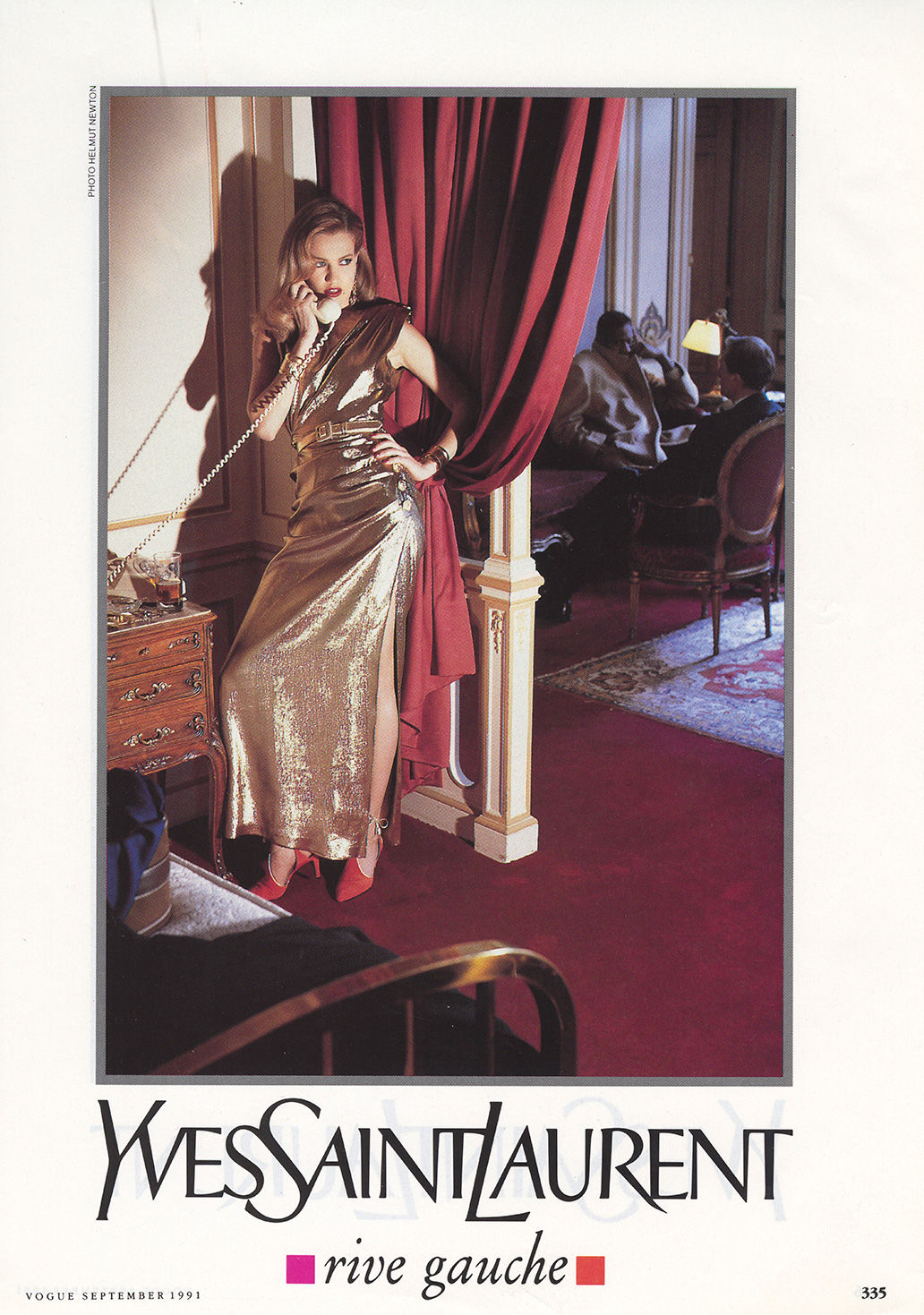

The 1975 photograph Rue Aubriot, shot for Yves Saint Laurent and French Vogue, became one of the most iconic fashion images of the twentieth century: a woman in a tailored Le Smoking suit and stilettos standing alone on a dark Parisian street, her androgynous elegance charged with an ambiguity that seemed to contain the entire history of desire and transgression. That same year, his portraits of Elsa Peretti in a rabbit-ear bodysuit for American Vogue pushed the boundaries of what mainstream fashion magazines would publish. Newton was testing limits constantly, and the magazines — seduced by the brilliance of his compositions and the commercial power of his imagery — followed him further than they had ever gone before.

