Britain's most influential photographer of the twentieth century, whose stark, dramatic images moved from unflinching social documentary of class-divided England through the blackout poetry of wartime London to the distorted, surreal nudes that redefined the photographic body.

1904, Hamburg, Germany – 1983, London, England — British

Bill Brandt was born Hermann Wilhelm Brandt on 3 May 1904 in Hamburg, Germany, into a prosperous family with British connections. His early life was marked by illness; he contracted tuberculosis as a young man and spent several years in a Swiss sanatorium, an experience of enforced solitude and observation that may have shaped his intensely visual sensibility. After his recovery, he moved to Vienna, where he briefly underwent psychoanalysis — an encounter with the Freudian unconscious that would leave traces throughout his later work, particularly in the dreamlike quality of his nude studies. In 1929, Brandt went to Paris, where he worked for several months as an assistant in the studio of Man Ray, absorbing the Surrealist fascination with the strange, the uncanny, and the transformation of the ordinary into the extraordinary.

In 1934, Brandt settled permanently in London and reinvented himself as an English photographer, gradually obscuring his German origins — a biographical reticence that he maintained for the rest of his life. His first major body of work was a social documentary project that examined the stark divisions of the English class system with a foreigner's astonished eye. Published in 1936 as The English at Home, the book juxtaposed images of wealth and poverty with a coolness that was more devastating than any polemic: parlourmaids standing at attention beside their mistresses, coal miners returning from the pit, families in Mayfair drawing rooms and families in northern slums. The companion volume, A Night in London (1938), extended the survey into the nocturnal city, photographing streetwalkers, pub-goers, Billingsgate fishmongers, and the homeless sleeping rough under bridges.

