The towering master of American landscape photography whose luminous black-and-white images of the American West, combined with his pioneering Zone System of exposure control, elevated the medium to the realm of fine art and defined the visual identity of the wilderness for generations.

1902, San Francisco, California – 1984, Monterey, California — American

Ansel Easton Adams was born on 20 February 1902 in San Francisco, California, the only child of Charles Hitchcock Adams, a businessman whose family fortune had been built in the timber industry, and Olive Bray Adams. The great earthquake of 1906 threw the young Adams against a garden wall, breaking his nose and leaving him with a distinctive profile he would carry for life. A hyperactive and somewhat difficult child, he struggled in traditional schooling and was largely educated at home and through private tutors. His father, recognising the boy's restless intelligence, encouraged his early passion for music, and by the age of twelve Adams was practising the piano with a discipline that would later transfer directly to his photographic work.

In 1916, during a family holiday to Yosemite Valley, the fourteen-year-old Adams was given a Kodak No. 1 Box Brownie camera. The experience of Yosemite — its granite walls, waterfalls, and shifting light — overwhelmed him, and he returned to the valley nearly every summer for the rest of his life. For over a decade he pursued both music and photography in parallel, training seriously as a concert pianist while spending his summers photographing in the Sierra Nevada. It was not until the late 1920s that he committed fully to photography, convinced that the camera could serve as an instrument of artistic expression as powerful as the piano. The transition was not easy; he later said that the decision involved a leap of faith, abandoning a career in which his competence was assured for one in which the medium itself was still fighting for recognition as an art form.

Adams's early photographic style was influenced by the pictorialist tradition, with its soft focus and painterly effects, but by the early 1930s he had moved decisively toward a sharp, detailed approach that emphasised the intrinsic qualities of the photographic print. In 1932, he joined with Edward Weston, Imogen Cunningham, Willard Van Dyke, and several others to form Group f/64, named after the smallest aperture setting on a large-format camera, which produces the greatest depth of field and the sharpest possible image. The group's manifesto was a declaration of war against pictorialism: they believed in straight photography, in the unmanipulated negative, and in the expressive potential of pure photographic seeing. Adams became the group's most visible and articulate spokesman, and the principles of f/64 remained the foundation of his aesthetic throughout his career.

Together with the photographer Fred Archer, Adams developed the Zone System in 1939–40, a technical framework for controlling exposure and development that allowed the photographer to previsualize the final print at the moment of exposure. The system divided the tonal range from pure black to pure white into eleven zones, each representing a one-stop difference in exposure. By metering specific areas of a scene and placing them on the desired zone, the photographer could achieve precise control over the distribution of tones in the final image. The Zone System was not merely a technical tool; it was an embodiment of Adams's belief that the photograph begins in the mind's eye. He coined the term visualization to describe this process of seeing the finished print before the shutter is released, and it became the cornerstone of his teaching and writing.

