The uncompromising British photographer who spent decades documenting the industrial decline of northeast England, producing one of the most powerful records of working-class life in the history of the medium.

1946, Douglas, Isle of Man – 2020, Cambridge, Massachusetts — British

Chris Killip was born in 1946 on the Isle of Man, a small island in the Irish Sea whose isolation and self-contained culture shaped his early understanding of community and place. His father ran a pub, and the young Killip left school at sixteen with no particular direction. In 1964, at the age of eighteen, he saw a copy of Henri Cartier-Bresson's The Decisive Moment in a local library and was struck with the sudden, life-altering conviction that photography was what he wanted to do. He moved to London and found work as an assistant to commercial photographers, learning the technical craft while spending every spare hour studying the photographic collections at the Victoria and Albert Museum.

In 1969, Killip received a commission from the Arts Council of Great Britain to photograph the Isle of Man, producing his first sustained body of work. The resulting images revealed an already mature sensibility: a commitment to black and white, an instinct for the monumental in the ordinary, and a refusal to sentimentalise or prettify his subjects. But it was his decision in the early 1970s to move to the northeast of England — to Newcastle upon Tyne and the surrounding industrial towns of Tyneside, Wearside, and the Durham coalfields — that would define his life's work and produce one of the most significant photographic projects of the twentieth century.

