The poet of sequential photography, whose hand-written texts, staged narratives, and multi-frame sequences shattered the conventions of the single decisive moment, insisting that photography could tell stories, ask questions, and explore the invisible territories of dreams, desire, and mortality.

Born 1932, McKeesport, Pennsylvania — American

Duane Michals was born in 1932 in McKeesport, Pennsylvania, a steel town south of Pittsburgh whose industrial landscape and working-class culture shaped his early understanding of the world. His father worked in a steel mill, and the family lived modestly. Michals showed an early aptitude for drawing and visual thinking, but there was no tradition of art in the household, and the idea of becoming an artist seemed as remote as the galleries of New York. He attended the University of Denver on scholarship, graduating in 1953, and then served in the United States Army before moving to New York City, where he initially pursued a career in graphic design, working for Dance Magazine and Time magazine.

Photography entered his life almost by accident. In 1958, during a trip to the Soviet Union, Michals borrowed a camera and began photographing the people he encountered on the streets of Moscow and Leningrad. He had no formal training, no knowledge of darkroom technique, and no particular ambitions for the medium. What he discovered, however, was an instrument that could capture something he had long sensed but could not articulate: the fleeting, provisional nature of human experience, the way a moment dissolves even as it is being lived. The Russian portraits were direct, unaffected, and quietly intimate — qualities that would define his entire body of work.

Returning to New York, Michals built a successful career as a commercial photographer, shooting portraits and fashion for magazines including Vogue, Esquire, and Mademoiselle. But his personal work was moving in a direction that had no precedent in the medium. By the mid-1960s, he had begun creating photographic sequences — series of images arranged in narrative order that told stories, explored metaphysical ideas, and staged encounters with the invisible. These were not conventional photo essays or documentary series; they were closer to short films frozen on paper, or to the panel structures of comic strips reimagined for the gallery wall.