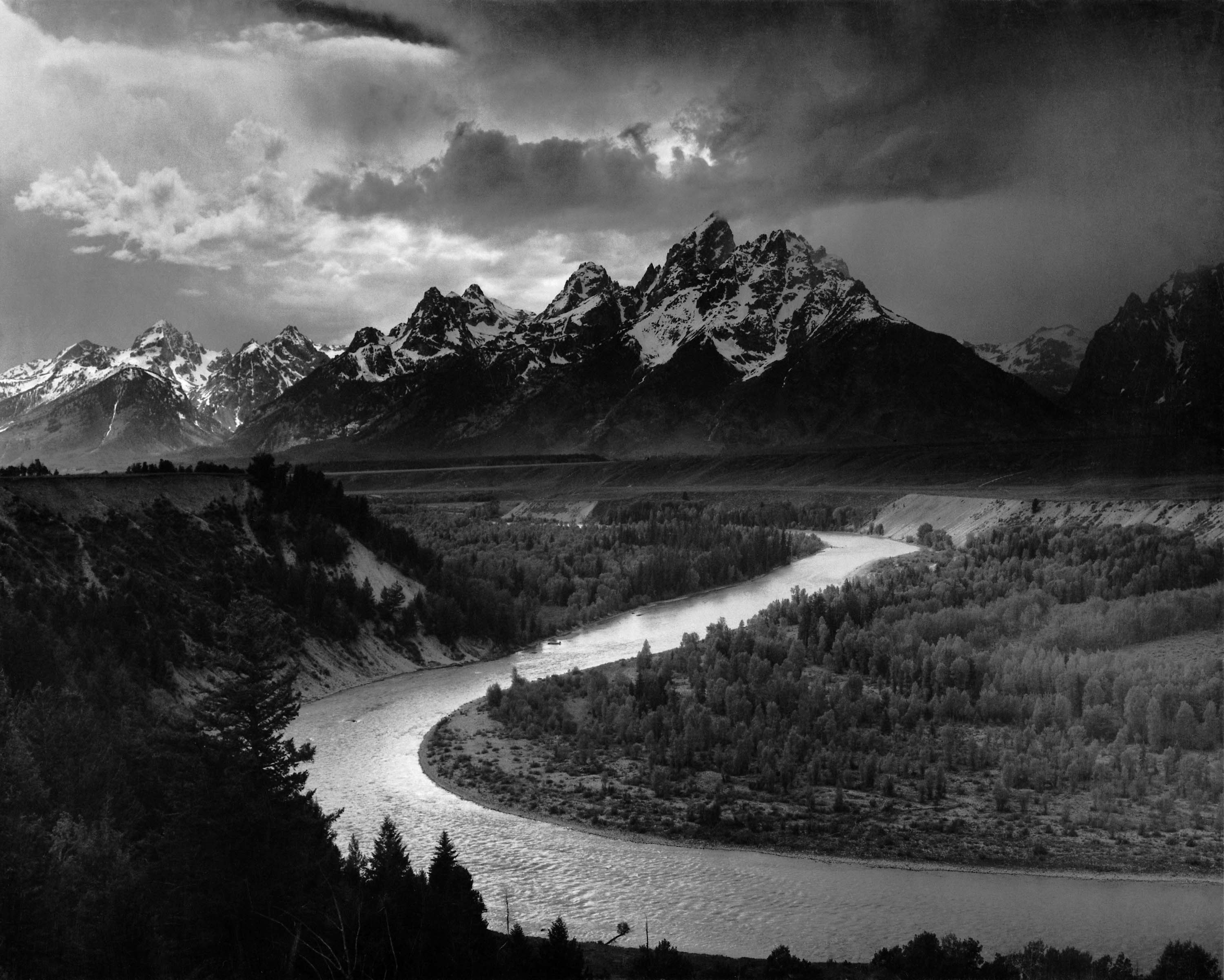

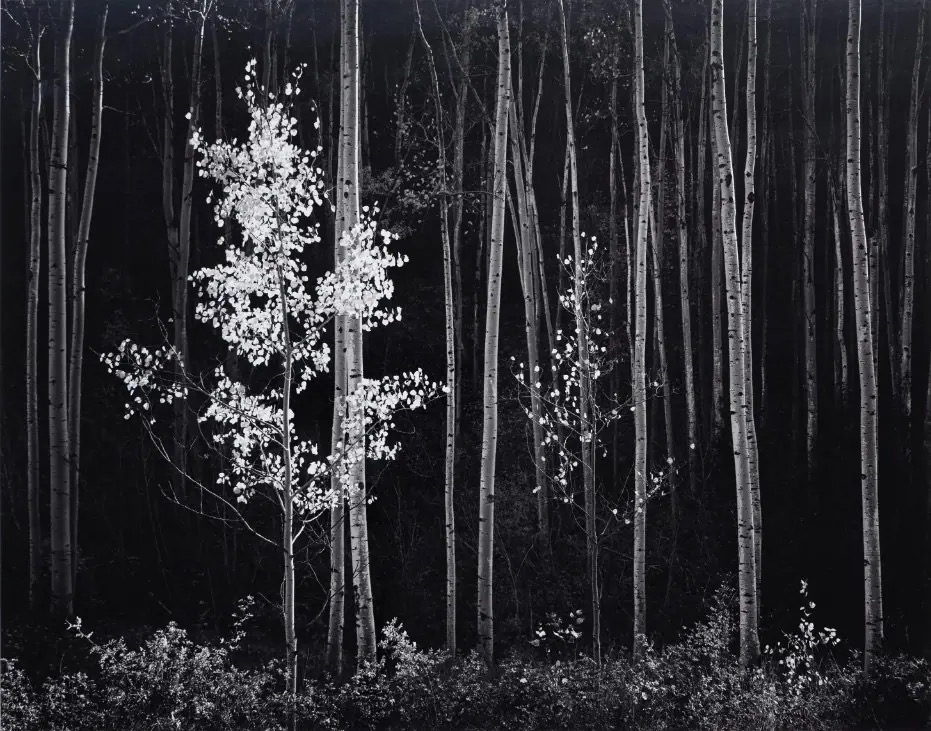

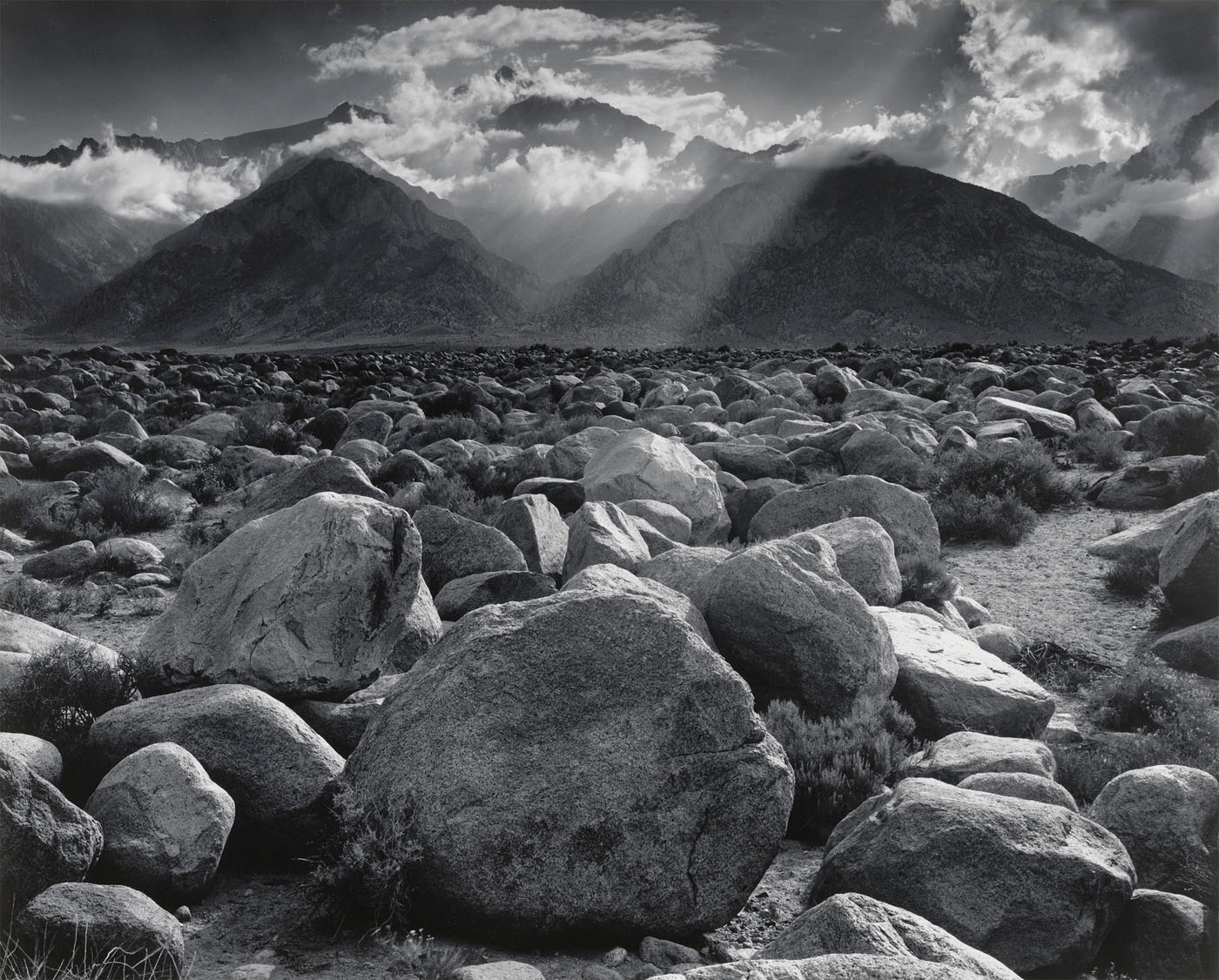

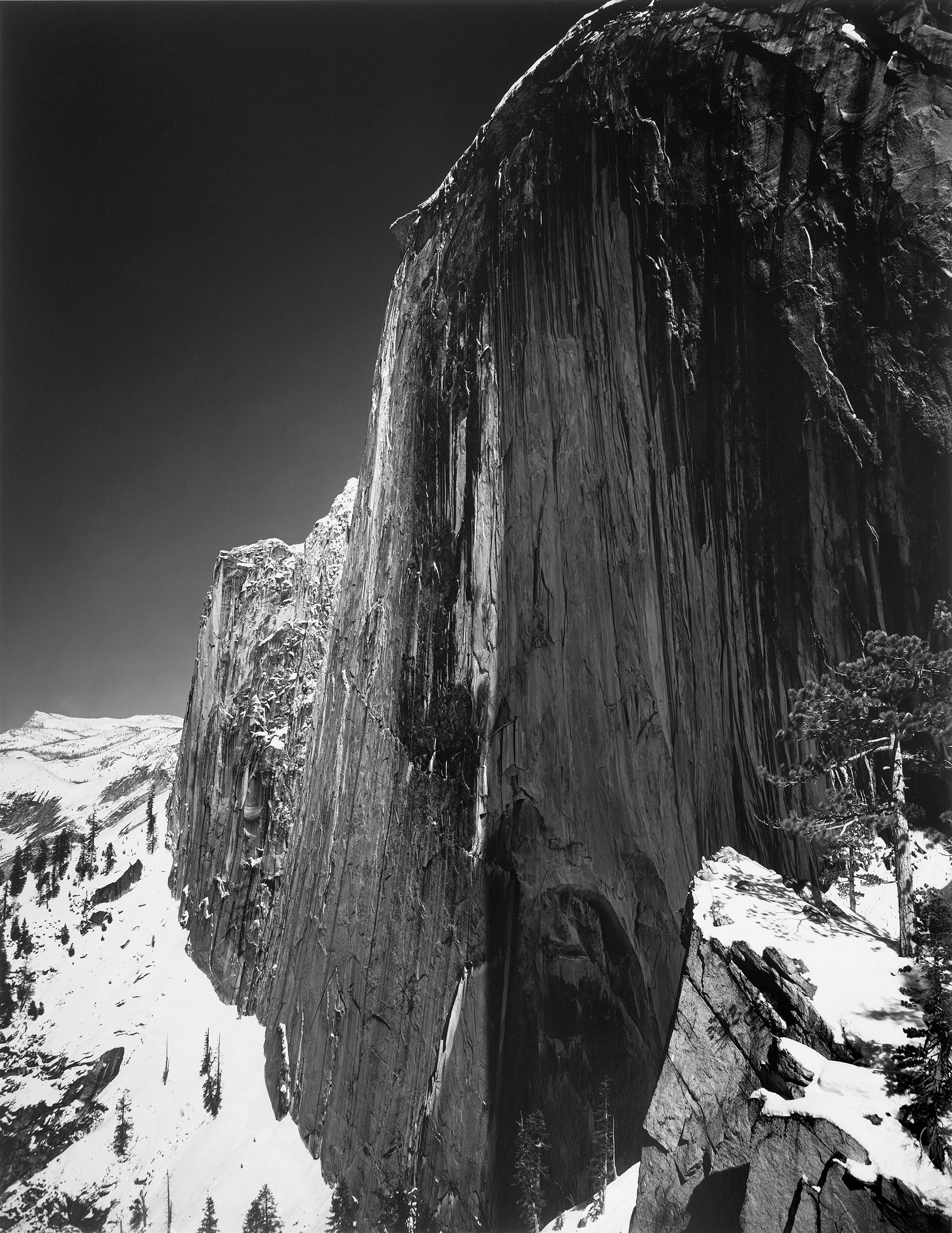

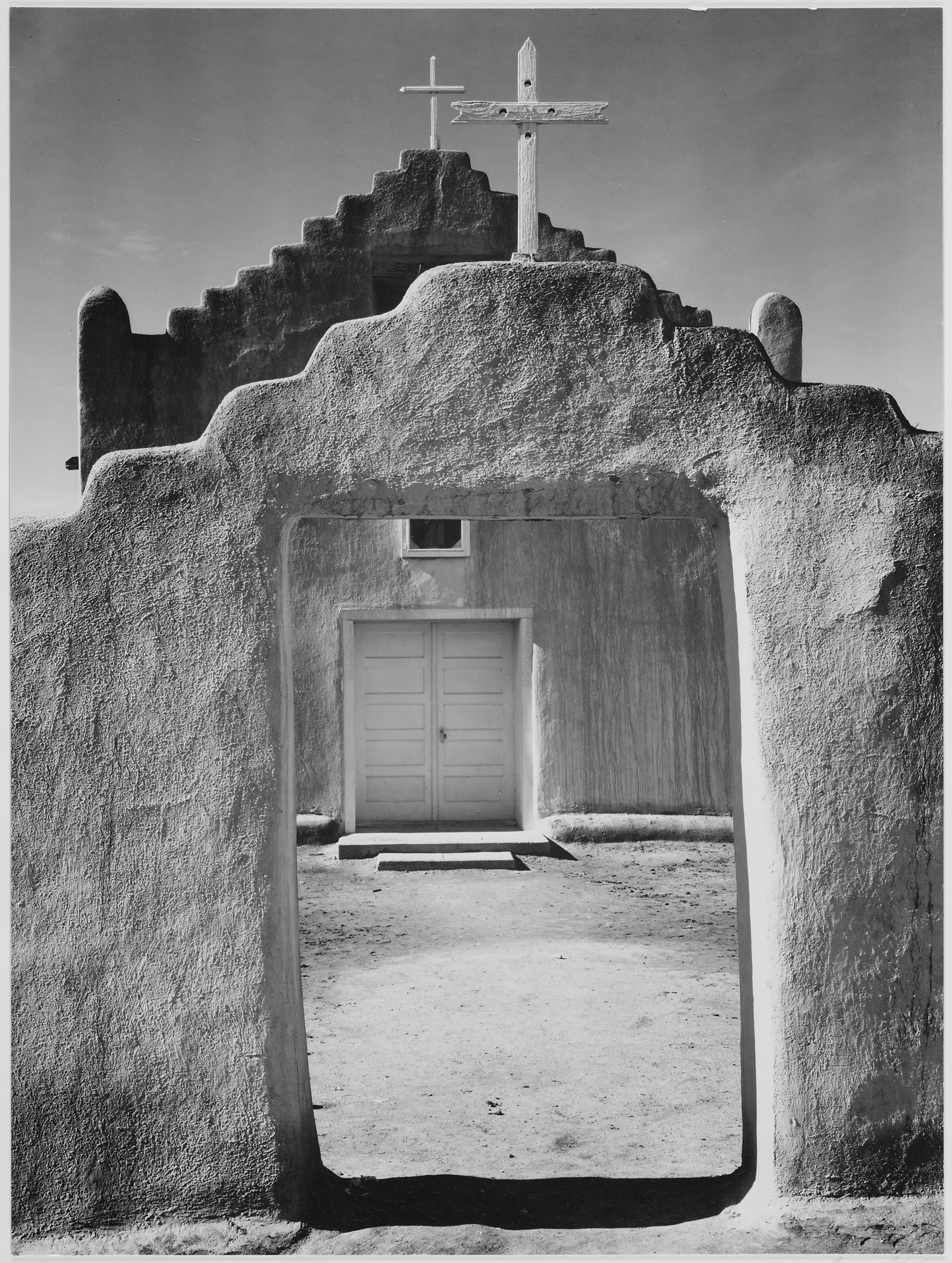

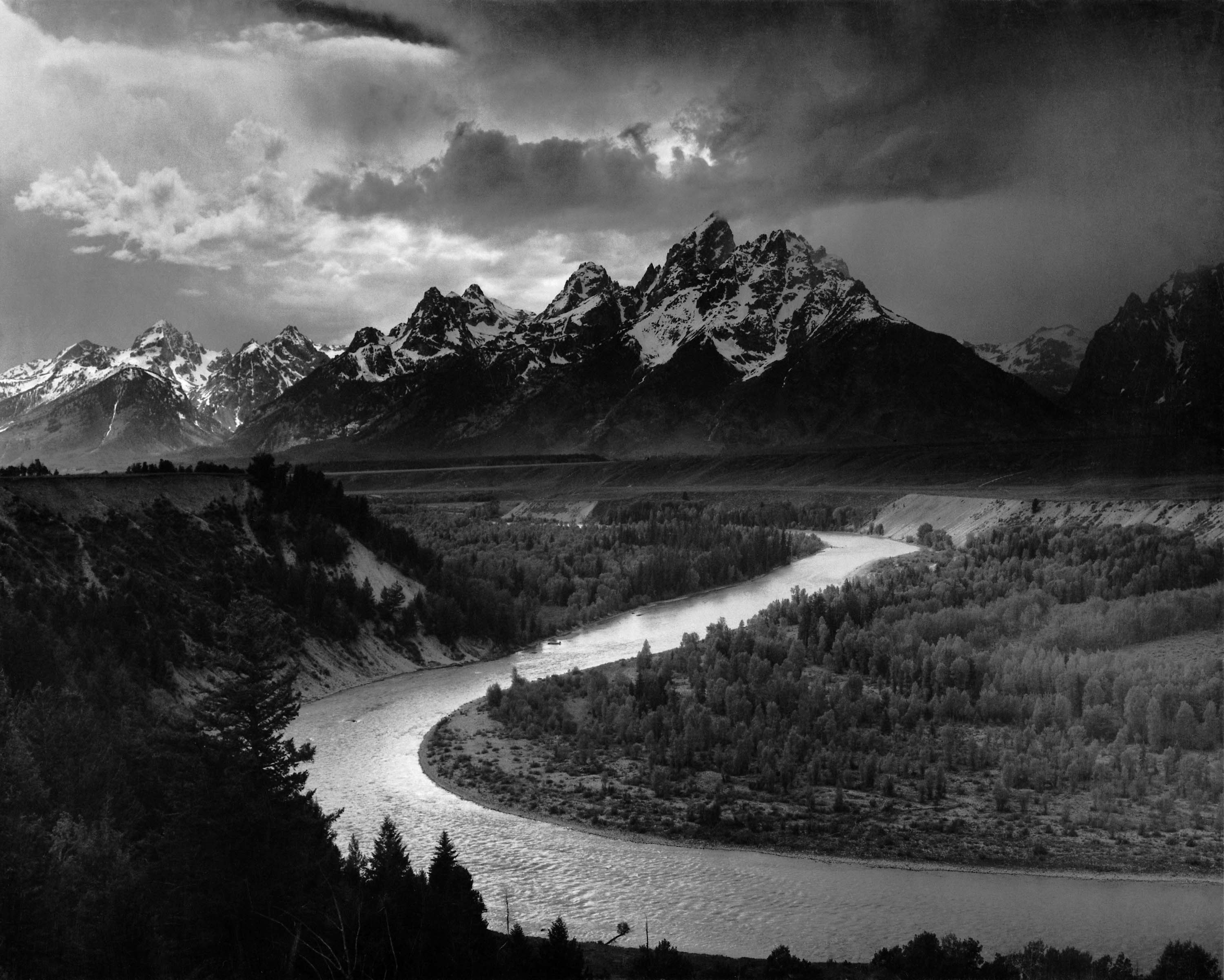

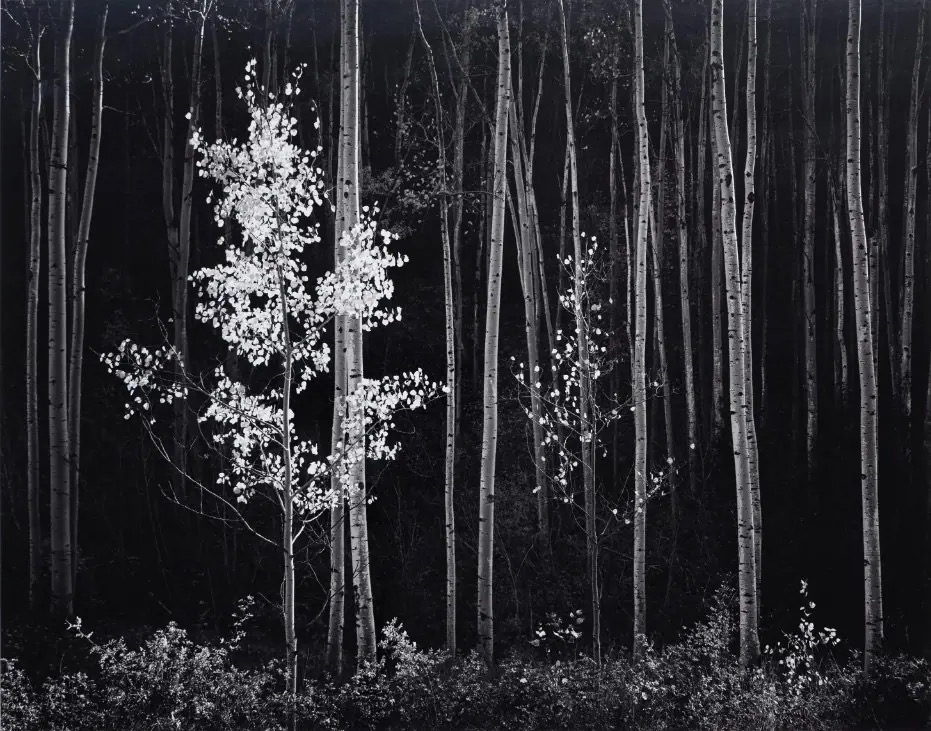

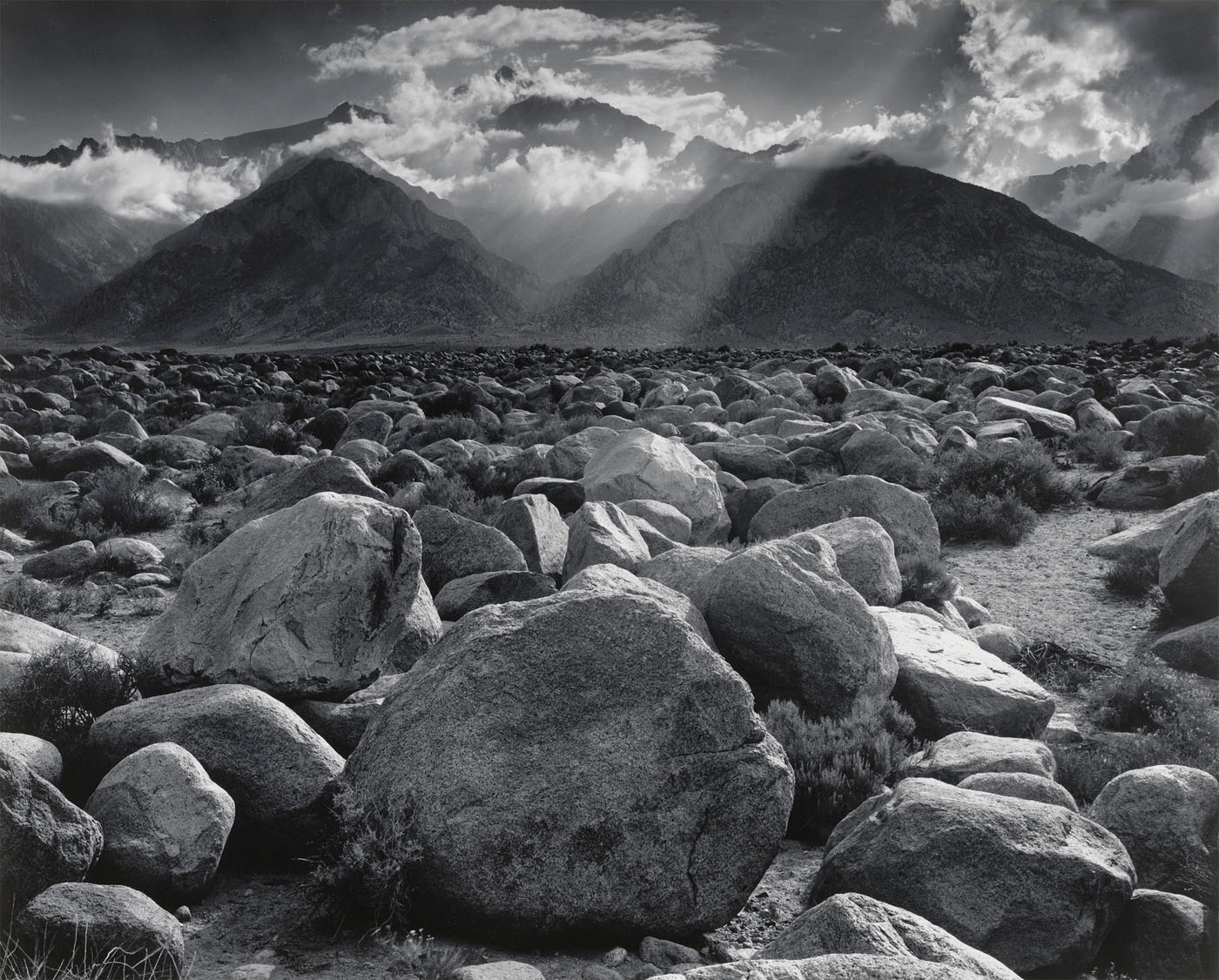

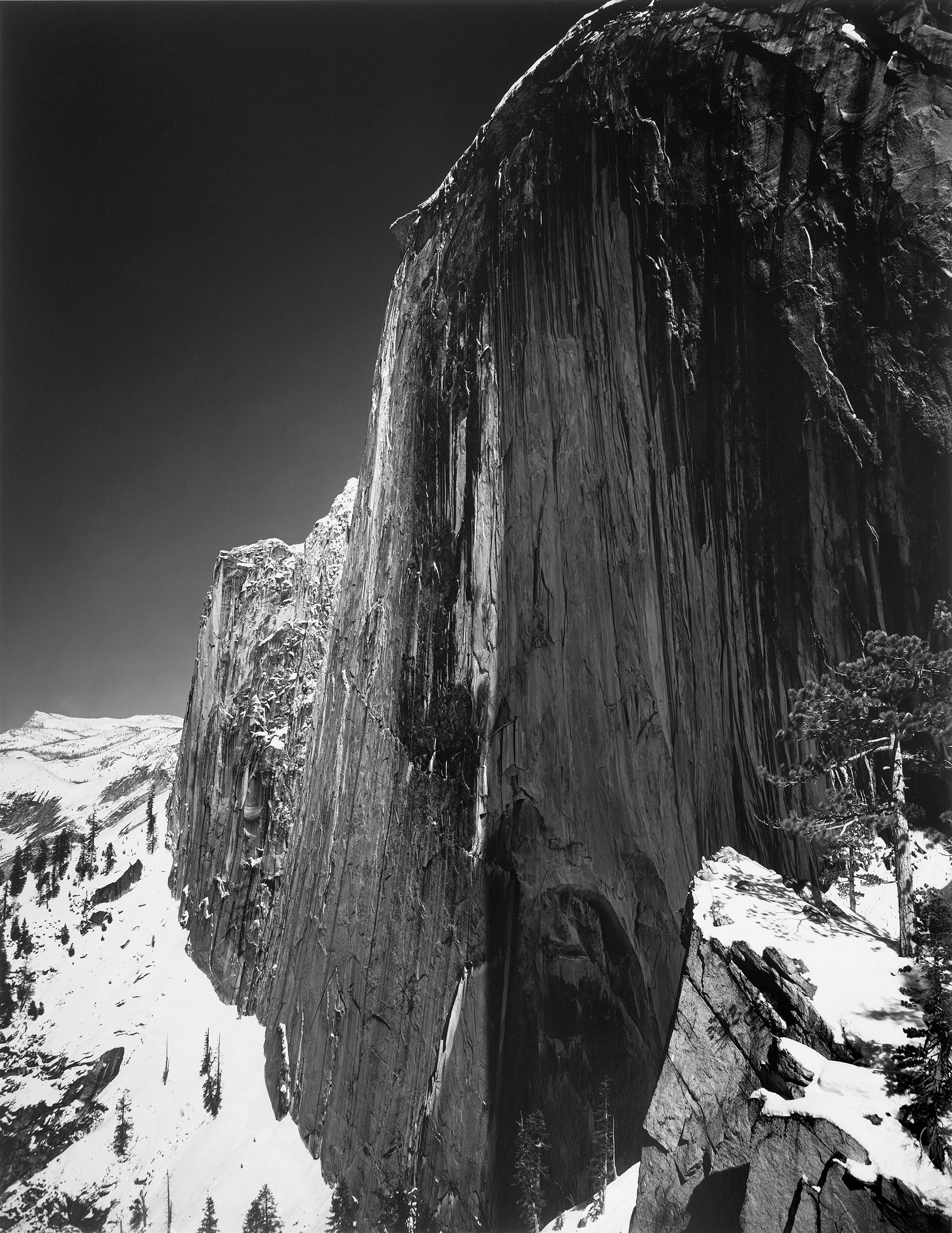

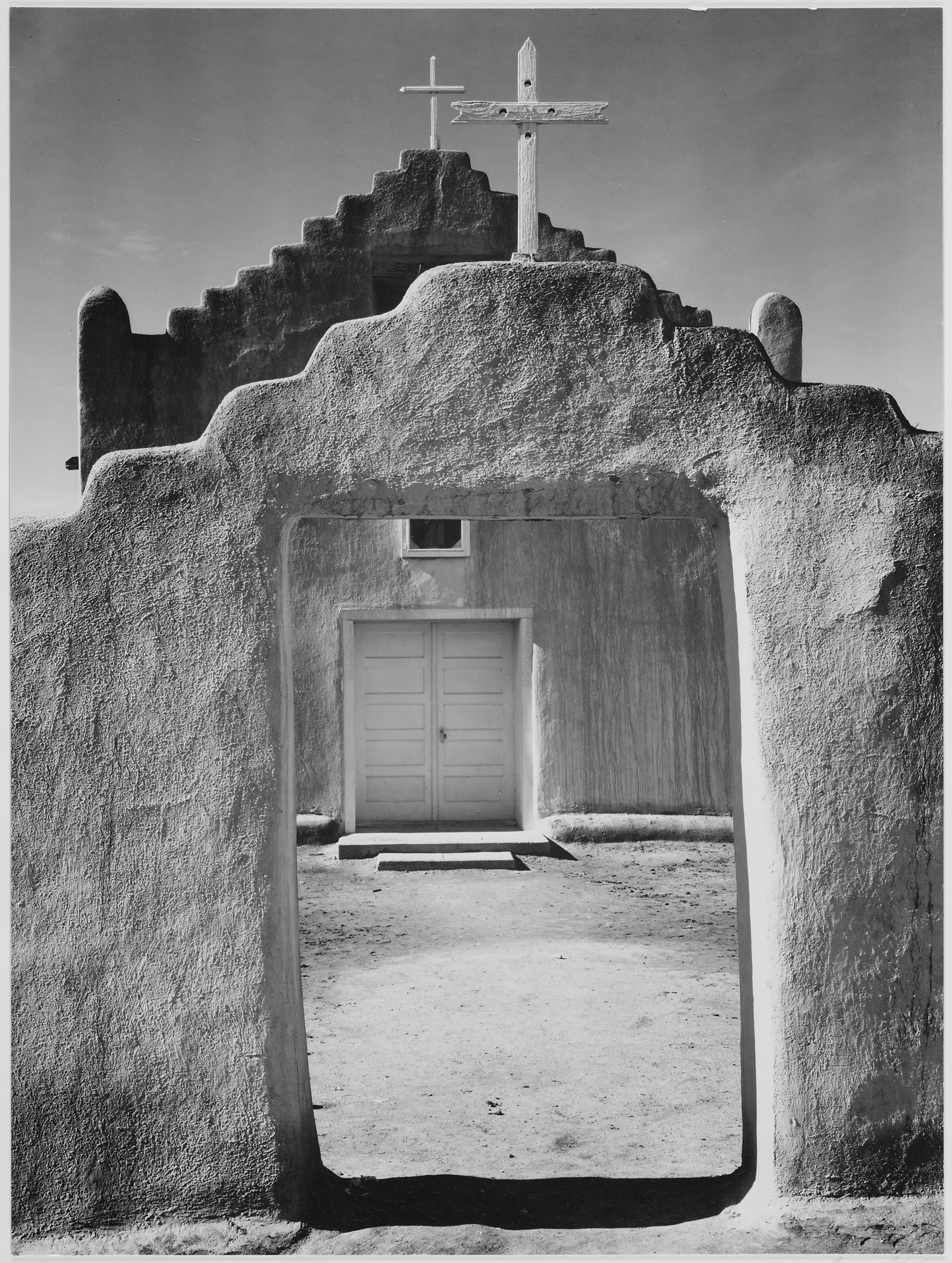

Adams's most celebrated images are his monumental landscapes of the American West: the soaring