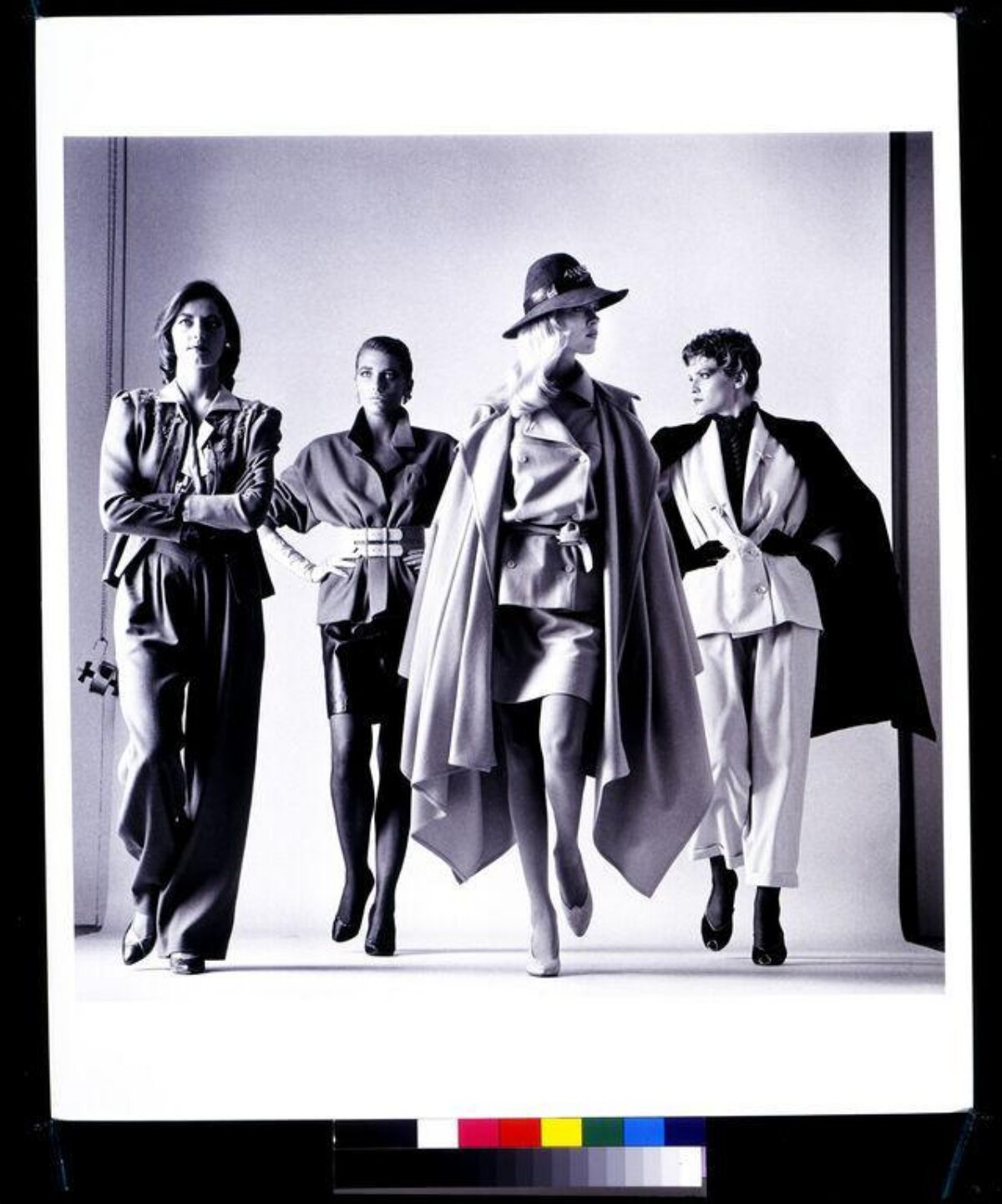

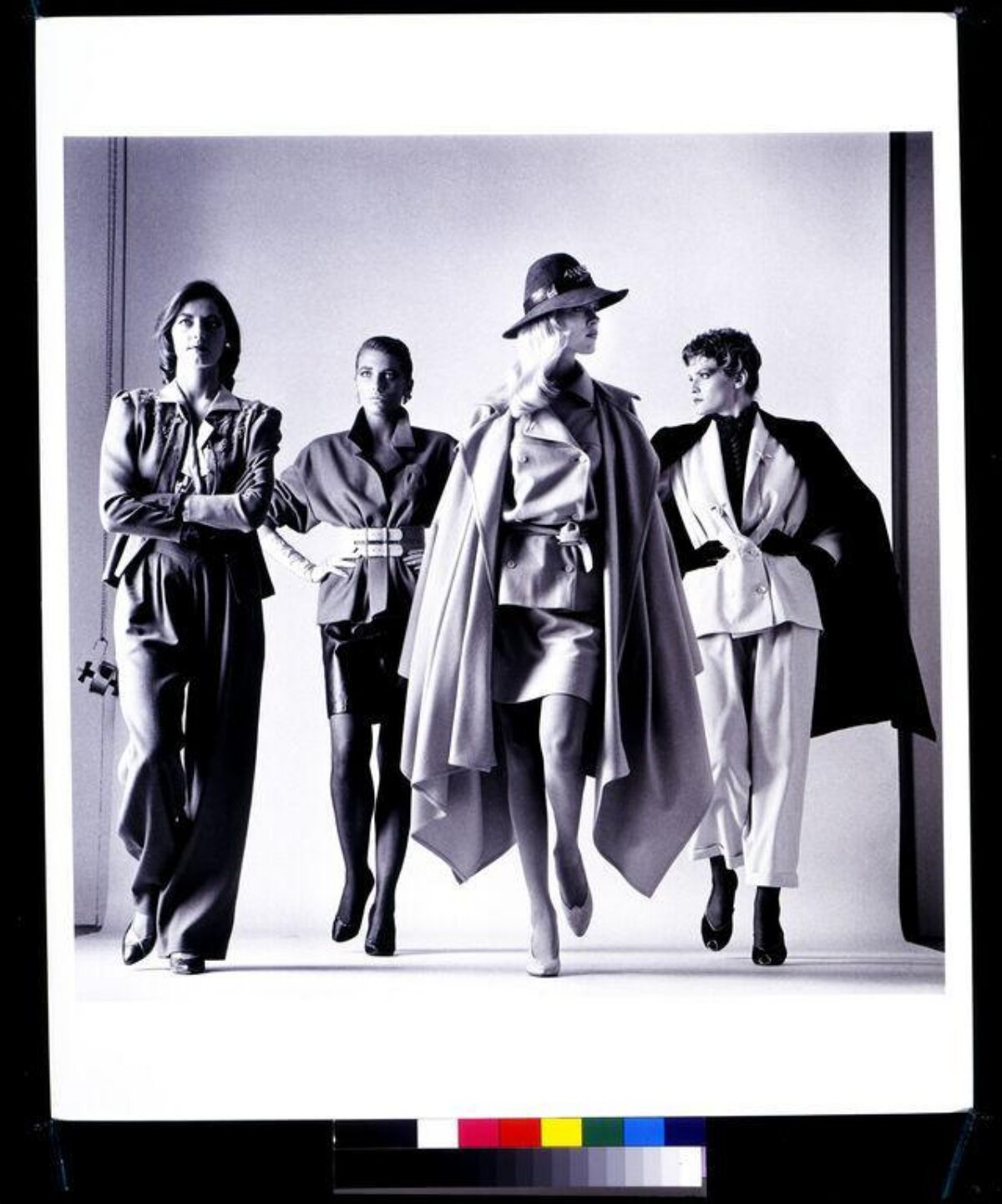

In 1976, Newton published White Women, his first major book and a landmark in the history of photography publishing. The collection announced, in unambiguous terms, the themes that would occupy him for the rest of his career: glamour and menace, nudity and power, luxury and surveillance, the voyeuristic gaze and the woman who returns it without flinching. Two years later, Sleepless Nights (1978) extended the territory with images of even greater provocation. But it was the Big Nudes series, first exhibited and published in 1981, that detonated the fiercest controversy of Newton’s career. The series presented full-length, life-size nude portraits of models wearing nothing but high heels, standing with an attitude of commanding self-possession that was simultaneously statuesque and confrontational. Alongside them, Newton created Sie Kommen (“Here They Come”), a diptych showing the same four models first naked, then identically posed in tailored business suits — a work that became one of the most debated images in the history of fashion photography.

