The visionary documentarian who captured the dramatic transformation of New York City in the 1930s, preserving the work of Eugène Atget and championing photography as a medium uniquely suited to recording the forces of modernity reshaping the American metropolis.

1898, Springfield, Ohio – 1991, Monson, Maine — American

Berenice Abbott was born on 17 July 1898 in Springfield, Ohio, and grew up in circumstances that were anything but auspicious for a future artist. Her parents separated when she was young, and she was raised in difficult conditions. Fiercely independent from an early age, she left Ohio as soon as she was able, moving first to Columbus, where she briefly attended Ohio State University, and then to New York City in 1918. She arrived in Greenwich Village at a moment when it was the centre of American bohemian life, and she immersed herself in the intellectual and artistic ferment of the neighbourhood, studying sculpture and drawing while supporting herself with odd jobs. In 1921, seeking the wider horizons that so many young American artists craved, she sailed for Europe.

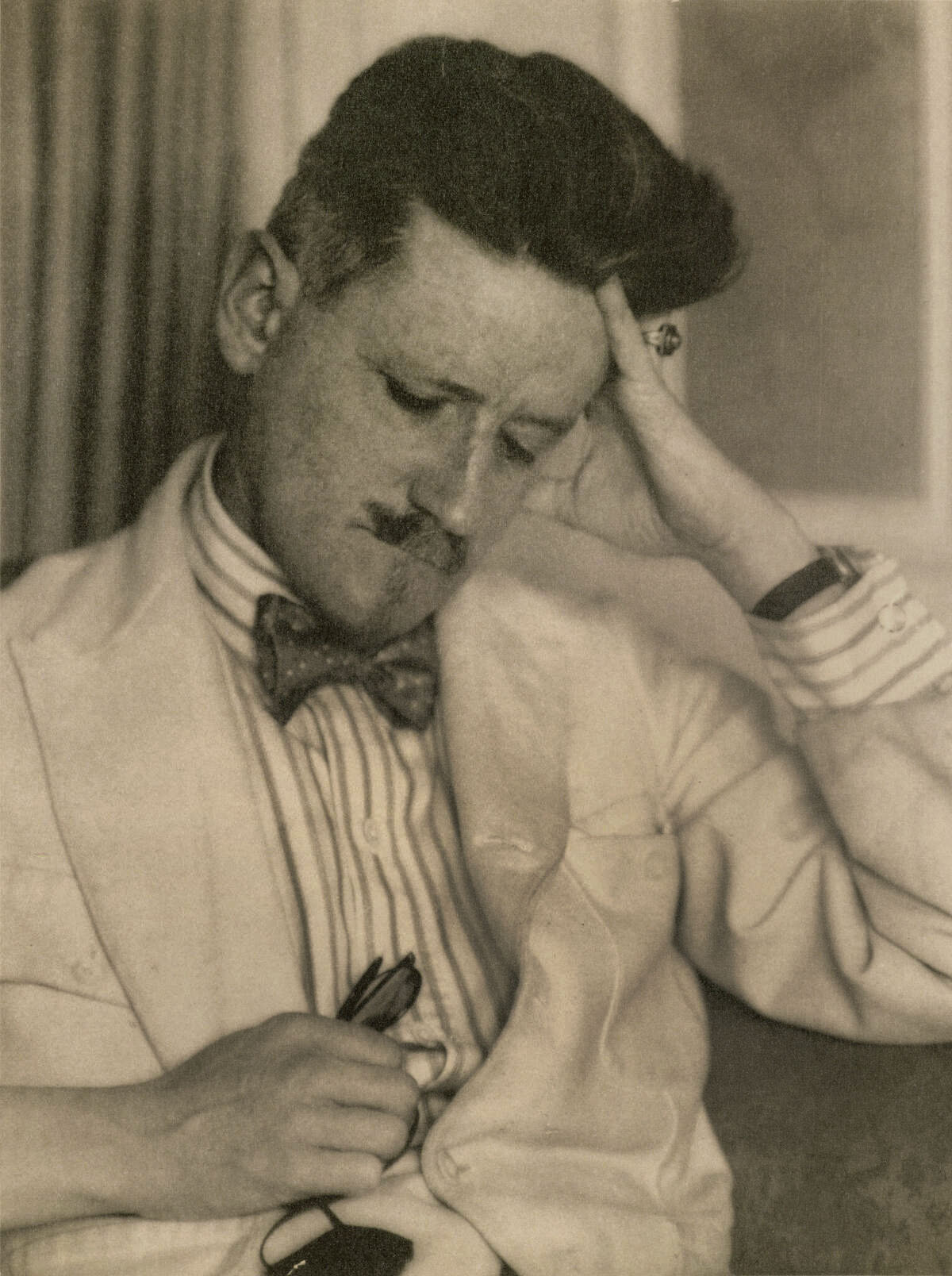

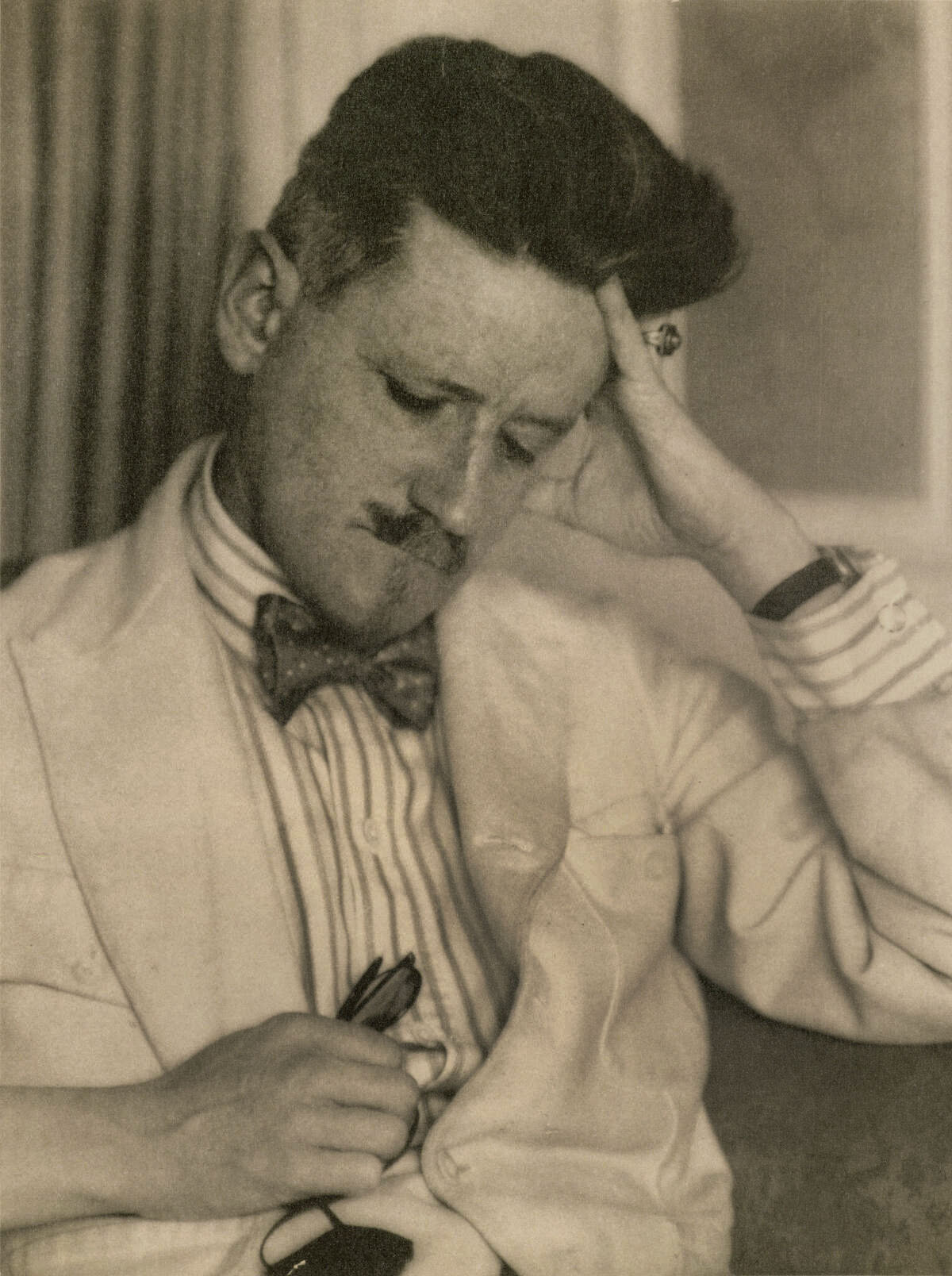

Abbott settled in Paris, where she studied sculpture under Emile Bourdelle and Constantin Brancusi. In 1923, she took a job as a darkroom assistant to the photographer Man Ray, the Dadaist and Surrealist who was then at the height of his fame as a portraitist of the Parisian avant-garde. Working for Man Ray, Abbott learned the craft of photography from one of its most inventive practitioners, and she soon began to make portraits of her own. Her subjects included many of the leading figures of Parisian cultural life — James Joyce, Jean Cocteau, André Gide, Djuna Barnes, and Peggy Guggenheim, among others — and her portraits were distinguished by a directness and psychological clarity that stood apart from Man Ray's more theatrical approach.

