The father of environmental portraiture, whose innovative approach of photographing subjects within the context of their work and surroundings produced some of the most iconic and psychologically penetrating portraits of the twentieth century's greatest artists, musicians, politicians, and industrialists.

1918, New York City – 2006, New York City — American

Arnold Newman was born on 3 March 1918 in New York City, though he grew up in Atlantic City, New Jersey, and later in Miami Beach, Florida. His family's circumstances were modest; his father managed a series of small businesses, and the young Newman showed an early aptitude for drawing and painting. He won a scholarship to study art at the University of Miami in 1936, but financial hardship forced him to leave after two years. Unable to continue his formal education, he took a job at a chain portrait studio in Philadelphia, operating a camera for the first time in a commercial context. It was unglamorous work — assembly-line portraits of couples and families against stock backdrops — but it gave Newman a thorough grounding in the mechanics of portraiture and, perhaps more importantly, an intimate understanding of the conventions he would later reinvent.

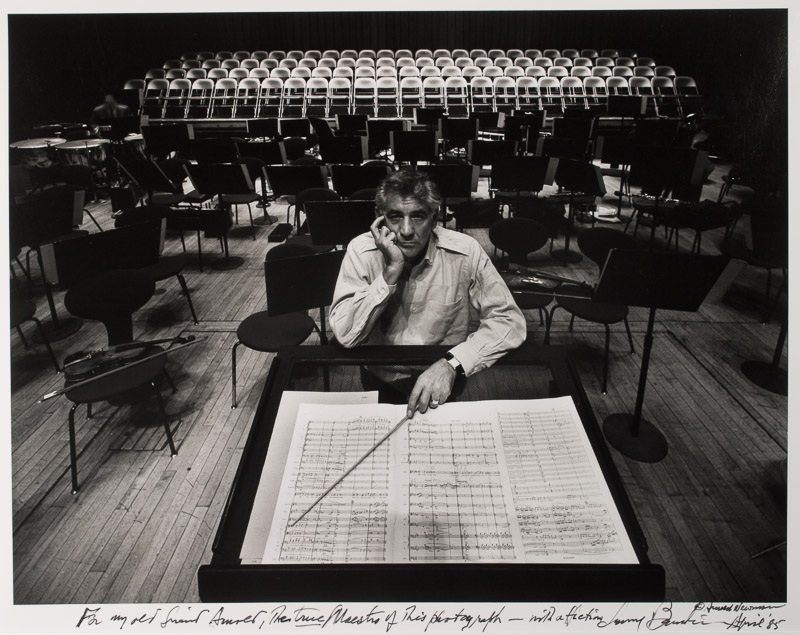

In 1939, Newman moved back to New York and began to pursue photography on his own terms. He haunted the galleries of 57th Street, absorbing the work of the modern painters and sculptors whose innovations were reshaping the art world. He began to photograph artists in their studios — not as an assignment but out of genuine fascination — and in doing so discovered the approach that would define his career. Rather than extracting his subjects from their environments and placing them against neutral backgrounds, as studio portraitists traditionally did, Newman placed them within the spaces where they lived and worked, using the tools, objects, and architecture of their creative lives as compositional elements that revealed character, vocation, and inner life. He called this approach environmental portraiture, and it represented a fundamental rethinking of what a portrait could be.

