America's most prolific street photographer, whose restless eye and voracious appetite for the visual spectacle of everyday life produced an unparalleled catalogue of mid-century American energy, chaos, and joy.

1928, The Bronx, New York — 1984, Tijuana, Mexico — American

Garry Winogrand was born on January 14, 1928, in the Bronx, New York, into a working-class Jewish family. His father worked in the leather goods trade, and the neighbourhood in which Winogrand grew up was dense, loud, and teeming with the kind of street-level human theatre that would later become the raw material of his art. The Bronx of the 1930s and 1940s was a place where life happened outdoors, on stoops and sidewalks and in crowded parks, and from an early age Winogrand absorbed the rhythm of public life with an intensity that never left him. He would grow into the most compulsive photographer America has ever produced, a man for whom the act of looking through a viewfinder was as involuntary as breathing.

After serving in the United States Air Force during the mid-1940s, Winogrand enrolled at City College of New York on the GI Bill, initially studying painting. He soon transferred to Columbia University to continue his art studies, but it was a class at the New School for Social Research under the legendary art director Alexey Brodovitch that changed the course of his life. Brodovitch, who had shaped the visual identity of Harper's Bazaar and mentored a generation of photographers, taught Winogrand to see photography not as a mechanical recording device but as a medium capable of surprise, spontaneity, and raw visual power. By the early 1950s, Winogrand had abandoned painting altogether and committed himself entirely to the camera.