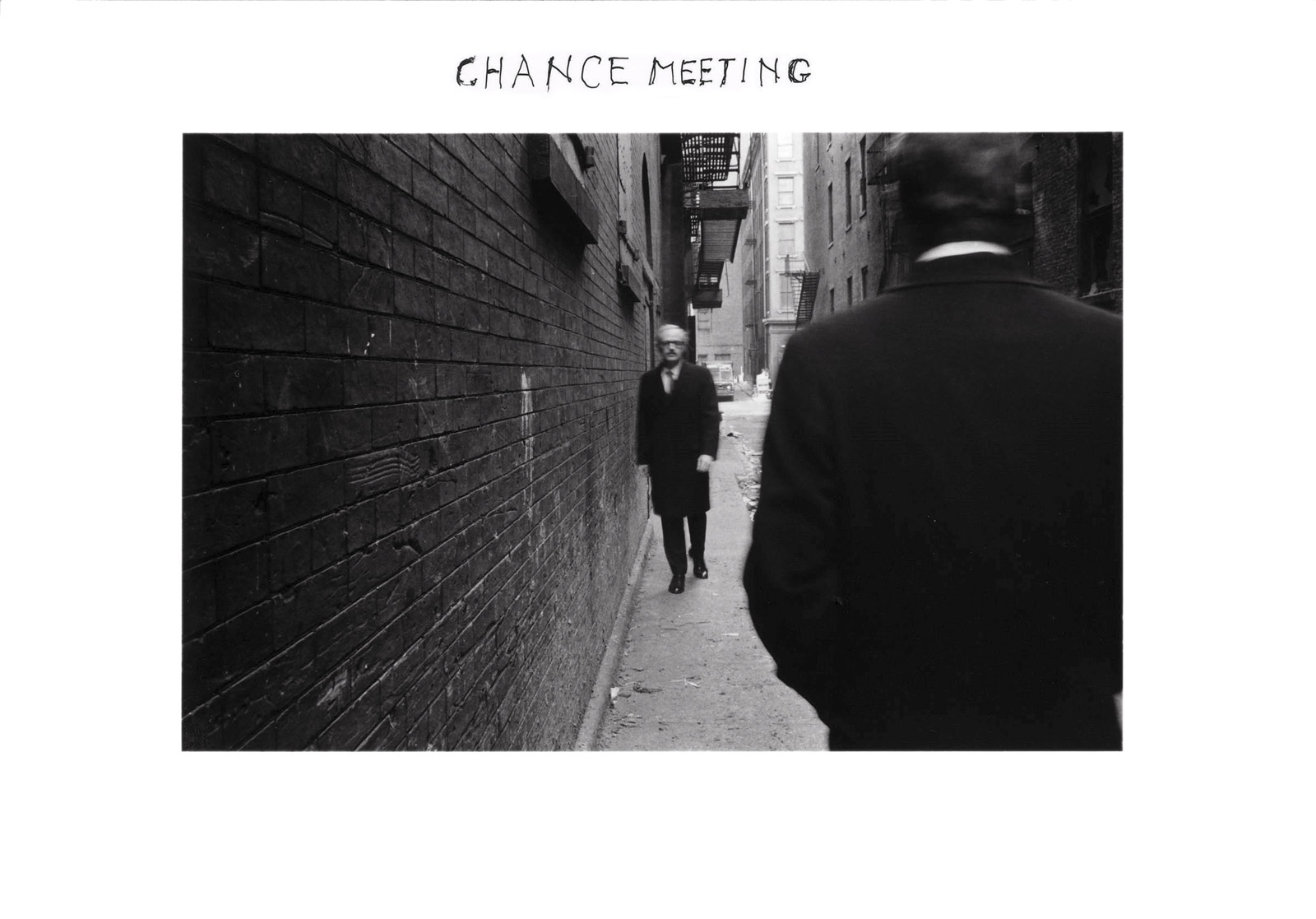

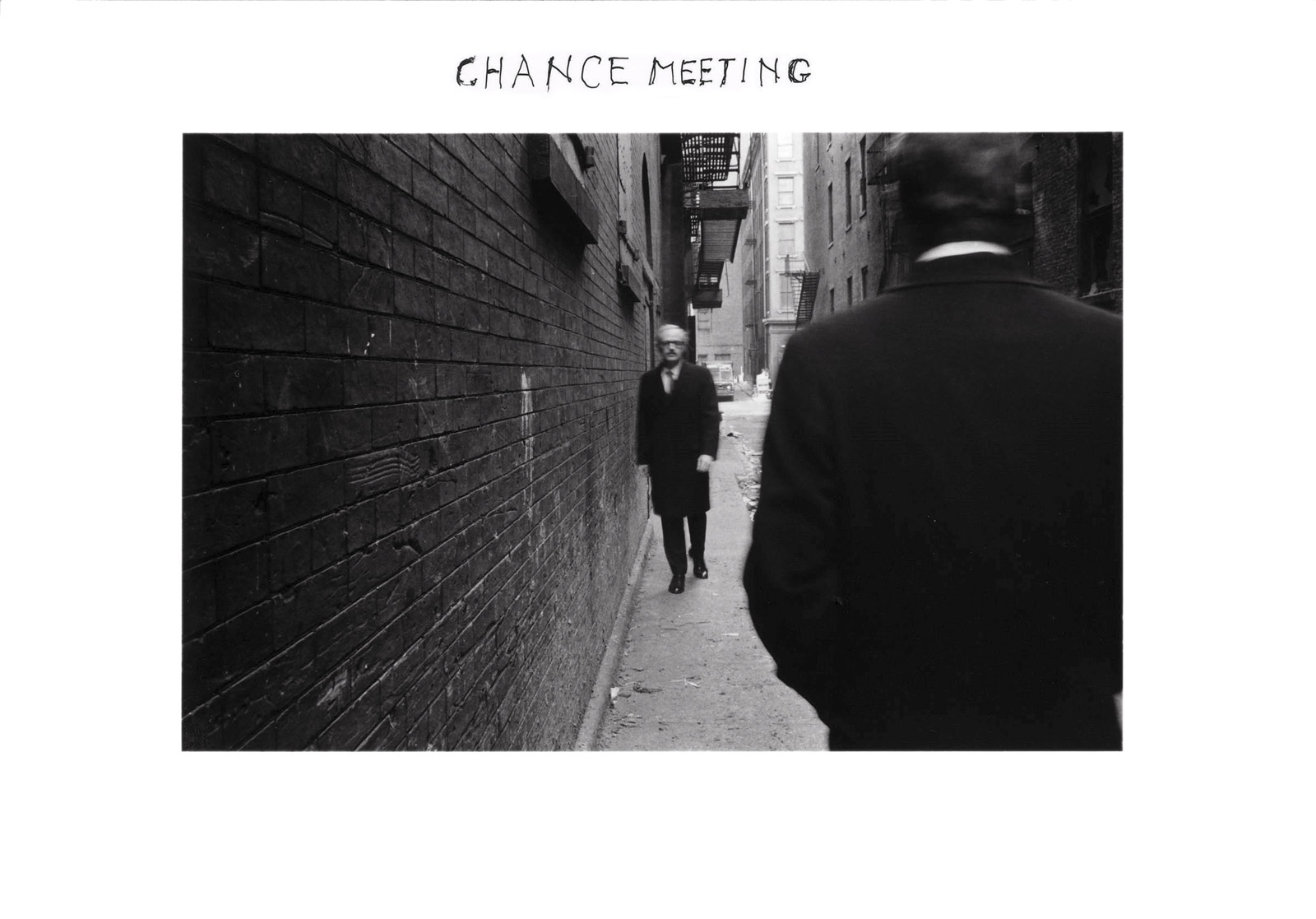

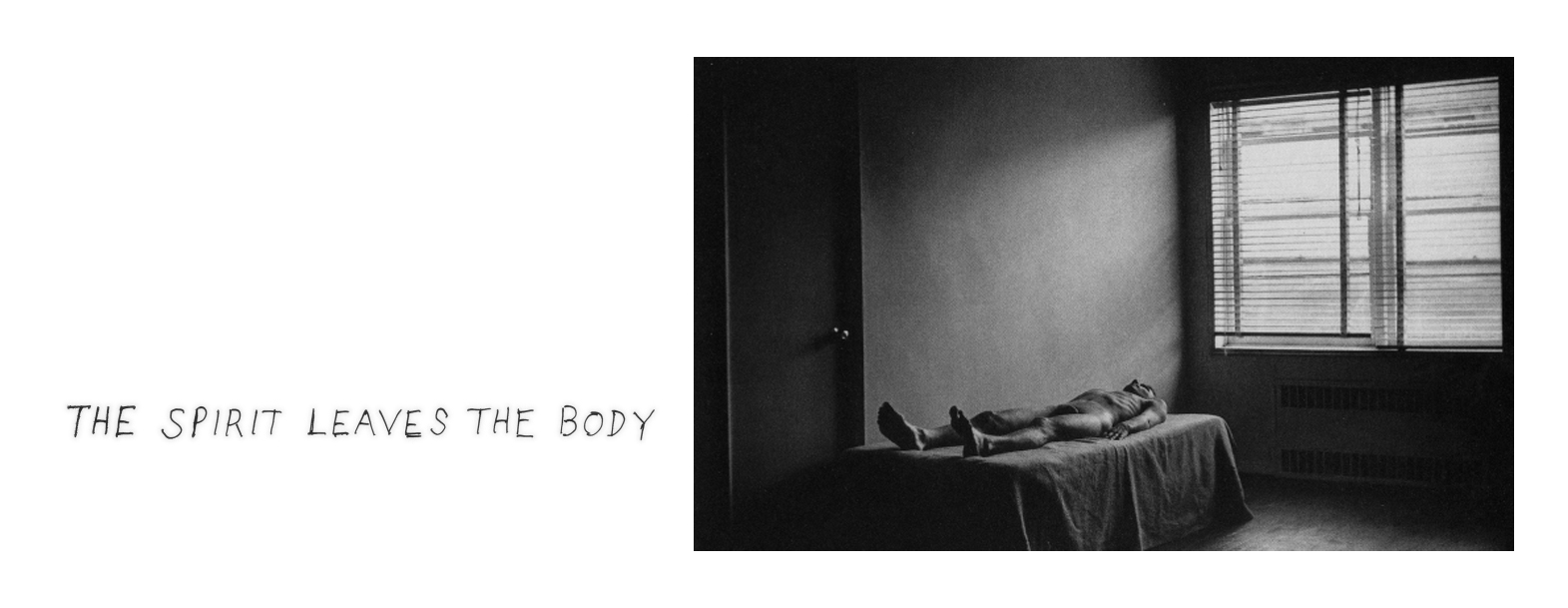

The sequences were revolutionary because they rejected the dominant orthodoxy of the single image. At a time when photographers from Henri Cartier-Bresson to Garry Winogrand prized the isolated, decisive moment, Michals insisted that a single photograph could never contain the fullness of experience. Time, he argued, was the essential dimension of human life, and photography needed to acknowledge its passage rather than pretending to arrest it. His sequences unfolded in time — five, six, sometimes nine frames that narrated an event from beginning to end, whether it was a spirit departing a body, two strangers passing on a street, or a man confronting his own mortality.

