The restless pioneer who proved a galloping horse lifts all four hooves from the ground, whose sequential motion studies dissolved the boundary between photography and cinema and forever changed how humanity perceives movement, time, and the mechanics of the living body.

1830, Kingston upon Thames, England – 1904, Kingston upon Thames, England — British-American

Eadweard Muybridge was born Edward James Muggeridge in 1830 in Kingston upon Thames, England, a market town on the outskirts of London. He emigrated to the United States as a young man, arriving in San Francisco around 1855, where he worked initially as a bookseller and publisher's agent. The circumstances of his transformation from a provincial English tradesman into one of the most consequential figures in the history of photography remain partly mysterious, but by the mid-1860s he had reinvented himself — adopting the archaic Saxon spelling of his name — and taken up the camera with an ambition that would reshape the boundaries of the medium.

His early photographic work in California established him as one of the foremost landscape photographers of the American West. Between 1867 and 1873, Muybridge produced mammoth-plate views of Yosemite Valley, the Pacific coastline, and the rapidly expanding city of San Francisco that rivalled the work of Carleton Watkins in their grandeur and technical accomplishment. He photographed with enormous glass-plate negatives, hauling heavy equipment into remote terrain, and his images of Yosemite's granite cliffs and waterfalls displayed a dramatic sensibility that went beyond mere topographic record. He used cloud negatives composited with landscape plates, manipulated exposure times, and employed unusual vantage points to create images of theatrical power.