It was during her time in Paris that Abbott made the discovery that would change the course of her career. In 1925, she visited the studio of Eugène Atget, the elderly French photographer who had spent thirty years documenting the streets, shopfronts, parks, and architectural details of Paris with a methodical devotion that had produced one of the most extraordinary bodies of work in the history of the medium. Atget was then virtually unknown, and his thousands of glass-plate negatives were at risk of being lost. Abbott was overwhelmed by what she saw. She recognised in Atget's work a quality of seeing that transcended mere documentation — a poet's feeling for the texture of the city combined with a scientist's precision of record. After Atget's death in 1927, Abbott purchased his archive of negatives and prints, and she spent the rest of her life promoting his work, eventually securing his recognition as one of the most important photographers who ever lived.

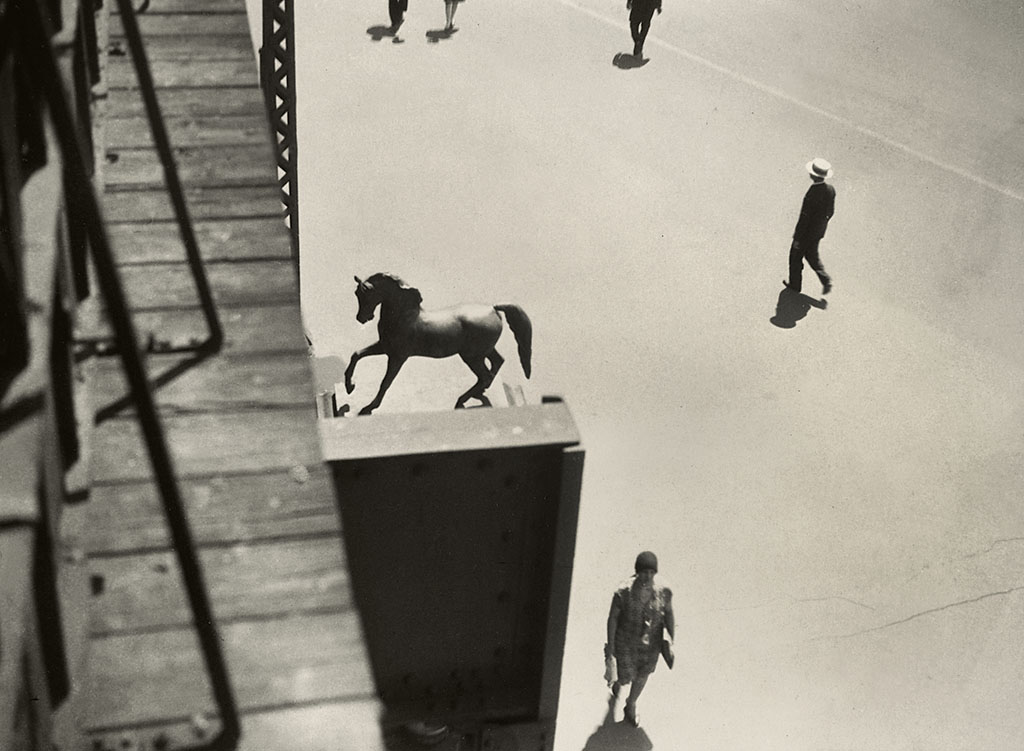

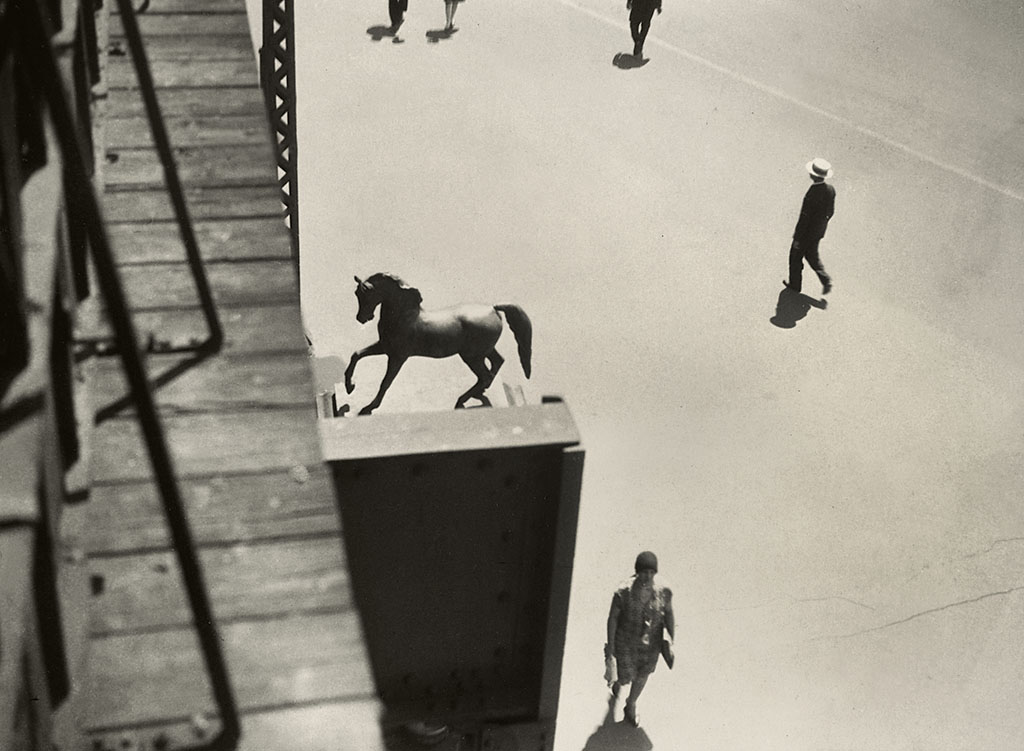

In 1929, Abbott returned to New York and was astonished by the transformation of the city she had left eight years earlier. Manhattan was in the grip of a building boom of unprecedented scale; the skyline was changing daily as new skyscrapers rose from the streets of Midtown and the Financial District. Abbott saw in this upheaval the subject for a photographic project of Atget-like ambition: a systematic documentation of New York City at the moment of its most dramatic metamorphosis. She began photographing the city immediately, working with a large-format camera and producing images of extraordinary architectural clarity and compositional power.