The debate over Newton’s work was fierce and unresolved. Feminist critics accused him of objectifying women, of glamorising the structures of patriarchal power, and of aestheticising dominance and submission for the pleasure of the male gaze. Others — including many of the women who worked with him — argued precisely the opposite: that Newton’s women were agents, not objects; that they possessed a self-assurance and physical authority that subverted the very conventions of the fashion photograph; and that his images revealed, rather than concealed, the power dynamics that pervaded the world of luxury and desire. Newton himself was characteristically unrepentant. He refused to justify or explain his photographs, insisting that they spoke for themselves and that the discomfort they provoked was part of their purpose.

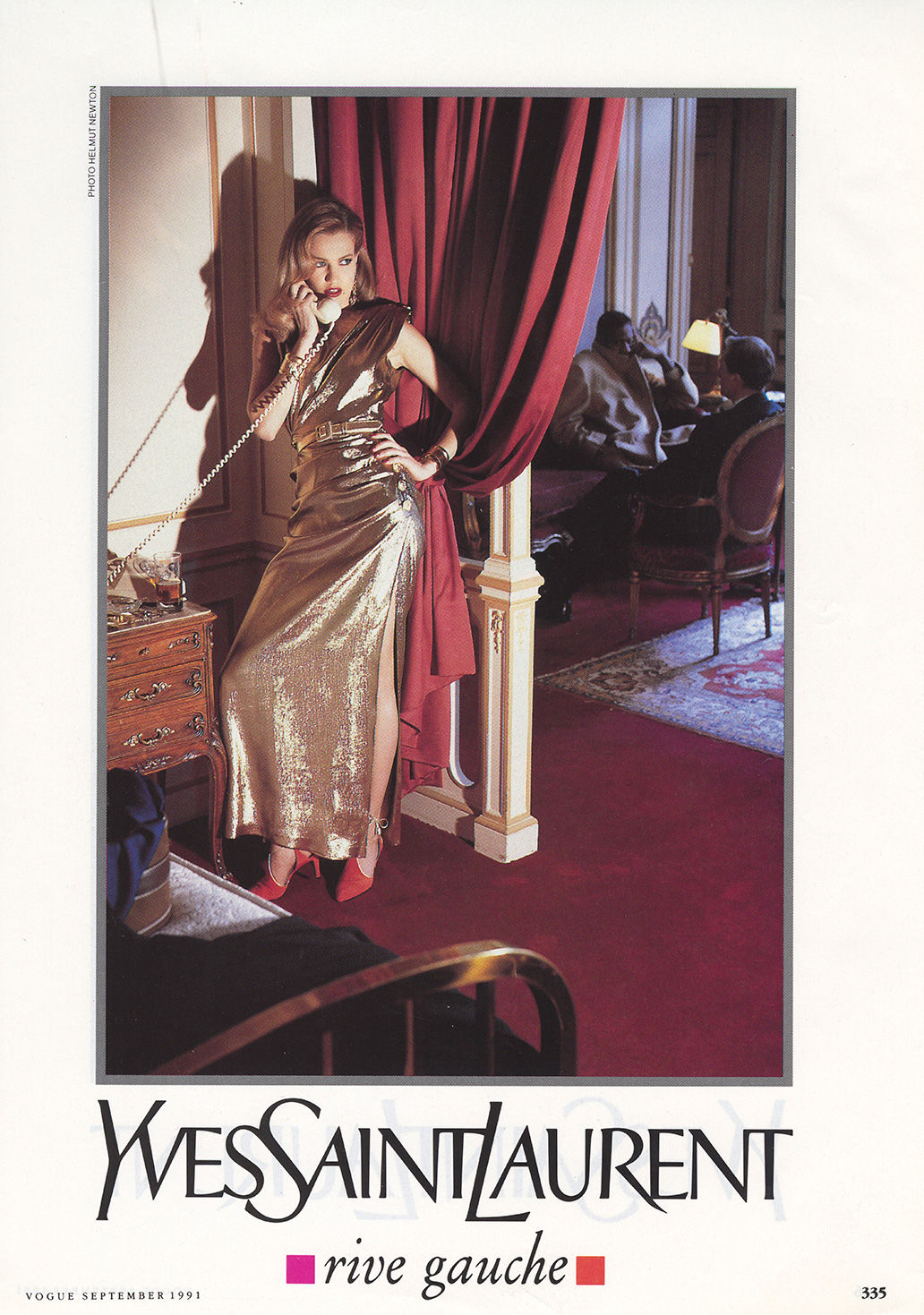

Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, Newton continued to work prolifically for all the major editions of Vogue, as well as for Vanity Fair, Elle, and numerous other publications. His celebrity portraits — of David Lynch, Margaret Thatcher, Andy Warhol, Paloma Picasso, and dozens of others — brought the same theatrical intensity and psychological edge that characterised his fashion work. In 1999, the publisher Taschen released SUMO, a monumental limited-edition retrospective that surveyed Newton’s career across 464 pages. The book weighed over thirty kilograms, came with its own Philippe Starck-designed stand, and was issued in a signed edition of ten thousand copies that sold out almost immediately. It remains one of the most valuable and sought-after photography books of the twentieth century, and it cemented Newton’s status as a cultural figure whose influence extended far beyond the pages of fashion magazines.

Helmut Newton died on January 23, 2004, following a car accident at the Chateau Marmont hotel in Los Angeles, at the age of eighty-three. He had been living between Monte Carlo, Los Angeles, and Paris for decades, restless and productive to the end. In June 2004, the Helmut Newton Foundation opened in a former Prussian officers’ casino in Berlin — the city he had fled sixty-six years earlier — housing his archive, his personal collection, and a permanent exhibition of his work alongside that of June Newton (Alice Springs). His legacy remains as provocative and contested as the photographs themselves: an oeuvre that insists on the inseparability of beauty and danger, glamour and power, desire and transgression, and that refuses to offer the viewer the comfort of a settled moral position.

