The systematic portraitist of an entire civilisation, whose monumental project to classify German society through photographs produced one of the most ambitious and profound bodies of work in the history of the medium.

1876, Herdorf, Germany – 1964, Cologne, Germany — German

August Sander was born in 1876 in Herdorf, a small mining town in the Siegerland region of Germany, the son of a mine carpenter who worked the local ore deposits. The boy grew up in a landscape shaped by heavy industry and rural tradition, and his earliest understanding of the world was formed by the rigid social hierarchies of the Wilhelmine era — the farmer, the miner, the foreman, the merchant — categories of people defined by their labour and their place in a community. It was while working as a young labourer in the mines that Sander first encountered photography, assisting a photographer who had been commissioned to document the mining operations. The experience was transformative. He recognised in the camera an instrument capable of recording not merely appearances but social identities, and he resolved to pursue the medium seriously.

Sander studied at the Kunstakademie in Dresden, where he received a formal training in the pictorial and technical aspects of photography that was then considered essential for professional practice. After completing his studies, he opened a commercial portrait studio in Linz, Austria, in 1901, building a successful business photographing the families, tradesmen, and civic figures of the region. His early portraits were competent and conventional, made in the soft-focus pictorialist style fashionable at the time. But even in these commissioned works, there were signs of the rigorous, classificatory intelligence that would later distinguish his great project: an attention to posture, clothing, tools, and setting as markers of social position, and a preference for directness over flattery.

In 1910, Sander returned to Germany and established a new studio in Cologne, the city that would remain his base for the rest of his life. It was during this period that he began to conceive the extraordinary ambition that would define his career: a systematic photographic survey of German society, organised not by region or chronology but by social type. He would photograph the farmer, the craftsman, the artist, the professional, the industrial worker, the soldier, the beggar — every stratum of a complex civilisation — and arrange them into a comprehensive atlas of the nation. The project, which he eventually titled People of the Twentieth Century, would occupy him for the next four decades and produce one of the most remarkable bodies of work in the history of photography.

