Claude Cahun was born Lucy Renee Mathilde Schwob in 1894 in Nantes, France, into a prominent Jewish intellectual family. Her uncle was the Symbolist writer Marcel Schwob, and her father was the publisher of a regional newspaper. The milieu in which she grew up was one of letters, ideas, and cultural ambition, and from an early age she demonstrated both a fierce intelligence and a profound discomfort with the identities that society assigned to her. As a teenager, she adopted the gender-neutral pseudonym Claude Cahun — a name that refused to declare its bearer male or female — and this act of self-reinvention would prove to be the founding gesture of an artistic career dedicated to the dismantling of fixed identity.

In her early twenties, Cahun moved to Paris with her lifelong partner and creative collaborator, Marcel Moore (born Suzanne Malherbe), who was also her stepsister. Their relationship, which was both romantic and artistic, defied the conventions of their era on every level. Together they created a body of photographic self-portraits that ranks among the most extraordinary and prescient artworks of the twentieth century. In these images, made primarily between the early 1920s and the late 1930s, Cahun appeared in an astonishing variety of guises: shaved-headed and androgynous, dressed as a dandy, a weightlifter, a doll, a Buddhist monk, a masked figure, a doubled reflection. Each portrait seemed to ask the same unsettling question: who is the person behind the performance? And each answered by suggesting that there was no stable self to be found — only an infinite series of masks, each concealing another mask beneath.

Cahun's photographic practice was deeply informed by the intellectual currents of her time. She was an active participant in the Surrealist movement, contributing to publications and exhibitions organised by André Breton and his circle. She shared the Surrealists' fascination with the unconscious, with dreams, and with the disruption of rational categories, but she brought to these interests a specifically gendered critique that the male-dominated movement often lacked. Where Breton and his male colleagues tended to treat women as objects of erotic fascination — muses, models, femmes fatales — Cahun insisted on being both the subject and the author of her own image. Her self-portraits were not made for the male gaze; they were acts of self-definition that challenged the very premise of a fixed, gendered self.