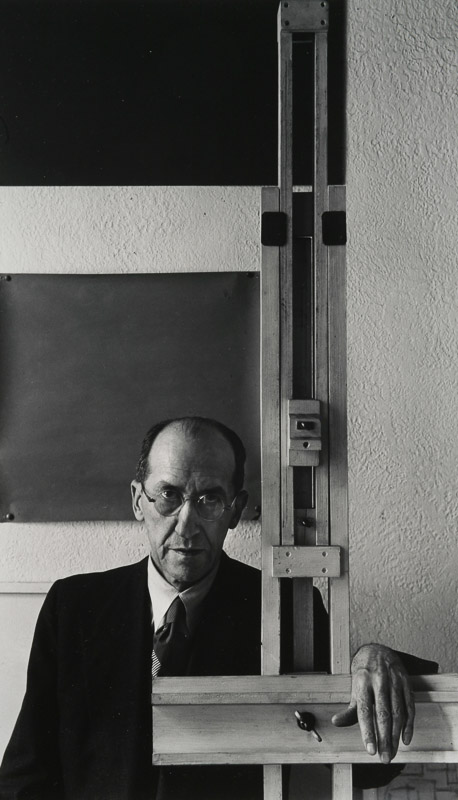

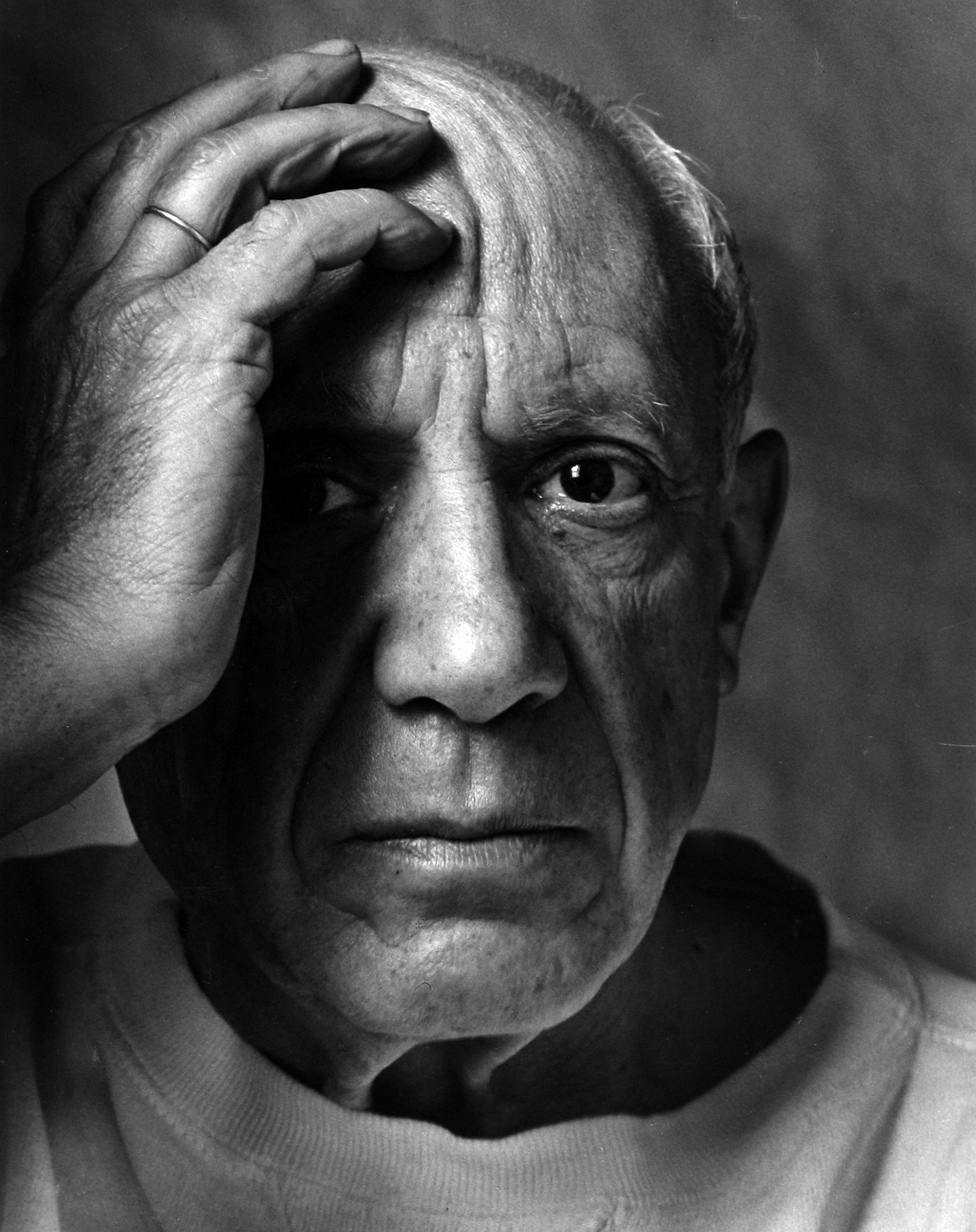

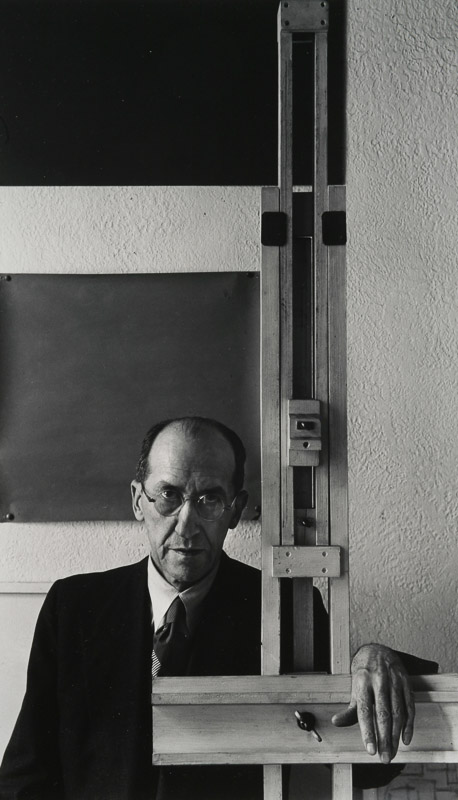

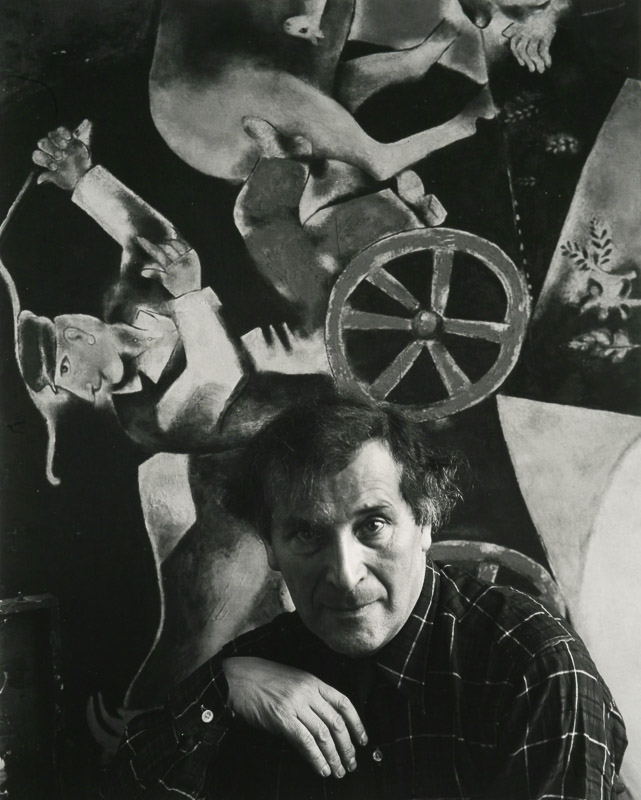

The breakthrough came in 1941, when Newman's work was shown at the A.D. Gallery in New York alongside photographs by Ben Rose. The exhibition attracted the attention of Beaumont Newhall, the curator of photography at the Museum of Modern Art, and Alfred Stieglitz, whose endorsement carried enormous weight. Newman was suddenly recognised as a significant new voice in American photography, and commissions began to follow. Over the next decade he photographed a remarkable gallery of subjects: Piet Mondrian in his austere New York studio in 1942, the geometric patterns of the room echoing the painter's compositions; Max Ernst among his fantastical sculptures; Igor Stravinsky at a grand piano in 1946, the lid of the instrument forming a bold graphic shape that dominated the frame and became one of the most recognisable images in the history of photography.

