South Africa's most important photographer, whose meticulous, unflinching documentation of apartheid and its aftermath over six decades created an indispensable visual record of a society defined by racial division and the long, unfinished struggle for justice.

1930, Randfontein, South Africa – 2018, Johannesburg, South Africa — South African

David Goldblatt was born in 1930 in Randfontein, a gold-mining town on the Witwatersrand in South Africa, to Lithuanian Jewish immigrant parents who ran a small clothing shop. He grew up in the shadow of the mines whose wealth had built the region and whose labour practices — the systematic exploitation of black workers under conditions of near-servitude — were a microcosm of the racial oppression that defined South African society. Goldblatt's awareness of injustice was formed early, and it shaped the moral vision that would govern his photographic practice for the next six decades.

Goldblatt studied commerce at the University of the Witwatersrand but was drawn increasingly to photography. After his father's death in the early 1960s, he sold the family business and committed himself full-time to the camera. His decision was a deliberate act of moral purpose: Goldblatt understood that South Africa under apartheid was a society in which the structures of racial domination were embedded in every aspect of daily life — in the architecture, the urban planning, the transportation systems, the body language of its citizens — and he set out to document these structures with a precision and patience that few other photographers have matched.

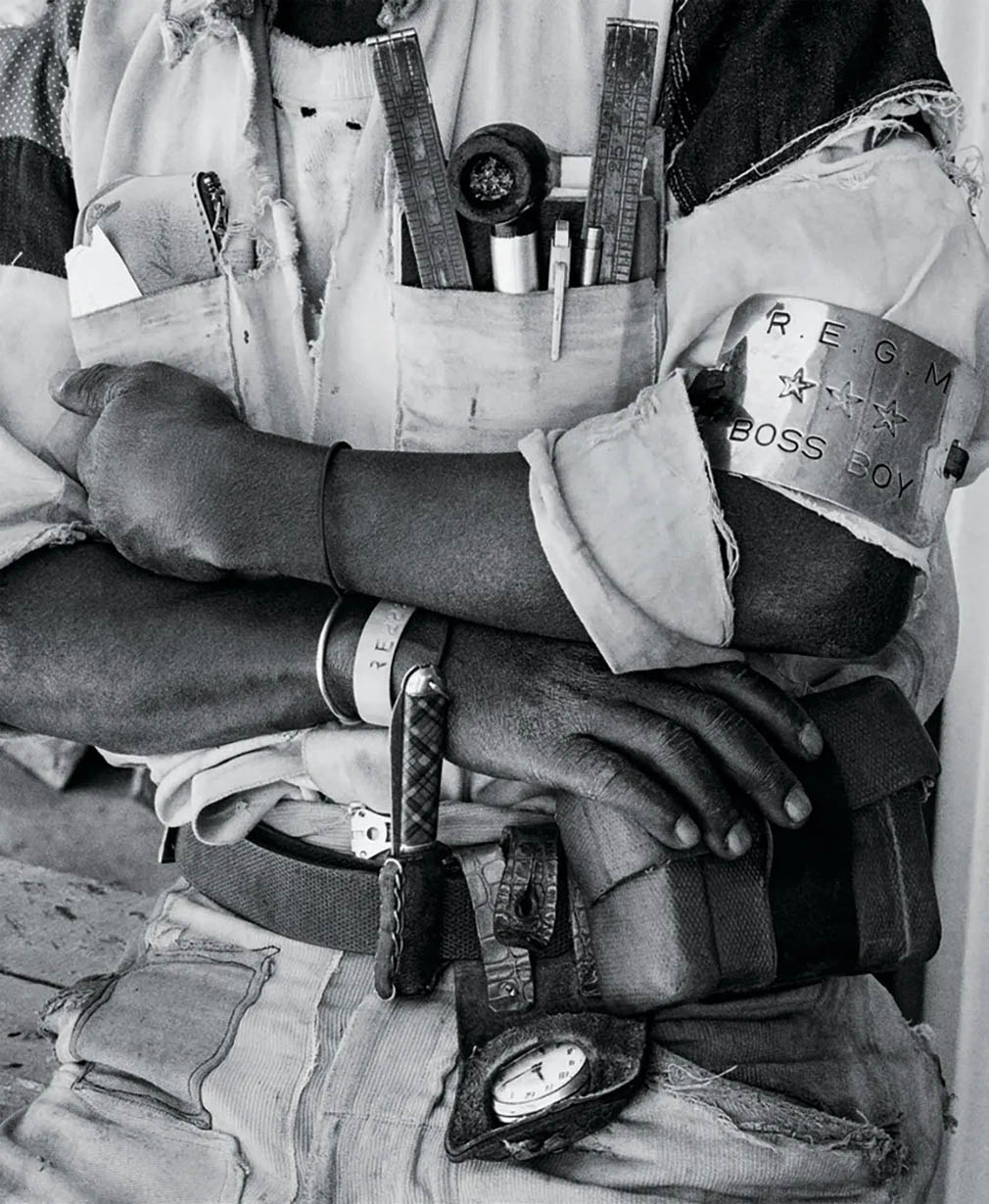

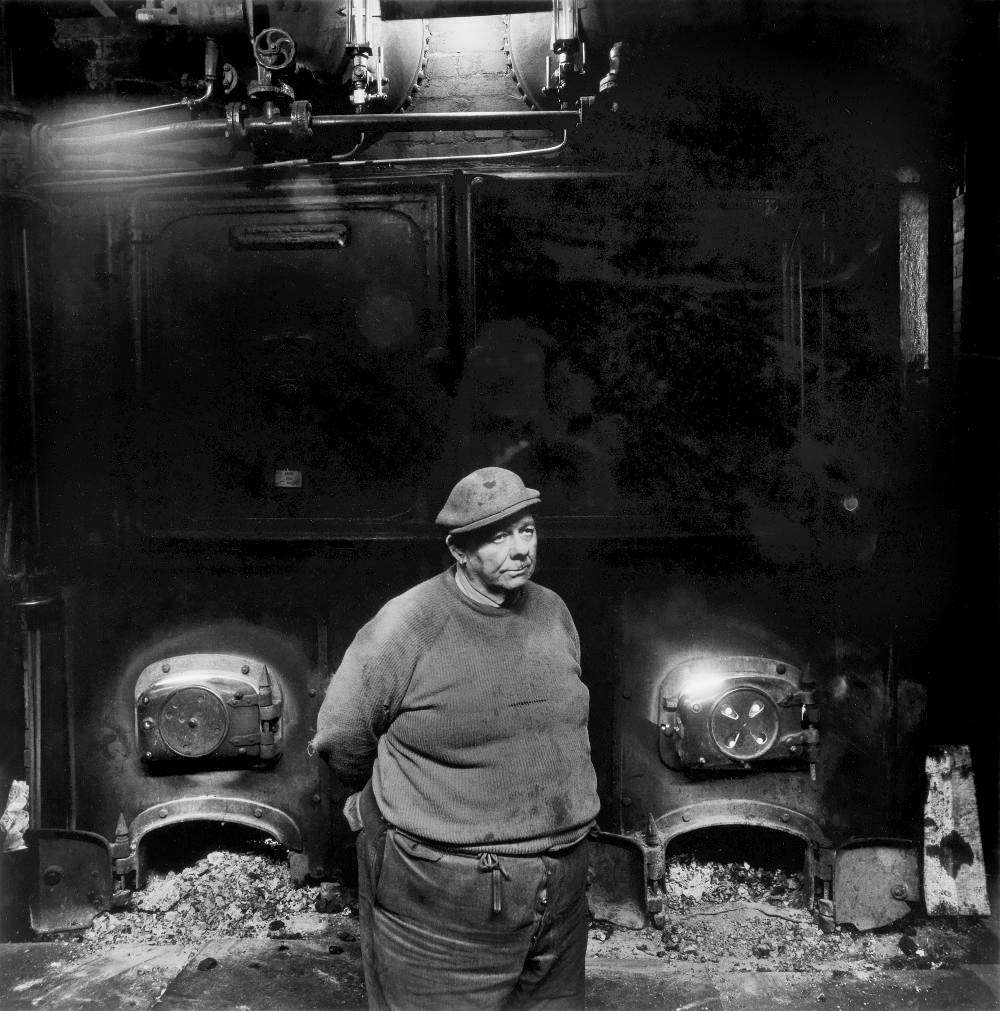

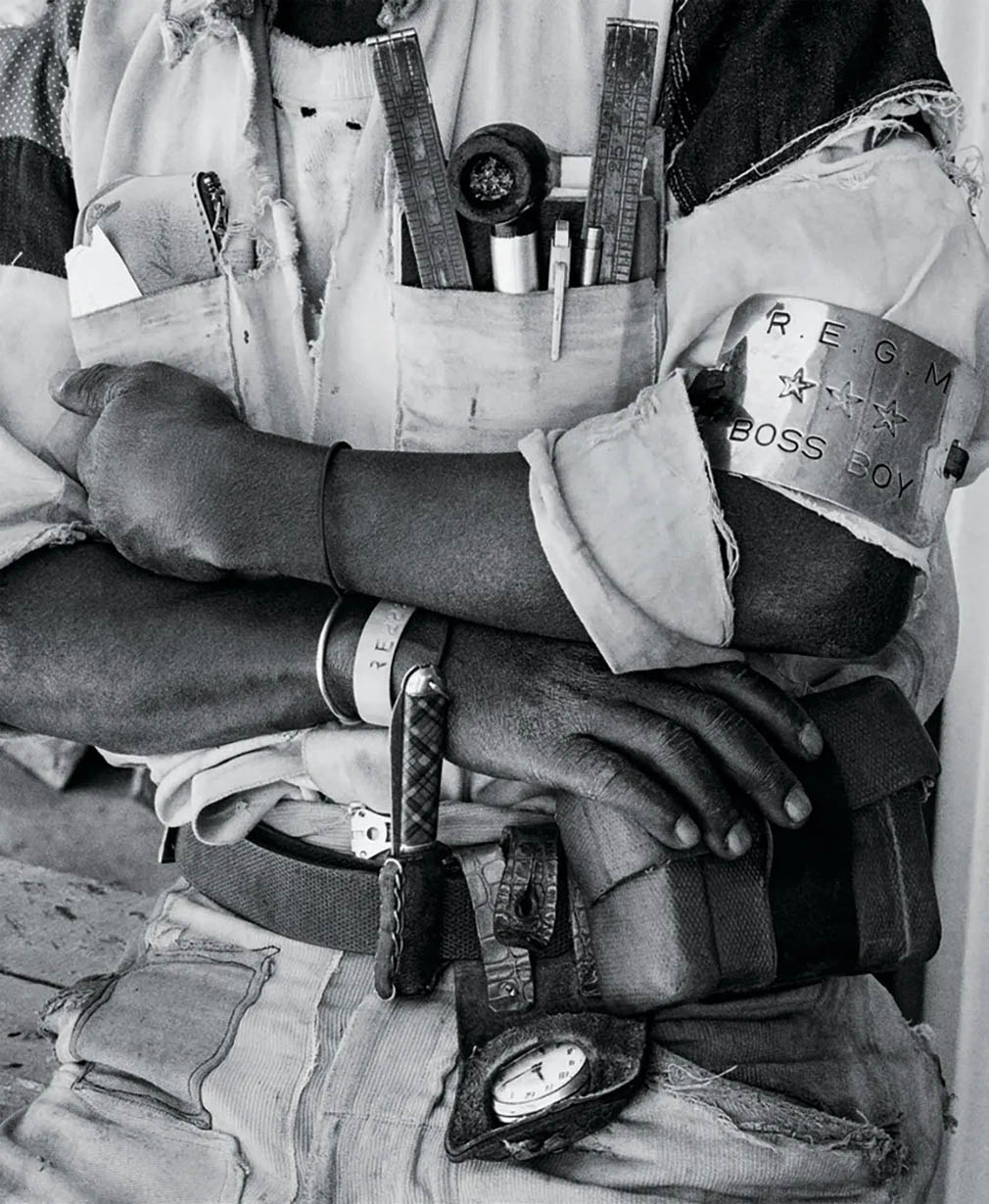

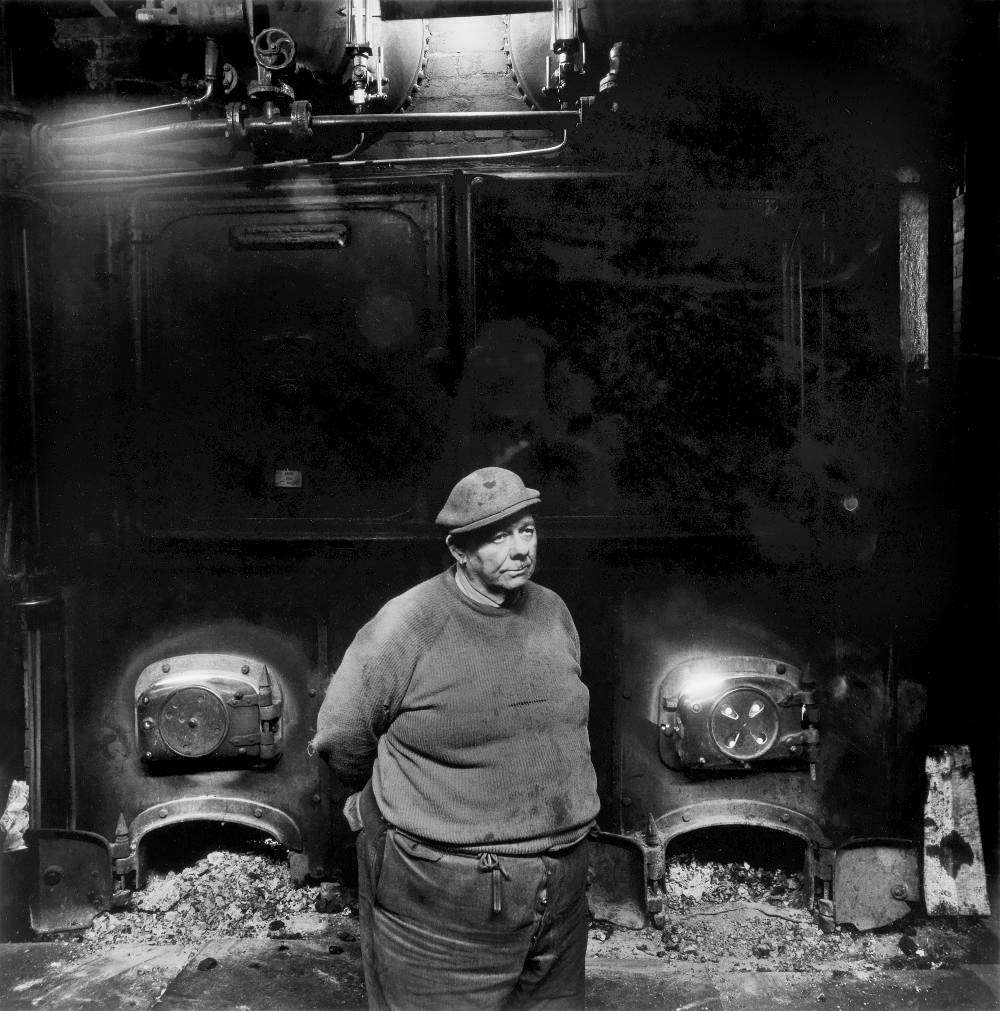

His first major book, On the Mines, published in 1973, documented the gold-mining industry of the Witwatersrand with a combination of technical rigour and humanistic concern. The photographs recorded the physical environment of the mines — the headgear, the shafts, the compounds — and the men who worked in them, black labourers whose lives were shaped by an industry that generated enormous wealth while denying them basic rights and freedoms. The book established Goldblatt's method: meticulous observation, a refusal of rhetoric or propaganda, and a faith that the careful recording of visible facts could reveal invisible structures of power.

In 1975, Goldblatt published Some Afrikaners Photographed, a work of extraordinary nuance and courage. Rather than depicting Afrikaners as the villains of the apartheid story, Goldblatt photographed them with the same care and empathy that he brought to all his subjects, documenting their customs, their domestic lives, their religious practices, and their relationship to the land. The book was controversial precisely because it refused simple moral categories: Goldblatt was interested not in condemning but in understanding, and his photographs revealed the human complexity behind the political structures. It remains one of the most important photographic documents of Afrikaner culture.

