A singular chronicler of Los Angeles whose unflinching, formally rigorous photographs of the city's margins — its bus stops, homeless encampments, and contested landscapes — have redefined urban documentary photography as an art of patient, unsentimental witness.

Born 1947, Los Angeles, California — American

Anthony Hernandez was born in 1947 in Los Angeles, the city that would become the singular subject of his life's work. Raised in a working-class Mexican-American family, he grew up in the neighbourhoods of East Los Angeles and witnessed firsthand the social stratification, racial tension, and relentless urban transformation that would define his photographic vision. After graduating from high school, Hernandez served in the United States Army during the Vietnam War, an experience that marked him profoundly. Returning to Los Angeles in the late 1960s, he enrolled at East Los Angeles College, where he discovered photography and found in the camera a means of engaging with the world he had come home to — a world that seemed to him both familiar and newly strange.

His earliest serious work, produced in the early 1970s, was street photography in the classic tradition: black-and-white images of people on the streets of Los Angeles, shot with a 35mm camera in the rapid, intuitive manner of Garry Winogrand and Lee Friedlander. But even in these early images, Hernandez displayed a sensibility distinct from the New York school of street photography that dominated the era. His Los Angeles was not the dense, kinetic city of pedestrians and chance encounters; it was a sprawling, car-dependent landscape where people waited — at bus stops, on sidewalks, in parking lots — isolated figures in an engineered emptiness. The social content was there, but it was embedded in the spatial structure of the city itself.

By the late 1970s, Hernandez had begun the series that would establish his mature vision. Public Transit Areas, begun in 1979, concentrated on the bus stops of Los Angeles — those exposed, unshaded benches where the city's working poor sat waiting for buses that served a system designed primarily for the automobile. The photographs are formally precise, shot in bright Southern California light, and they document not merely the people who wait but the architecture of waiting itself: the concrete, the signage, the absence of shelter, the indifference of the built environment to its most vulnerable inhabitants. It was in this series that Hernandez began to shift from photographing people to photographing the spaces that revealed social conditions, a transition that would deepen over the following decades.

In the mid-1980s, Hernandez turned his attention to Rodeo Drive in Beverly Hills, producing a body of colour work that examined the opposite pole of Los Angeles's economic spectrum. The images of wealthy shoppers and luxury storefronts were shot with the same forensic detachment he had brought to the bus stops, and the juxtaposition with his earlier work created an implicit commentary on inequality that was all the more powerful for its refusal to editorialize. Hernandez never pointed fingers; he simply looked, and the looking was enough.

The series that brought Hernandez to international attention was Landscapes for the Homeless, produced between 1988 and 1992. Abandoning the human figure almost entirely, Hernandez photographed the sites where homeless people had lived — encampments beneath freeway overpasses, makeshift shelters in vacant lots, nests of blankets and cardboard in urban ravines — after their inhabitants had moved on or been cleared out. The resulting images are hauntingly beautiful and deeply unsettling: still lifes of poverty that transform discarded objects and improvised shelters into compositions of startling formal complexity. The absence of people in these photographs is itself a statement about visibility, erasure, and the limits of documentary representation. Hernandez understood that to photograph homeless people directly risked exploitation; by photographing their traces, he created a body of work that was at once more respectful and more devastating.

