Portraitist of the extraordinary within the ordinary, fearless explorer of American identity, and one of the most original and unsettling photographers of the twentieth century.

1923, New York City – 1971, New York City — American

Diane Arbus changed the possibilities of the photographic portrait forever. Born Diane Nemerov in 1923 to a wealthy Jewish family that owned Russeks, a fashionable Fifth Avenue department store, she grew up insulated from the rougher textures of American life. That insulation became, paradoxically, the engine of her art. From an early age she felt drawn to the world beyond the margins of her privileged upbringing, to the people and places that polite society preferred not to see. Her photographs would spend the next two decades honouring that attraction with an intensity that remains without parallel.

At eighteen she married Allan Arbus, and together they ran a successful fashion photography business through the 1940s and 1950s, producing editorial work for magazines including Glamour, Vogue, and Harper's Bazaar. But commercial fashion held no lasting interest for Diane. She found the work stifling and began studying with Lisette Model at the New School for Social Research in 1956. Model's direct, confrontational approach to portraiture unlocked something in Arbus. She stopped assisting her husband's studio work and began photographing on her own, walking the streets of New York with a growing conviction that the camera could reveal what lay beneath the surface of ordinary human appearance.

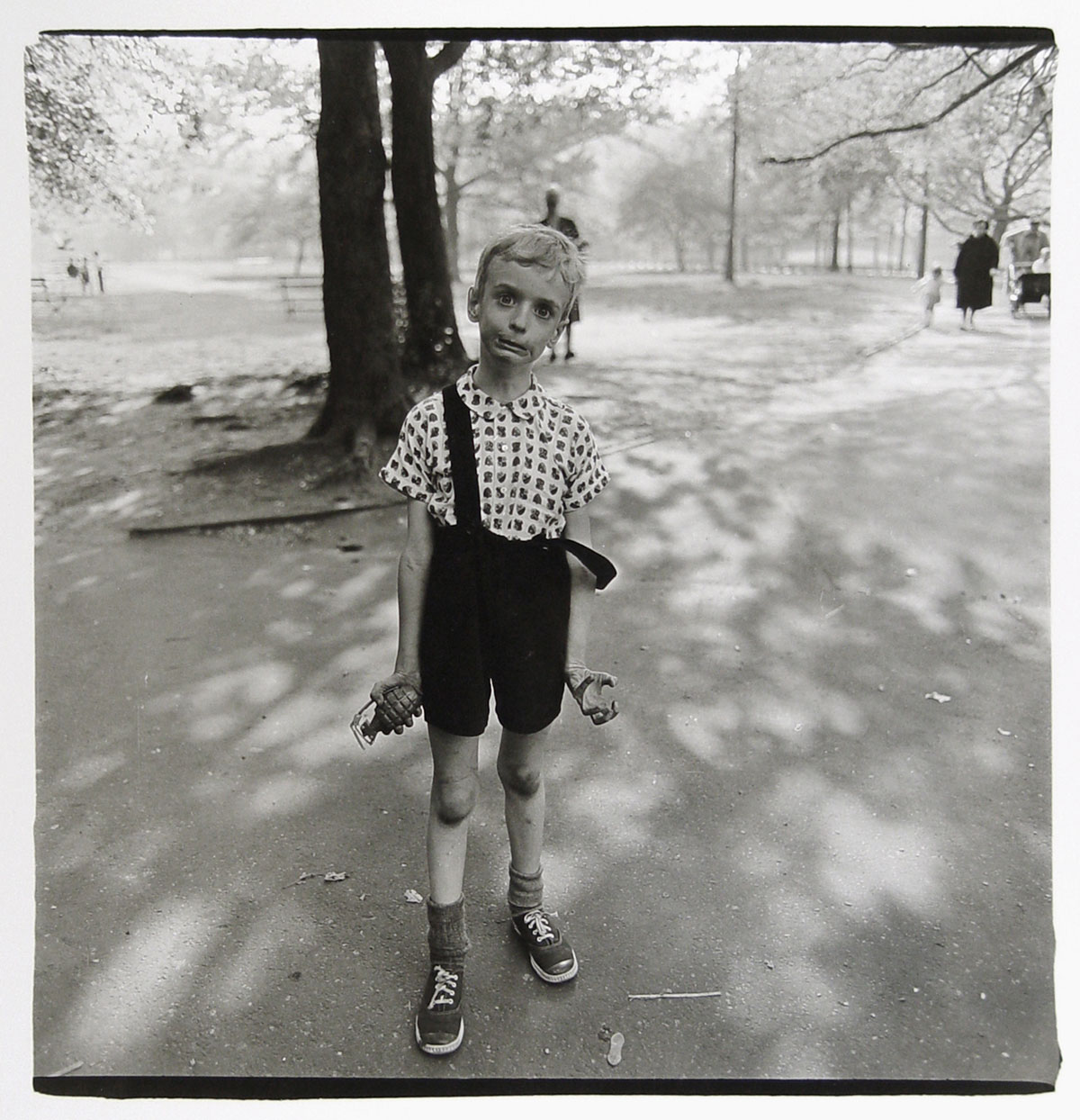

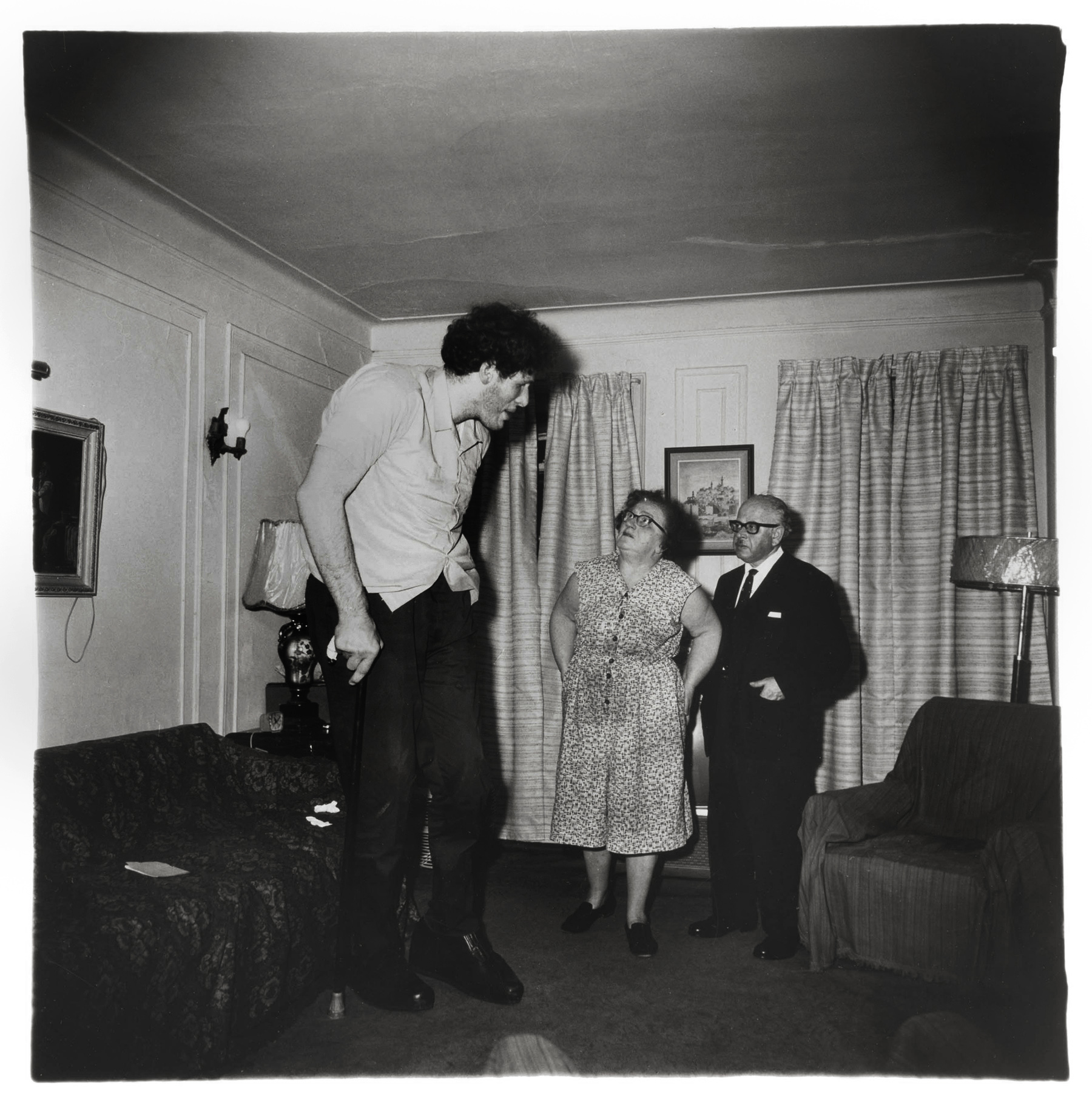

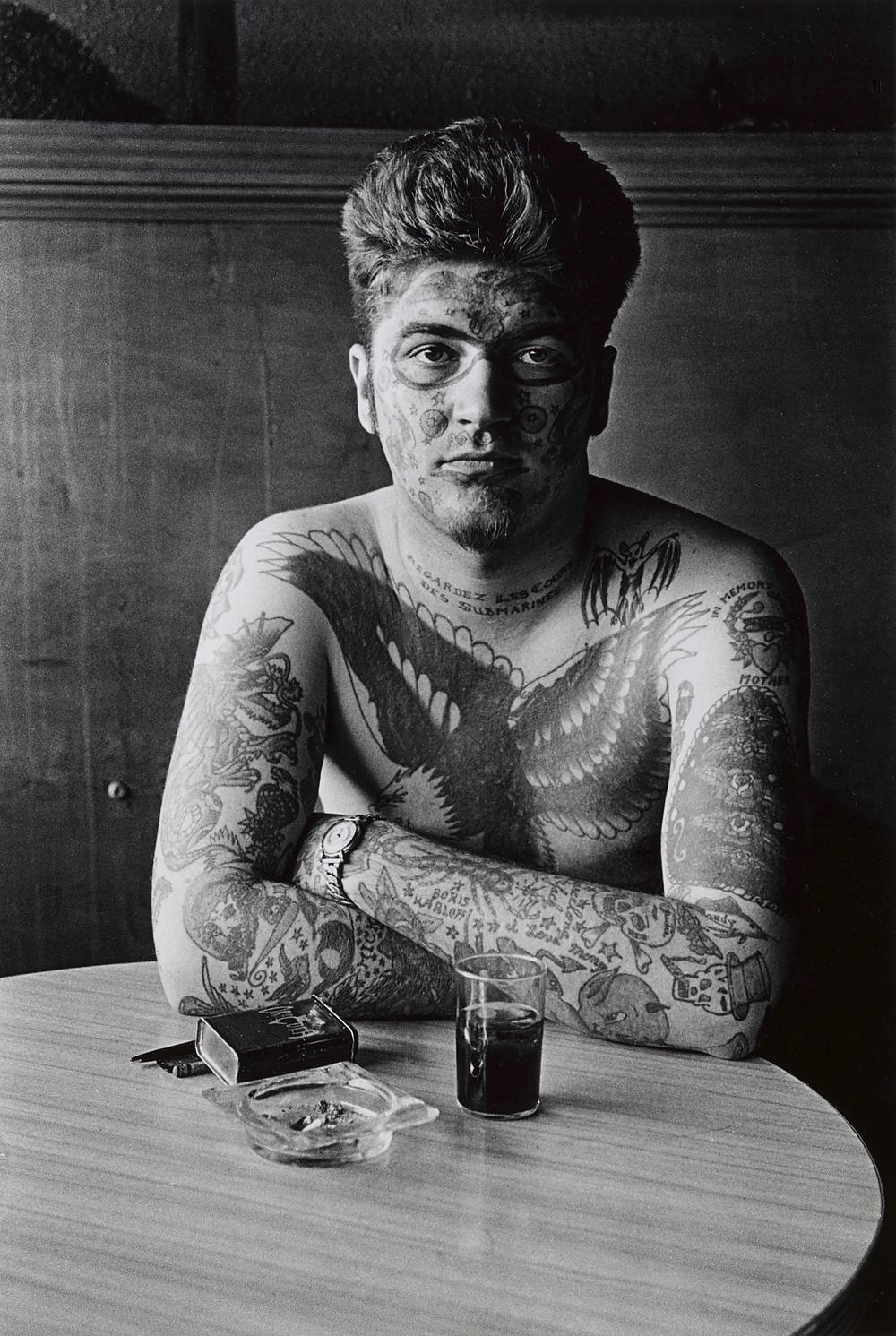

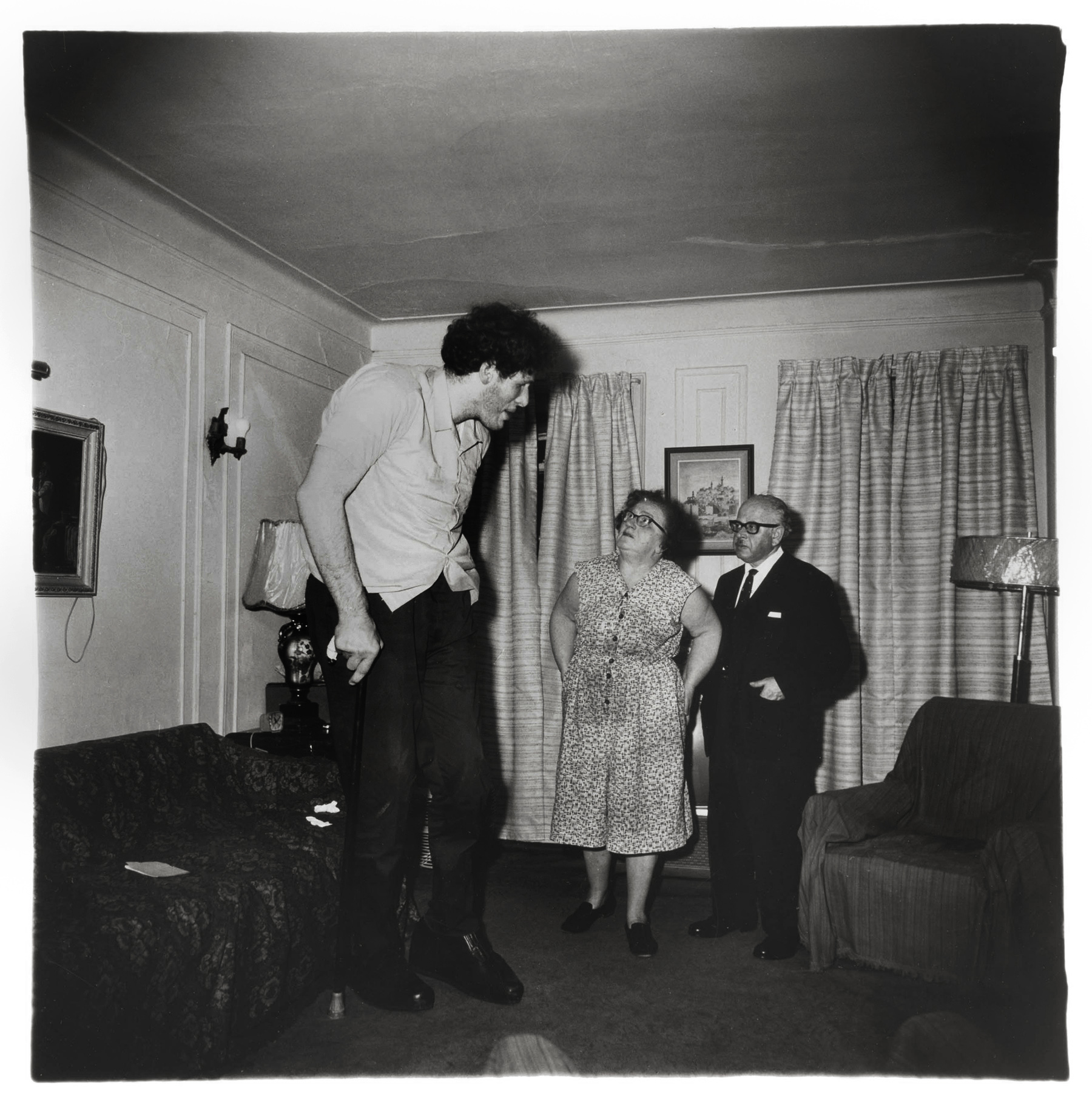

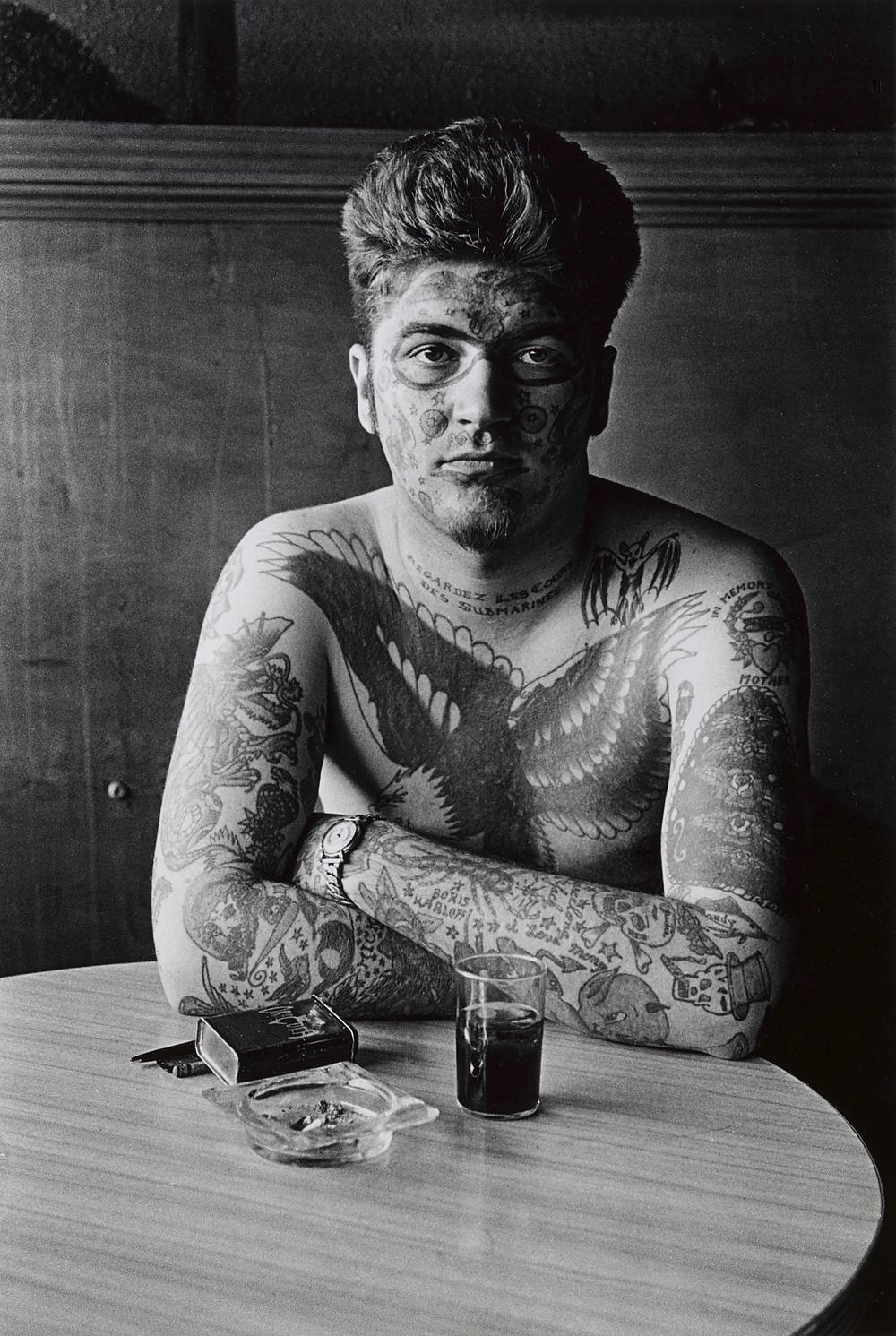

By the early 1960s, Arbus had developed the practice that would make her famous and infamous in equal measure. She sought out subjects on the margins of mainstream American life: sideshow performers, nudists, transvestites, identical twins, people with disabilities, and eccentrics of every description. But she also turned her lens on the supposedly normal, photographing suburban families, park-goers, and society matrons with the same penetrating attention. What emerged was not a simple division between freaks and normals but something far more unsettling: a vision in which everyone is strange, in which the surface of social identity is always slightly at odds with the person beneath it.

