Christian Boltanski was born in Paris in 1944, just days after the liberation of the city from Nazi occupation. His birth date was itself a kind of marker: he entered the world at the precise moment when France was beginning the long, painful process of reckoning with the trauma of war, collaboration, and the Holocaust. His father was a physician of Ukrainian Jewish origin who had survived the occupation by hiding beneath the floorboards of the family apartment, and the shadow of that concealment — of lives hidden, lost, and barely preserved — would permeate Boltanski's entire artistic practice. He was not, strictly speaking, a photographer, but photography stood at the centre of his work: not as a means of artistic expression in the conventional sense, but as a material, a relic, a trace of existence that could be manipulated, accumulated, and deployed in the service of memory and mourning.

Boltanski was largely self-taught. He never attended art school, and he began making art as a teenager, initially producing short films and artist's books that combined autobiography with fiction in ways that deliberately blurred the boundary between truth and invention. By the late 1960s, he had begun working with photographs — not photographs he had taken himself, but found photographs, snapshots, school portraits, obituary pictures, and other anonymous images salvaged from the detritus of ordinary lives. These images became the raw material for installations that explored the nature of memory, the passage of time, and the vulnerability of individual identity in the face of history's vast impersonal forces.

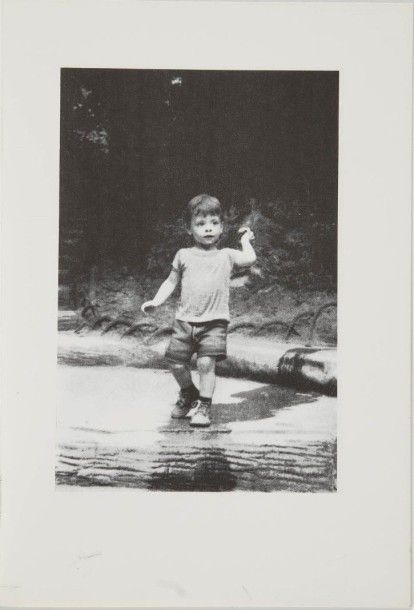

His breakthrough works of the 1970s and 1980s established the vocabulary that would define his career. In pieces such as 10 Portraits Photographiques de Christian Boltanski (1972), he presented rephotographed images of himself at various ages, blurred and degraded to the point where the individual features dissolved into anonymity. The technique became a signature: by enlarging, rephotographing, and reprinting found images until they lost their specificity, Boltanski transformed particular faces into universal symbols of mortality and loss. The resulting images possessed a spectral quality — recognisably human but stripped of the details that would connect them to specific identities.

In the late 1980s, Boltanski began creating the large-scale installations for which he is best known. Works such as Monument (1986) and Altar to the Chases High School (1987) combined rephotographed portraits with bare light bulbs, tin biscuit boxes, and other humble materials to create shrine-like assemblages that evoked both religious devotion and forensic evidence. The portraits, often of children, were arranged in grids or clusters and illuminated by naked bulbs whose wires trailed across the walls like veins or arteries. The effect was deeply unsettling: the viewer was confronted with the faces of people who might or might not be alive, might or might not be victims, in settings that suggested both memorial chapels and scenes of bureaucratic classification. The implicit reference to the Holocaust was unmistakable, though Boltanski insisted that his work addressed not any single historical event but the universal human experience of loss and the inadequacy of memory.

His installation The Reserve of Dead Swiss (1990) exemplified his method. Using obituary photographs clipped from Swiss newspapers — portraits of people who had died of natural causes in one of Europe's most peaceful and prosperous countries — Boltanski assembled a wall of small, blurred faces, each enclosed in a rusted tin frame and lit by a single desk lamp. The work's power lay in its deliberate ordinariness: these were not victims of atrocity but ordinary people who had lived and died in unremarkable circumstances, and yet the accumulation of their faces, degraded almost beyond recognition, produced an overwhelming sense of collective loss. By choosing Swiss subjects rather than Holocaust victims, Boltanski universalised his theme: death, he seemed to say, is not the property of history's great catastrophes but the shared condition of every human life.

In the twenty-first century, Boltanski's work expanded in scale and ambition. Personnes (2010), created for the Monumenta exhibition at the Grand Palais in Paris, filled the vast glass-roofed hall with tonnes of discarded clothing, arranged in rectangular plots that evoked both a refugee camp and a mass grave. A giant mechanical claw repeatedly lifted bundles of clothing from a central mound and dropped them, an image of random fate that reduced individual lives to interchangeable remnants. No Man's Land (2010) at the Park Avenue Armory in New York employed a similar vocabulary of discarded garments and mechanical repetition. And Les Archives du Cœur (The Archives of the Heart), begun in 2008, invited people around the world to record their heartbeats, creating a permanent archive on the Japanese island of Teshima — a memorial to the living that would outlast every contributor.

Boltanski died in Paris in 2021 at the age of seventy-six. His legacy is that of an artist who understood, more deeply than almost any of his contemporaries, the relationship between photography, memory, and death. In his hands, the photograph was never a record of presence but always an index of absence — a trace of someone who was once here and is here no longer. His work reminds us that every photograph is, in its essence, a memorial: a fragile, inadequate, but irreplaceable attempt to preserve the existence of those who will inevitably be forgotten.