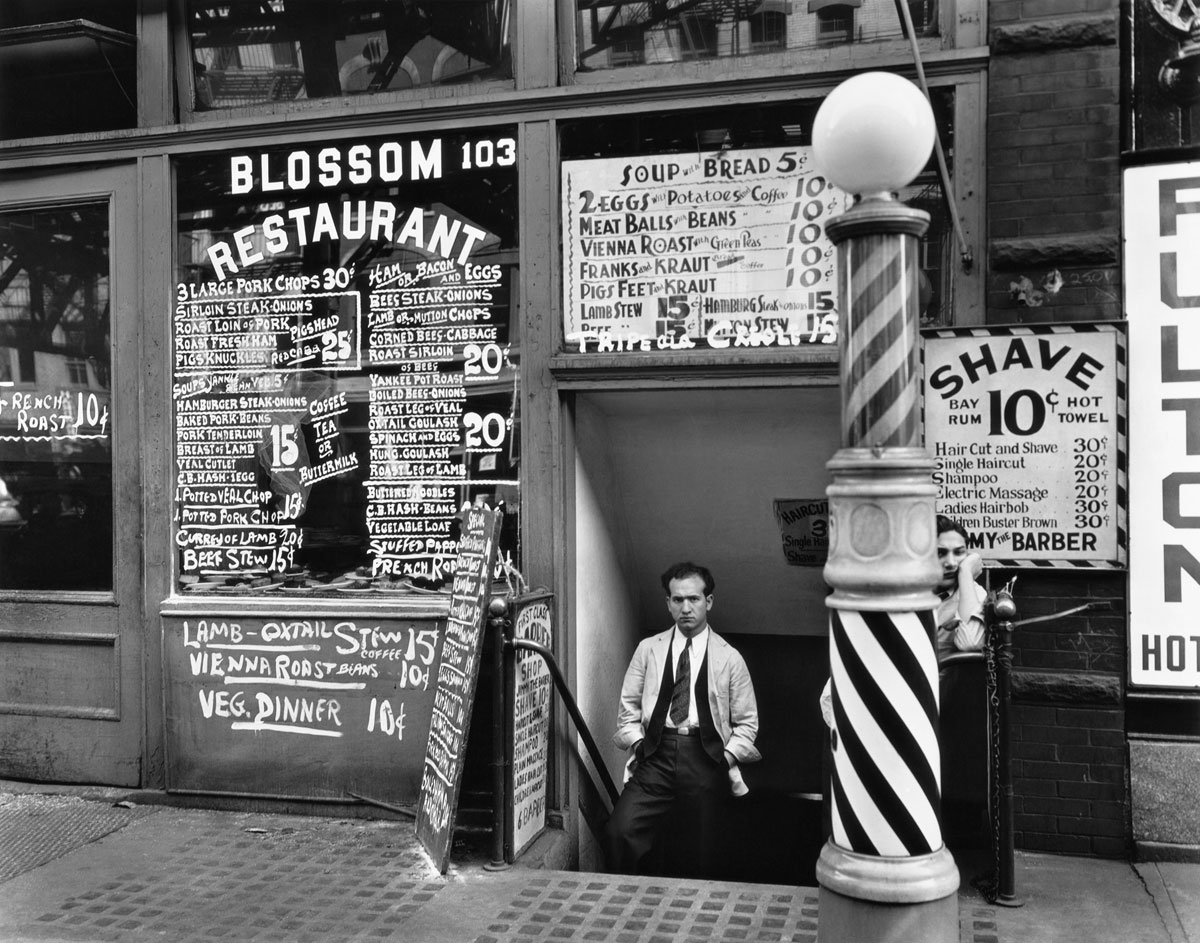

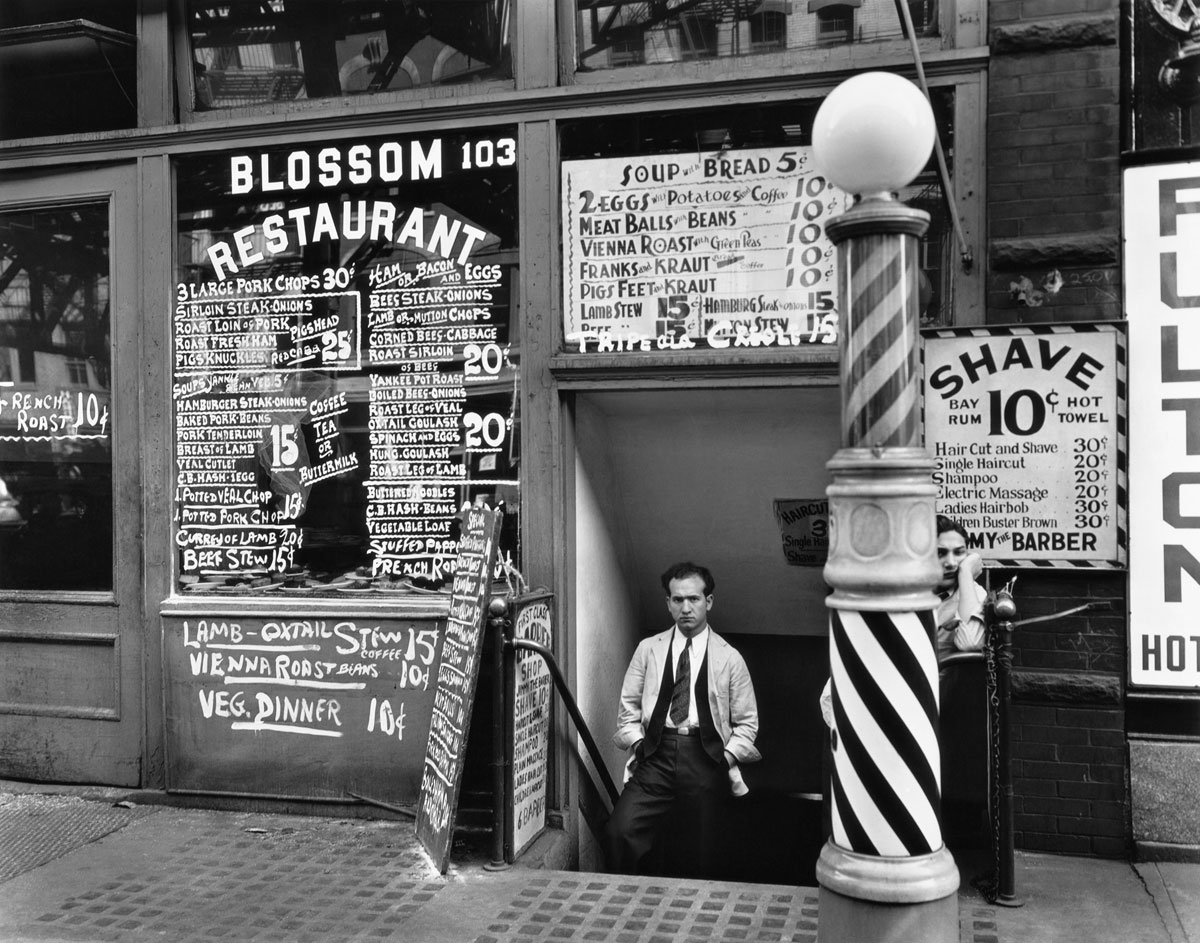

For several years Abbott financed the project herself, but in 1935 she secured funding from the Federal Art Project, the visual arts arm of the New Deal's Works Progress Administration. With this support, she was able to devote herself fully to the work, and between 1935 and 1939 she produced the images that would be published in 1939 as Changing New York, with text by the art critic Elizabeth McCausland. The book is one of the great achievements of American photography: a portrait of a city in the process of remaking itself, in which the old and the new, the monumental and the humble, the vertical thrust of the skyscrapers and the horizontal sprawl of the streets exist in a state of dynamic tension. Abbott photographed with equal attention the soaring canyons of Wall Street and the cluttered storefronts of the Lower East Side, the engineering marvels of the new bridges and the decrepit tenements about to be demolished.

After completing Changing New York, Abbott turned her attention to a subject that might seem remote from urban documentation: scientific photography. She had long believed that photography was the ideal medium for making scientific principles visible, and in the 1940s and 1950s she produced a body of work illustrating the laws of physics — magnetism, motion, light, and wave behaviour — with images of striking visual clarity. This work was published in several textbooks and used widely in science education. Abbott's scientific photographs demonstrated the same qualities that had defined her urban work: precision, clarity, respect for the subject, and an unwillingness to sacrifice accuracy for aesthetic effect.