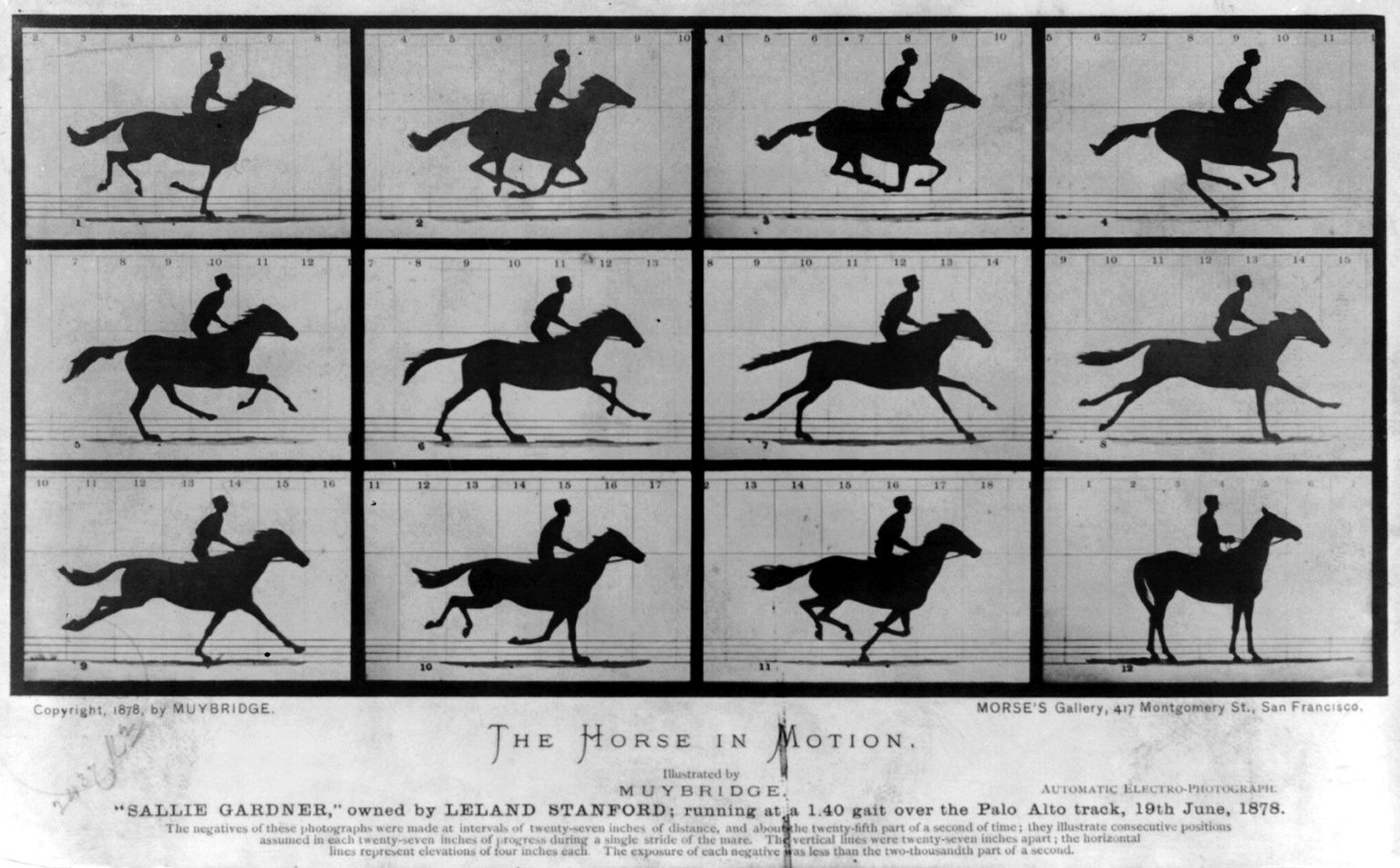

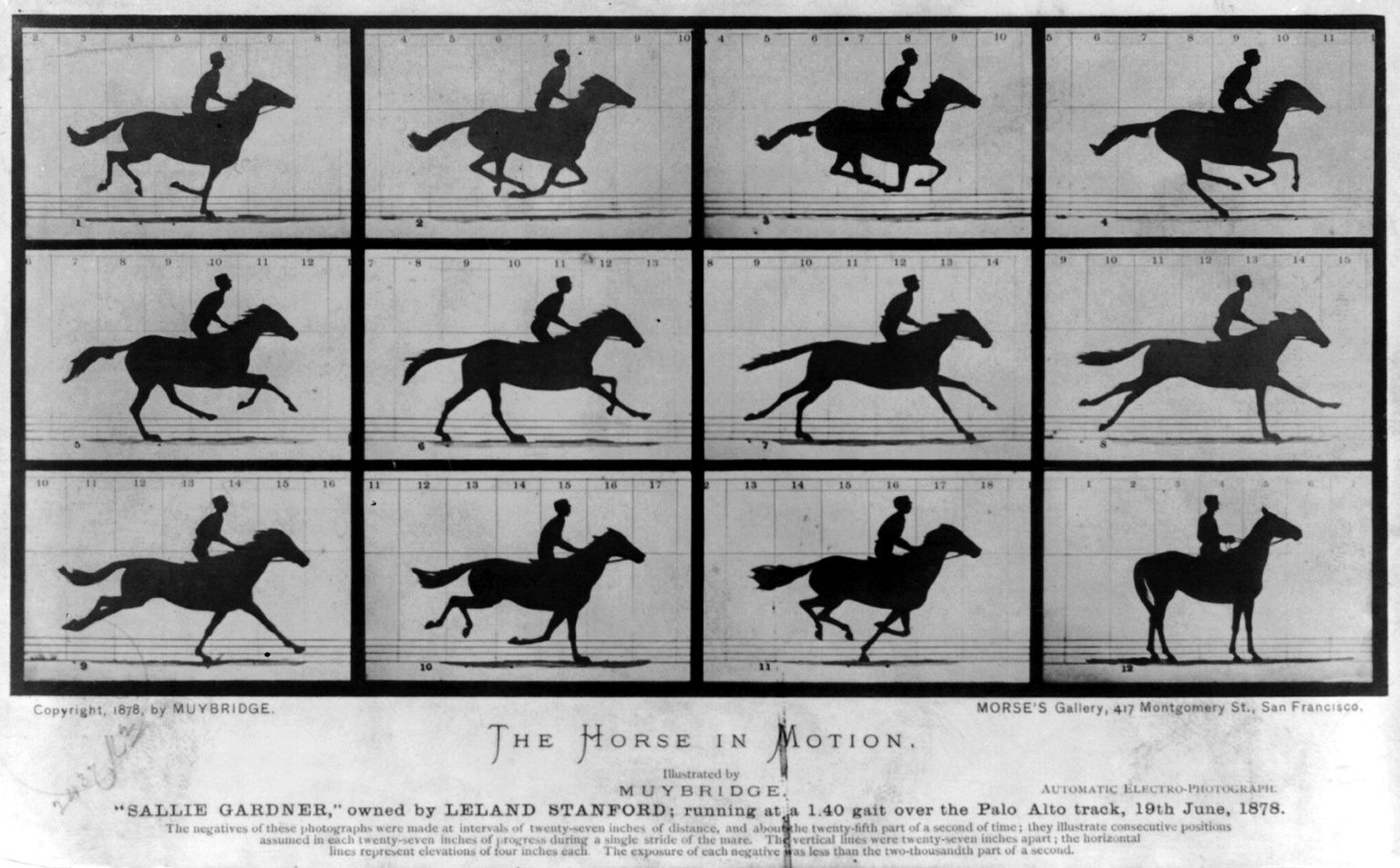

The event that would define Muybridge's legacy began in 1872, when Leland Stanford, the railroad magnate and former governor of California, hired him to settle a popular debate: whether all four hooves of a galloping horse left the ground simultaneously at any point in its stride. The question had fascinated artists and scientists for centuries, but the speed of a horse's gait made it impossible to resolve with the naked eye. Muybridge's initial attempts at Palo Alto in 1873 were inconclusive, but after years of refinement he returned in 1878 with an elaborate system of twelve cameras fitted with electromagnetic shutters, triggered by threads stretched across a specially constructed track. The resulting sequence of photographs — showing Stanford's horse Sallie Gardner in full gallop — provided irrefutable proof that a horse does indeed become fully airborne during its stride.

The photographs caused a sensation that reverberated far beyond the world of horse racing. Artists discovered that centuries of equestrian painting had been wrong: the conventional rocking-horse posture, with front and back legs extended simultaneously, bore no resemblance to actual locomotion. Scientists recognised that photography could reveal truths invisible to unaided perception. And Muybridge himself glimpsed a possibility that would consume the remainder of his career: if sequential photographs could decompose movement into its constituent phases, perhaps they could also be reassembled to recreate the illusion of motion.

In 1879, Muybridge invented the zoopraxiscope, a device that projected painted images derived from his photographs onto a screen in rapid succession, producing what many historians regard as the first moving pictures. He demonstrated the zoopraxiscope to audiences across Europe and America, including a celebrated presentation at the Royal Institution in London in 1882, electrifying viewers who had never seen images appear to move. The device was a crucial stepping stone on the path from still photography to cinema, anticipating by more than a decade the work of Thomas Edison and the Lumière brothers.