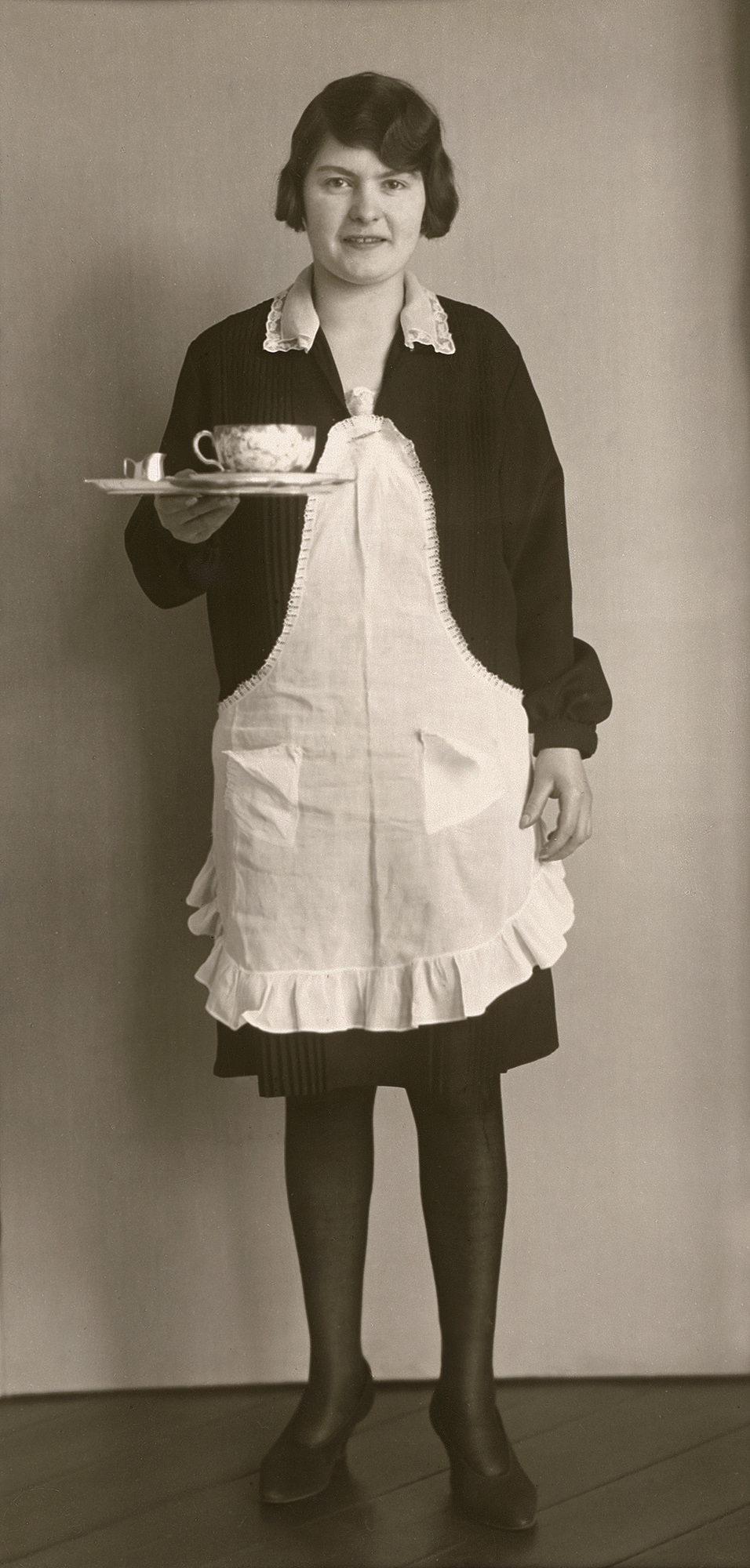

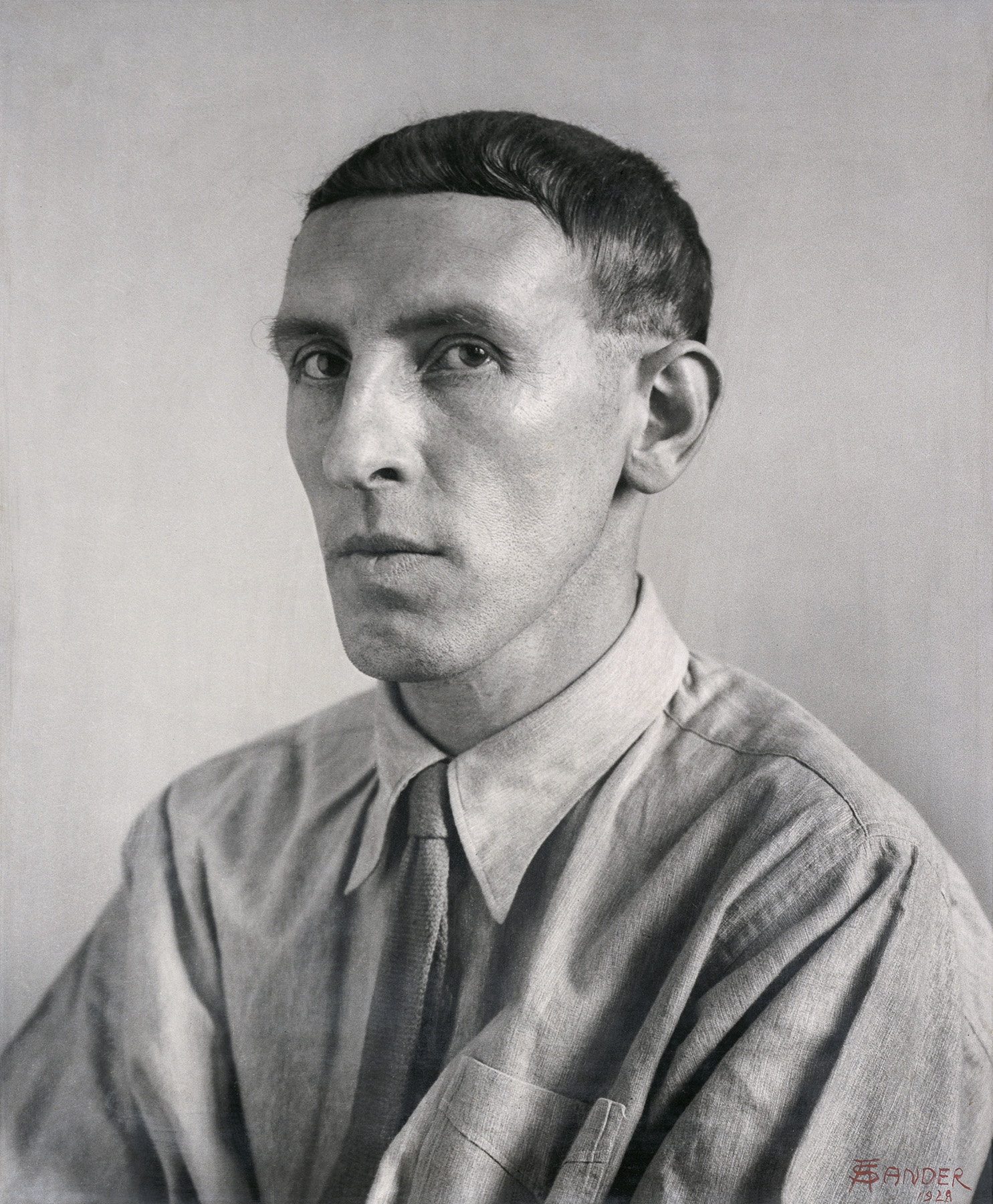

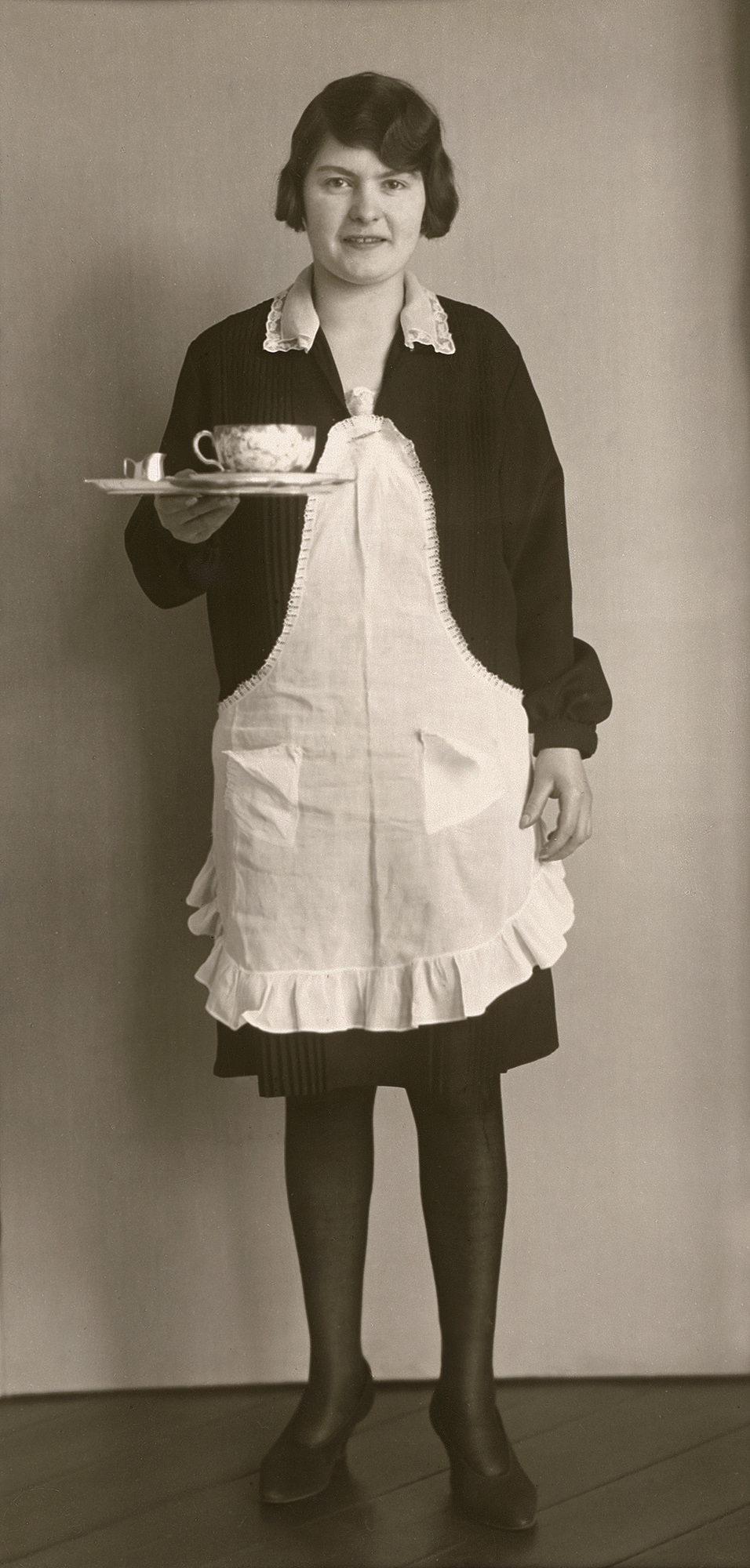

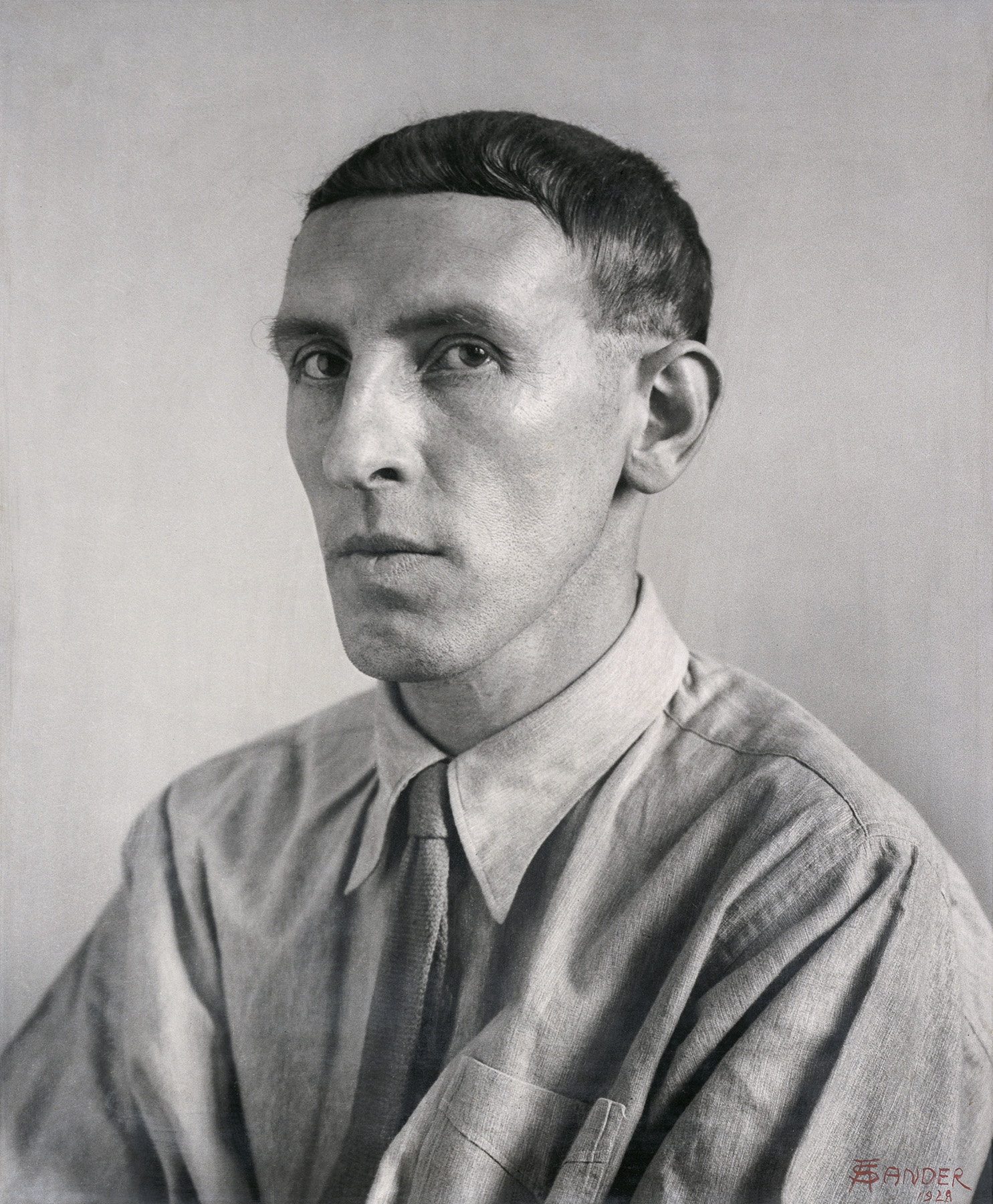

By the mid-1920s, Sander had begun to formalise the structure of People of the Twentieth Century, organising his portraits into seven major groups — The Farmer, The Skilled Tradesman, The Woman, Classes and Professions, The Artists, The City, and The Last People — comprising forty-five individual portfolios. Each group was intended to represent a fundamental aspect of the social order, and within each group the portraits moved from the specific to the general, from the individual face to the archetype. Sander photographed his subjects with a large-format camera, almost always in their own environments — the farmer in his field, the bricklayer at his wall, the pastry cook in his kitchen — using natural light and a direct, frontal composition that afforded each person the same measured dignity regardless of their station.