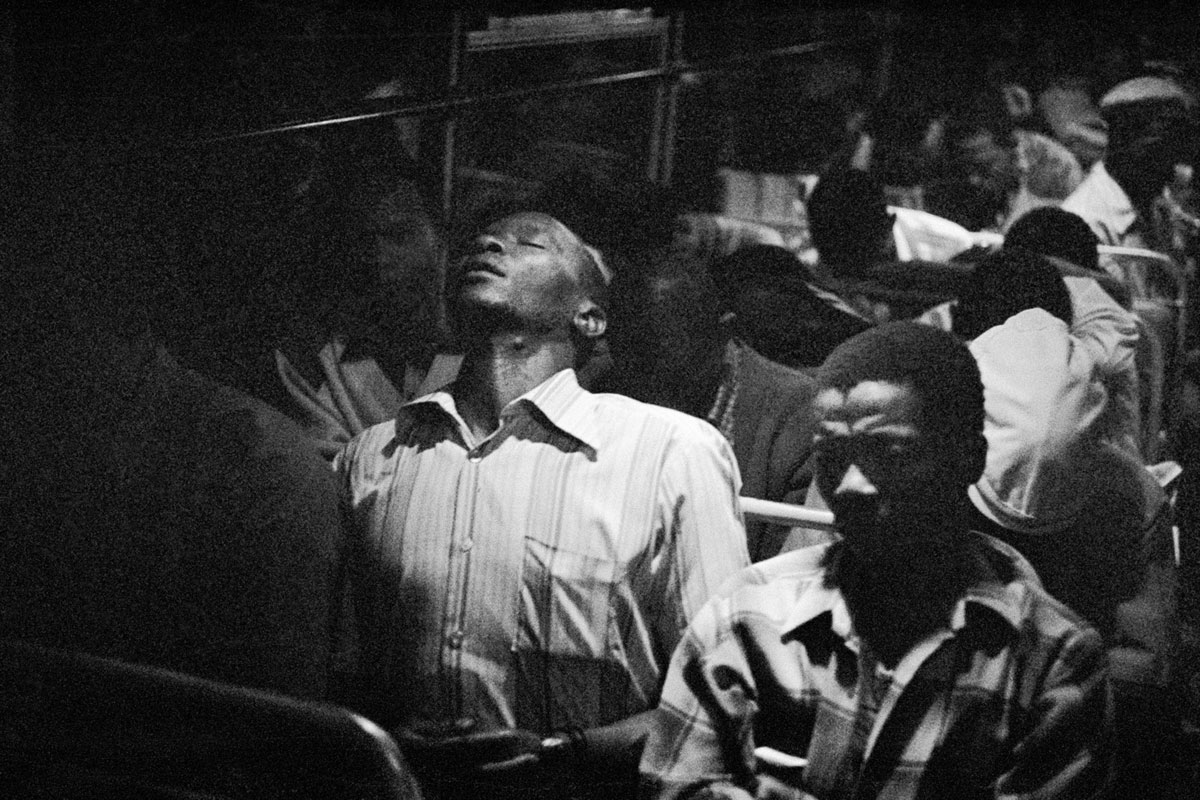

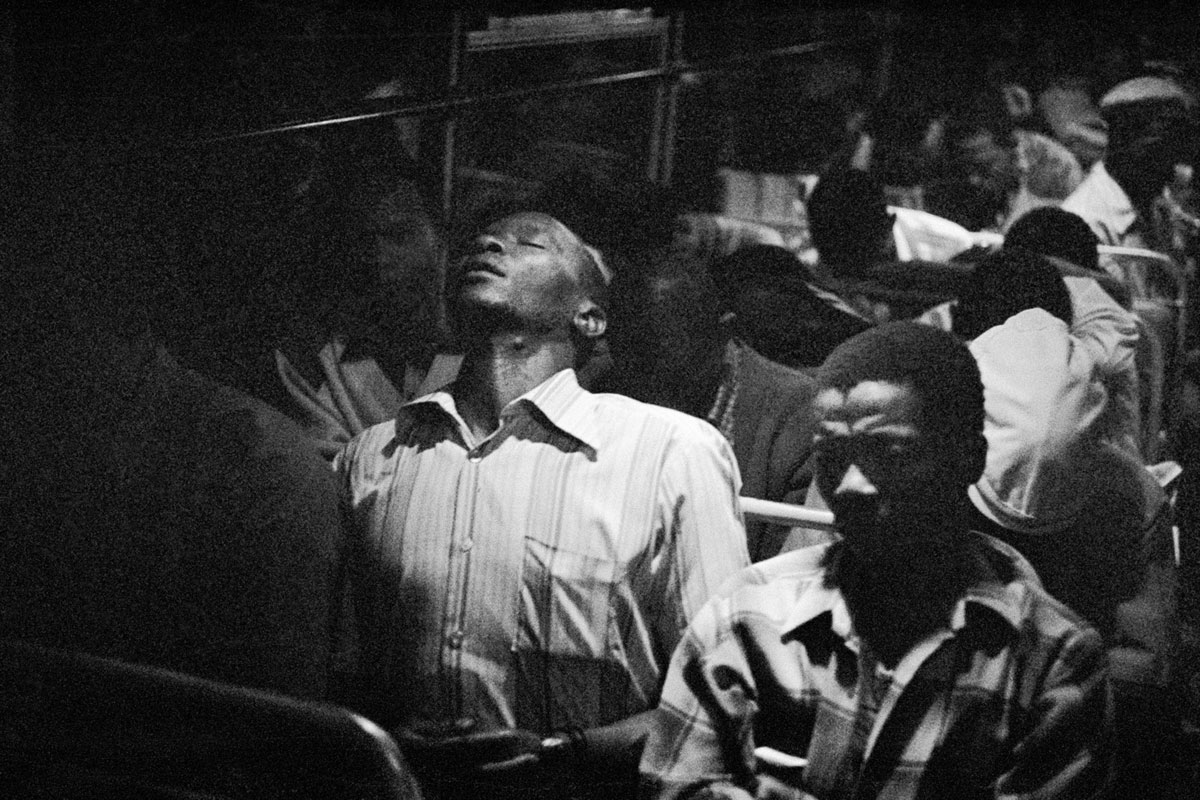

Perhaps Goldblatt's most devastating body of work is The Transported of KwaNdebele, published in 1989, which documented the daily ordeal of black workers who commuted up to eight hours a day by bus from the KwaNdebele homeland to their workplaces in Pretoria. The photographs of exhausted commuters, crammed into buses in the pre-dawn darkness, were a quiet indictment of the apartheid system's forced removals and the creation of homelands that were designed to keep the black workforce invisible while extracting its labour. The images are sober, patient, and devastating in their accumulation of evidence.

After the end of apartheid in 1994, Goldblatt continued to photograph South Africa with the same rigour and commitment, documenting the new democracy's struggles with inequality, poverty, crime, and the legacy of racial division. His later work, including Intersections and Intersections Intersected, expanded his practice to include colour photography and large-format work, and he explored the rapidly changing landscapes of Johannesburg with the same attention to the built environment and its social meaning that had characterised his earlier work.

Goldblatt was deeply committed to photography education in South Africa. In 1989, he founded the Market Photography Workshop in Johannesburg, an institution that provided photographic training to aspiring photographers from disadvantaged communities. The workshop produced a generation of important South African photographers and remains a lasting contribution to the country's cultural life.

David Goldblatt died in Johannesburg in 2018 at the age of eighty-seven. His body of work is unmatched in its sustained engagement with a single society over more than half a century, and his photographs constitute the most comprehensive visual record of South Africa under and after apartheid. He received honorary doctorates from the University of Cape Town and the University of the Witwatersrand, the Henri Cartier-Bresson Award, the Hasselblad Award, and the ICP Infinity Award, among many other honours. His legacy is that of an artist who believed that the patient, precise observation of visible reality could illuminate the invisible structures of injustice, and who devoted his life to proving it.