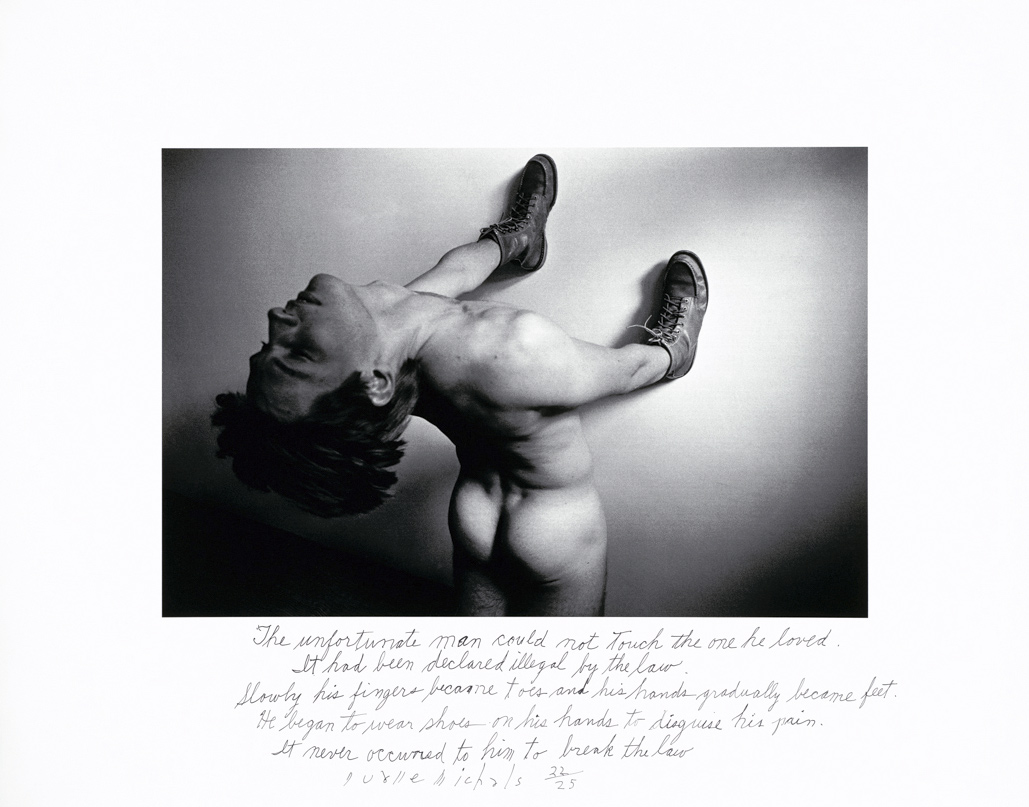

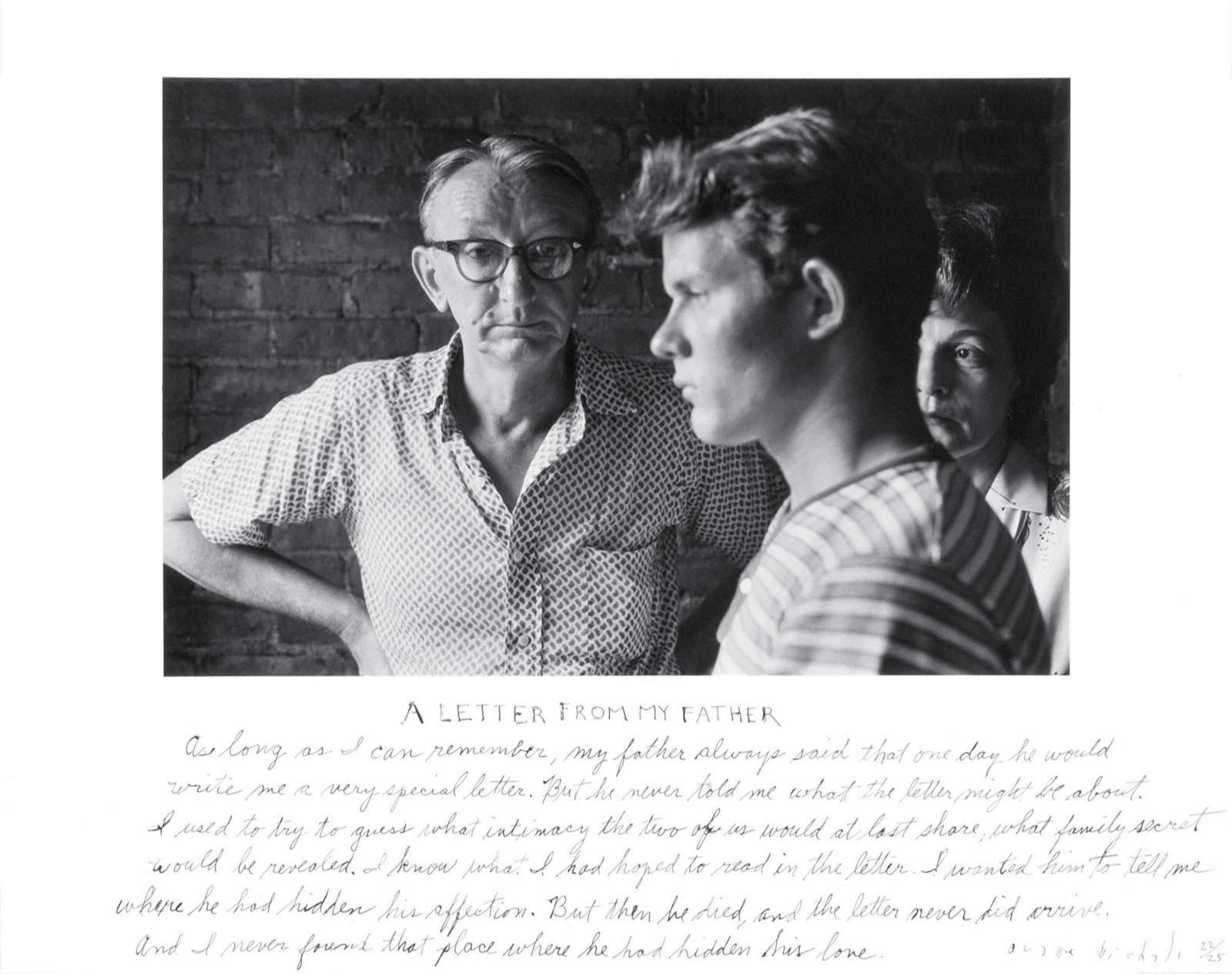

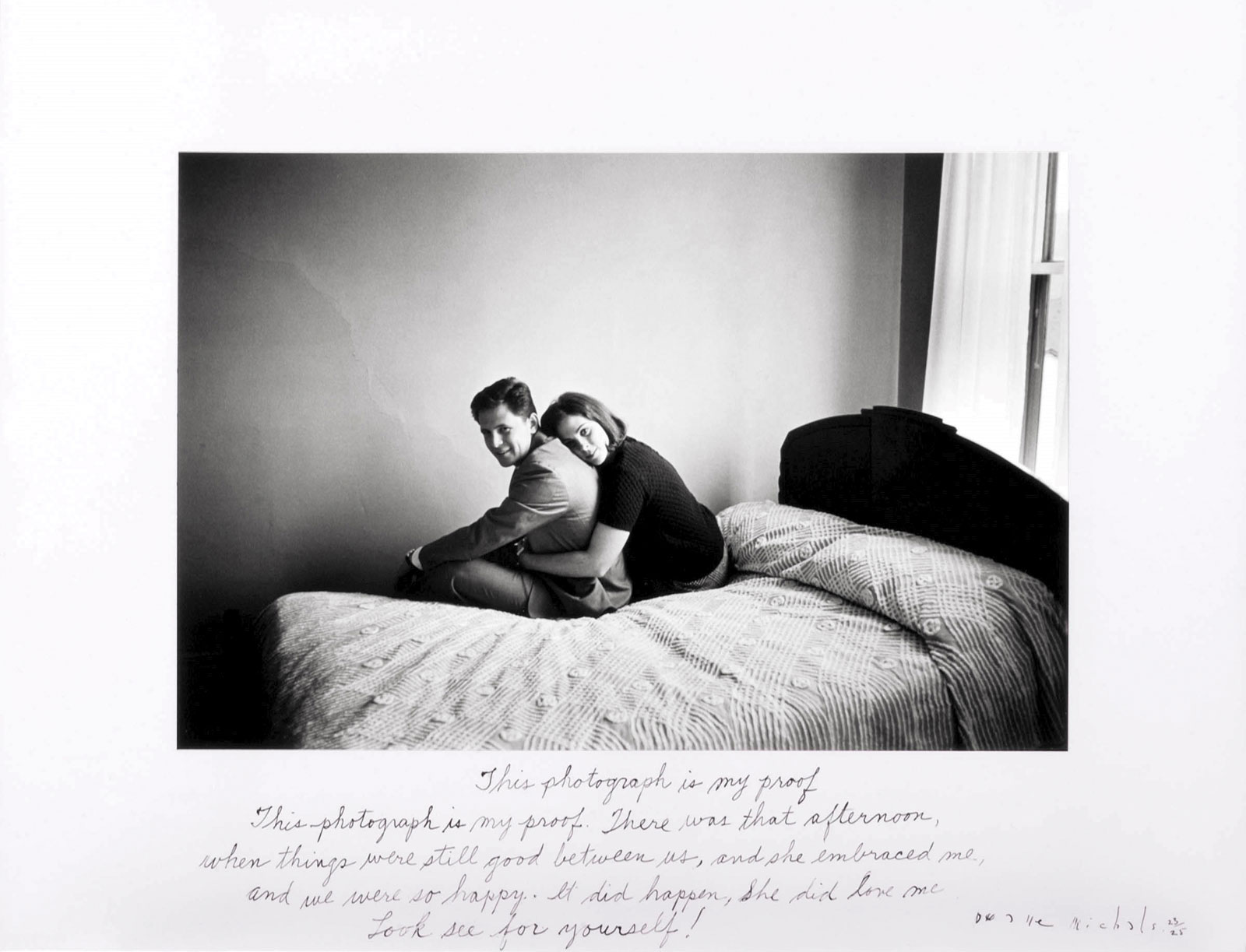

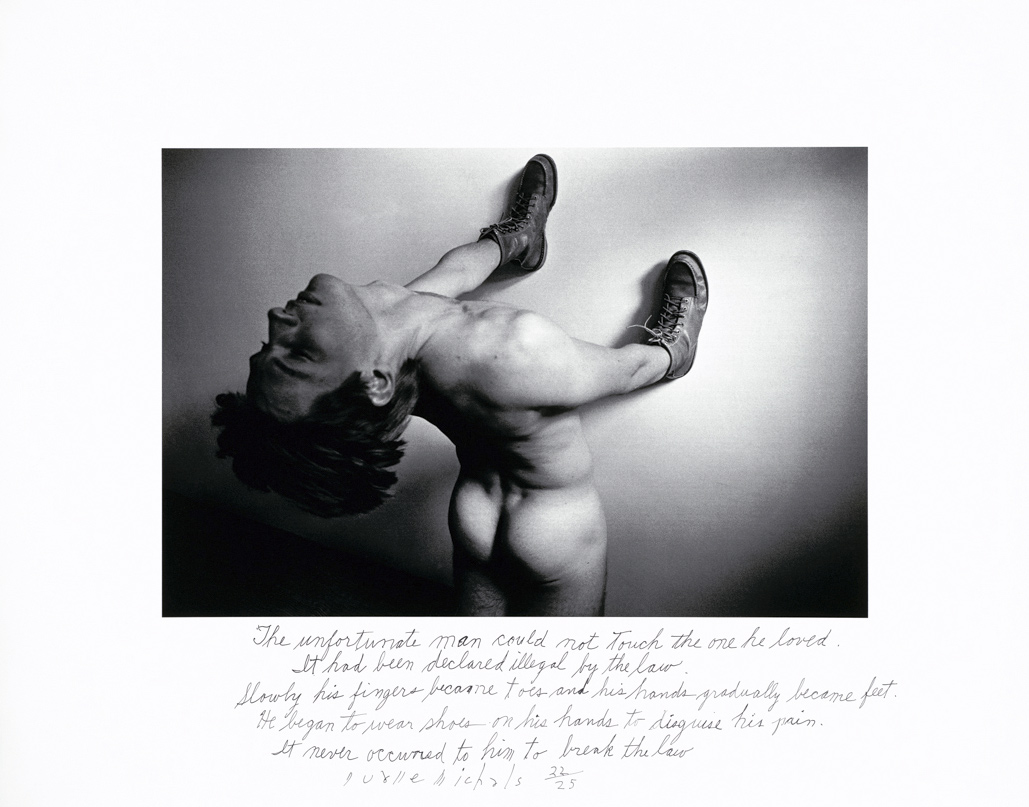

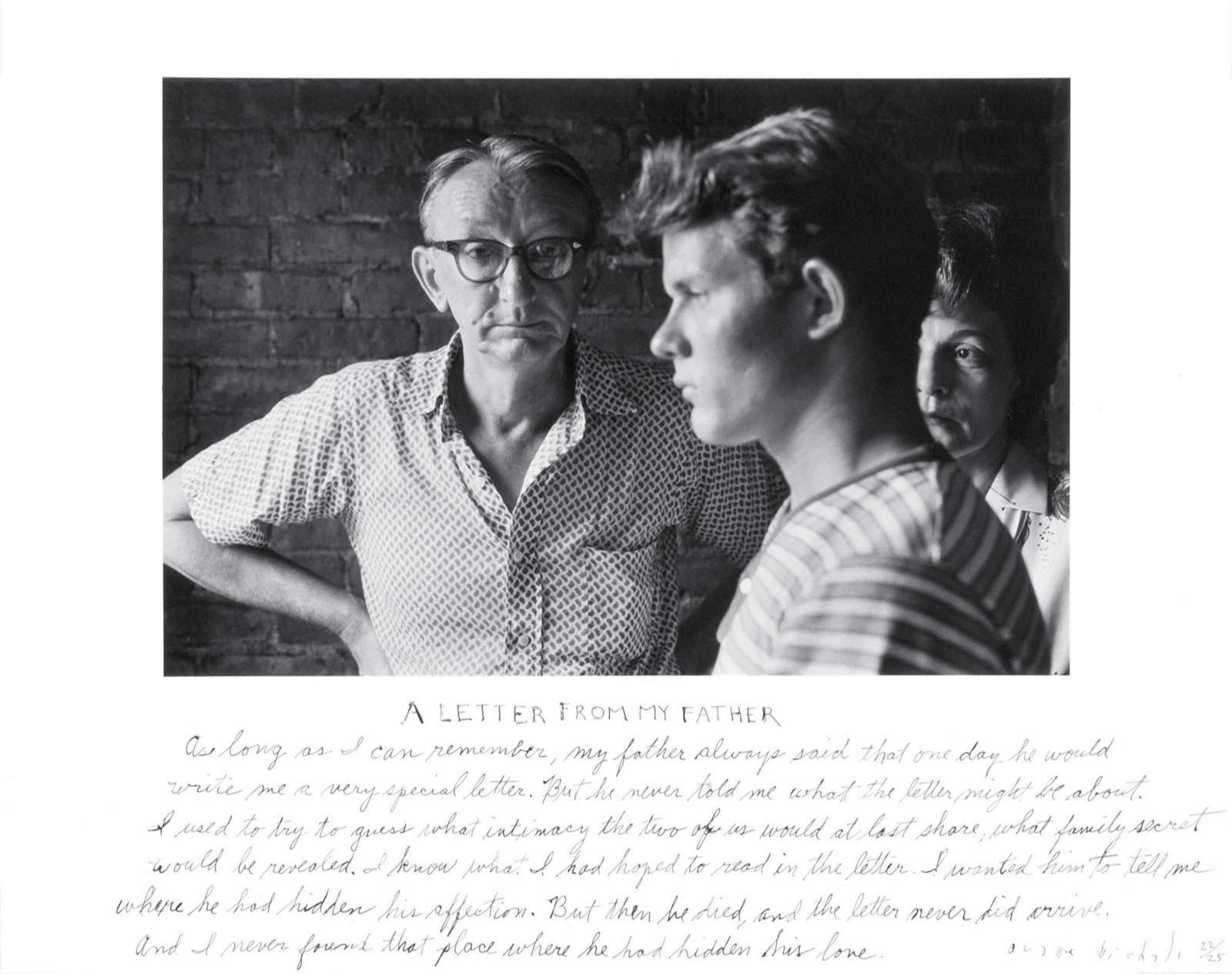

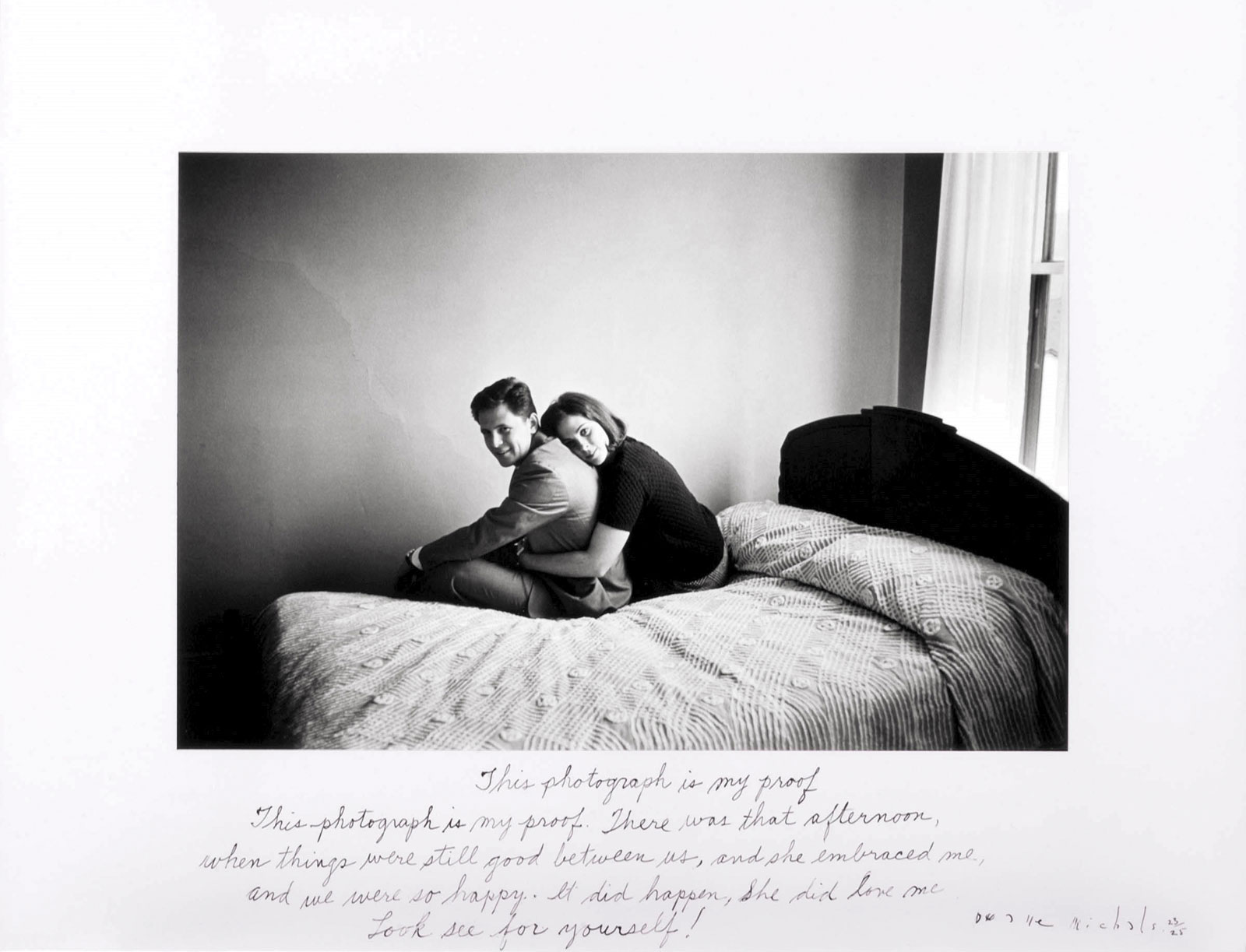

In the early 1970s, Michals introduced another radical innovation: handwritten text directly on his photographic prints. He wrote in a loose, personal script that ran across borders and beneath images, adding layers of meaning that the photographs alone could not convey. The texts were sometimes confessional, sometimes philosophical, sometimes wryly humorous. They spoke of love, loss, regret, desire, and the impossibility of fully knowing another person. This fusion of word and image anticipated by decades the mixed-media practices that would become commonplace in contemporary art photography.