In 1929, Sander published Antlitz der Zeit (Face of Our Time), a selection of sixty portraits drawn from the larger project, with an introduction by the novelist Alfred Döblin. The book was a critical success, praised for the clarity and democratic spirit of its vision. But the political landscape was shifting violently. When the Nazis came to power in 1933, Sander's inclusive, typological approach to German society — which treated every class and condition with the same unsentimental respect — was incompatible with the regime's racial ideology and its insistence on a single, mythologised national identity. In 1936, the Nazis seized and destroyed the printing plates of Face of Our Time, effectively suppressing the book. Sander's son Erich, a member of the left-wing resistance, was arrested by the Gestapo and imprisoned; he died in custody in 1944, a devastating personal blow from which Sander never fully recovered.

The war brought further catastrophe. In 1944, Allied bombing destroyed Sander's Cologne studio along with an estimated thirty thousand negatives — an incalculable loss to the archive he had spent decades assembling. Sander had managed to evacuate a portion of his work to the countryside, and it was these surviving negatives and prints that preserved the core of People of the Twentieth Century for posterity. In the devastated post-war landscape, the ageing photographer continued to work, adding new portraits to the project and documenting the shattered cities and displaced populations of a Germany that bore little resemblance to the ordered society he had set out to catalogue decades earlier.

Sander died in Cologne in 1964, at the age of eighty-seven, without having completed People of the Twentieth Century in its intended form. The full project was published posthumously, edited by his son Gunther Sander in collaboration with scholars and curators who recognised the monumental significance of the work. In the decades since his death, Sander has come to be regarded as one of the most important photographers of the twentieth century — a figure whose influence extends far beyond the documentary tradition into the realms of conceptual art, sociology, and visual culture.

His impact on subsequent generations has been profound. Bernd and Hilla Becher, who studied Sander's methods closely, adapted his typological approach to the documentation of industrial architecture, producing their own systematic catalogues of water towers, blast furnaces, and winding towers that became foundational works of the Düsseldorf School. Through the Bechers, Sander's influence passed to photographers such as Thomas Struth, Thomas Ruff, and Andreas Gursky, whose monumental, rigorously structured images owe a direct debt to the classificatory vision Sander pioneered. His legacy endures as a reminder that photography, at its most ambitious, can aspire to nothing less than a portrait of an entire civilisation — and that the plainest, most democratic form of looking can produce art of the highest order.

The individual does not make the history of his time, he both impresses himself on it and expresses its meaning. August Sander

Sander's lifelong masterwork: a systematic photographic atlas of German society organised into seven groups and forty-five portfolios, aspiring to nothing less than a complete portrait of a civilisation through its representative types.

The first published selection from People of the Twentieth Century, containing sixty portraits that offered an unflinching cross-section of Weimar-era Germany before the Nazis suppressed the project.

A parallel body of work documenting the cities, villages, and industrial terrain of the Rhineland, extending Sander's encyclopaedic vision from the human subject to the built and natural environment.

Born in Herdorf, Germany, the son of a mine carpenter. Discovers photography while working in the local mines.

Studies at the Kunstakademie in Dresden. Opens a commercial portrait studio in Linz, Austria.

Returns to Cologne and establishes a new studio, beginning to conceive the systematic photographic survey of German society that will become his life's work.

Photographs Young Farmers on Their Way to a Dance, one of his earliest and most celebrated images.

Begins formally organising People of the Twentieth Century, a monumental project to classify German society through portraiture.

Publishes Antlitz der Zeit (Face of Our Time), the first selection from the project, to critical acclaim.

The Nazi regime seizes and destroys the printing plates of Face of Our Time. His son Erich, a member of the resistance, is arrested and will later die in custody.

Allied bombing destroys his Cologne studio and an estimated 30,000 negatives. Sander evacuates surviving work to the countryside.

Continues photographing for People of the Twentieth Century in the devastated post-war landscape, though the project will never be completed.

Dies in Cologne at the age of eighty-seven. His influence on conceptual photography, typological practice, and the work of Bernd and Hilla Becher endures as one of the most significant in the medium's history.

Interested in discussing photography, collaboration, or just want to say hello? I’d love to hear from you.

Contact →