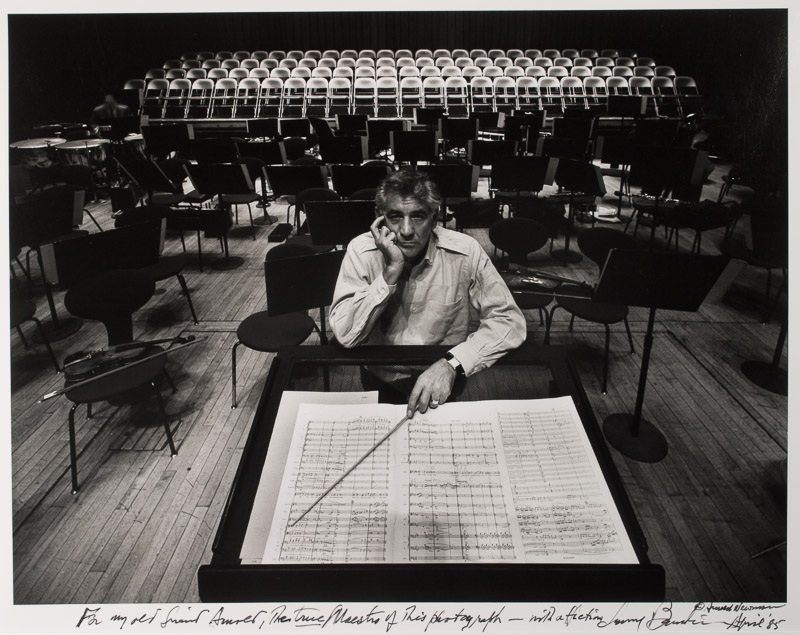

The Stravinsky portrait exemplified Newman's method. The composer was small, compact, reserved — and Newman placed him at the bottom-left corner of the frame, dwarfed by the massive, angular form of the piano lid that swept across the upper portion of the image. The result was simultaneously a portrait, an abstraction, and a visual metaphor for the relationship between the artist and his instrument. Newman understood that a portrait need not show the whole face to reveal the whole person; the environment, the objects, the geometry of the space could do the work that expression alone could not. This insight became the foundation of his entire practice and influenced generations of portrait photographers who followed.

