Dorothea Lange was born in Hoboken, New Jersey, in 1895, the first child of a second-generation German-American family. At the age of seven she contracted polio, which left her with a permanent limp in her right leg. The experience marked her profoundly. Rather than retreating from the world, the disability gave her an acute sensitivity to the suffering of others and an instinctive identification with people who existed on the margins. She would later say that the limp was the most important thing that happened to her, shaping the way she moved through the world and the empathy that became the foundation of her art.

Her parents divorced when she was twelve, and she was largely raised by her mother and grandmother on the Lower East Side of Manhattan. After graduating from high school she announced her intention to become a photographer, despite having never owned a camera. She studied with Clarence White at Columbia University, one of the leading pictorialist photographers and teachers of the era, and also worked as an apprentice in several New York portrait studios, including that of Arnold Genthe. In 1918 she left New York and travelled west, eventually settling in San Francisco, where she opened a successful portrait studio catering to the city's wealthy families.

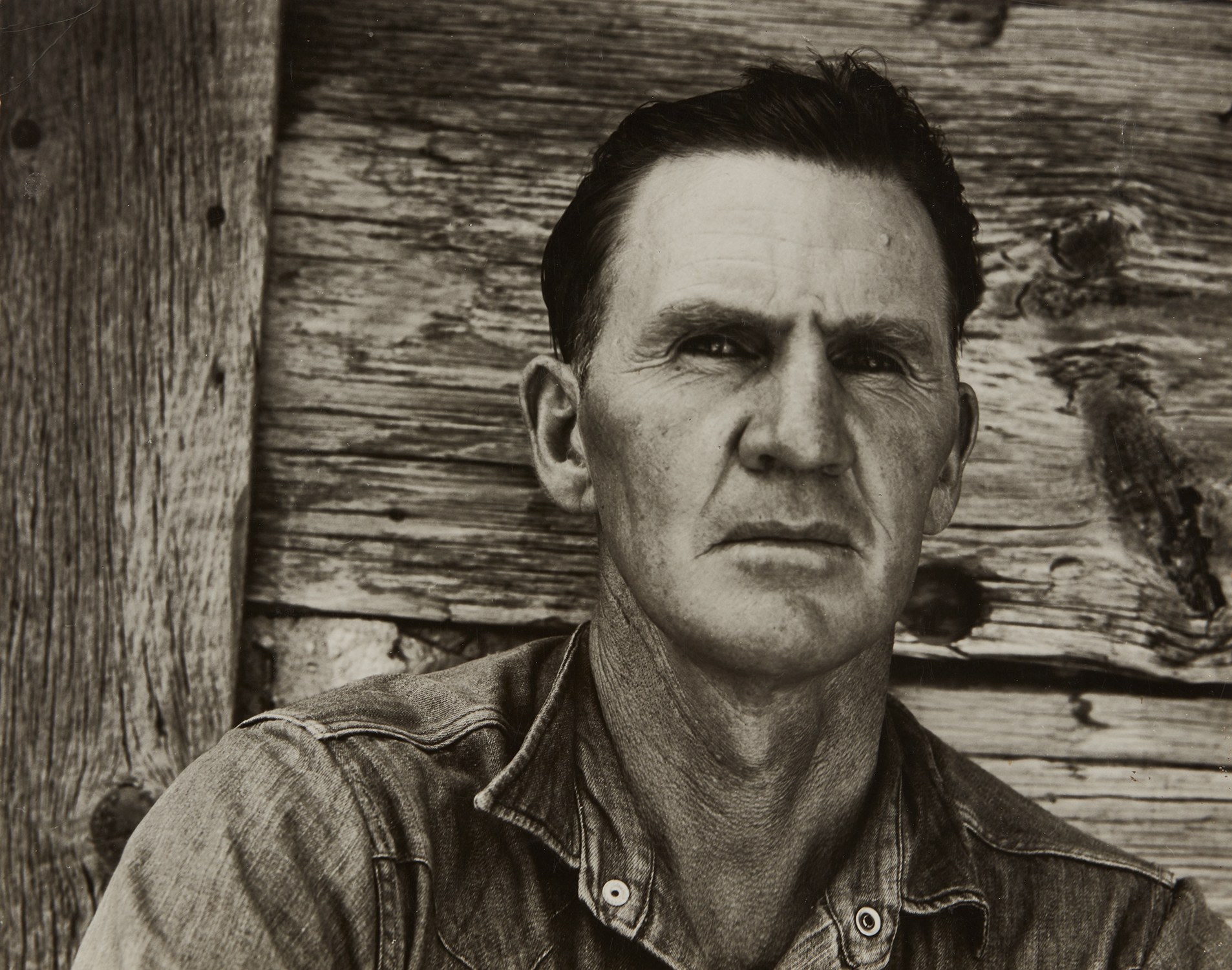

For more than a decade Lange built a prosperous career as a society portraitist, but the onset of the Great Depression in 1929 changed everything. From the window of her studio on Montgomery Street she could see the breadlines forming below, and the sight compelled her to abandon the safety of the studio and take her camera into the streets. Her 1933 photograph White Angel Breadline, depicting a solitary man with his back to the crowd, his hands clasped around a tin cup, announced the arrival of a new kind of documentary photographer: one who could transform a scene of collective despair into an image of individual dignity.

The photograph brought her to the attention of Paul Schuster Taylor, a professor of economics at the University of California, Berkeley, who was studying the effects of the Depression on California's agricultural workers. Taylor hired Lange to accompany him on fieldwork, and the two formed a partnership that was both professional and personal. They married in 1935, and for the rest of her life Taylor remained her closest collaborator, providing the social and economic context that gave her photographs their full meaning. Their joint work caught the attention of the federal government, and Lange was hired by the Farm Security Administration under the direction of Roy Stryker to document the conditions of displaced and impoverished Americans across the rural South and West.