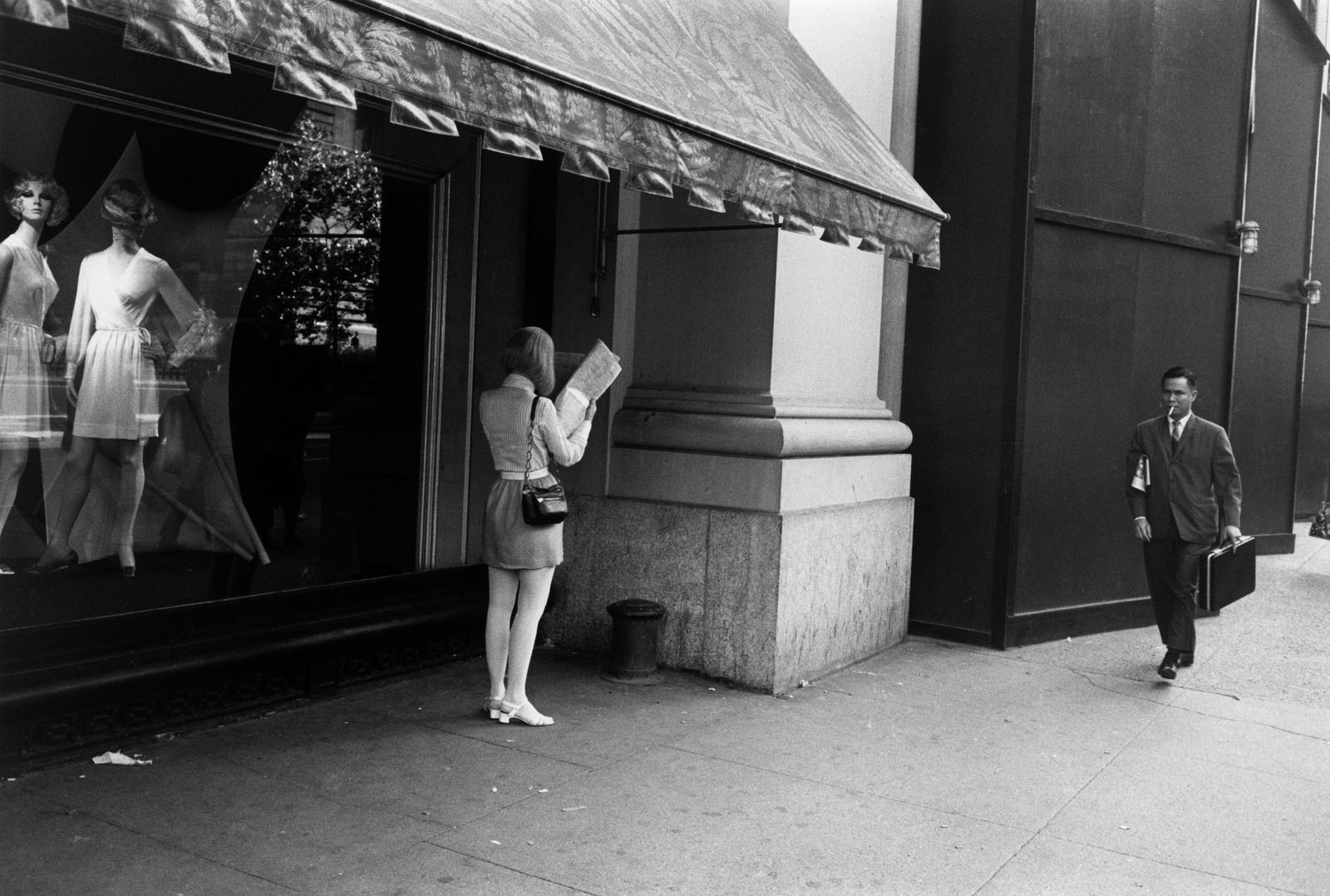

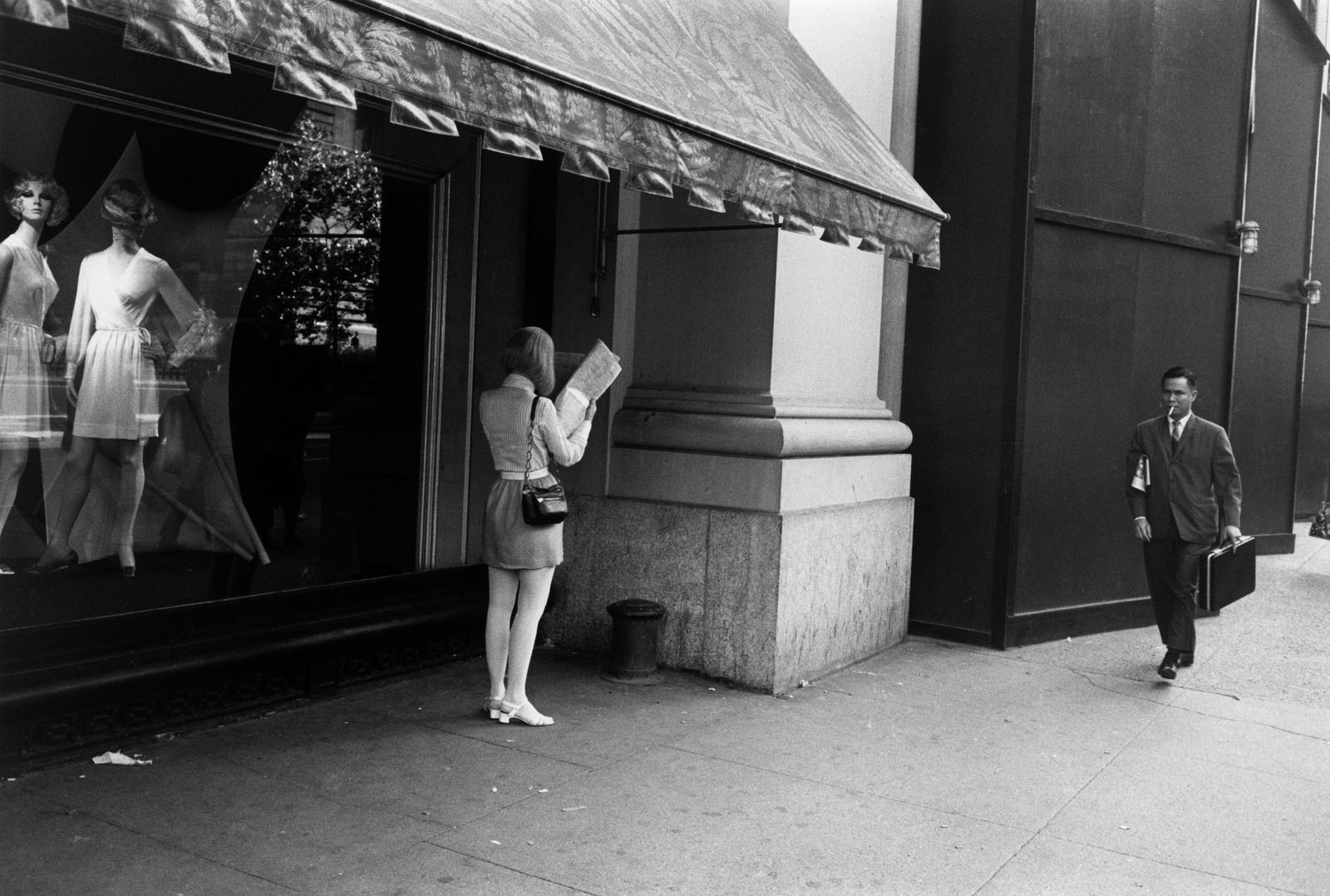

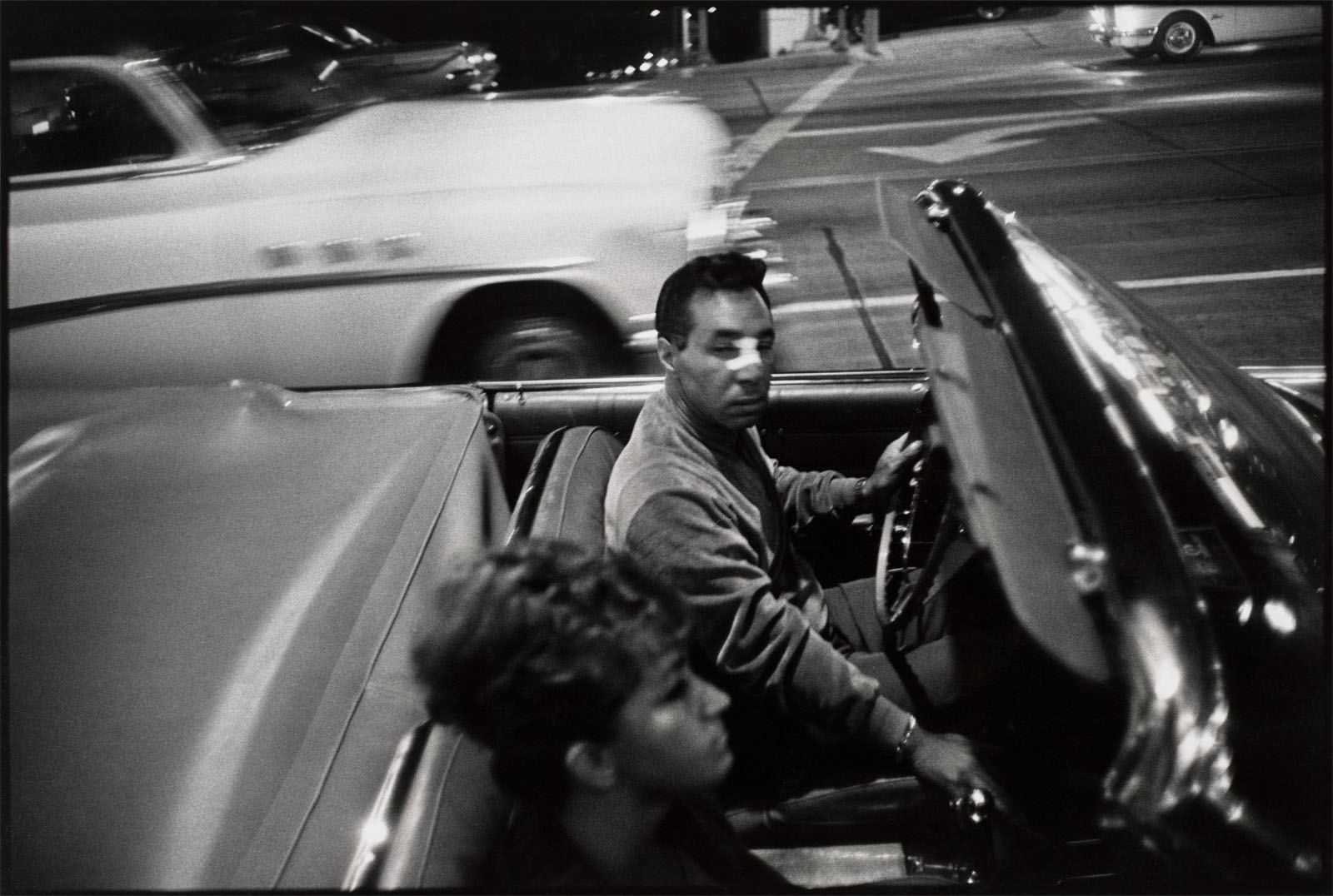

Throughout the 1950s, Winogrand worked as a freelance photojournalist and advertising photographer, shooting assignments for magazines such as Collier's, Redbook, Sports Illustrated, and various other publications. But his real work happened on the streets. He walked the avenues of Manhattan with a wide-angle lens and a voracious appetite for the visual chaos of American life. His influences were evident: Walker Evans had shown that vernacular America was worthy of serious artistic attention, and Robert Frank had demonstrated that the personal, subjective, and deliberately imperfect photograph could carry more emotional truth than any technically polished image. Winogrand took these lessons and pushed them further, developing a style that was more aggressive, more physical, and more relentlessly energetic than anything that had come before.