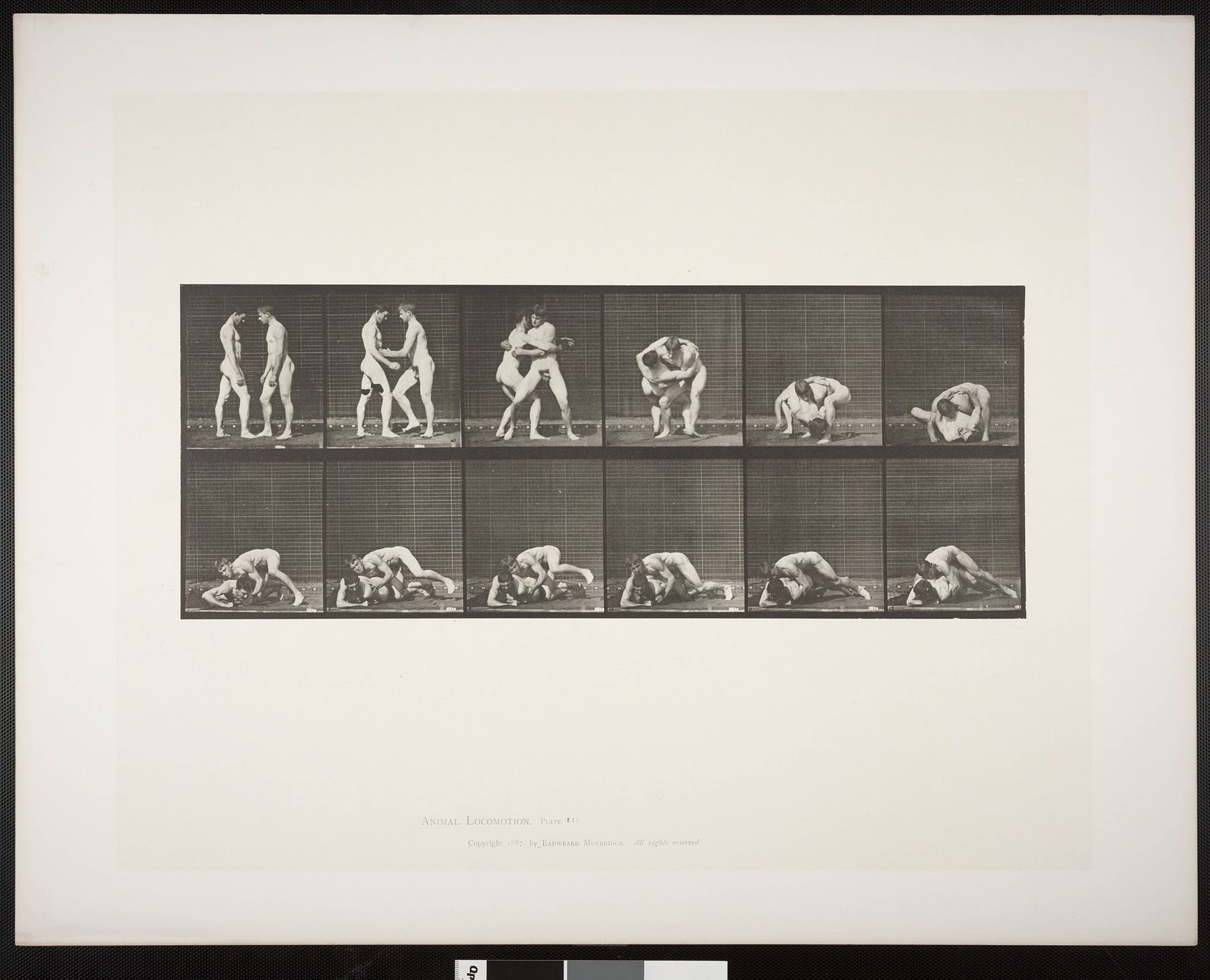

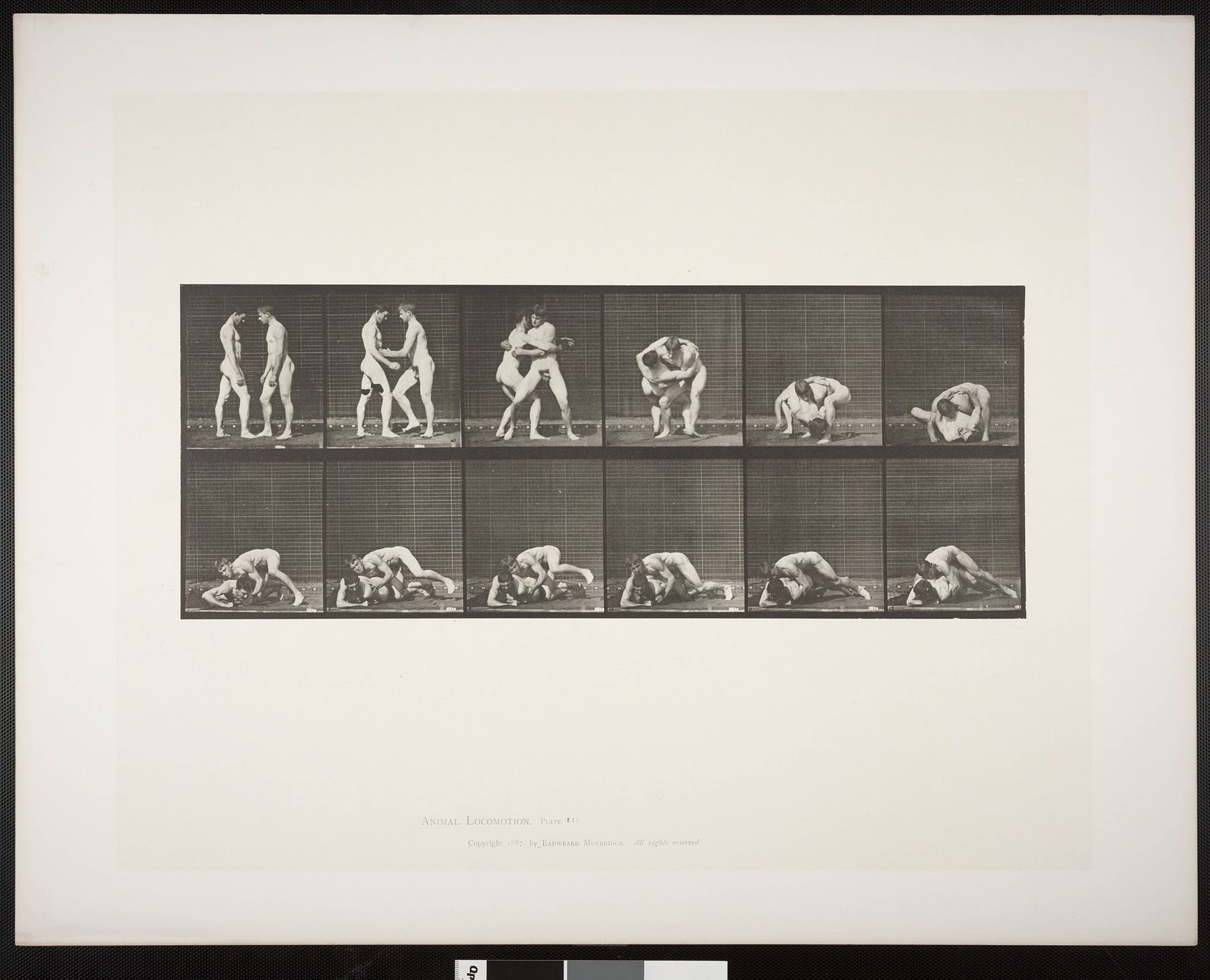

From 1884 to 1886, Muybridge conducted his most ambitious project at the University of Pennsylvania, producing the monumental Animal Locomotion, a collection of 781 collotype plates documenting the movement of humans, animals, and birds. The subjects included men, women, and children engaged in every conceivable activity — walking, running, jumping, climbing stairs, throwing objects, wrestling, dancing — as well as horses, dogs, cats, deer, eagles, and other creatures. Many of the human subjects were photographed nude, and the resulting plates possess an unexpected beauty that transcends their scientific purpose, combining the rigour of anatomical study with the formal elegance of classical figure composition.

Muybridge's personal life was as turbulent as his professional achievements were methodical. In 1874, he discovered that his wife Flora's infant son may have been fathered by a drama critic named Harry Larkyns. Muybridge tracked Larkyns to a ranch in Napa Valley and shot him dead. At his subsequent murder trial, Muybridge was acquitted on the grounds of justifiable homicide, and he promptly departed for an extended photographic expedition to Central America. The episode reveals something of the volatile temperament that coexisted with the patient, systematic mind capable of designing the most sophisticated photographic apparatus of the age.

He returned to England in 1894 and spent his final decade in his birthplace of Kingston upon Thames, where he died in 1904. His influence extends across art, science, and technology. Francis Bacon drew directly on the Animal Locomotion plates for his contorted figure paintings. Filmmakers, animators, and digital artists continue to engage with the sequential logic he pioneered. His work stands at the intersection of art and science, beauty and evidence, the visible and the revealed, and his fundamental insight — that the camera can show us what the eye cannot see — remains one of the most transformative ideas in the history of visual culture.