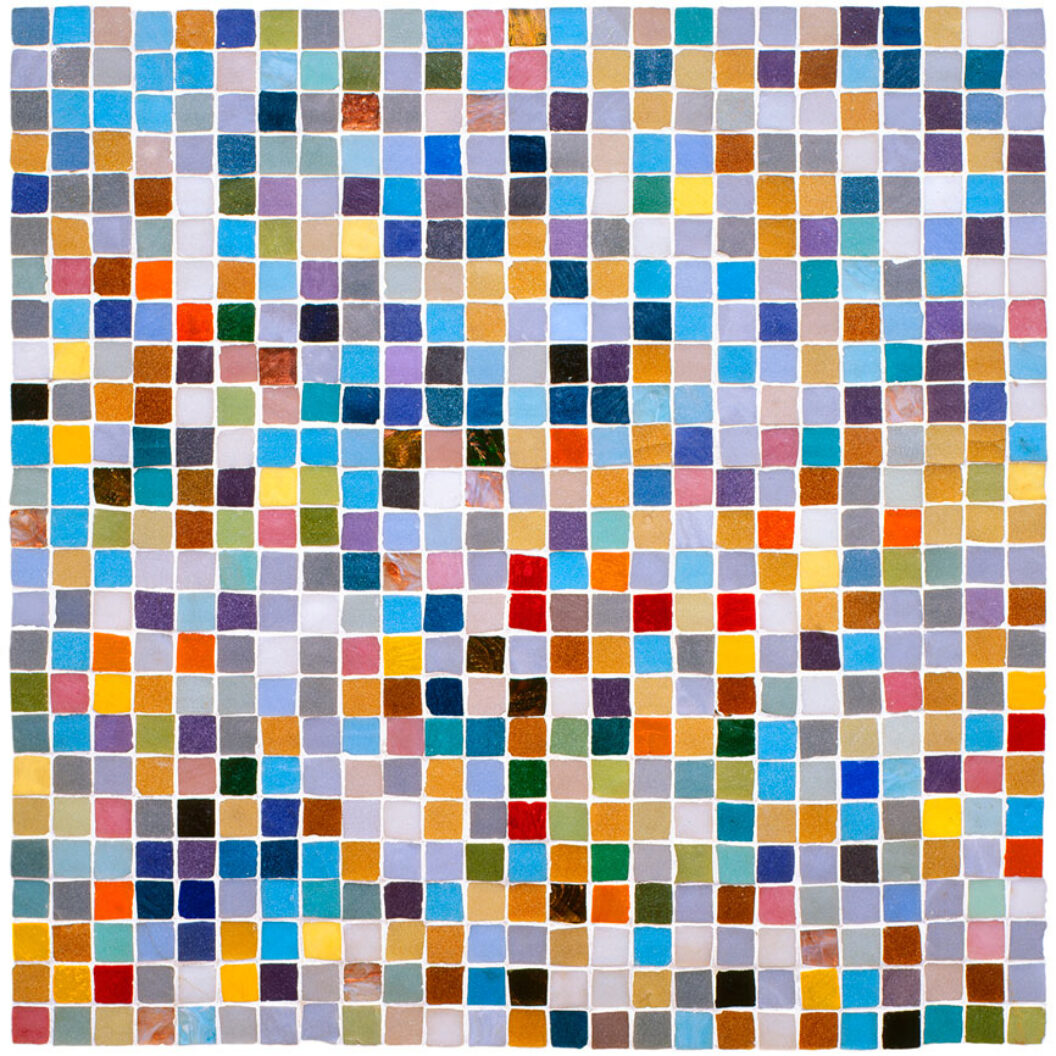

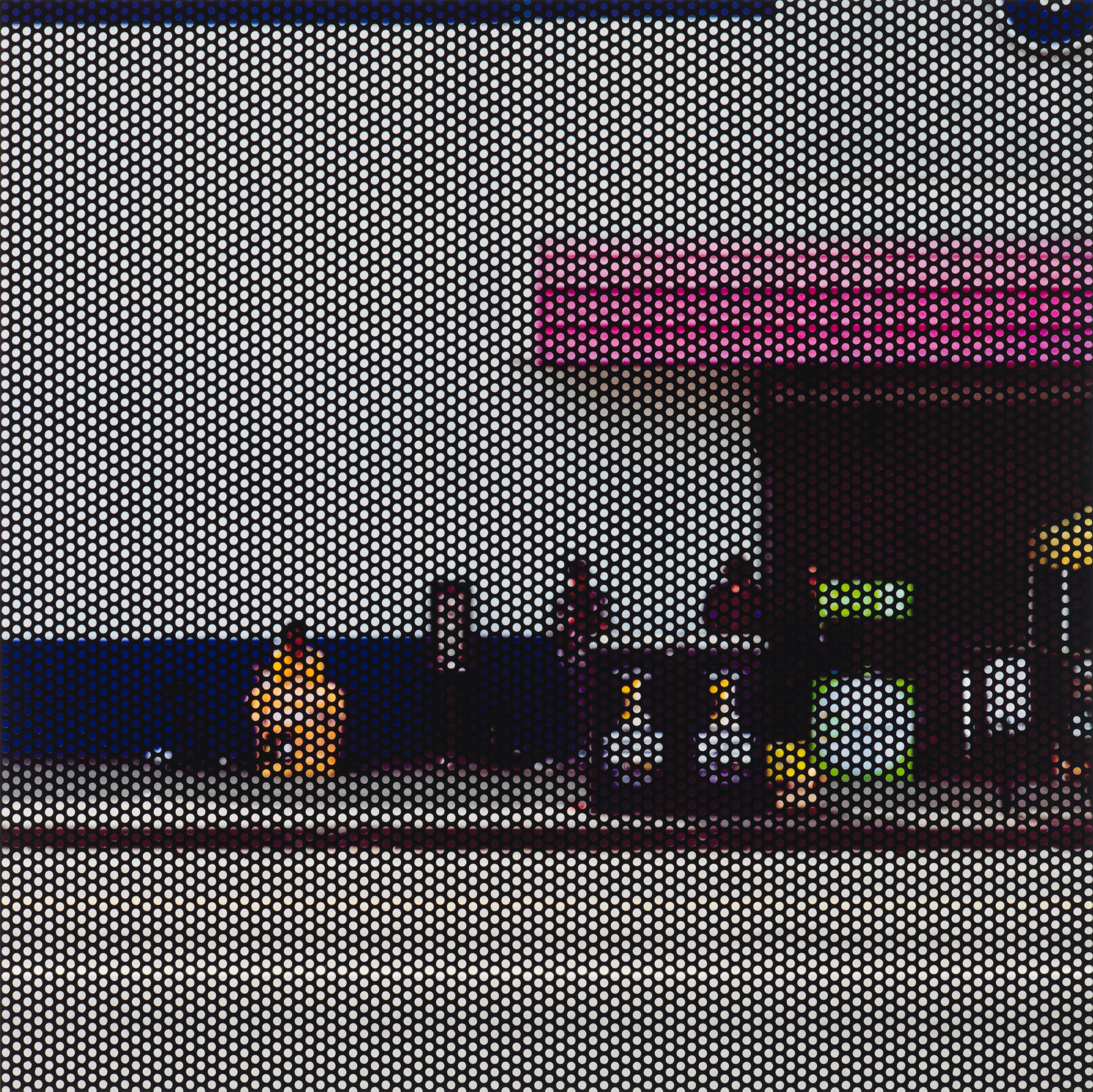

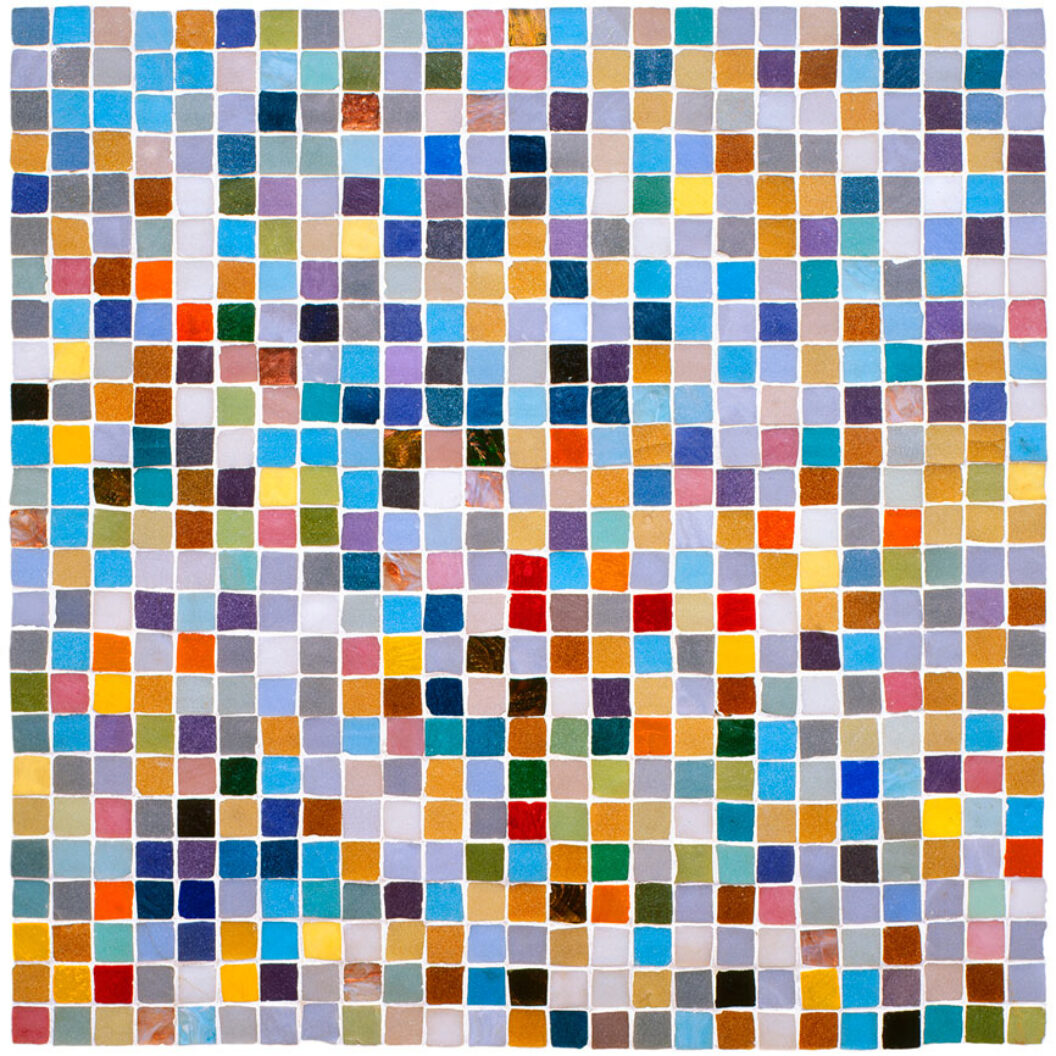

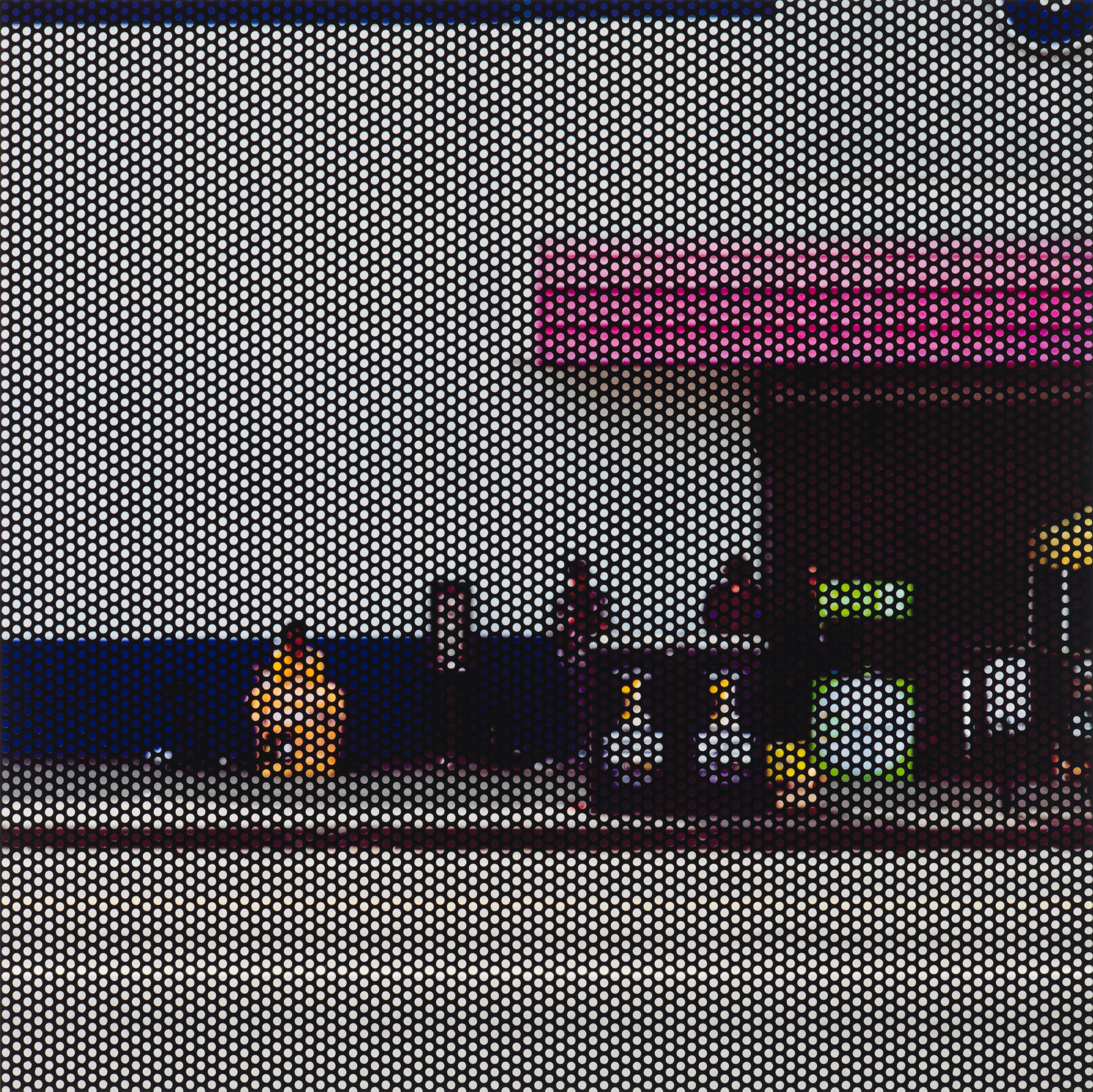

Throughout the 2000s and 2010s, Hernandez continued to expand his investigation of Los Angeles and its social landscape. His series on the waiting rooms of the California State Compensation Insurance Fund documented the bureaucratic spaces where injured workers navigated the system, while later bodies of work explored the material culture of the city's margins with an increasingly abstract and sculptural eye. His Screened Pictures series, begun in 2015, marked a significant formal departure, incorporating digital manipulation and layering to create images that hover between photography and painting, between document and hallucination.

