The modernist master who revealed the extraordinary within the ordinary, transforming peppers, shells, sand dunes, and the human body into images of such formal perfection that they redefined what a photograph could be and what it meant to see clearly.

1886, Highland Park, Illinois – 1958, Carmel, California — American

Edward Henry Weston was born in 1886 in Highland Park, Illinois, a comfortable suburb north of Chicago. His father gave him his first camera at the age of sixteen, and the young Weston took to photography with an immediate and consuming passion. He briefly attended the Illinois College of Photography before moving to California in 1906, where he would remain, apart from significant periods in Mexico, for the rest of his life. He settled first in Tropico (now Glendale), establishing a portrait studio that earned him a growing reputation for the soft-focus, romanticised style associated with Pictorialism — the dominant aesthetic of art photography in the early twentieth century.

For more than a decade, Weston produced accomplished Pictorialist work that won prizes and recognition. But by the early 1920s, he had grown restless with the soft-focus aesthetic, recognising in its deliberate blur and atmospheric effects a dishonesty that masked the camera's true nature. The encounter with modernism — through the abstract photographs of Paul Strand, the paintings of the European avant-garde, and the intellectual ferment of the post-war era — precipitated a crisis of vision that would resolve itself into the most radical transformation in the history of American photography.

In 1923, Weston sailed to Mexico with the Italian-born photographer Tina Modotti, his lover and artistic companion. The three years he spent in Mexico were a period of explosive creative growth. Freed from the commercial pressures of his portrait studio, stimulated by the vitality of Mexican culture and the company of artists including Diego Rivera, David Alfaro Siqueiros, and José Clemente Orozco, Weston abandoned Pictorialism entirely and embraced a new aesthetic of sharp focus, precise exposure, and absolute fidelity to the subject before the lens. His photographs of Mexican folk toys, cloud formations, and the industrial forms of factories and grain elevators announced a visual language of unprecedented clarity and formal rigour.