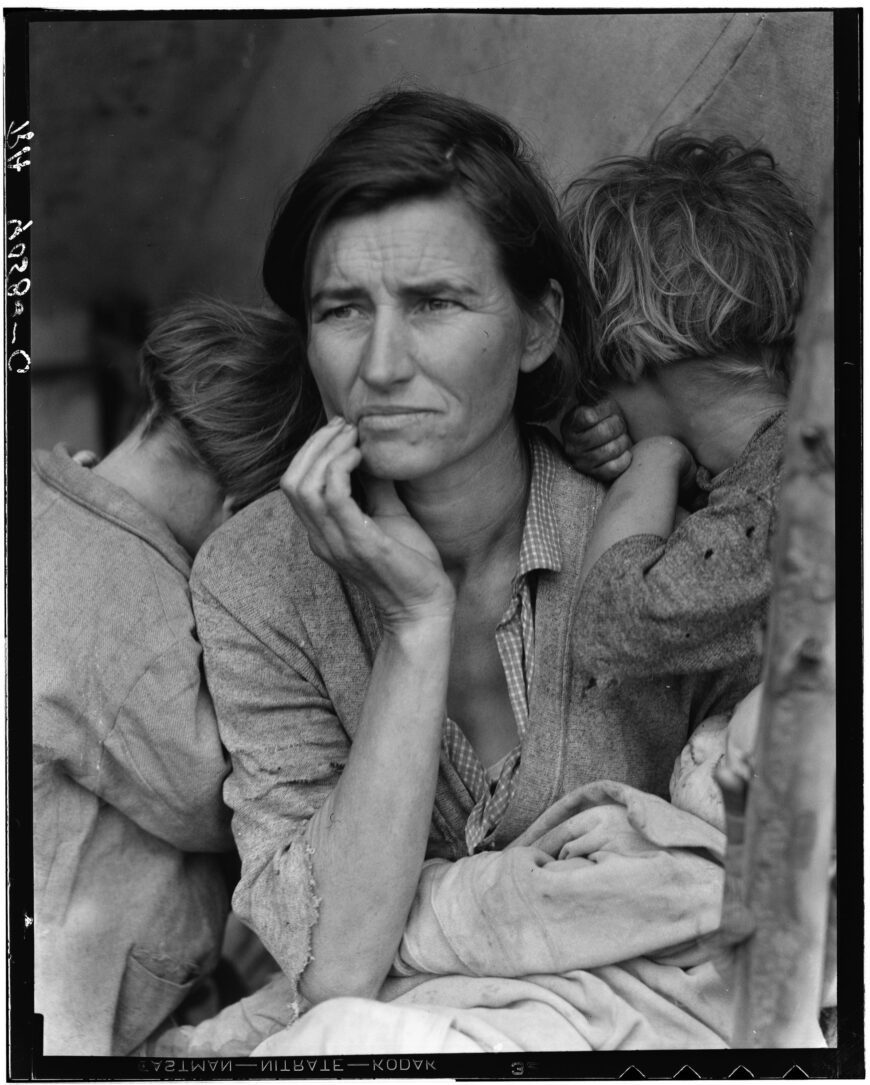

It was during this period that Lange made the photograph for which she is best remembered. In March 1936, driving past a pea-pickers' camp in Nipomo, California, she pulled over and approached a woman sitting in a lean-to tent with her children. The woman was Florence Owens Thompson, a thirty-two-year-old mother of seven whose family had been stranded when their car broke down. Lange made six exposures in roughly ten minutes, moving progressively closer, and the final frame became Migrant Mother, perhaps the most recognised photograph of the twentieth century. The image was published almost immediately, prompting the federal government to send emergency food supplies to the camp. It remains the defining image of the Depression era and a testament to the camera's power to provoke action.