Some people’s photography is an art. Not mine. Mine is a truth. I just record things as I see them. Helmut Newton

Newton’s first major book, a collection of fashion and nude photographs that announced his signature aesthetic of glamorous, empowered, and sexually confrontational women in luxurious settings.

The monumental series of life-size nude portraits of models standing in high heels with an attitude of commanding self-possession, which became Newton’s most recognised and debated body of work.

A limited-edition book of extraordinary physical scale, published by Taschen, that surveyed Newton’s career in 464 pages and weighed over thirty kilograms, becoming one of the most valuable photography books of the twentieth century.

Born Helmut Neustädter in Berlin to a prosperous Jewish family. Develops an early interest in photography.

Apprentices with the photographer Yva (Elsie Neuländer Simon), absorbing the techniques of studio and fashion photography. Yva will later be murdered at Auschwitz.

Flees Nazi Germany, travelling via Trieste and Singapore to Australia, where he is briefly interned as an enemy alien.

Opens a fashion photography studio in Melbourne. Begins working for Australian Vogue. Marries actress June Browne, who will later become the photographer Alice Springs.

Moves to Paris and begins working for French Vogue under art director Francine Crescent, rapidly establishing a reputation for provocative, cinematic fashion imagery.

Photographs Rue Aubriot for Yves Saint Laurent and French Vogue, creating one of the most iconic fashion photographs of the twentieth century.

Publishes White Women, his first major book. The controversy over his depictions of women begins in earnest.

Creates the Big Nudes and Sie Kommen series, life-sized nude portraits that provoke fierce debate about power, gender, and the male gaze.

Taschen publishes SUMO, a monumental limited-edition retrospective that becomes one of the most expensive and sought-after photography books ever produced.

Dies following a car accident in Los Angeles at the age of eighty-three. The Helmut Newton Foundation opens in Berlin, housing his archive and legacy.

Interested in discussing photography, collaboration, or just want to say hello? I’d love to hear from you.

Contact →