William Eugene Smith was born in Wichita, Kansas, in 1918, and from his earliest years demonstrated an intensity of purpose that would define both the brilliance and the turbulence of his life. His father, a grain dealer, committed suicide when Eugene was eighteen, a trauma that left a lasting mark on the young man. Smith began photographing for local newspapers while still in high school, and by the age of nineteen he had moved to New York City, determined to pursue photojournalism at the highest level. He studied briefly at the New York Institute of Photography but was largely self-taught, driven by an almost obsessive desire to perfect both his technique and his vision.

Smith's early career was spent working for Newsweek and then Life magazine, the great American picture weekly that provided the ideal platform for his ambitions. It was at Life that Smith began to develop the extended photo essay — a form he would reinvent and elevate to an art. Unlike the single iconic image favoured by most photojournalists, Smith conceived of his assignments as narrative sequences, carefully structured and printed to convey not just information but emotional and moral truth. He was a perfectionist in the darkroom, spending hours burning and dodging his prints to achieve the luminous, almost painterly quality that became his hallmark.

During the Second World War, Smith served as a combat photographer in the Pacific theatre, covering the battles of Saipan, Iwo Jima, and Okinawa. His war photographs are among the most searing ever made, unflinching in their depiction of suffering and death yet composed with a formal beauty that elevated them beyond mere reportage. On Okinawa in May 1945, Smith was gravely wounded by mortar shrapnel, sustaining injuries to his face, hands, and body that required over thirty operations and two years of painful recovery. The photograph he made upon his return to photography — The Walk to Paradise Garden, showing his two small children walking hand in hand into a sunlit clearing — became one of the most celebrated images of hope and renewal in the medium's history.

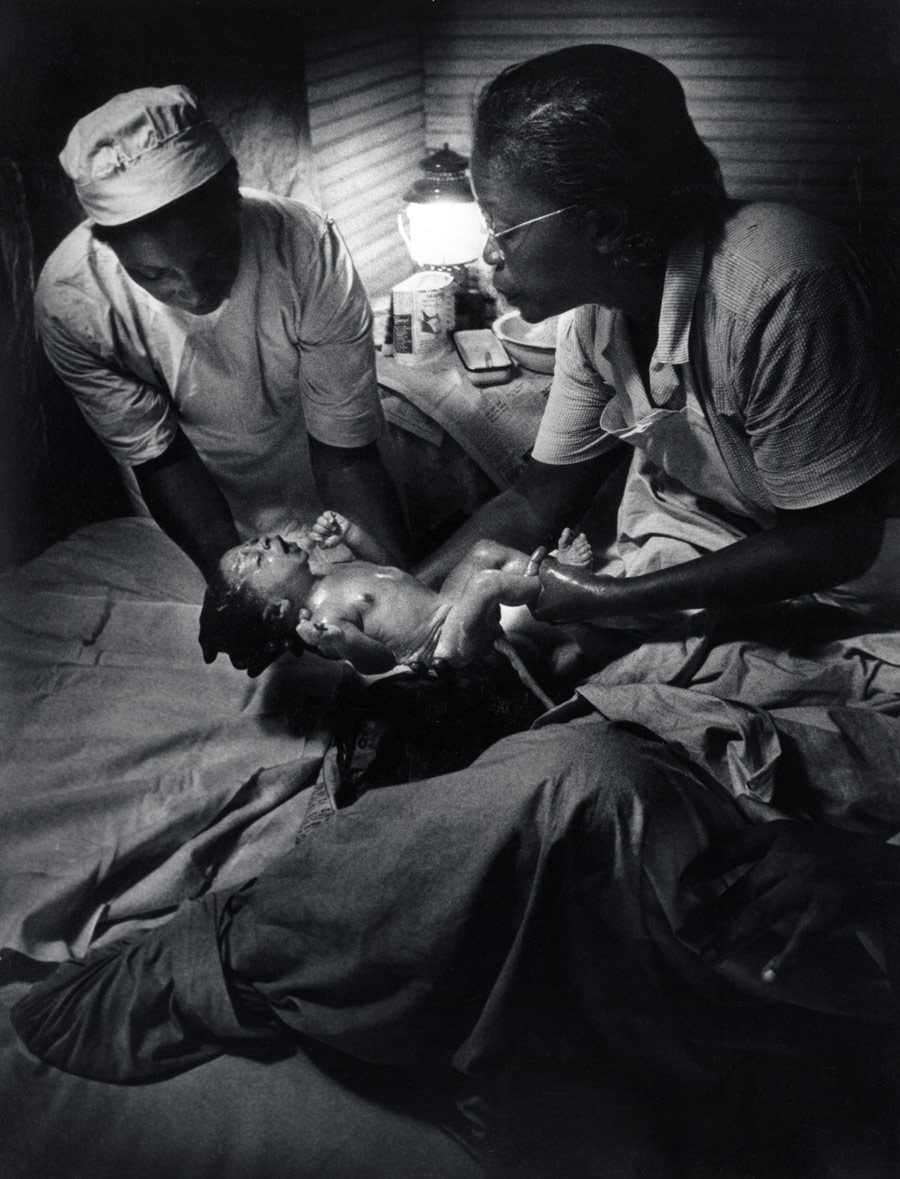

Between 1948 and 1954, Smith produced for Life magazine a series of photo essays that remain unsurpassed in their ambition, their emotional depth, and their formal achievement. Country Doctor (1948) followed Dr. Ernest Ceriani through his exhausting rounds in the small town of Kremmling, Colorado, creating an intimate portrait of rural medical practice. Spanish Village (1951) documented the lives of peasants in the impoverished village of Deleitosa with a gravity and compassion that recalled the paintings of Goya. Nurse Midwife (1951) portrayed Maude Callen, a Black nurse midwife in rural South Carolina, with such power that readers of Life donated enough money to build her a clinic.