In 1966, Abbott sold the Atget archive to the Museum of Modern Art, securing its permanent preservation and ensuring that Atget's work would be accessible to scholars and the public. She retired to Monson, Maine, a small town in the rural interior of the state, where she spent the last twenty-five years of her life. She continued to photograph and to write about photography, and she remained a fierce advocate for the documentary tradition and for the idea that photography's greatest strength lay in its capacity to record the real world with fidelity and clarity. Berenice Abbott died on 9 December 1991, at the age of ninety-three. Her legacy encompasses not only her own extraordinary images but the preservation and promotion of Atget's work, and a philosophical commitment to photography as an art of seeing that remains as vital and as relevant as ever.

Photography can never grow up if it imitates some other medium. It has to walk alone; it has to be itself. Berenice Abbott

A monumental photographic survey of New York City during the Depression era, documenting the collision of old and new as the city transformed itself through demolition and construction on an unprecedented scale. Published as a book in 1939 with text by Elizabeth McCausland.

A series of penetrating portraits of the leading figures of Parisian cultural life, including James Joyce, Jean Cocteau, and Djuna Barnes, made during Abbott's years in the French capital and characterised by a directness that cut through artistic pretension.

A body of work illustrating the principles of physics through photography, demonstrating magnetism, wave behaviour, and motion with images of remarkable visual clarity that were widely used in science education.

Born on 17 July in Springfield, Ohio. Grows up in difficult family circumstances that foster a fierce independence.

Sails to Europe, settling in Paris, where she studies sculpture and begins to move in avant-garde circles.

Becomes darkroom assistant to Man Ray in Paris, learning the craft of photography and beginning to make her own portraits of cultural figures.

Discovers the work of Eugène Atget in his Paris studio, an encounter that profoundly shapes her understanding of photography's documentary potential.

Returns to New York and is struck by the city's rapid transformation. Begins photographing the urban landscape with a large-format camera.

Secures funding from the Federal Art Project to pursue her documentation of New York City full-time.

Publishes Changing New York with text by Elizabeth McCausland, establishing the definitive photographic portrait of the city during the Depression era.

Publishes scientific photography in educational textbooks, demonstrating her belief that photography is the ideal medium for making scientific principles visible.

Sells the Eugène Atget archive to the Museum of Modern Art, securing the permanent preservation of one of photography's most important bodies of work.

Dies on 9 December in Monson, Maine, at the age of ninety-three, having devoted her life to the documentary power of photography and the preservation of its history.

Interested in discussing photography, collaboration, or just want to say hello? I’d love to hear from you.

Contact →