I have not been a campaigner. I have tried to find the structures, the values, the way of thinking that underlie the thing we call apartheid. David Goldblatt

A nuanced and courageous photographic study of Afrikaner culture and domestic life, refusing simple moral categories to reveal the human complexity behind apartheid's political structures.

A devastating documentation of black workers enduring eight-hour daily bus commutes from the KwaNdebele homeland, quietly indicting the apartheid system's forced removals and homeland policies.

An expansive body of colour and large-format work documenting the rapidly changing landscapes and social structures of post-apartheid South Africa, extending Goldblatt's lifelong engagement with the built environment.

Born in Randfontein, a gold-mining town on the Witwatersrand, South Africa, to Lithuanian Jewish immigrant parents.

After his father's death, sells the family business and commits to full-time photography, determined to document the structures of South African society under apartheid.

On the Mines published, documenting the gold-mining industry and its black labourers with technical rigour and humanistic concern.

Some Afrikaners Photographed published, a courageous and nuanced study of Afrikaner culture that refuses to reduce its subjects to political categories.

The Transported of KwaNdebele published. Founds the Market Photography Workshop in Johannesburg to train photographers from disadvantaged communities.

South Africa: The Structure of Things Then published, examining the architectural and spatial legacy of apartheid.

Awarded the Henri Cartier-Bresson Award, recognising his lifetime contribution to documentary photography.

Receives the Hasselblad Award, one of the most prestigious international honours in photography.

Dies in Johannesburg at the age of eighty-seven, leaving behind the most comprehensive photographic record of South Africa under and after apartheid.

Interested in discussing photography, collaboration, or just want to say hello? I’d love to hear from you.

Contact →