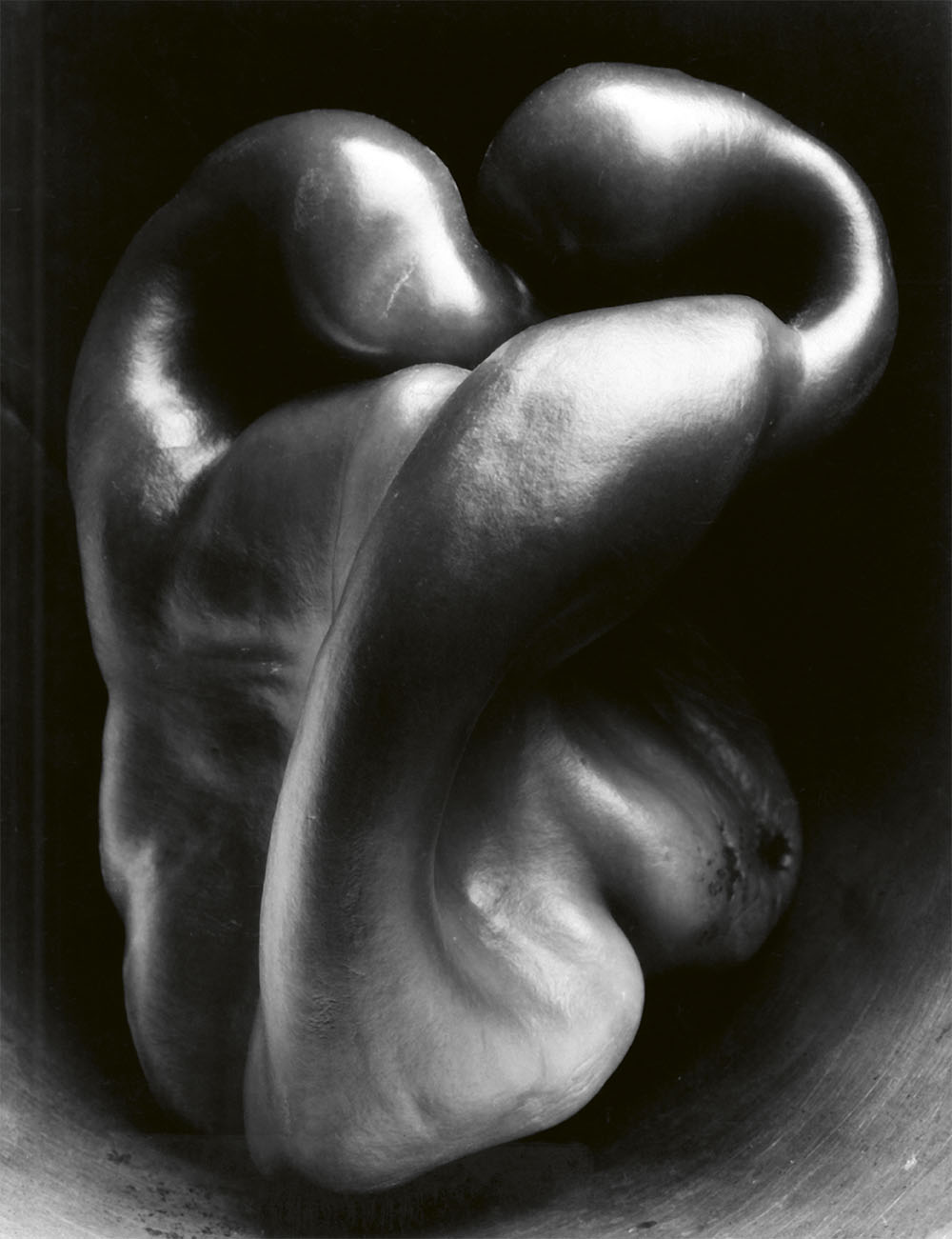

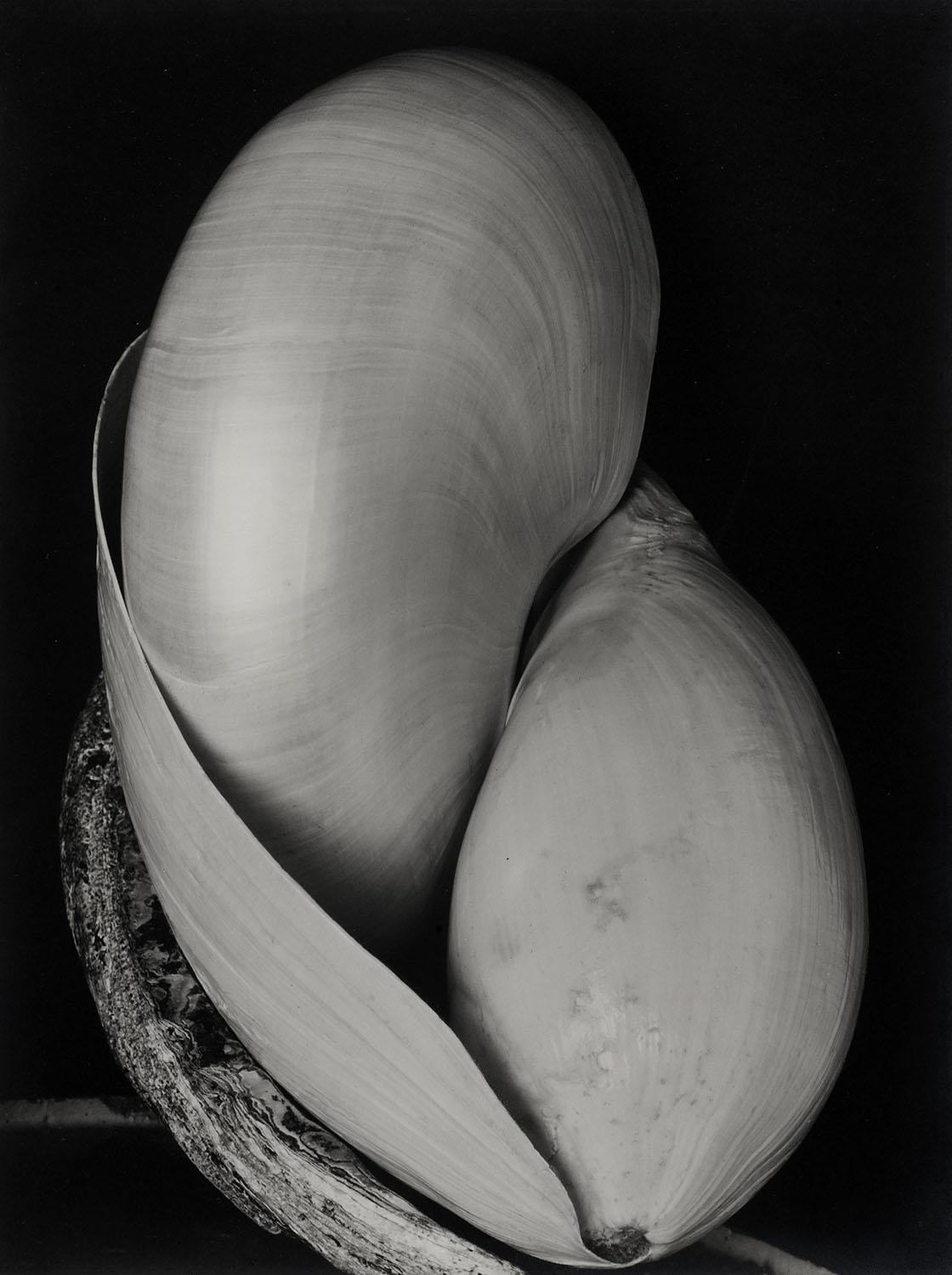

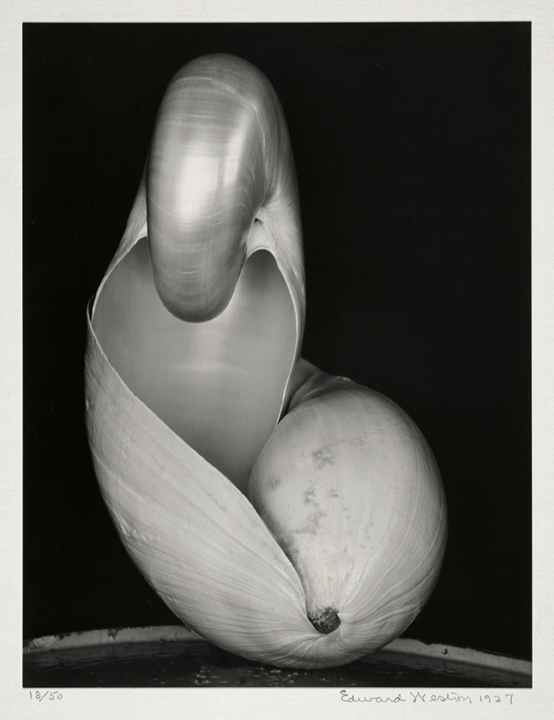

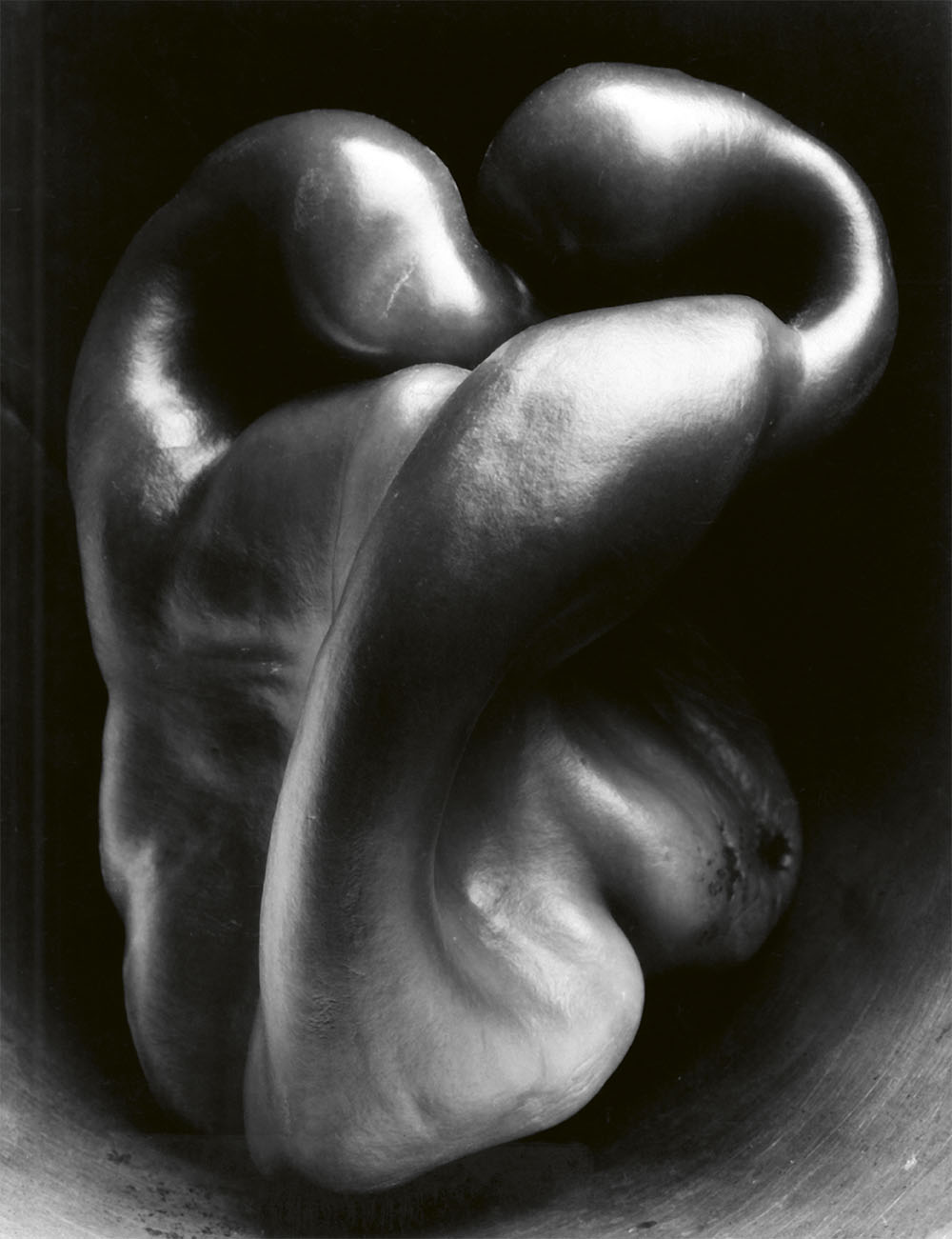

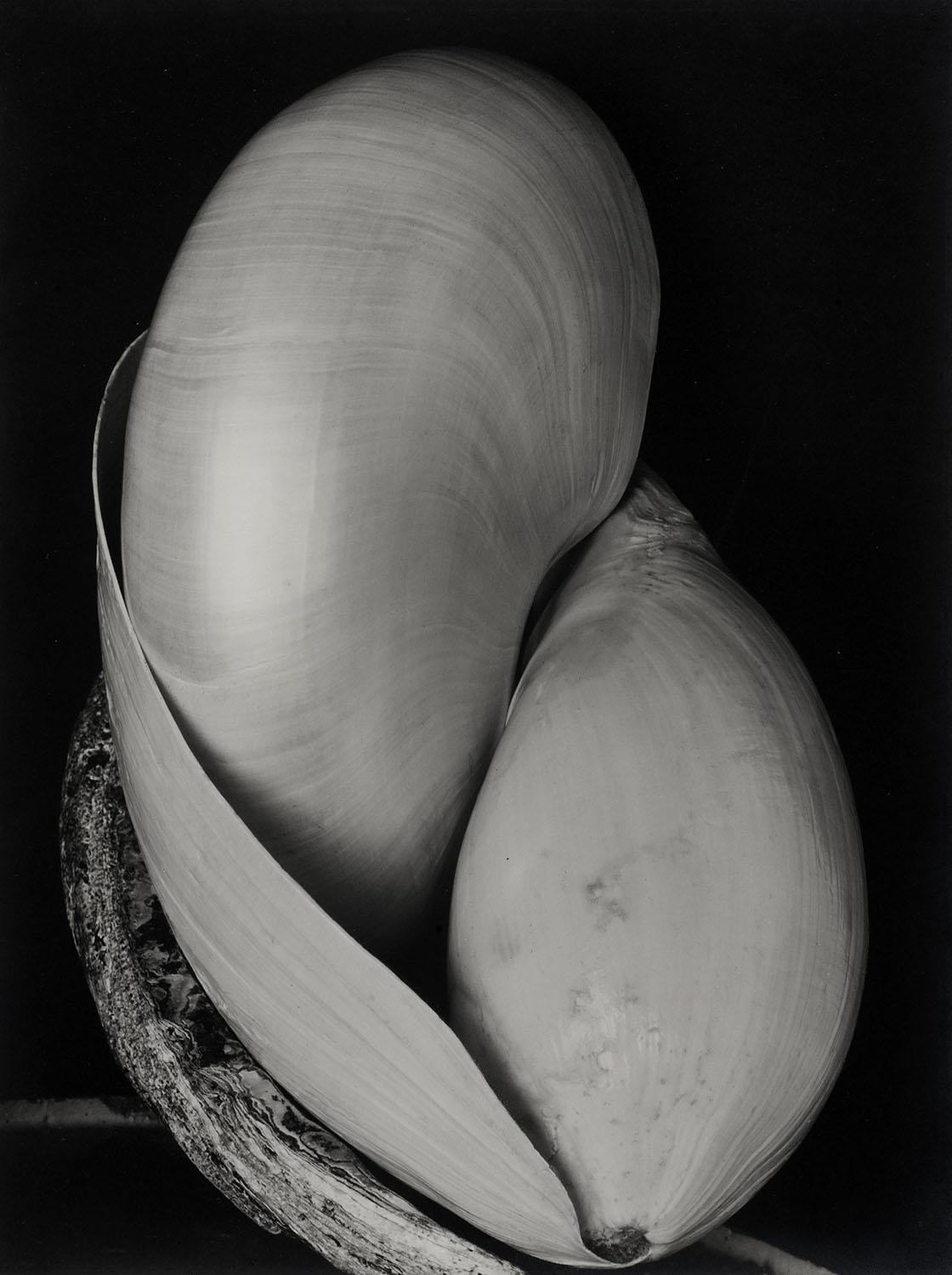

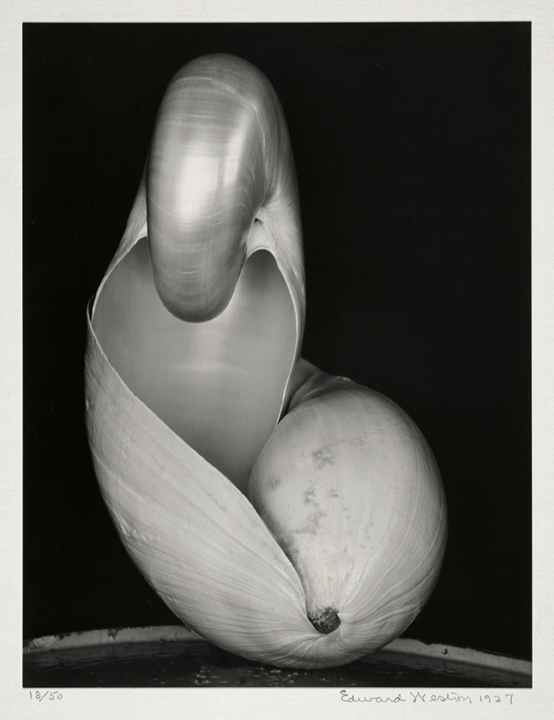

Returning to California in 1926, Weston entered the most productive decade of his career. Working with a large-format 8x10 view camera, using natural light, and printing by contact without enlargement, he