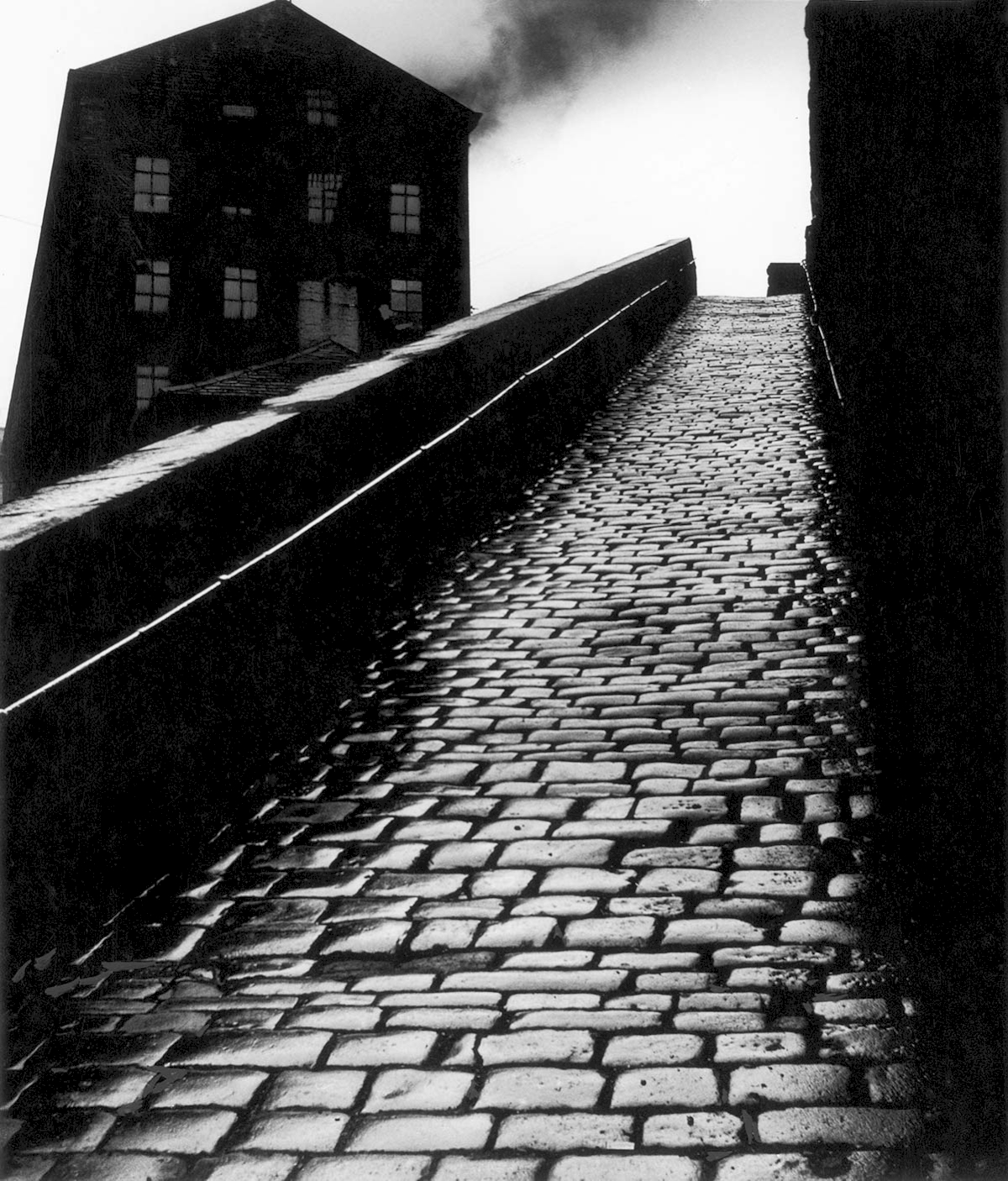

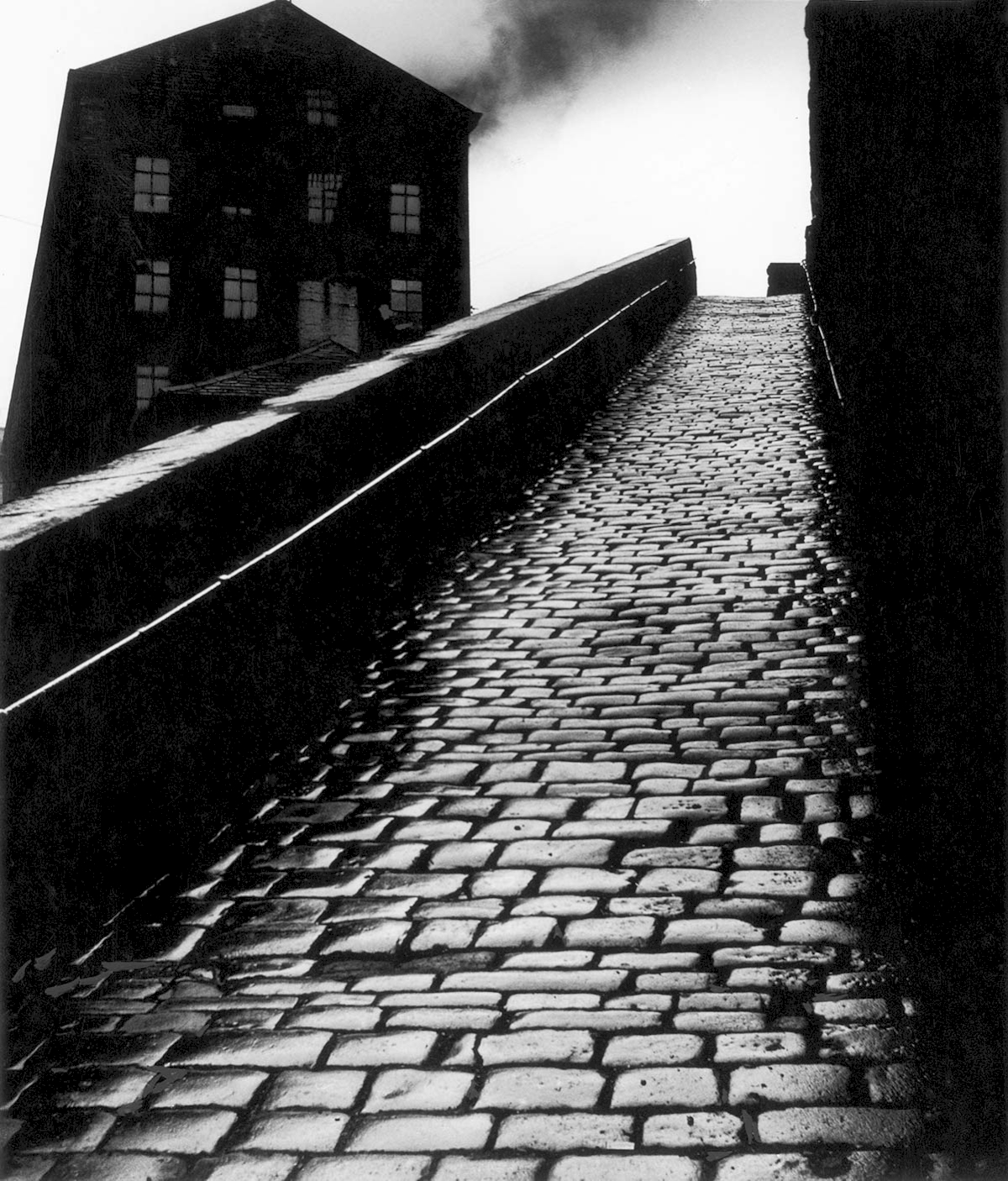

Brandt's social documentary work of the 1930s was notable not merely for its subject matter but for its visual character. His images were printed in deep, dramatic blacks, with a tonal range that emphasised contrast and shadow at the expense of the middle greys that most photographers sought. This graphic intensity gave his photographs a quality that was simultaneously documentary and expressionistic — they recorded the real world, but they transformed it into something more heightened, more theatrical, more emotionally charged than conventional reportage. Brandt's England was not a neutral country observed; it was a landscape of extremes, of light and darkness, wealth and poverty, intimacy and isolation.

During the Second World War, Brandt produced some of the most memorable images of the London Blitz. Working for the Ministry of Information and for magazines including Picture Post and Lilliput, he photographed Londoners sheltering in Underground stations and in the crypts of churches, the blacked-out streets of the capital, and the eerie, depopulated cityscapes lit by searchlights and fire. His image of St Paul's Cathedral rising above the darkened rooftops of the City became one of the iconic photographs of wartime Britain. The blackout, with its elimination of artificial light and its transformation of familiar streets into realms of shadow, was in some sense the perfect subject for Brandt's vision: it turned all of London into the kind of high-contrast, dramatically lit stage that his photographs had always sought to create.

After the war, Brandt embarked on the work that would prove to be his most radical and enduring. In the late 1940s and throughout the 1950s, he produced a series of nude studies using a wide-angle Kodak camera with an extremely short focal length, which distorted the human body into monumental, sculptural forms. Arms and legs swelled to enormous proportions; torsos curved and tapered like Brancusi sculptures; the boundary between flesh and stone, body and landscape, dissolved into ambiguity. These images, collected in Perspective of Nudes (1961), were unlike anything that had been seen before in photography. They drew on Surrealism, on Henry Moore's reclining figures, and on Brandt's own instinct for the uncanny, and they remain among the most original and unsettling nudes in the history of the medium.