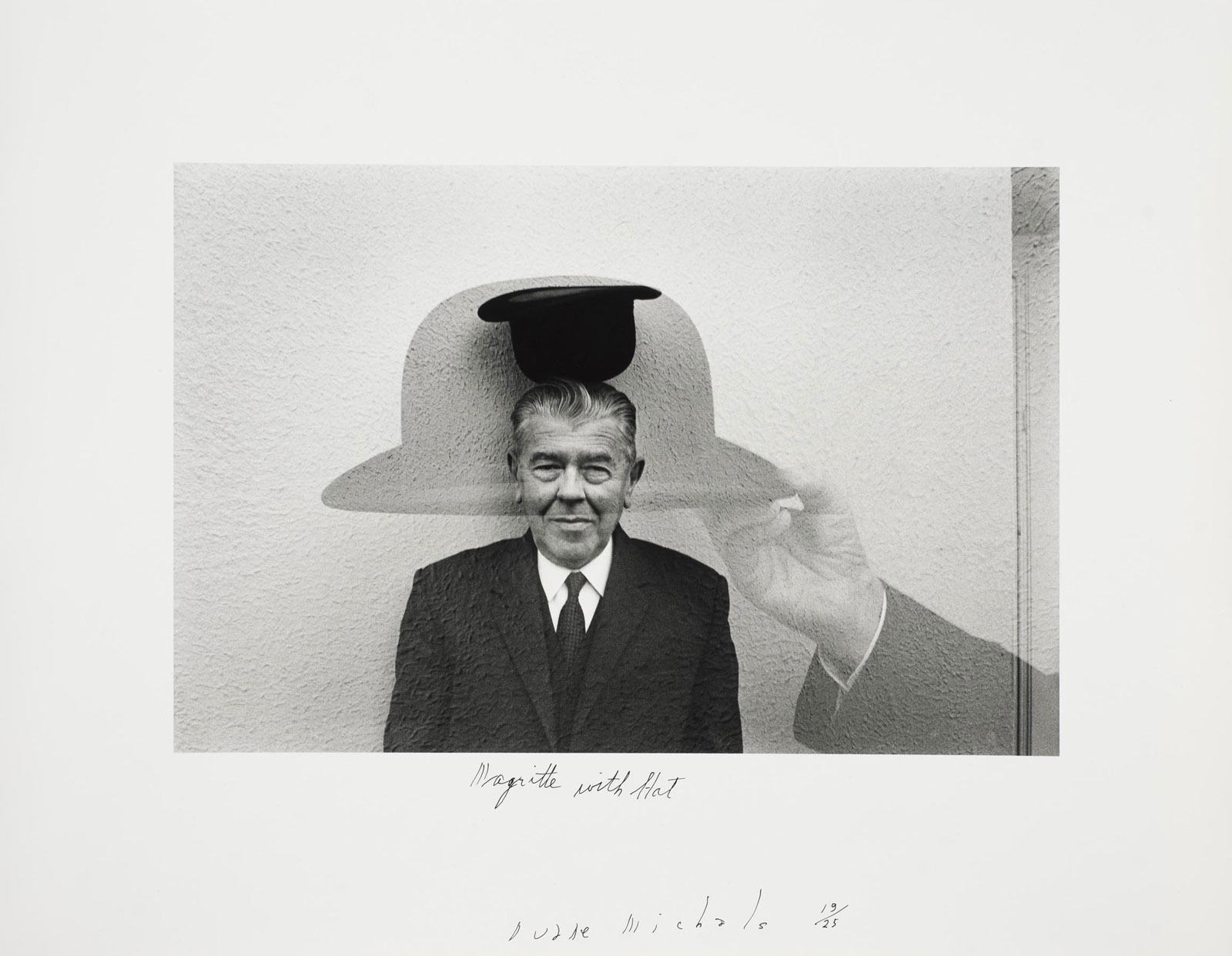

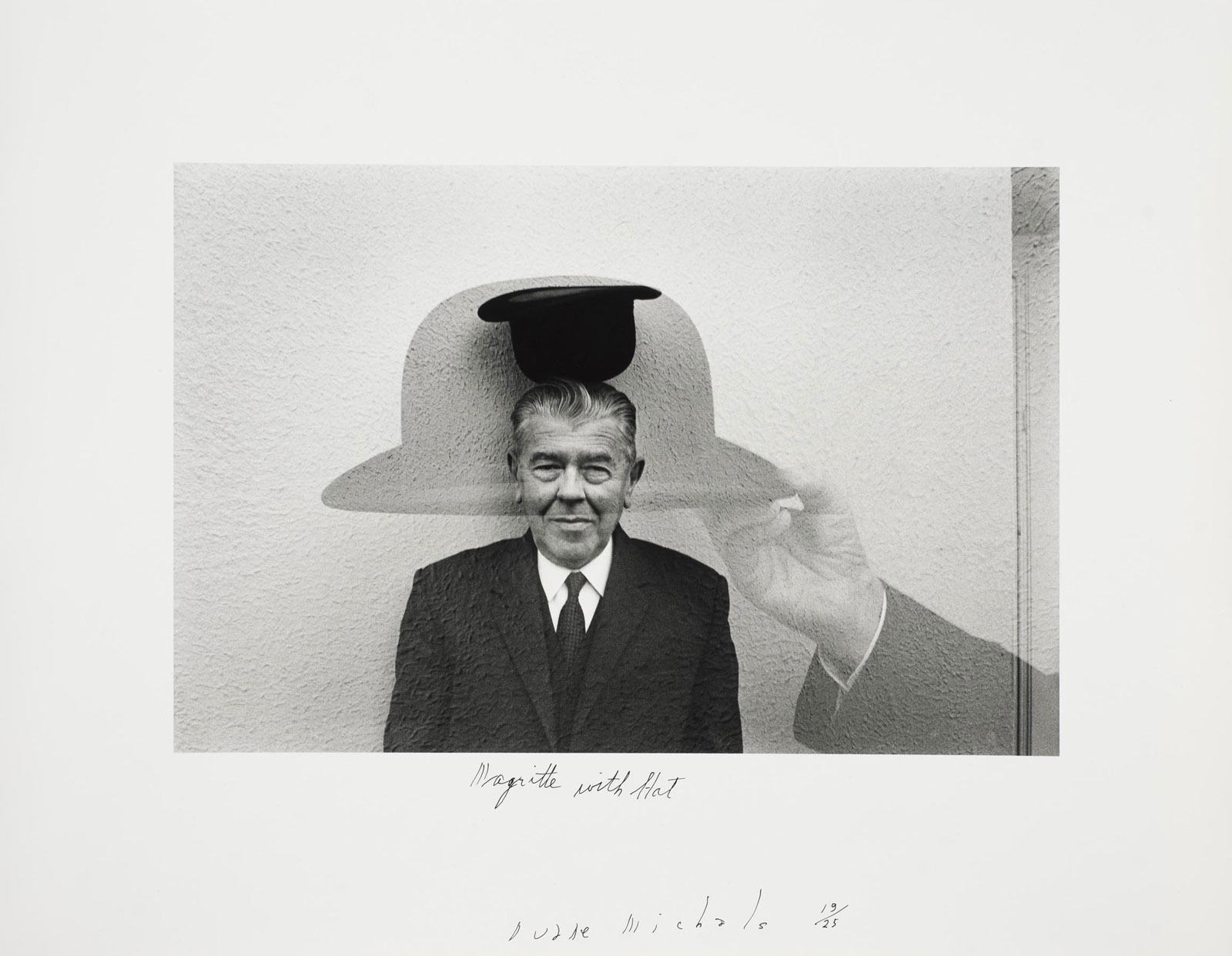

His portraits of artists and writers — René Magritte, Andy Warhol, Joseph Cornell, Marcel Duchamp — were unlike any portraits being made at the time. Rather than documenting the physical appearance of his subjects, Michals sought to evoke their inner worlds, their preoccupations, their creative spirits. The portrait of Magritte, taken in the Belgian painter's modest Brussels living room in 1965, became one of the most celebrated artist portraits of the twentieth century, capturing the quiet enigma of a man whose work had transformed the relationship between seeing and knowing.

