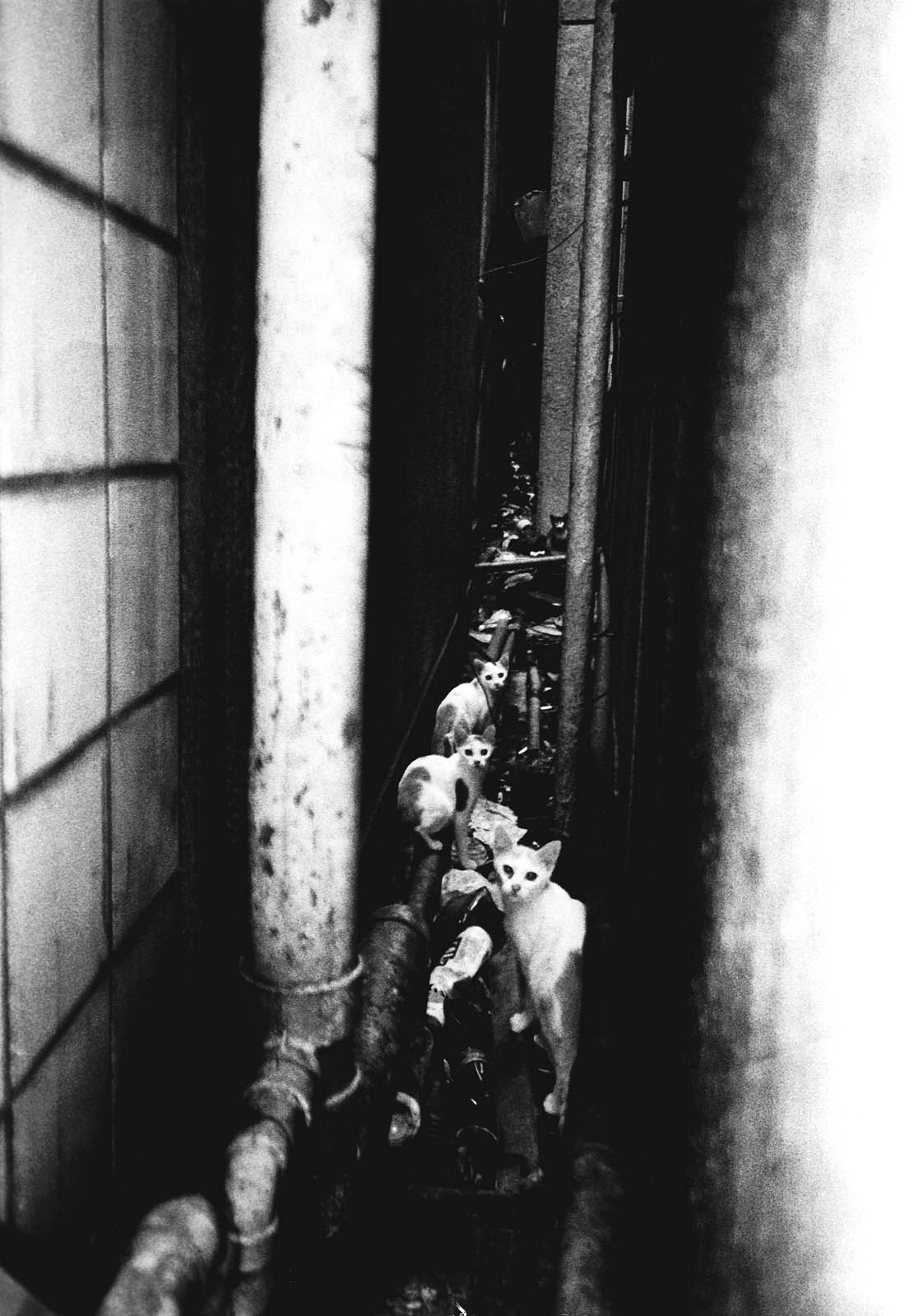

Stray Dog, Misawa, Aomori

1971

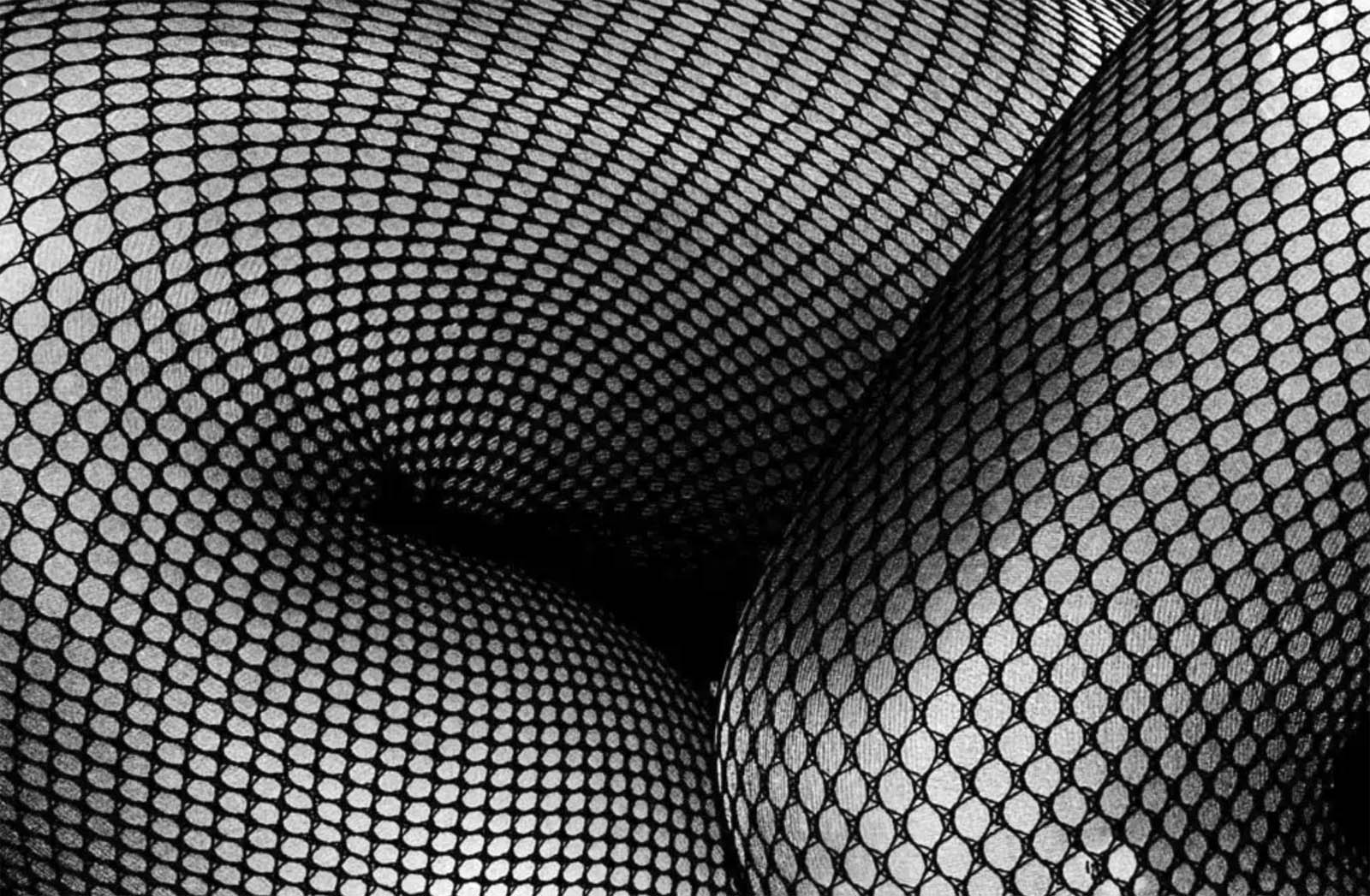

Shinjuku, Tokyo

1969

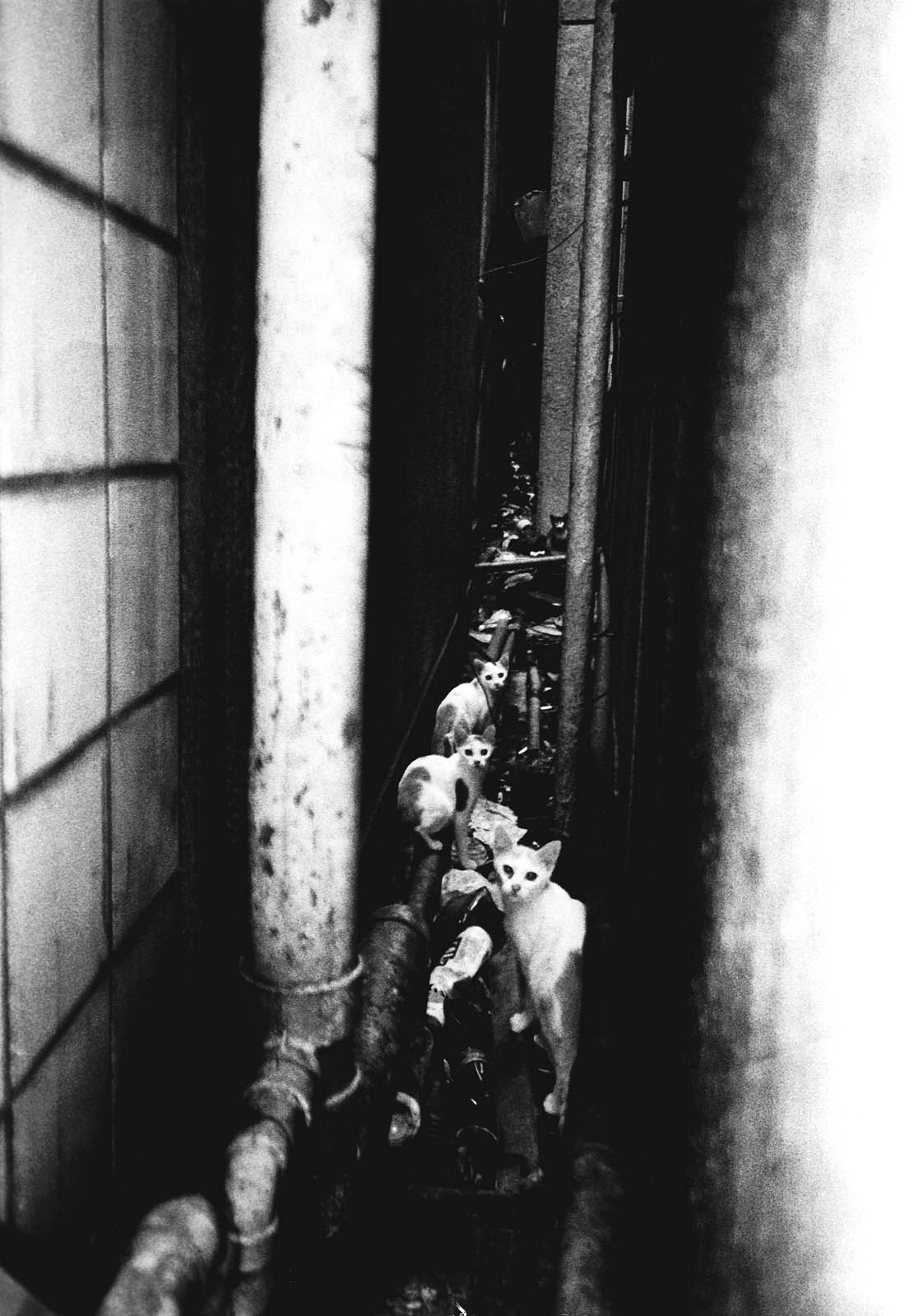

Shinjuku, Tokyo

c. 1970

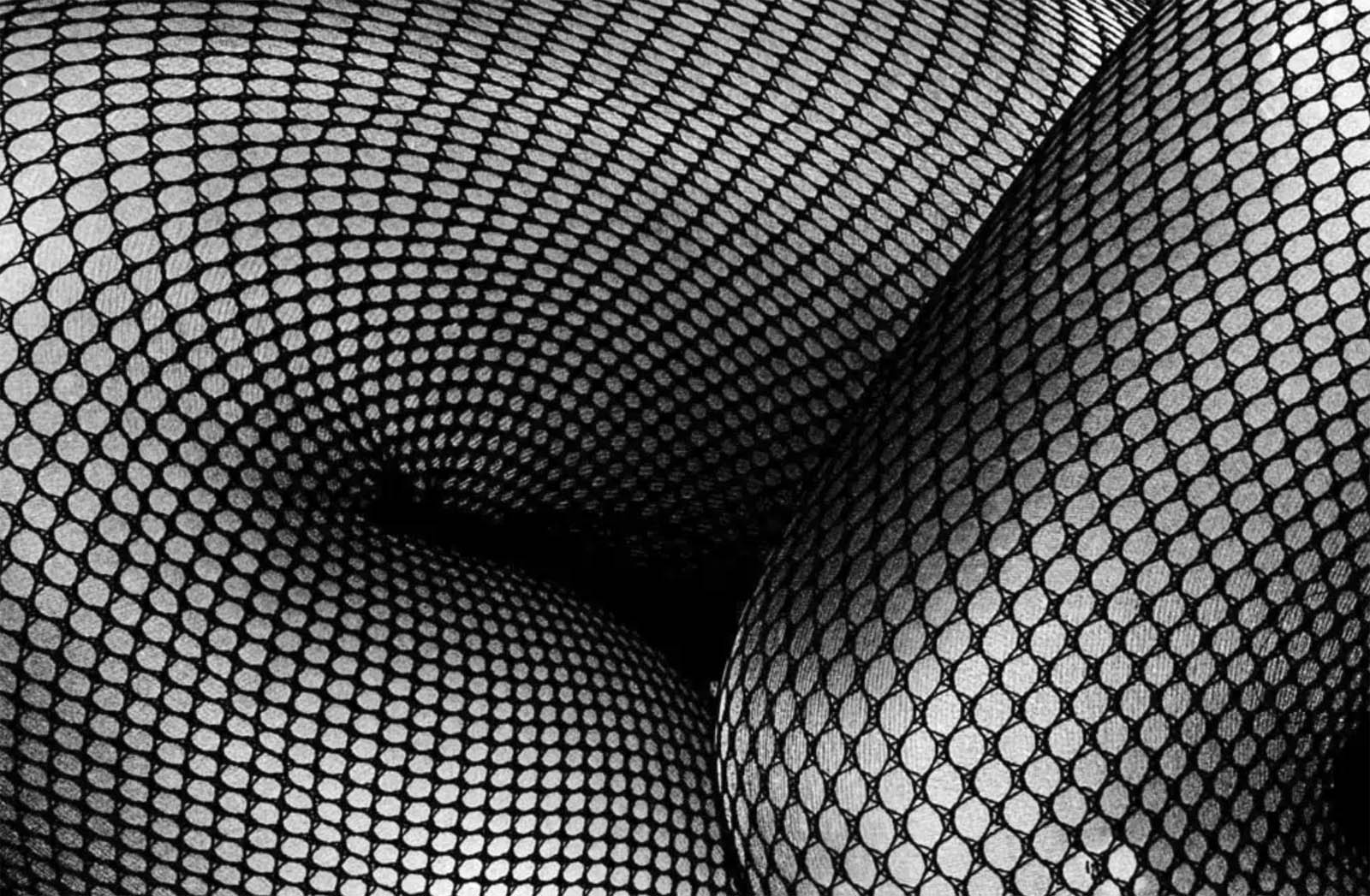

How to Create a Beautiful Picture 6

1987

Japan's most radical street photographer, whose high-contrast, grainy, blurred images of Tokyo's underbelly shattered every convention of photographic beauty and forged a raw new visual language from the chaos of the modern city.

1938, Ikeda, Osaka, Japan — Present — Japanese

Stray Dog, Misawa, Aomori

1971

Shinjuku, Tokyo

1969

Shinjuku, Tokyo

c. 1970

How to Create a Beautiful Picture 6

1987