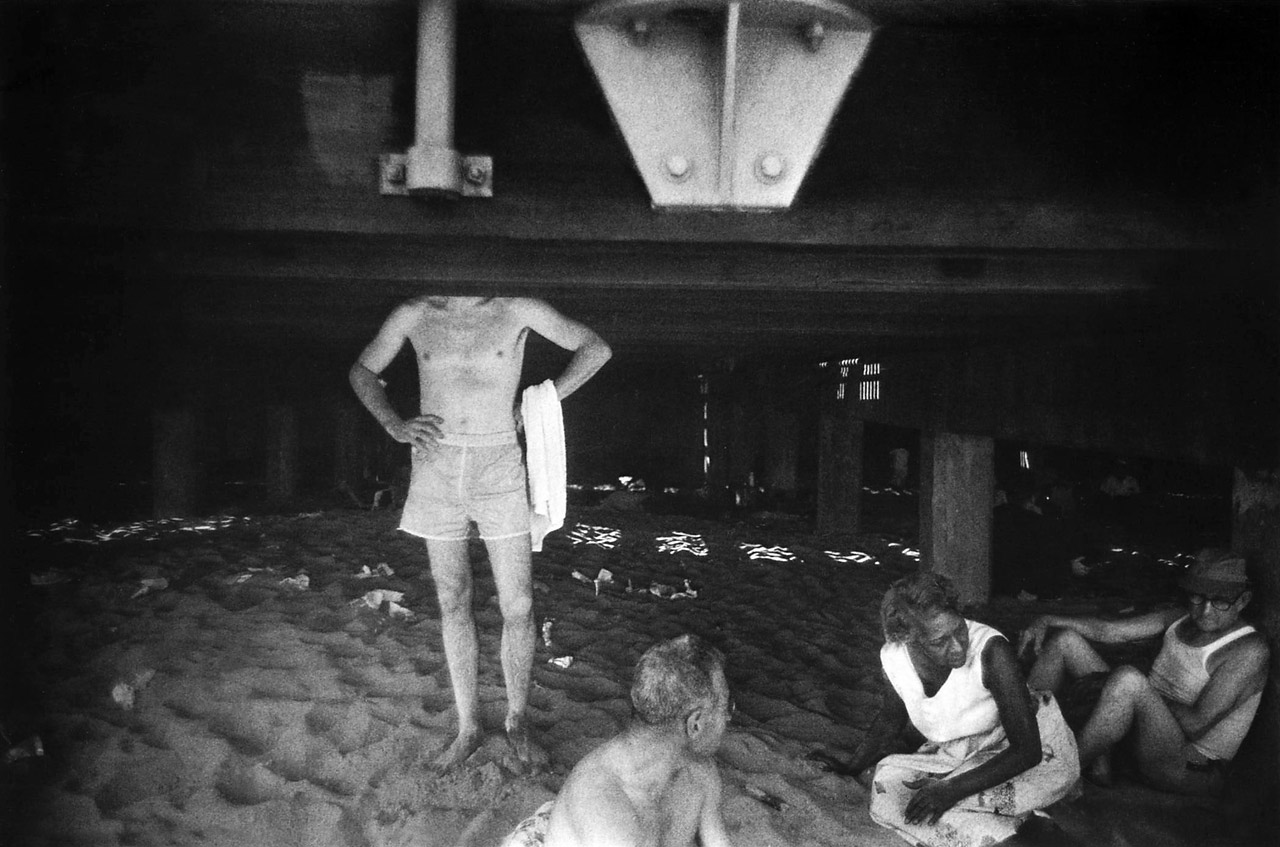

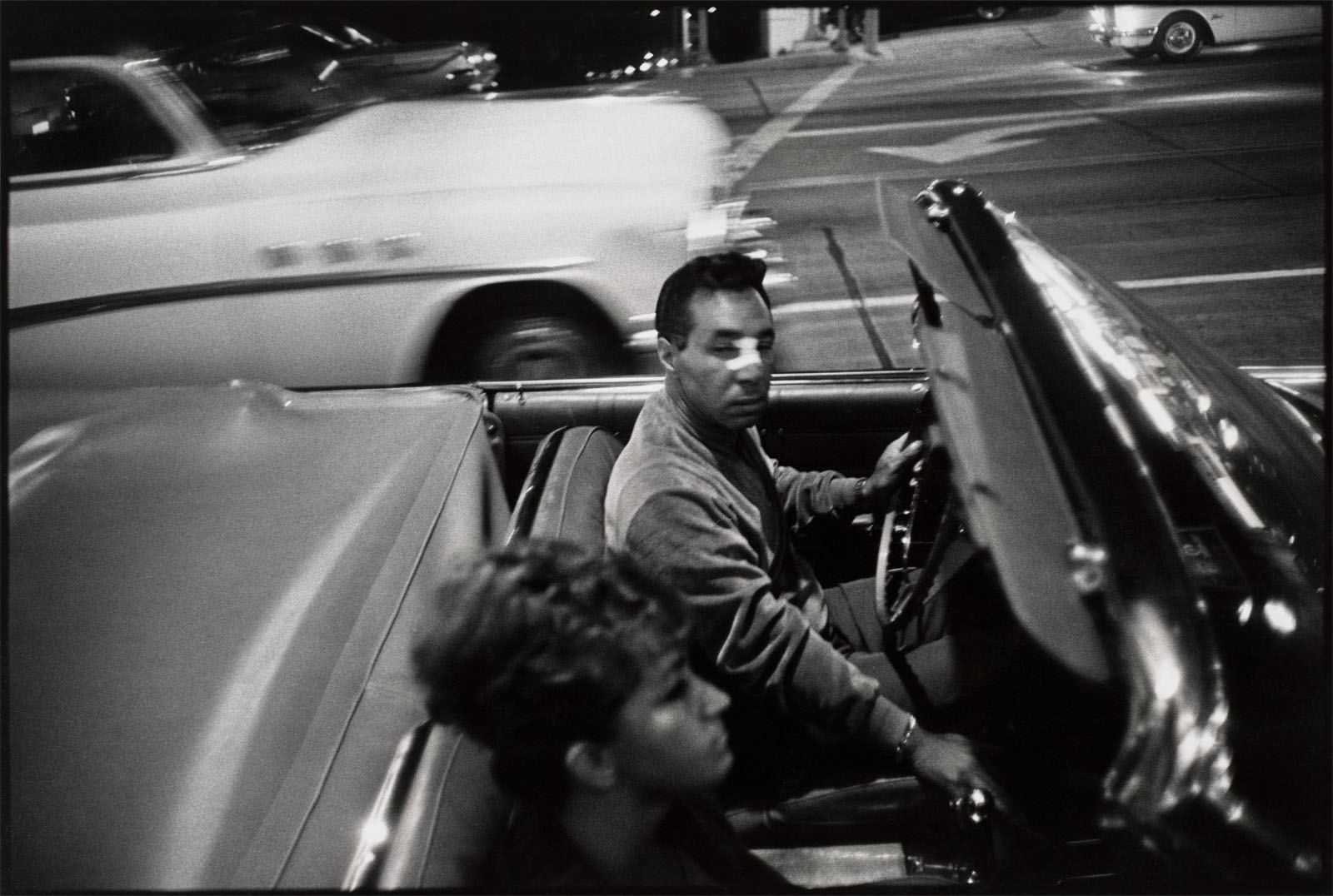

What set Winogrand apart was the sheer volume and velocity of his seeing. He shot constantly, compulsively, often exposing dozens of rolls of film in a single day. He worked with a Leica rangefinder, typically loaded with Tri-X film, and he frequently shot from the hip or at oblique angles, tilting the camera to create frames that pitched and rolled with the energy of the street. His photographs are crowded with bodies, gestures, glances, and collisions of form. Figures lean into one another or pull apart. The horizon tilts. Faces are caught in fleeting expressions that hover between comedy and pathos. There is a sense in his best work of life happening faster than anyone can comprehend it, and of the photograph as a desperate, joyful attempt to hold on to a fragment of that rush.