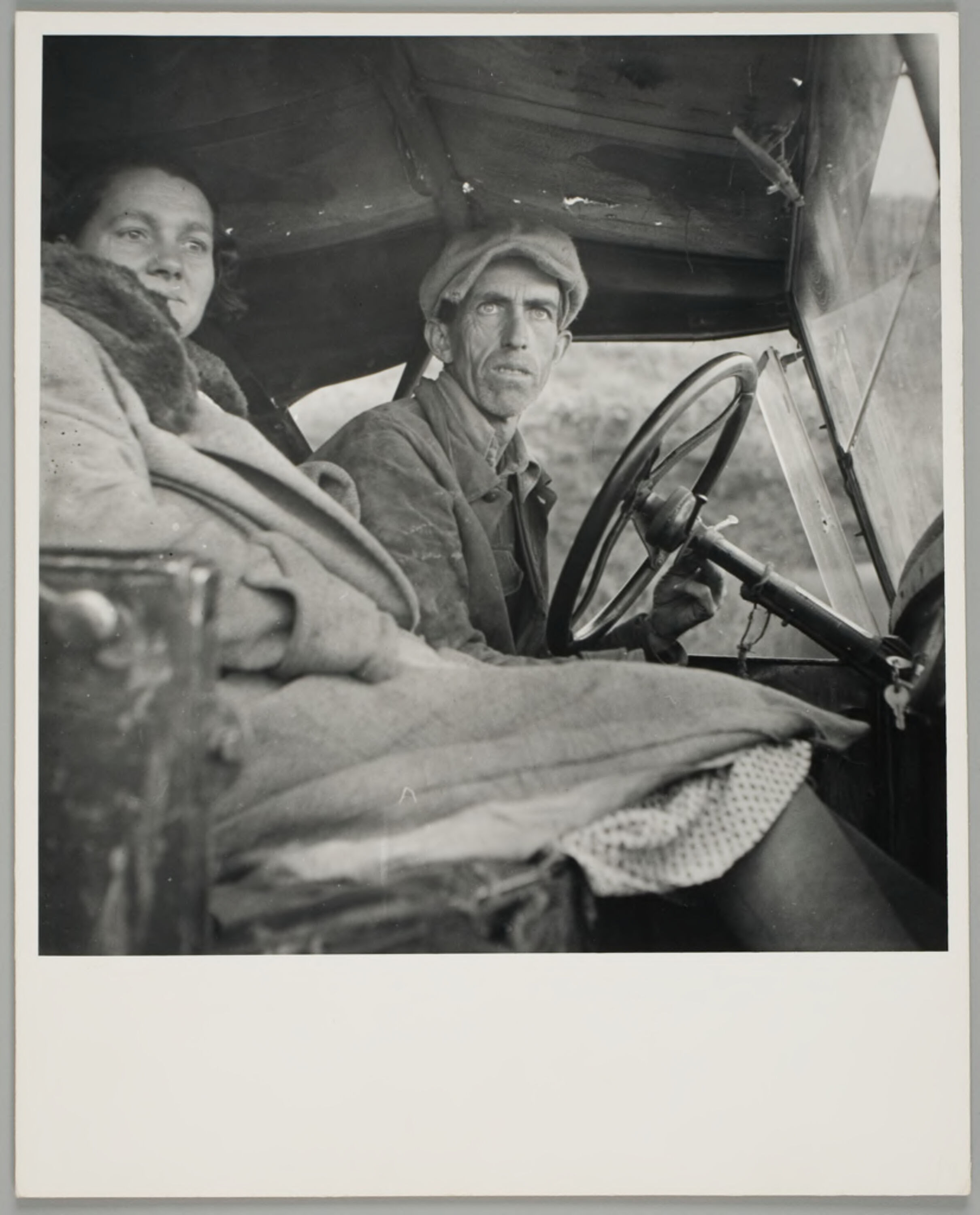

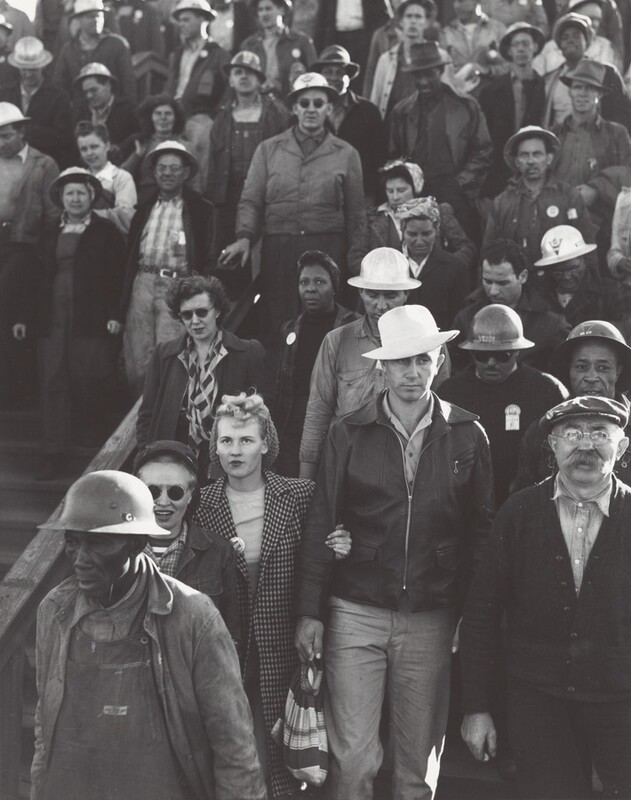

In 1939, Lange and Taylor published An American Exodus: A Record of Human Erosion, a pioneering book that combined photographs and field notes with economic analysis to document the Dust Bowl migration. The work anticipated the methods of later documentary projects and demonstrated that photographs and words together could tell a story that neither could tell alone. Then, in 1942, following the attack on Pearl Harbor and the signing of Executive Order 9066, Lange was hired by the War Relocation Authority to photograph the forced removal and internment of Japanese Americans on the West Coast. She approached the assignment with the same compassion she had brought to her Depression-era work, producing images that documented the fear, confusion, and quiet resilience of families being uprooted from their homes. The resulting photographs were so sympathetic to the internees that the United States Army impounded them, and they remained largely unseen for decades.

In the postwar years Lange's health, always fragile, continued to deteriorate, but she never stopped working. She became a freelance photographer for Life magazine in 1954, travelling to Asia and the Middle East on assignment, and she continued to photograph in and around the San Francisco Bay Area. Her later work showed a growing interest in the textures of everyday life: hands at work, faces in repose, the quiet rituals of family and community. In 1964, the Museum of Modern Art in New York began planning a major retrospective of her career, the first solo exhibition the museum had devoted to a female photographer.

Lange did not live to see the exhibition open. She died of oesophageal cancer in San Francisco on 11 October 1965, three months before the MoMA retrospective confirmed her status as one of America's greatest documentary photographers. Her legacy extends far beyond any single image. She proved that the camera could be an instrument of social justice, that photographs could move governments, and that empathy was not a weakness but a strength. Her influence can be traced through the work of every photographer who has turned a lens toward the dispossessed with the conviction that seeing is the first step toward change.