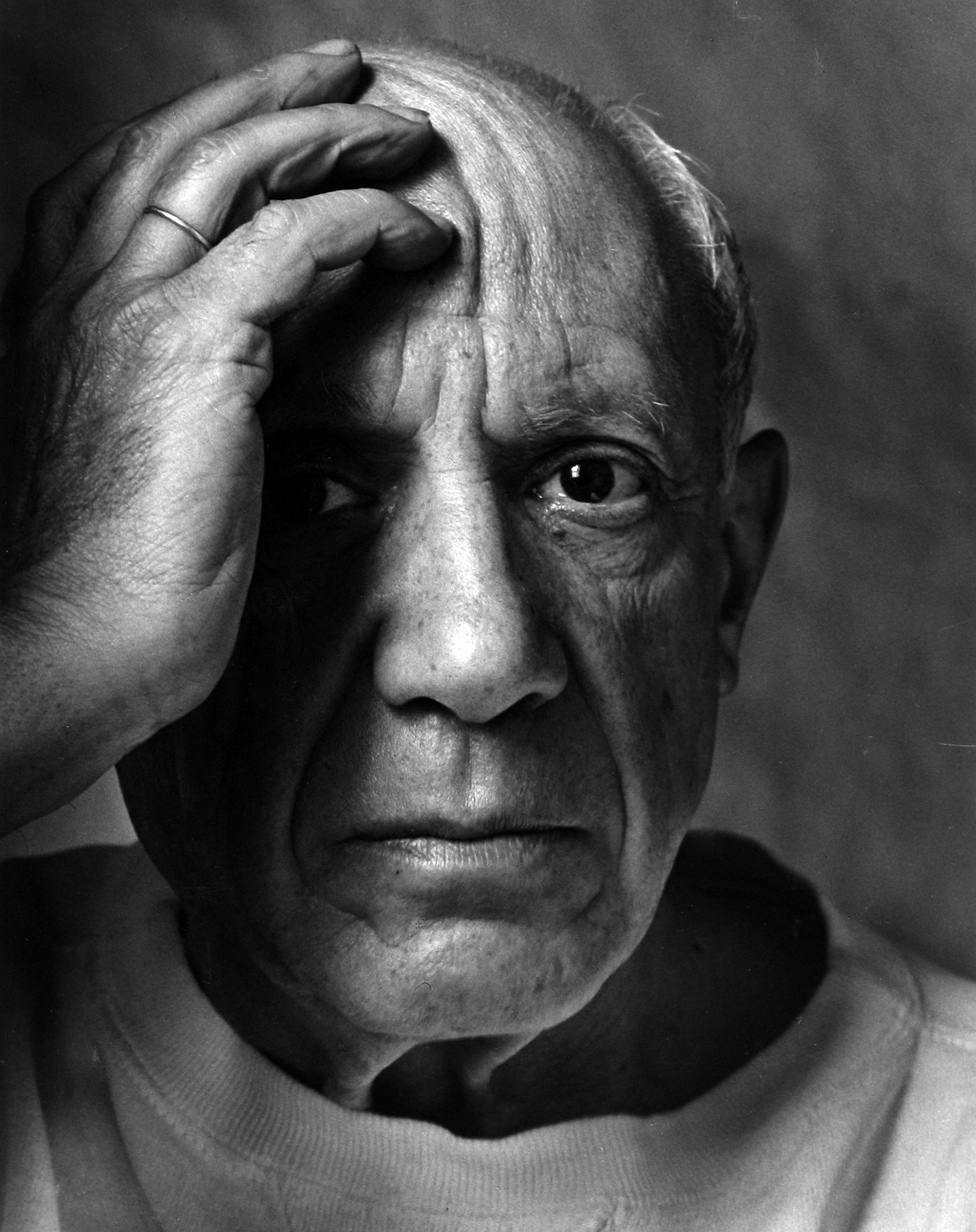

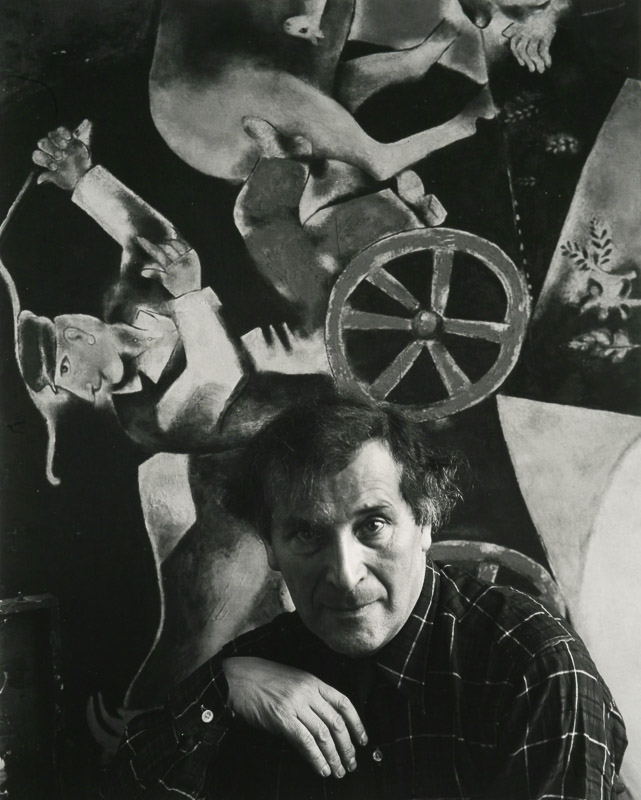

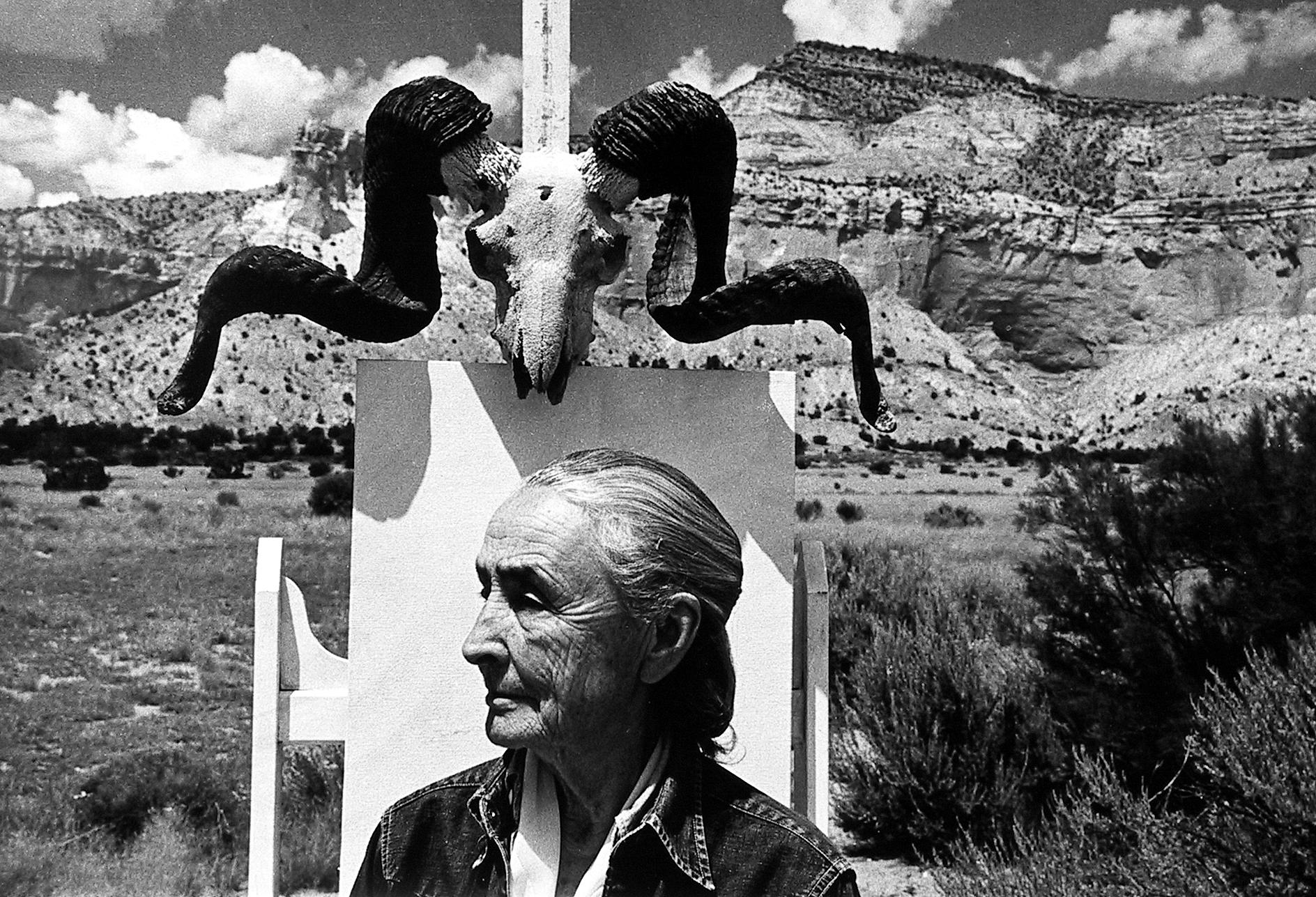

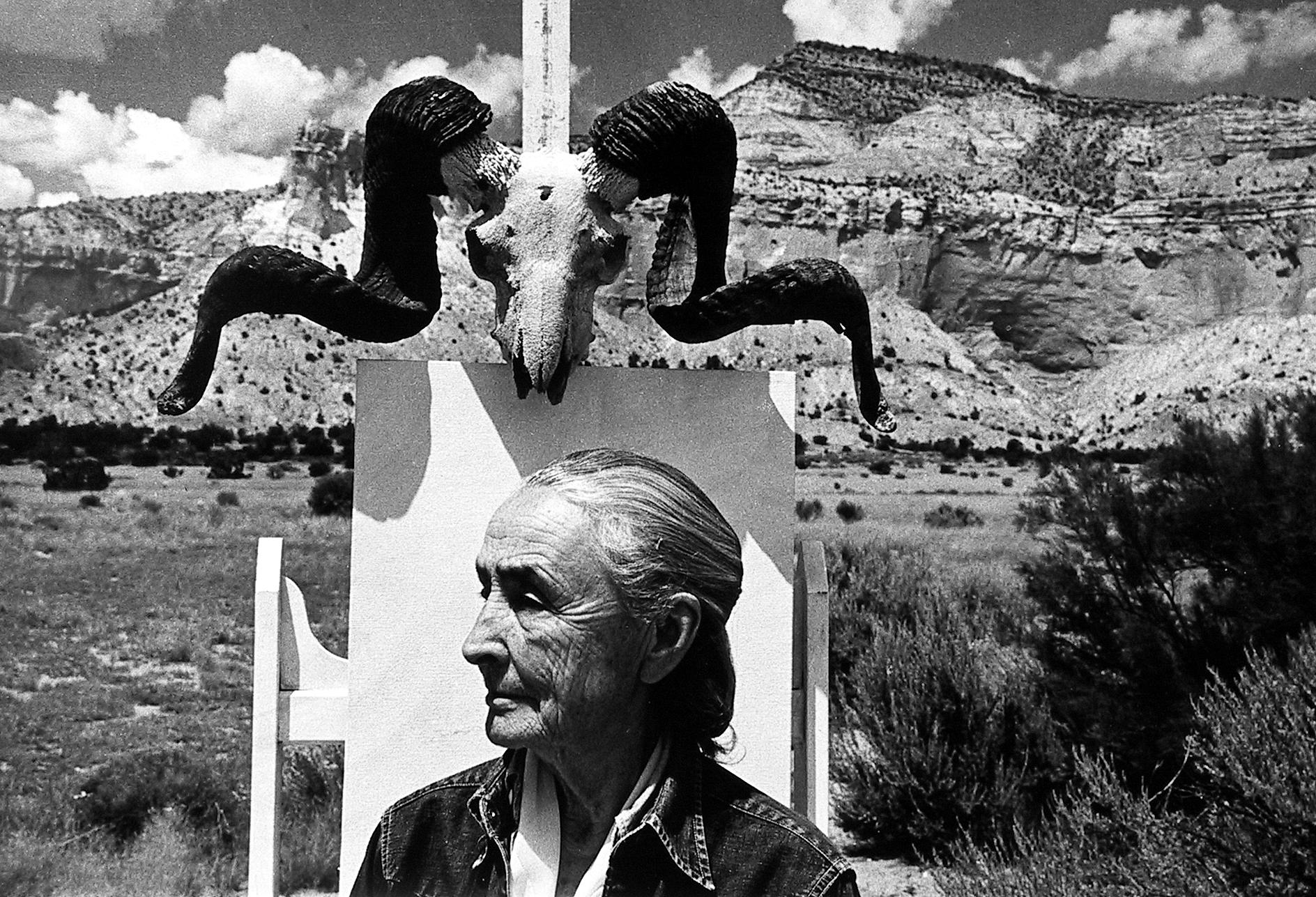

Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, Newman's client list expanded to include the most powerful figures in art, politics, science, and industry. He photographed presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson, industrialists like Alfred Krupp, and artists including Pablo Picasso, Marc Chagall, and Georgia O'Keeffe. His portrait of Krupp, the German armaments manufacturer, is one of the most psychologically charged images in portraiture: Newman lit the industrialist from below, his clasped hands and looming figure giving him a demonic, Mephistophelean appearance. Newman, who was Jewish, later acknowledged that the lighting was a deliberate choice — a quiet act of visual commentary on a man whose family fortune had been built on weapons that armed the Nazi war machine.

Newman's work appeared regularly in Life, Look, Harper's Bazaar, The New Yorker, Newsweek, and Vanity Fair, among many other publications. He was equally at home in the editorial