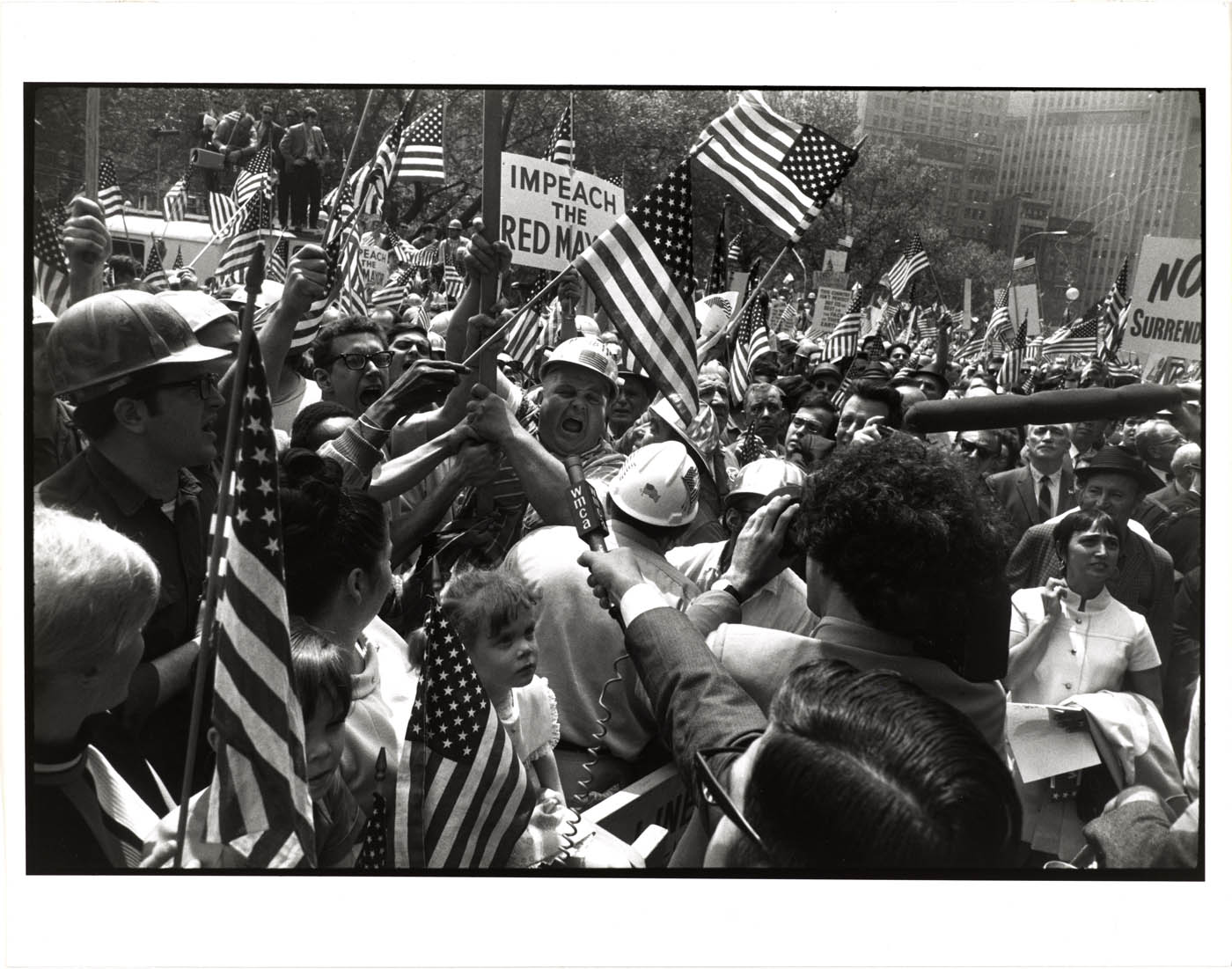

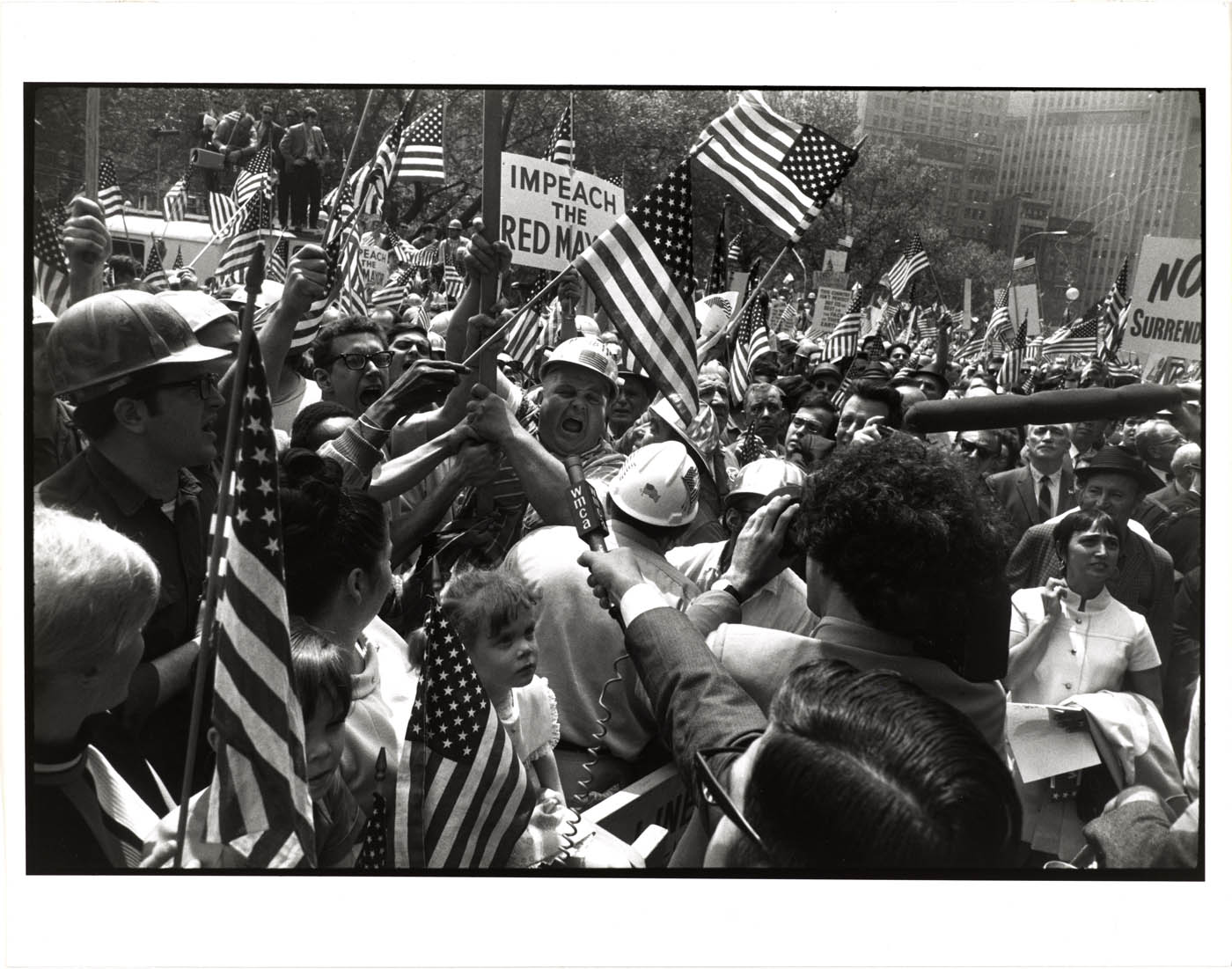

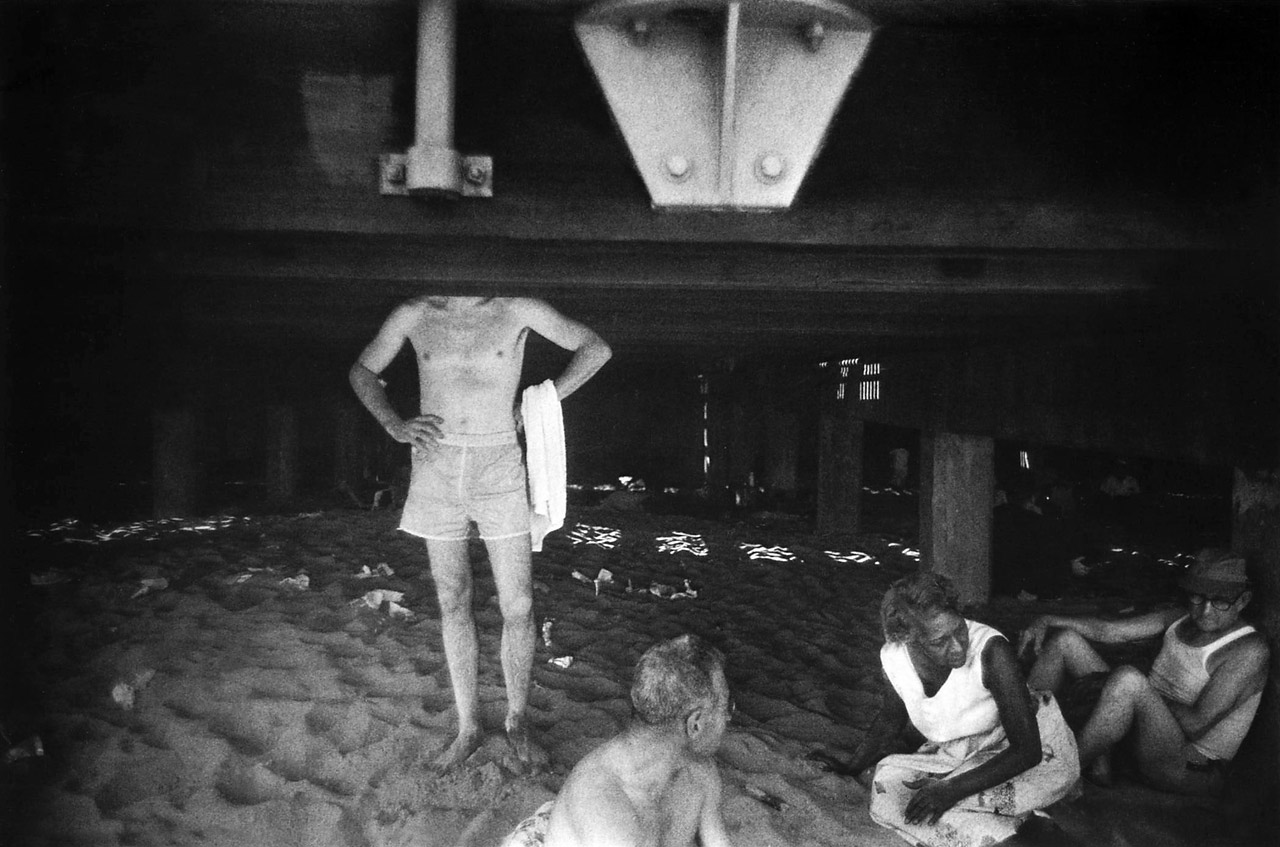

In 1964, Winogrand received his first Guggenheim Fellowship, which allowed him to pursue a project photographing the effect of the media on public events. He would go on to receive two more Guggenheim Fellowships, a distinction matched by very few photographers. In 1967, he was included in the landmark New Documents exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, curated by John Szarkowski, alongside Diane Arbus and Lee Friedlander. The exhibition announced a new direction in American photography, one that treated the photographer's personal encounter with the world as its primary subject. Winogrand's contribution was unmistakable: raw, restless, and teeming with the disorderly vitality of the American street. His major books cemented his reputation. The Animals, published in 1969, presented visitors at the Bronx Zoo and the Coney Island Aquarium with a mordant wit that blurred the line between the watchers and the watched. Women Are Beautiful, published in 1975, was a collection of candid photographs of women on New York streets that drew both praise for its energy and criticism for its unexamined male gaze. Public Relations, published in 1977, examined the strange theatre of press conferences, demonstrations, and media events in an America increasingly obsessed with spectacle.

In the early 1970s, Winogrand began teaching at various institutions, and in 1973 he moved from New York, first to Los Angeles and then to Austin, Texas, where he joined the faculty at the University of Texas. The move coincided with a period of intensifying creative output but also growing disorder. Winogrand was shooting more film than ever, but he was falling further and further behind in processing and editing his work. Rolls accumulated by the hundreds, then by the thousands, exposed but undeveloped, as though the act of photographing had become detached from any interest in the resulting images. Friends and colleagues watched with a mixture of admiration and concern as the gap between his shooting and his seeing widened into a chasm.