Daidō Moriyama was born in 1938 in the industrial city of Ikeda, in Osaka Prefecture, Japan. His childhood was shaped by the upheavals of wartime and postwar reconstruction, and the restless energy of a nation remaking itself would become one of the defining currents of his art. As a young man, Moriyama had no particular ambition to become a photographer. He initially studied graphic design, drawn to the visual world through layout, typography, and commercial art. It was only when he encountered William Klein's photobook New York — with its raw, grainy, confrontational images of the American metropolis — that something shifted irreversibly. Klein's refusal of polish and convention struck Moriyama with the force of revelation, and he recognised in photography a medium capable of capturing the chaotic pulse of modern life in a way that design could not.

In 1961, Moriyama moved to Tokyo, the city that would become both his subject and his obsession. He found work as an assistant to Eikoh Hosoe, one of Japan's most experimental photographers, whose theatrical, surrealist imagery pushed the boundaries of the medium. Under Hosoe's tutelage, Moriyama absorbed the avant-garde energy coursing through Tokyo's art world, but he was already developing instincts that pulled in a different direction — away from the studio, away from the posed and the composed, and toward the raw disorder of the street. He began photographing compulsively, prowling the backstreets and entertainment districts of Tokyo with a compact camera, shooting from the hip, embracing accident, blur, and chance as creative principles rather than technical failures.

In 1968, Moriyama joined forces with Takuma Nakahira, Kōji Taki, and Yutaka Takanashi to co-found Provoke, a radical photography magazine that would become one of the most influential publications in the history of the medium. Though it lasted only three issues, Provoke articulated an aesthetic manifesto that shattered the conventions of Japanese photography. The group championed what they called are, bure, boke — rough, blurred, and out-of-focus — a deliberate rejection of technical perfection in favour of images that captured the fragmented, uncertain quality of contemporary experience. For Moriyama, this was not mere provocation but a philosophical position: the world itself was rough, blurred, and out-of-focus, and photography that pretended otherwise was lying.