Only photography has been able to divide human life into a series of moments, each of them has the value of a complete existence. Eadweard Muybridge

The landmark sequence of photographs proving that all four hooves of a galloping horse leave the ground simultaneously, commissioned by Leland Stanford and produced at the Palo Alto Stock Farm using twelve cameras with electromagnetic shutters.

A monumental portfolio of 781 collotype plates produced at the University of Pennsylvania, documenting the sequential movement of humans, animals, and birds in unprecedented scientific and aesthetic detail.

Large-format landscape photographs of Yosemite's granite cliffs, waterfalls, and forests that established Muybridge as one of the preeminent photographers of the American West alongside Carleton Watkins.

Born Edward James Muggeridge in Kingston upon Thames, England.

Emigrates to the United States and settles in San Francisco, initially working as a bookseller.

Begins producing mammoth-plate landscape photographs of Yosemite Valley and the American West.

Leland Stanford commissions Muybridge to photograph a horse in motion, beginning the experiments that will define his legacy.

Produces the definitive Horse in Motion sequence at Palo Alto, proving that a galloping horse becomes fully airborne.

Invents the zoopraxiscope, projecting sequential images to create the illusion of motion — a precursor to cinema.

Conducts extensive motion studies at the University of Pennsylvania, producing the 781 plates of Animal Locomotion.

Lectures and demonstrates the zoopraxiscope at the World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago.

Returns to England, retiring to his birthplace of Kingston upon Thames.

Dies in Kingston upon Thames. His motion studies continue to influence art, science, animation, and cinema to this day.

Interested in discussing photography, collaboration, or just want to say hello? I’d love to hear from you.

Contact →