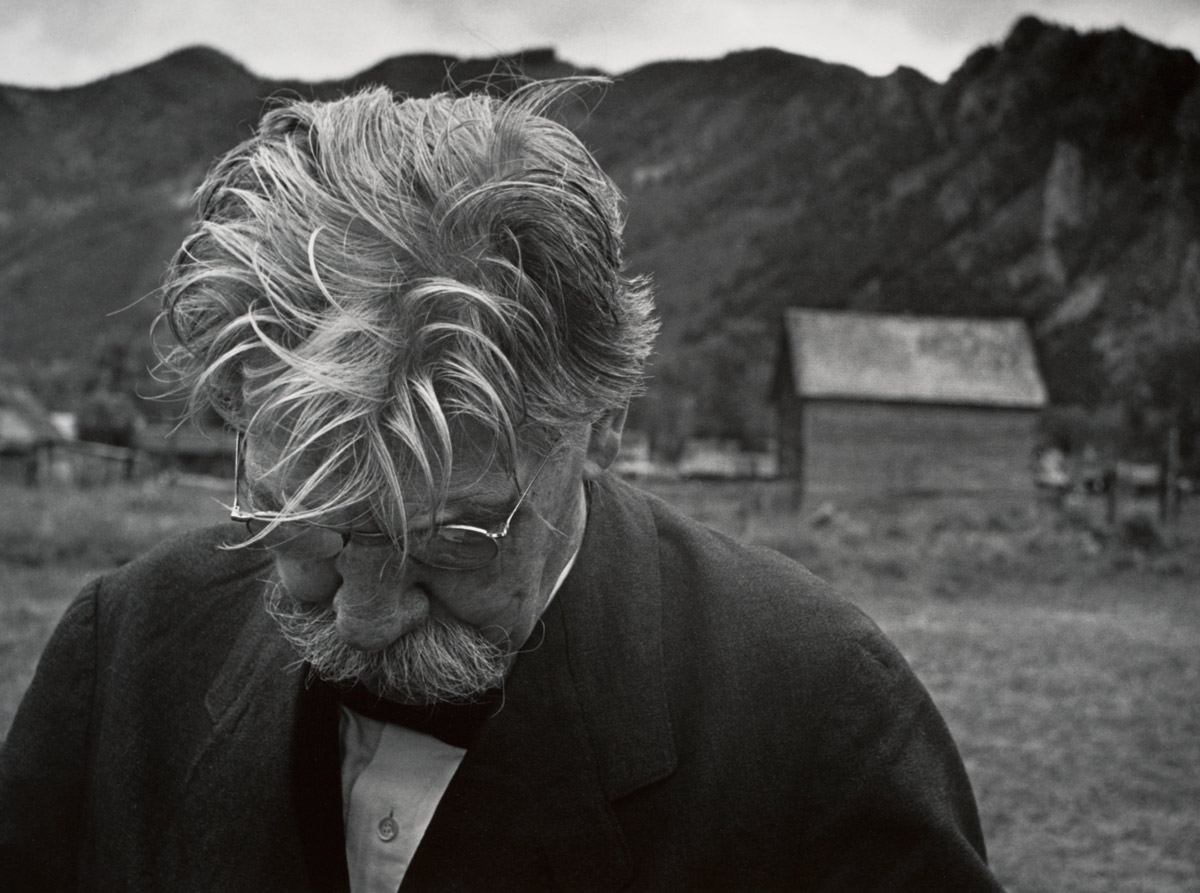

Smith's relationship with Life was stormy. He fought constantly with editors over the selection, sequencing, and cropping of his images, insisting on a degree of creative control that the magazine's editorial structure could not easily accommodate. In 1954, after a bitter dispute over the layout of his essay on Albert Schweitzer, Smith resigned from Life and undertook what he intended as his masterwork: a massive photographic study of the city of Pittsburgh. What was initially conceived as a three-week assignment stretched into three years of obsessive work, producing thousands of negatives but never reaching the definitive form Smith envisioned. The Pittsburgh project became both his most ambitious undertaking and his most painful failure, a monument to the impossibility of encompassing the totality of a city in photographs.

In 1971, Smith and his wife, Aileen Mioko Smith, moved to the fishing village of Minamata, Japan, to document the devastating effects of industrial mercury poisoning caused by the Chisso Corporation. Over three years, the Smiths lived among the victims, photographing their suffering, their resilience, and their struggle for justice with an intimacy and moral urgency that recalled Smith's finest work for Life. The resulting images, particularly the photograph of Tomoko Uemura being bathed by her mother, became powerful symbols of corporate negligence and environmental destruction, and helped bring international attention to the Minamata disaster.

During the Minamata project, Smith was attacked by Chisso employees and sustained injuries that further damaged his already fragile health. He and Aileen returned to the United States, and the Minamata photographs were published as a book in 1975. By this time, Smith's health had been ravaged by years of physical injury, amphetamine use, and the relentless demands he placed upon himself. He suffered a stroke in 1977 and died in Tucson, Arizona, on 15 October 1978, at the age of fifty-nine.

Smith's legacy is immense and complex. He demonstrated that photojournalism could aspire to the condition of art without sacrificing its commitment to truth. His photo essays established a model of extended, deeply immersive documentary work that influenced generations of photographers, from Sebastiao Salgado to James Nachtwey. His insistence on creative control anticipated the tensions between photographers and editors that continue to shape the field. And his willingness to sacrifice his health, his finances, and his personal relationships in pursuit of what he believed to be right made him not only one of the greatest photographers of the twentieth century but one of its most compelling and tragic figures.