produced a body of close-up studies of natural forms — peppers, shells, mushrooms, artichokes, cabbage leaves — that rank among the supreme achievements of photographic modernism. The most famous of these, Pepper No. 30 (1930), depicts a single green pepper photographed inside a tin funnel, its sinuous curves and deep shadows creating an image that simultaneously suggests a human torso, a piece of sculpture, and a natural form of breathtaking organic beauty. Weston photographed the pepper over a period of days, making dozens of exposures before arriving at the image he considered definitive.

What Weston sought in these close-up studies was not symbolism or metaphor but what he called the thing itself — the essential reality of the object as revealed through the camera's unique capacity for precise description. He believed that photography's strength lay not in imitating other art forms but in exploiting its own distinctive qualities: sharp focus, fine tonal gradation, and the ability to render surface texture and material substance with a fidelity no other medium could match. This philosophy of straight photography — unmanipulated, sharply focused, and committed to the integrity of the photographic print — became the foundation of American photographic modernism.

In 1932, Weston joined with Ansel Adams, Willard Van Dyke, Imogen Cunningham, and several other California photographers to form Group f/64, named after the smallest aperture setting on a large-format camera lens, which produces the greatest depth of field and sharpness. The group's manifesto declared their commitment to pure, unmanipulated photography and their opposition to the Pictorialist aesthetic of soft focus and handwork. Though the group was short-lived, its principles defined the direction of West Coast photography for the rest of the century.