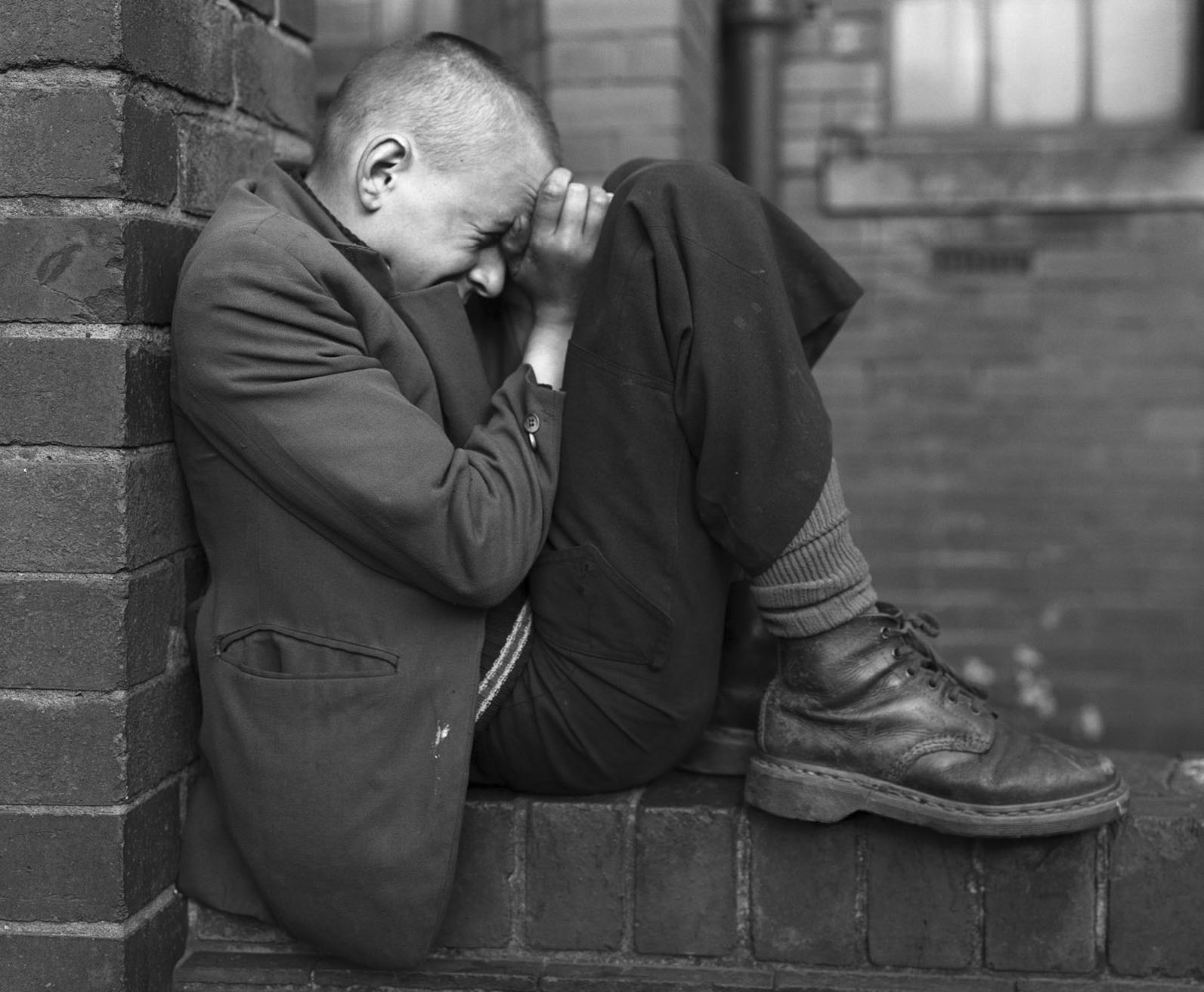

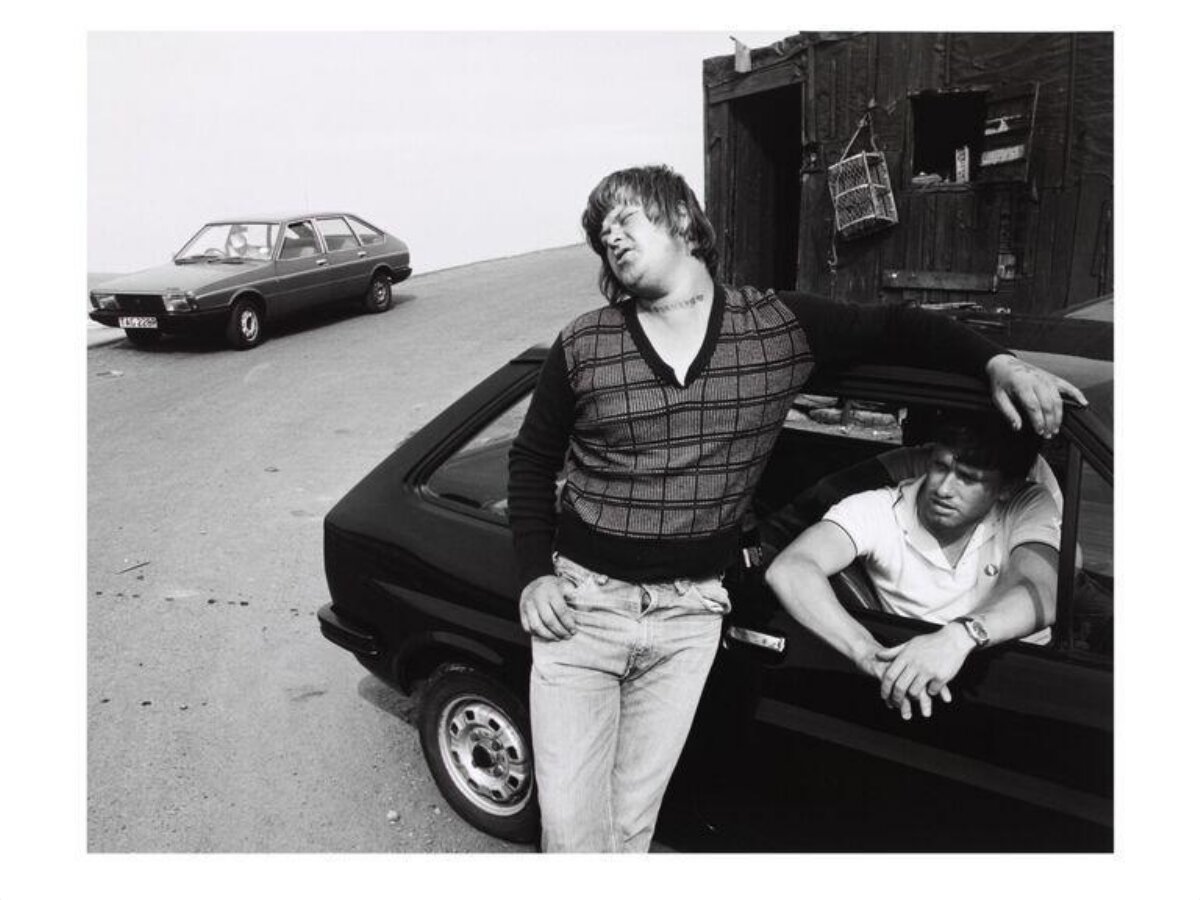

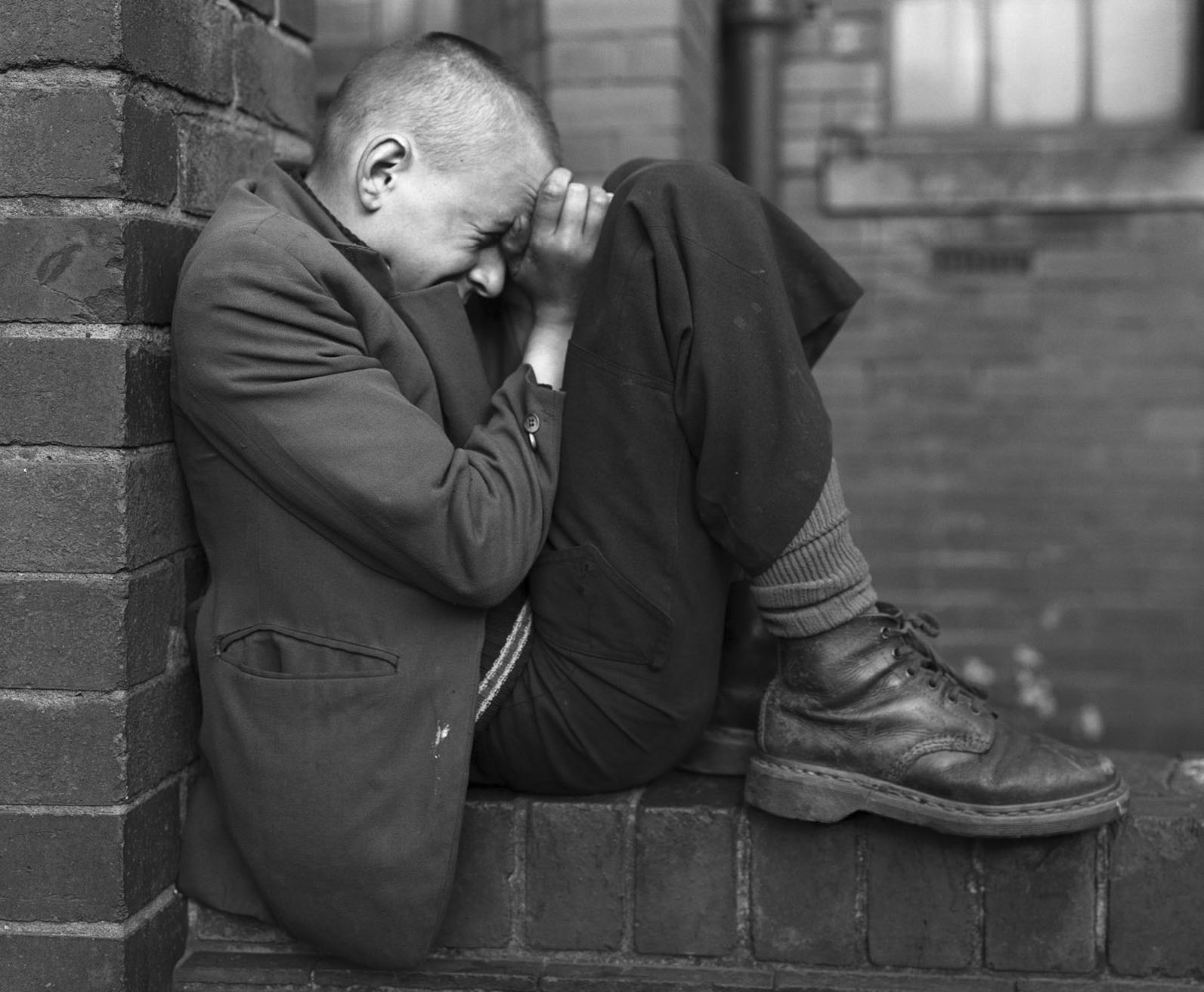

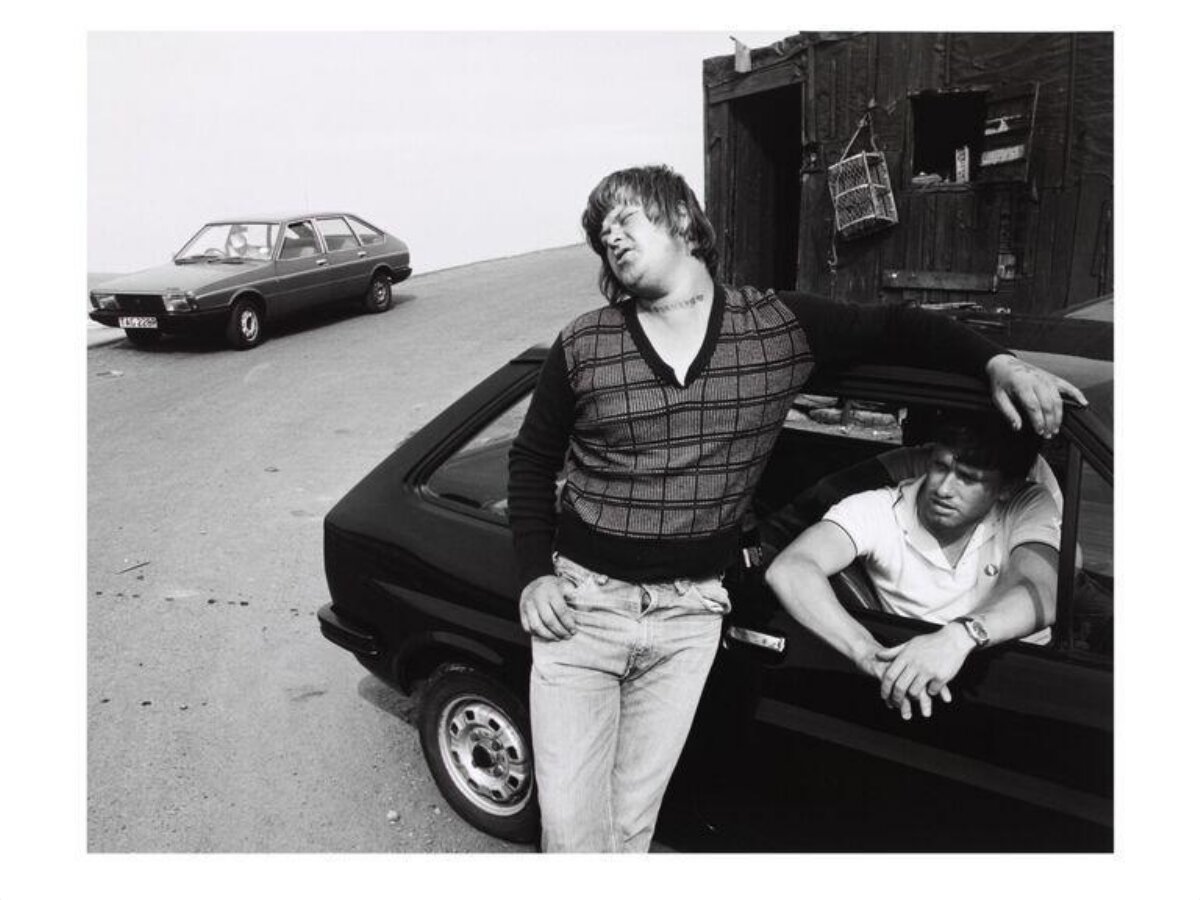

The northeast that Killip encountered was a region in the early stages of catastrophic industrial decline. The shipyards of the Tyne and Wear, the steelworks of Teesside, and the collieries of Durham and Northumberland — the industries that had sustained working-class communities for generations — were closing or contracting, and the social fabric woven around them was beginning to unravel. Killip photographed this world not as a journalist parachuting in for a story but as a participant. He moved to Newcastle, lived among the communities he documented, and spent the better part of fifteen years building a body of work that recorded, with unflinching clarity and deep empathy, the texture of lives lived in the shadow of economic devastation.