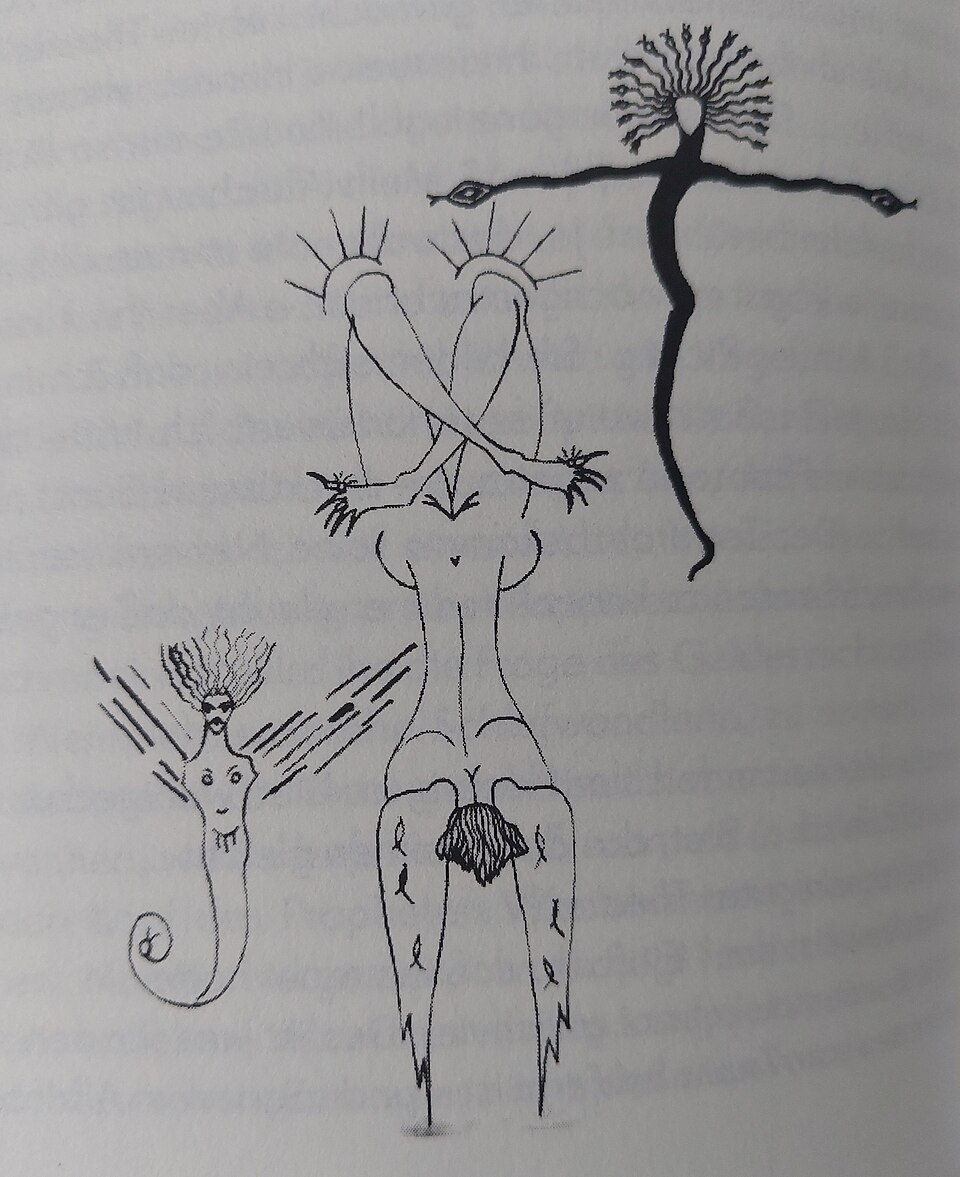

Her written work, particularly the autobiographical text Aveux non Avenus (Disavowals), published in 1930 with photomontages created in collaboration with Marcel Moore, extended these ideas into language. The book was a fragmented, poetic, deliberately contradictory autobiography that refused the conventions of coherent narrative, mirroring in text the refusal of stable identity that her photographs enacted visually. The photomontages that accompanied the text — kaleidoscopic assemblages of eyes, faces, body parts, and text — anticipated the strategies of feminist art by half a century and remain among the most visually arresting works of the Surrealist period.

In 1937, Cahun and Moore moved to the island of Jersey in the English Channel, seeking a quieter life away from the tensions of mainland Europe. When the German army occupied Jersey in 1940, the two women embarked on a remarkable campaign of resistance. They created handmade anti-Nazi leaflets, collages, and flyers, which they slipped into soldiers' pockets, left in cars, and distributed at military events. The propaganda was designed to demoralise the occupying troops and was signed with fictitious identities, transforming Cahun's lifelong practice of self-reinvention into an act of political subversion. In 1944, they were arrested by the Gestapo and sentenced to death. The sentence was never carried out — Jersey was liberated before it could be executed — but the experience of imprisonment and the threat of execution devastated Cahun's health.

Cahun died in Jersey in 1954, largely forgotten by the art world. It was not until the 1990s, when her photographic work was rediscovered and championed by scholars of gender theory, queer studies, and feminist art history, that she was recognised as one of the most radical and prescient artists of the early twentieth century. Her self-portraits, with their refusal of binary gender, their playful deconstruction of identity, and their insistence on the performative nature of selfhood, anticipate the work of Cindy Sherman, Nan Goldin, Gillian Wearing, and countless other contemporary artists who have explored the relationship between photography and identity. Cahun's legacy is that of an artist who understood, decades before the rest of the world caught up, that the self is not something we discover but something we construct — and that photography, with its unique capacity for fabrication and disguise, is the ideal medium for that act of construction.