and fine-art worlds, and he saw no contradiction between the two. For Newman, the assignment was not a constraint but a framework within which art could be made. He approached every sitting with meticulous preparation, researching his subjects and their work before the session and arriving with a clear idea of what he wanted the portrait to communicate, while remaining open to the accidents and improvisations that made each session unique.

Arnold Newman continued to photograph actively into his eighties, producing portraits of extraordinary vitality and formal invention until shortly before his death on 6 June 2006 in New York City. His archive encompasses more than sixty years of work and constitutes one of the most comprehensive visual records of twentieth-century cultural and political life ever assembled by a single photographer. His influence on the practice of portraiture has been immeasurable: the idea that a portrait should show not just who a person is but what they do, and that the environment can be as eloquent as the face, is now so deeply embedded in photographic practice that it is difficult to imagine a time before Newman demonstrated it. He did not merely photograph his subjects; he invented a way of seeing them.

Photography, as we all know, is not real at all. It is an illusion of reality with which we create our own private world. Arnold Newman

The defining image of environmental portraiture: the composer positioned at the lower corner of the frame, dominated by the angular form of a grand piano lid, transforming a portrait into a visual metaphor for the relationship between artist and instrument.

A landmark publication assembling Newman's portraits of the twentieth century's most important artists, from Picasso and Mondrian to de Kooning and Pollock, each photographed within the context of their creative world.

A deliberately unsettling portrait of the German industrialist, lit from below with clasped hands and a factory backdrop, in which Newman used every tool of photographic portraiture to make a moral statement about power and complicity.

Born in New York City on 3 March. Grows up in Atlantic City and Miami Beach in modest circumstances.

Takes a job at a chain portrait studio in Philadelphia after leaving the University of Miami, learning the mechanics of commercial portraiture.

First exhibition at the A.D. Gallery in New York draws the attention of Beaumont Newhall and Alfred Stieglitz, launching his career.

Photographs Piet Mondrian in his New York studio, producing one of the earliest and finest examples of environmental portraiture.

Creates the iconic portrait of Igor Stravinsky at the piano, which becomes one of the most reproduced photographs of the twentieth century.

Photographs Alfred Krupp in Essen, Germany, producing a deliberately sinister portrait that becomes one of the most discussed images in the history of portraiture.

Publishes Artists: Portraits from Four Decades, a comprehensive survey of his work photographing the century's most important creative figures.

Retrospective exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C., honouring six decades of photographic achievement.

Dies on 6 June in New York City. His legacy as the inventor of environmental portraiture remains unchallenged, and his influence on the genre continues undiminished.

Interested in discussing photography, collaboration, or just want to say hello? I’d love to hear from you.

Contact →