His method was painstaking and slow. Working with a large-format 4x5 camera, Killip made images of extraordinary formal power: the silhouette of a shipyard crane against a winter sky, a father and son walking on a bleak beach, a family gathered in a cramped kitchen, the skeletal remains of an industrial landscape. But these were never merely formal exercises. Killip's deep engagement with his subjects — earned through years of sustained presence — gave his photographs an emotional weight and moral authority that no casual visitor could achieve. He understood that the people he was photographing were not victims to be pitied but human beings enduring profound structural injustice with courage, humour, and resilience.

The centrepiece of Killip's career is In Flagrante, published in 1988 by Secker & Warburg. The title, drawn from the legal Latin phrase in flagrante delicto — caught in the act — was deliberately provocative: it implied that the photograph was catching not its subjects but society itself in the act of committing a crime against its own people. The book presented a sequence of images from Tyneside and the northeast spanning roughly a decade, from the mid-1970s to the mid-1980s, and it was received as a masterpiece. In Flagrante is now widely regarded as one of the most important photobooks of the twentieth century, standing alongside Robert Frank's The Americans and Walker Evans's American Photographs in the canon of documentary photography.

Killip's other major body of work focused on the seacoal communities of Lynemouth, on the Northumberland coast, where families collected coal that washed up on the beach from undersea seams and offshore dumping by the National Coal Board. These were among the poorest and most marginalised people in England, living in caravans and makeshift shelters on a windswept coastline, and Killip photographed them over several years with a tenderness and respect that never tipped into condescension. The seacoal pictures, particularly the iconic image of a horse and its rider returning from the beach, are among the most powerful photographs in the British documentary tradition.

In 1991, Killip moved to the United States, accepting a professorship at Harvard University, where he taught in the Visual and Environmental Studies department until his retirement. The move was, in some ways, an exile: Killip had given so much of himself to the northeast of England that the transition to the manicured campus of Harvard represented a wrenching dislocation. He continued to photograph, producing work on the Isle of Man, on Pirelli factory workers, and on other subjects, but the northeast work remained the towering achievement of his career. Chris Killip died in 2020 in Cambridge, Massachusetts. His legacy is that of a photographer who understood that documentary photography is not merely a way of recording the world but a way of bearing witness to it — and that bearing witness, done with sufficient commitment and skill, becomes an act of conscience.

I wanted to photograph a world that was being systematically destroyed, and I wanted those photographs to have some permanence against the forces that were destroying it. Chris Killip

The landmark photobook documenting industrial decline in northeast England across a decade, whose title accused society of being caught in the act of a crime against its own working-class communities. Widely regarded as one of the great photobooks of the twentieth century.

A sustained study of the seacoal-gathering communities on the Northumberland coast, photographing families who collected washed-up coal from the beach in some of the harshest conditions in England, with tenderness and monumental compositional power.

A return to Killip's birthplace, expanding on his original 1969 Arts Council commission with new and previously unseen images that traced the island's transformation across half a century.

Born in Douglas, Isle of Man. Leaves school at sixteen and discovers photography through a library copy of Cartier-Bresson's The Decisive Moment.

Moves to London to work as a photographic assistant, spending free time studying collections at the Victoria and Albert Museum.

Receives an Arts Council commission to photograph the Isle of Man, producing his first significant body of work.

Moves to Newcastle upon Tyne and begins documenting the industrial communities of northeast England with a large-format camera.

Spends a decade photographing Tyneside, the Durham coalfields, and the seacoal communities of Lynemouth, building relationships over years of sustained engagement.

In Flagrante published by Secker & Warburg, establishing Killip as one of the most important documentary photographers of his generation.

Moves to the United States to accept a professorship at Harvard University, teaching in the Visual and Environmental Studies department.

Major retrospective at Museum Folkwang in Essen, Germany, and Le Bal in Paris, reaffirming the significance of his northeast England work.

Dies in Cambridge, Massachusetts. His legacy as the foremost photographer of British industrial decline endures through In Flagrante and his broader body of work.

Interested in discussing photography, collaboration, or just want to say hello? I’d love to hear from you.

Contact →