The culmination of this radical period came in 1972 with the publication of Farewell Photography, a book so extreme in its destruction of conventional imagery that it remains shocking half a century later. Pages of near-abstract grain, blown-out highlights, smeared forms, and images pushed to the very edge of legibility announced Moriyama's willingness to annihilate photography itself in order to discover what might survive the destruction. The book was a sensation and a scandal, praised and condemned in equal measure. But its aftermath plunged Moriyama into a prolonged crisis. Having taken photography to its breaking point, he found himself paralysed by the question of what could possibly come next. Through the mid-1970s, he struggled with depression, creative doubt, and the feeling that he had exhausted the possibilities of his own medium.

Moriyama's recovery, when it came, took the form not of reinvention but of relentless repetition. He returned to the streets of Tokyo — above all to Shinjuku, the teeming entertainment district of neon signs, bars, strip clubs, alleyways, and anonymous crowds that had always been his spiritual home. He photographed obsessively, producing thousands upon thousands of images: stray dogs, legs in stockings, fragments of posters, reflections in shop windows, the faces of strangers caught in passing. His method was instinctive and physical, a form of hunting in which the camera became an extension of his nervous system. He shot quickly, without deliberation, trusting his body's reflexes more than his mind's calculations, and the resulting images carried the jittery, febrile energy of the city itself.

By the 1990s and into the new century, Moriyama's influence had spread far beyond Japan. Photographers such as Wolfgang Tillmans, Anders Petersen, and Antoine d'Agata acknowledged his impact on their own practice, and a new generation of street photographers around the world embraced the aesthetic of imperfection and immediacy that he had pioneered. His work was exhibited in major retrospectives at institutions including the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, the Tate Modern in London, and the Fondation Cartier in Paris. What had once been dismissed as anti-photography was now recognised as one of the most vital and original bodies of work in the medium's history.

Throughout his career, Moriyama has been extraordinarily prolific, publishing well over a hundred photobooks — a body of work unmatched in its sheer volume and sustained intensity. His books are not mere collections of images but objects in themselves, cheap and deliberately disposable in their production, reflecting his conviction that photography belongs not in galleries but in the hands of ordinary people, consumed quickly and without reverence. He has described his ideal photograph as something glimpsed from the window of a moving car or torn from a magazine and stuffed into a pocket — fleeting, democratic, and stubbornly resistant to the institutions of art.

Now in his eighties, Moriyama continues to photograph the streets of Shinjuku with undiminished energy, publishing new books and exhibiting worldwide. His daily routine remains essentially unchanged from his youth: he walks, he looks, he shoots. The city renews itself around him, but his hunger for its images never fades. In an era of digital perfection and algorithmic curation, Moriyama's grainy, imperfect, fiercely physical photographs stand as a reminder that the most powerful images are often those that refuse to be beautiful, choosing instead to be true.

I want to take photographs that are so powerful they make you feel like you've been hit. Daidō Moriyama

A radical deconstruction of the photographic image, pushing grain, blur, and high contrast to their absolute limits in a book that announced Moriyama's willingness to destroy photography in order to reinvent it.

The single image of a prowling dog in Misawa that became Moriyama's most iconic photograph and an emblem of his feral, instinctive approach to the streets.

Moriyama's decades-long obsession with Tokyo's entertainment district, documented in multiple books and exhibitions that together form an unparalleled portrait of urban desire, loneliness, and neon-lit excess.

Born in Ikeda, Osaka. Originally studies graphic design before turning to photography.

Moves to Tokyo and becomes assistant to Eikoh Hosoe, absorbing the experimental energy of the Japanese avant-garde.

Publishes his first photographs in the magazine Camera Mainichi, attracting attention for their raw, unconventional style.

Co-founds the radical photography magazine Provoke with Takuma Nakahira, Kōji Taki, and Yutaka Takanashi, championing the aesthetic of are, bure, boke.

Photographs Stray Dog in Misawa, creating the image that will become his most recognised work.

Publishes Farewell Photography, a book so radical in its destruction of conventional imagery that it provokes a crisis in his own practice.

Returns to prolific activity after a period of artistic doubt, producing a steady stream of books, exhibitions, and magazine work that continues for decades.

Major retrospective at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art brings his work to a broad international audience.

Awarded the Infinity Award for Lifetime Achievement by the International Center of Photography.

Continues to photograph the streets of Shinjuku daily, publishing new books and exhibiting worldwide, his output showing no diminishment of energy or vision.

Interested in discussing photography, collaboration, or just want to say hello? I’d love to hear from you.

Contact →