Her technique reinforced this vision. Working first with a 35mm Nikon and later with a twin-lens Rolleiflex that produced square-format negatives, Arbus typically positioned her subjects frontally, in the centre of the frame, looking directly at the camera. The resulting images have a quality of encounter, as though subject and viewer are meeting each other's gaze across a threshold that neither can quite cross. The flash, which she often used even in daylight, flattened the space and gave her subjects a stark, almost hallucinatory presence. There is no hiding in an Arbus portrait. The photograph refuses to let either its subject or its viewer look away.

Her work appeared in Esquire, Harper's Bazaar, The New York Times Magazine, and other publications throughout the 1960s, but it was her inclusion in the 1967 exhibition New Documents at the Museum of Modern Art, alongside Lee Friedlander and Garry Winogrand, that established her as one of the defining figures of a new photographic era. Curated by John Szarkowski, the show argued that a younger generation of photographers was using the documentary mode not to reform society but to explore their own relationship to it. Arbus's work was the most confrontational in the exhibition, and it drew the strongest reactions. Visitors were reported to have spat on her prints.

The controversy that surrounded Arbus in her lifetime has never entirely dissipated. Critics have debated whether her photographs exploit their subjects or dignify them, whether her attraction to difference was voyeuristic or empathetic, whether her unflinching gaze was cruel or compassionate. These arguments miss the complexity of the work itself, which resists easy moral categories. Arbus did not photograph her subjects from above or below. She photographed them face to face, and the resulting images carry the weight of a genuine human exchange, however brief and however fraught.

Arbus took her own life in 1971, at the age of forty-eight. The following year, she became the first American photographer to be included in the Venice Biennale. In 1972, the Museum of Modern Art mounted a posthumous retrospective that drew enormous crowds and cemented her reputation as one of the most important photographers of the twentieth century. The accompanying monograph, Diane Arbus: An Aperture Monograph, became one of the best-selling photography books ever published.

Her influence has been vast and deep, shaping the work of photographers as diverse as Nan Goldin, Mary Ellen Mark, Richard Avedon, Rineke Dijkstra, and Gregory Crewdson. She demonstrated that the portrait could be a space of radical encounter, a place where photographer and subject meet in mutual vulnerability, and where the viewer is compelled to confront the irreducible strangeness of another human being. That lesson continues to resonate in every photograph that takes the human face seriously.

A photograph is a secret about a secret. The more it tells you the less you know. Diane Arbus

The body of street portraits and environmental studies that defined her mature practice, culminating in the landmark 1967 MoMA exhibition alongside Friedlander and Winogrand.

Her final series, photographing residents of institutions for the developmentally disabled, producing images of haunting tenderness and ambiguity that remained unseen until 1995.

Pioneering photo-essays for Esquire, Harper's Bazaar, and The New York Times Magazine, bringing her unflinching portraiture to mainstream audiences.

Born Diane Nemerov in New York City to a prosperous family that owns the Russeks department store on Fifth Avenue.

Marries Allan Arbus at eighteen. Together they establish a fashion photography business serving major magazines.

Begins studying with Lisette Model at the New School for Social Research, a turning point that launches her independent practice.

Publishes her first major photo-essay in Esquire, establishing her reputation for portraits of people on the margins.

Receives a Guggenheim Fellowship to photograph American rites, manners, and customs. Renewed in 1966.

Included in the New Documents exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, curated by John Szarkowski.

Dies in New York City at the age of forty-eight.

Posthumous retrospective at MoMA becomes the most attended photography exhibition in the museum's history. Selected for the Venice Biennale.

Diane Arbus Revelations, a major retrospective and publication, opens at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and tours internationally.

Interested in discussing photography, collaboration, or just want to say hello? I’d love to hear from you.

Contact →