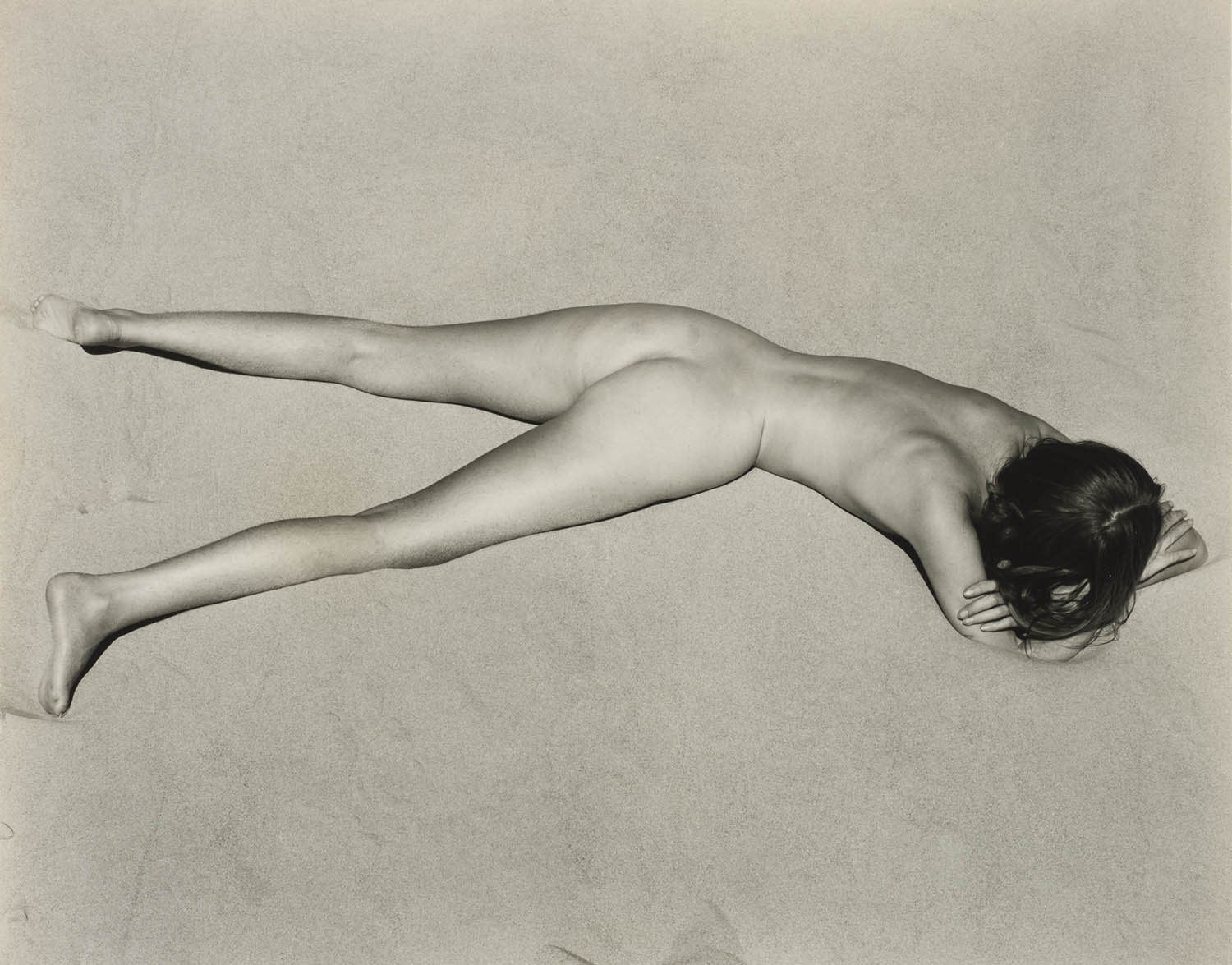

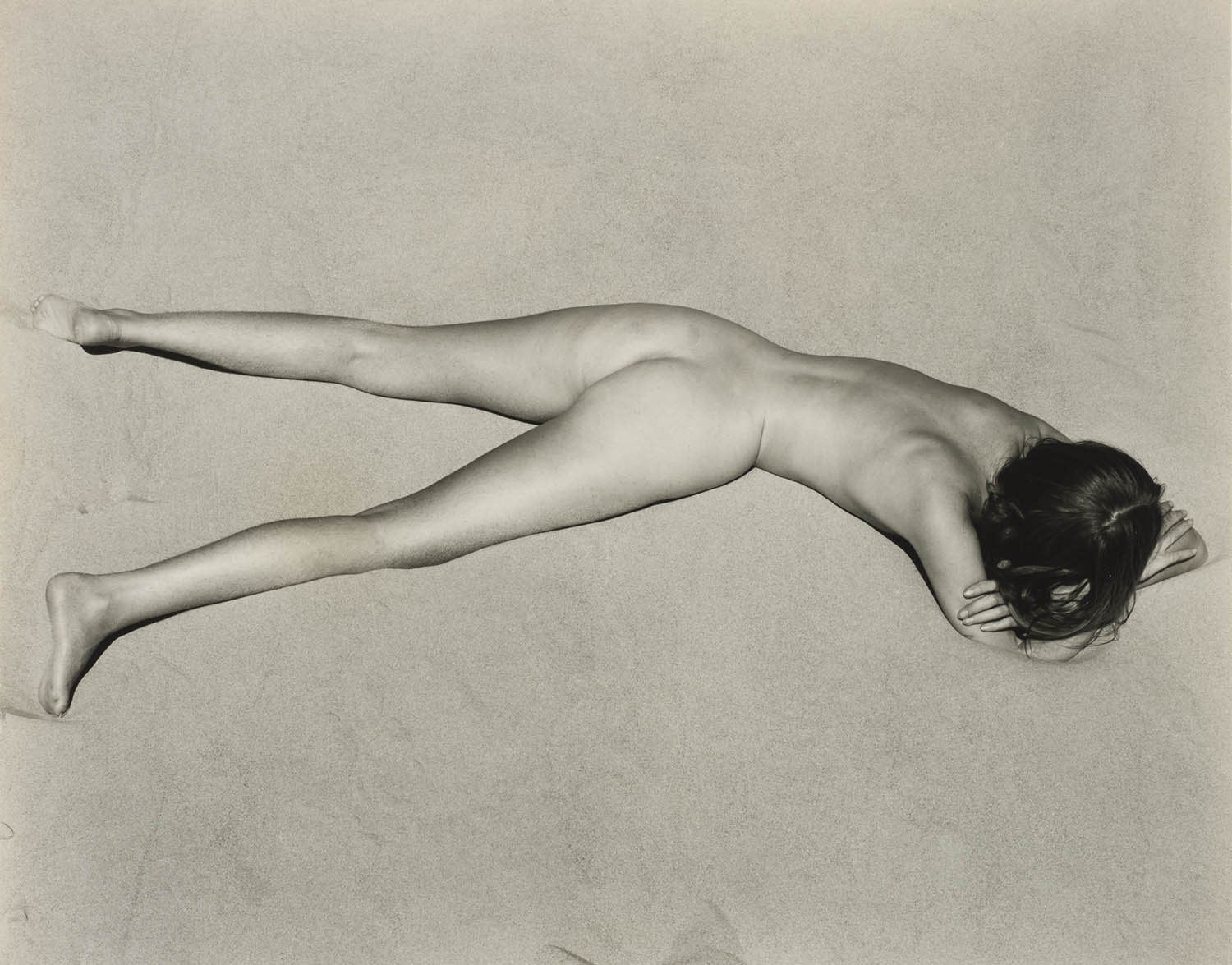

In 1937, Weston became the first photographer to receive a Guggenheim Fellowship, which funded two years of travel and photography throughout California and the American West. The resulting images — landscapes of the Mojave Desert, the sand dunes at Oceano, the eroded rocks and twisted cypress trees of Point Lobos near his home in Carmel — extended his modernist vision to the grandeur of the natural landscape while maintaining the same intensity of seeing he brought to a single pepper or shell.

By the mid-1940s, Weston began to show symptoms of Parkinson's disease, and he made his last photographs at Point Lobos in 1948. He spent his final decade overseeing the printing of a definitive collection of his life's work, assisted by his sons Brett and Cole Weston, both accomplished photographers in their own right. He died in Carmel in 1958, leaving behind a body of work that permanently established photography as a medium of artistic vision equal to painting and sculpture, and a philosophy of seeing that continues to inform photographic practice to this day.

To consult the rules of composition before making a picture is a little like consulting the law of gravity before going for a walk. Edward Weston

The most celebrated photograph of a natural form ever made, depicting a single green pepper whose sinuous curves and deep shadows transcend their subject to become an image of universal formal beauty and sensuous power.

A series of luminous photographs of the sand dunes at Oceano, California, in which the interplay of light and shadow transforms geological formations into abstract compositions of extraordinary purity and grace.

Weston's final great body of work, photographing the eroded rocks, tide pools, kelp, and twisted cypress trees near his home in Carmel with the same intensity of vision he brought to his close-up studies of natural forms.

Born in Highland Park, Illinois. Receives his first camera at the age of sixteen.

Opens a portrait studio in Tropico (now Glendale), California, producing Pictorialist work that wins national recognition.

Travels to Mexico with Tina Modotti, beginning a three-year period of radical artistic transformation.

Begins his celebrated series of close-up studies of shells, peppers, and other natural forms in his Carmel studio.

Creates Pepper No. 30, the photograph that will become the most iconic image of photographic modernism.

Co-founds Group f/64 with Ansel Adams, Imogen Cunningham, and others, codifying the principles of straight photography.

Becomes the first photographer to receive a Guggenheim Fellowship, funding two years of travel across the American West.

Makes his last photographs at Point Lobos, as Parkinson's disease increasingly limits his ability to work.

Dies in Carmel, California. His legacy as the founder of American photographic modernism is firmly established.

Interested in discussing photography, collaboration, or just want to say hello? I’d love to hear from you.

Contact →