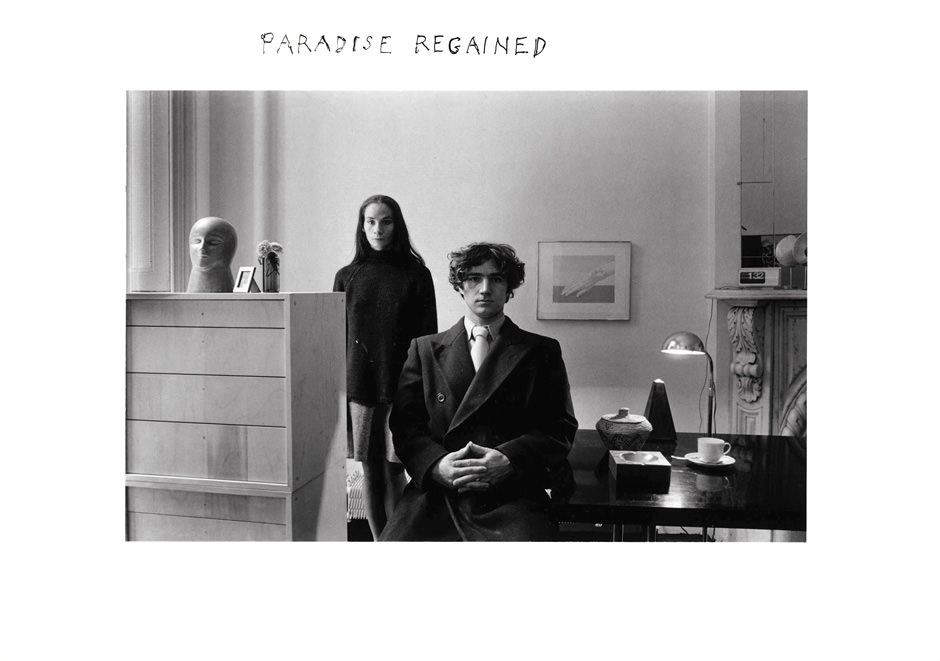

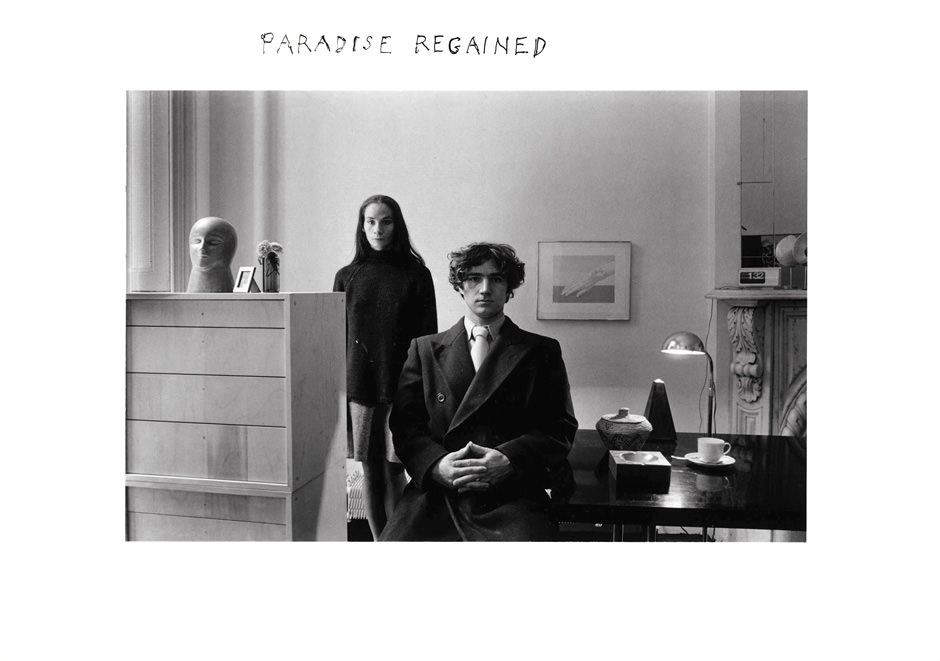

Throughout his career, Michals has drawn freely on the traditions of Surrealism, Symbolism, and Eastern philosophy, finding in these sources a language for the experiences that lie beyond the reach of the camera's mechanical eye. He has spoken often of his interest in what cannot be photographed — emotion, thought, memory, the passage of time, the presence of absence — and his work represents a sustained and deeply personal attempt to make the invisible visible. His influence extends across the boundaries of photography into performance art, conceptual art, and narrative installation.

Now in his nineties, Michals continues to work and exhibit with undiminished energy and inventiveness. His legacy is that of a photographer who refused to accept the limitations of his medium, who insisted that photography could be as subjective, as poetic, and as philosophically ambitious as painting or literature. In a field that has often privileged objectivity and formal rigour, Michals championed the personal, the emotional, and the metaphysical, opening doors through which countless subsequent artists have walked.

I believe in the imagination. What I cannot see is infinitely more important than what I can see. Duane Michals