On March 19, 1984, Garry Winogrand died of gallbladder cancer in Tijuana, Mexico. He was fifty-six years old. What he left behind was staggering in its scale: approximately 2,500 rolls of undeveloped film, 6,500 rolls of developed but unexamined negatives, and roughly 3,000 rolls of contact-printed but unedited work. It was one of the largest unprocessed photographic archives in history, a monument to both creative abundance and a kind of compulsion that had outpaced all possibility of curation. The task of processing this vast legacy fell to John Szarkowski and later to other curators and scholars, who have spent decades sifting through the material.

Winogrand's posthumous reputation has only grown. Exhibitions and publications drawn from his archive continue to reveal new dimensions of his achievement, and the sheer volume of his output ensures that the process of discovery is far from complete. He remains a towering figure in the history of street photography, not only for the brilliance of his individual images but for the philosophical intensity he brought to the act of looking. For Winogrand, photography was not about making beautiful pictures or telling stories or advancing arguments. It was about the irreducible mystery of appearances, the way the world looked when it was translated through a lens onto a strip of silver halide. He photographed, as he once said, to find out what something would look like photographed, and in that circular, endlessly curious formulation lies the essence of an artist who could never see enough.

I photograph to find out what something will look like photographed. Garry Winogrand

A provocative study of visitors at the Bronx Zoo and the Coney Island Aquarium, exploring the uneasy boundary between human and animal behaviour with wit and disquieting energy.

A controversial collection of candid photographs of women on New York streets, praised for its vitality and criticised for its male gaze, embodying the tensions of its era.

Photographs of press conferences, demonstrations, and media events that examined America's growing obsession with spectacle, publicity, and the performance of public life.

Born in the Bronx, New York. Grows up in a working-class neighbourhood; his father is a leather worker.

Begins studying painting at City College of New York on the GI Bill after serving in the United States Air Force.

Studies under Alexey Brodovitch at the New School for Social Research, turning decisively from painting to photography.

Begins working as a freelance photojournalist and advertising photographer while pursuing personal street photography.

Receives his first Guggenheim Fellowship. Photographs extensively at the New York World's Fair.

Featured in the landmark New Documents exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, curated by John Szarkowski, alongside Diane Arbus and Lee Friedlander.

Publishes The Animals, his first major book, to critical acclaim.

Receives a third Guggenheim Fellowship. Moves to Los Angeles and later to Austin, Texas, to teach at the University of Texas.

The Museum of Modern Art exhibits Public Relations, cementing his reputation as a major figure in American photography.

Dies of gallbladder cancer in Tijuana, Mexico, at the age of fifty-six, leaving behind thousands of rolls of unprocessed film that constitute one of photography's great unfinished archives.

Interested in discussing photography, collaboration, or just want to say hello? I’d love to hear from you.

Contact →