Hernandez has received numerous honours, including a Guggenheim Fellowship and grants from the National Endowment for the Arts. His work is held in the collections of the Museum of Modern Art, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, and many other institutions. A major retrospective, Anthony Hernandez, was mounted by the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art in 2016, confirming his status as one of the most important photographers working in America. His contribution to the medium lies not only in the power of individual images but in the sustained, decades-long project of looking at one city with an attention so fierce and patient that it transforms the ordinary into the revelatory.

I photograph what the city does to its people, and what people do to the city. Anthony Hernandez

A study of Los Angeles bus stops and the people who wait at them, revealing the architecture of social neglect in a city designed for the automobile. The series marked Hernandez's shift from street photography to a more spatially driven investigation of urban inequality.

Photographs of abandoned homeless encampments in Los Angeles, capturing the material traces of invisible lives with a formal rigour that transforms discarded objects into compositions of unsettling beauty and social urgency.

A late-career series incorporating digital layering and manipulation, blending photographic observation with abstraction to create images that push the boundaries between documentation and artistic invention.

Born in Los Angeles, California. Grows up in the working-class neighbourhoods of East Los Angeles.

Serves in the United States Army during the Vietnam War. The experience profoundly shapes his subsequent worldview and artistic concerns.

Begins studying photography at East Los Angeles College, producing his first serious street photographs of the city.

Begins the Public Transit Areas series, documenting the bus stops and waiting spaces of Los Angeles with a new formal rigour.

Photographs Rodeo Drive in Beverly Hills, turning his lens on wealth and consumerism with the same detachment he brought to the city's margins.

Begins Landscapes for the Homeless, the series that will bring him international recognition and redefine his approach to documentary photography.

Photographs the waiting rooms of the California State Compensation Insurance Fund, extending his investigation into the bureaucratic spaces of the working poor.

Major retrospective exhibition at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, with an accompanying monograph surveying five decades of work.

Interested in discussing photography, collaboration, or just want to say hello? I’d love to hear from you.

Contact →