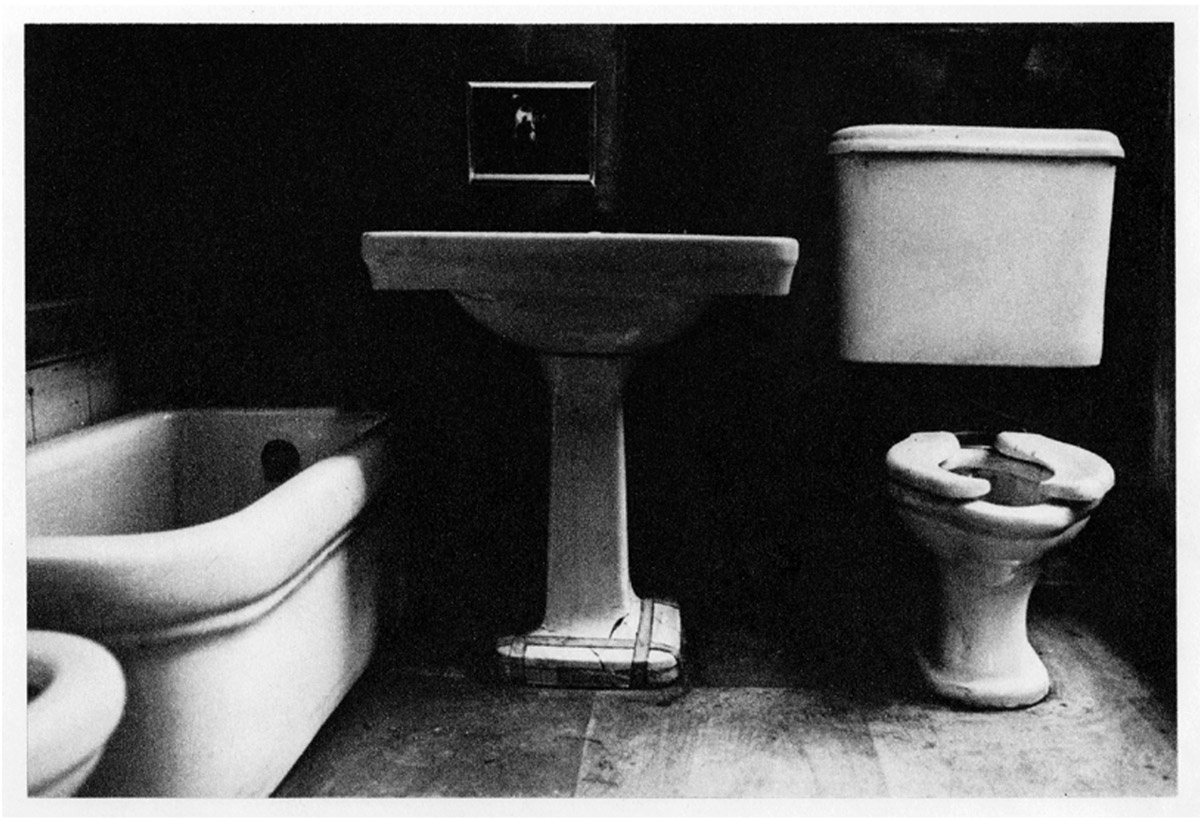

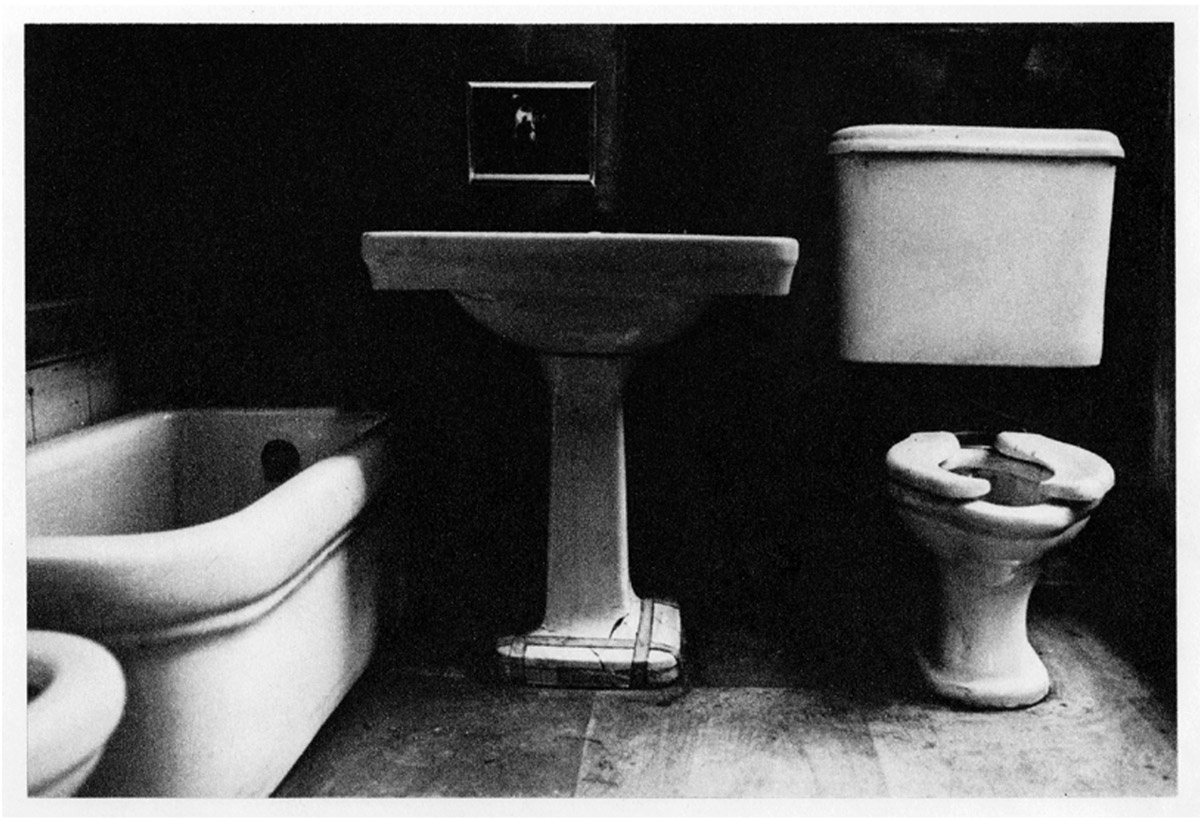

A nine-frame sequence that loops endlessly back on itself, beginning with a photograph of a bathroom and ending with the same image inside a book inside the same bathroom, creating an infinite visual paradox inspired by Magritte and Borges.

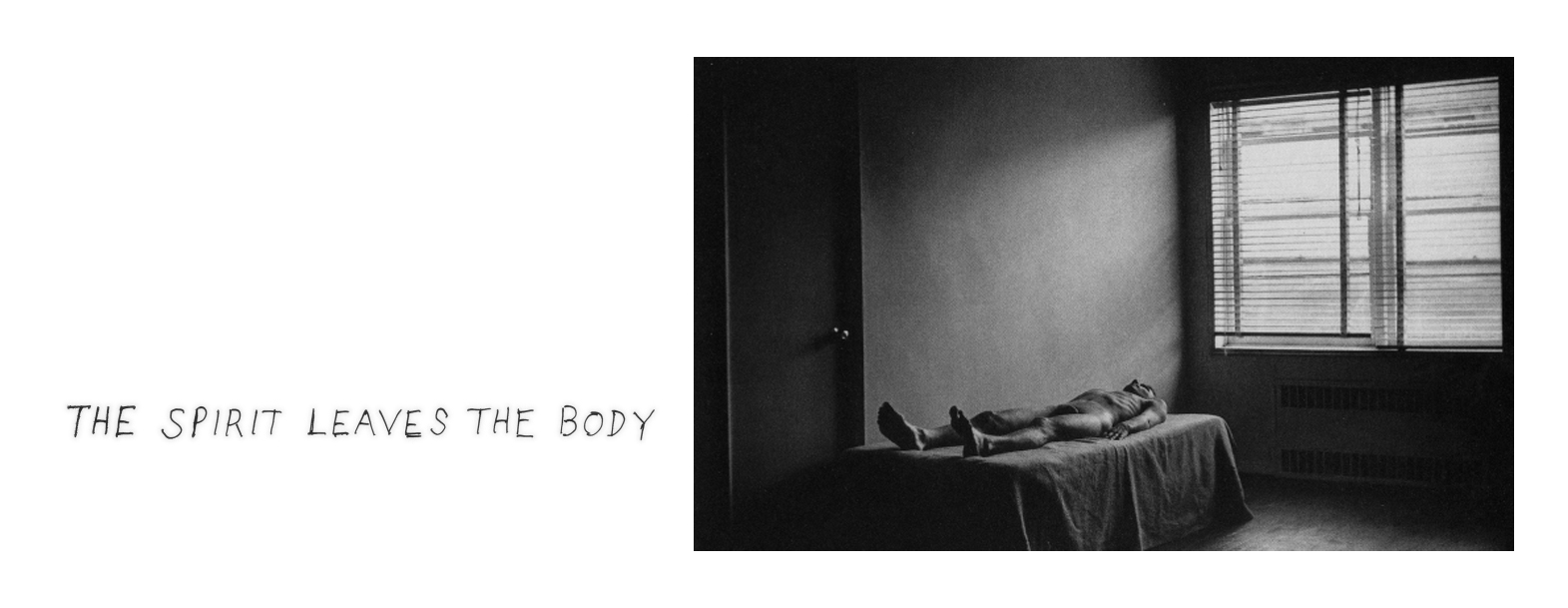

A six-frame sequence depicting a translucent figure rising from a sleeping body, using multiple exposures to visualise the departure of the soul — one of Michals's earliest and most iconic explorations of mortality and the unseen.

A single photograph of a couple in bed accompanied by Michals's handwritten text about love and evidence, becoming one of the most reproduced and emotionally resonant works in the history of art photography.

Born in McKeesport, Pennsylvania, a steel town south of Pittsburgh.

Travels to the Soviet Union and begins photographing for the first time, discovering his vocation with a borrowed camera.

Photographs René Magritte in Brussels, producing one of the most celebrated artist portraits of the century.

Begins creating photographic sequences, breaking with the convention of the single decisive image.

Publishes Sequences, the first major collection of his narrative photographic work.

Creates Things Are Queer, the self-referential nine-frame sequence that becomes his most widely exhibited work.

Publishes Real Dreams, consolidating his reputation as photography's foremost narrative innovator.

Major retrospective at the International Center of Photography in New York.

Publishes The Essential Duane Michals, a comprehensive career survey spanning six decades of work.

Interested in discussing photography, collaboration, or just want to say hello? I’d love to hear from you.

Contact →