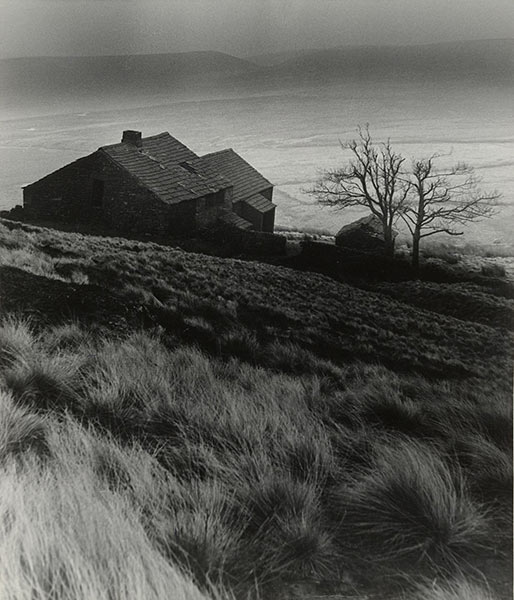

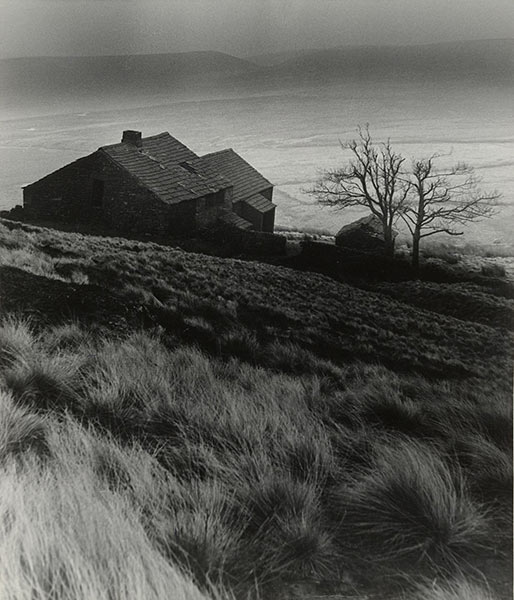

Brandt was also a masterful landscape photographer. His images of the English countryside — the moorlands of Yorkshire, the coastline of Sussex, the ancient stones of the Hebrides — were infused with the same dramatic tonal quality that characterised all his work. He photographed landscapes associated with the great English writers: Top Withens, the ruined farmhouse said to have inspired Wuthering Heights; the Sussex downs of Virginia Woolf; the Dorset coast of Thomas Hardy. These literary landscapes were not mere illustrations; they were photographs that sought to embody the emotional atmosphere of the texts they referenced, and they succeeded to a remarkable degree.

Bill Brandt died on 20 December 1983 in London. His influence on British photography has been immeasurable, and his impact extends far beyond Britain. He demonstrated that photography could move freely between documentary and art, between social observation and personal vision, without compromising either. His dramatic, high-contrast printing style influenced generations of photographers, and his nude studies opened new possibilities for the representation of the body in photography. He remains the towering figure of twentieth-century British photography, and his work continues to astonish with its visual power, its emotional intensity, and its refusal to settle into any single category or mode.

It is part of the photographer's job to see more intensely than most people do. He must have and keep in him something of the receptiveness of the child who looks at the world for the first time. Bill Brandt

A devastating visual survey of the English class system, juxtaposing scenes of wealth and poverty with a cool detachment that exposed the divisions of 1930s Britain more effectively than any written polemic.

A revolutionary series of nude studies made with a wide-angle camera that distorted the human body into monumental, sculptural forms, dissolving the boundaries between flesh, stone, and landscape in images of startling originality.

Images of wartime London during the blackout, capturing Londoners sheltering underground, blacked-out streets, and iconic views of the city's landmarks rising above darkness, combining documentary urgency with poetic intensity.

Born Hermann Wilhelm Brandt in Hamburg, Germany. His youth is marked by illness, including years spent in a Swiss sanatorium recovering from tuberculosis.

Works as an assistant to Man Ray in Paris, absorbing Surrealist ideas about the transformation of reality through the camera.

Settles permanently in London and begins documenting the sharp divisions of the English class system.

Publishes The English at Home, his first major book, revealing the stark contrasts between wealth and poverty in Depression-era Britain.

Begins photographing the London Blitz for the Ministry of Information and magazines, producing some of the most iconic images of wartime Britain.

Photographs the literary landscapes of England — the Yorkshire moors, the Sussex downs, the Dorset coast — for Lilliput and Picture Post.

Begins his revolutionary nude studies using a wide-angle Kodak camera, producing images of radical distortion and sculptural power.

Publishes Perspective of Nudes, the book that establishes his nude studies as a landmark in the history of photographic art.

Dies on 20 December in London. His legacy as the most important British photographer of the twentieth century is firmly established.

Interested in discussing photography, collaboration, or just want to say hello? I’d love to hear from you.

Contact →