granite of Yosemite, the vast deserts of the Southwest, the volcanic peaks of Hawaii, and the glaciers of Alaska. These photographs are characterised by an extraordinary tonal range, from the deepest blacks to the most luminous whites, achieved through meticulous exposure, development, and printing. Adams spent hours in the darkroom, treating each print as a performance — a musical analogy he frequently invoked. The negative, he said, was the score; the print was the performance. No two prints were identical, and he returned to his most important negatives again and again over the decades, producing prints of increasing subtlety and power.

Beyond his artistic practice, Adams was a tireless advocate for the conservation of the American wilderness. He served on the board of directors of the Sierra Club for thirty-seven years and used his photographs as instruments of environmental persuasion. His images of the national parks were presented to presidents and members of Congress, and they played a significant role in the establishment of Kings Canyon National Park in 1940. Adams believed that his photographs could inspire the public to protect the land, and he pursued this mission with the same intensity he brought to his art. His correspondence with political leaders, his testimony before Congress, and his tireless lecturing made him one of the most effective environmental advocates of the twentieth century.

Adams was also a prolific writer and educator. His technical manuals — The Camera, The Negative, and The Print — published between 1948 and 1950 and revised throughout his life, remain the most comprehensive and lucid guides to photographic technique ever written. He taught workshops at Yosemite and in other locations for decades, and his students carried his methods and philosophy into every corner of the photographic world. He received the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1980, and when he died on 22 April 1984, in Monterey, California, he was mourned not only as the greatest landscape photographer in the history of the medium but as a figure who had fundamentally changed how Americans saw their own land.

Adams's legacy extends far beyond any single image. He demonstrated that photography could achieve a grandeur and emotional depth equal to any other art form. He proved that technical mastery and artistic vision were not opposed but inseparable. And he showed that the camera could be a force for good in the world, a tool not only for making beautiful pictures but for preserving the beauty of the earth itself. His influence on landscape photography, on the fine-art print tradition, and on the environmental movement remains immeasurable, and his images of the American West continue to define, for millions of people, the very idea of wilderness.

You don't take a photograph, you make it. Ansel Adams

A portfolio of magnificent large-format photographs of the High Sierra, produced for the Sierra Club, that established Adams as the preeminent landscape photographer of the American West and advanced the cause of wilderness preservation.

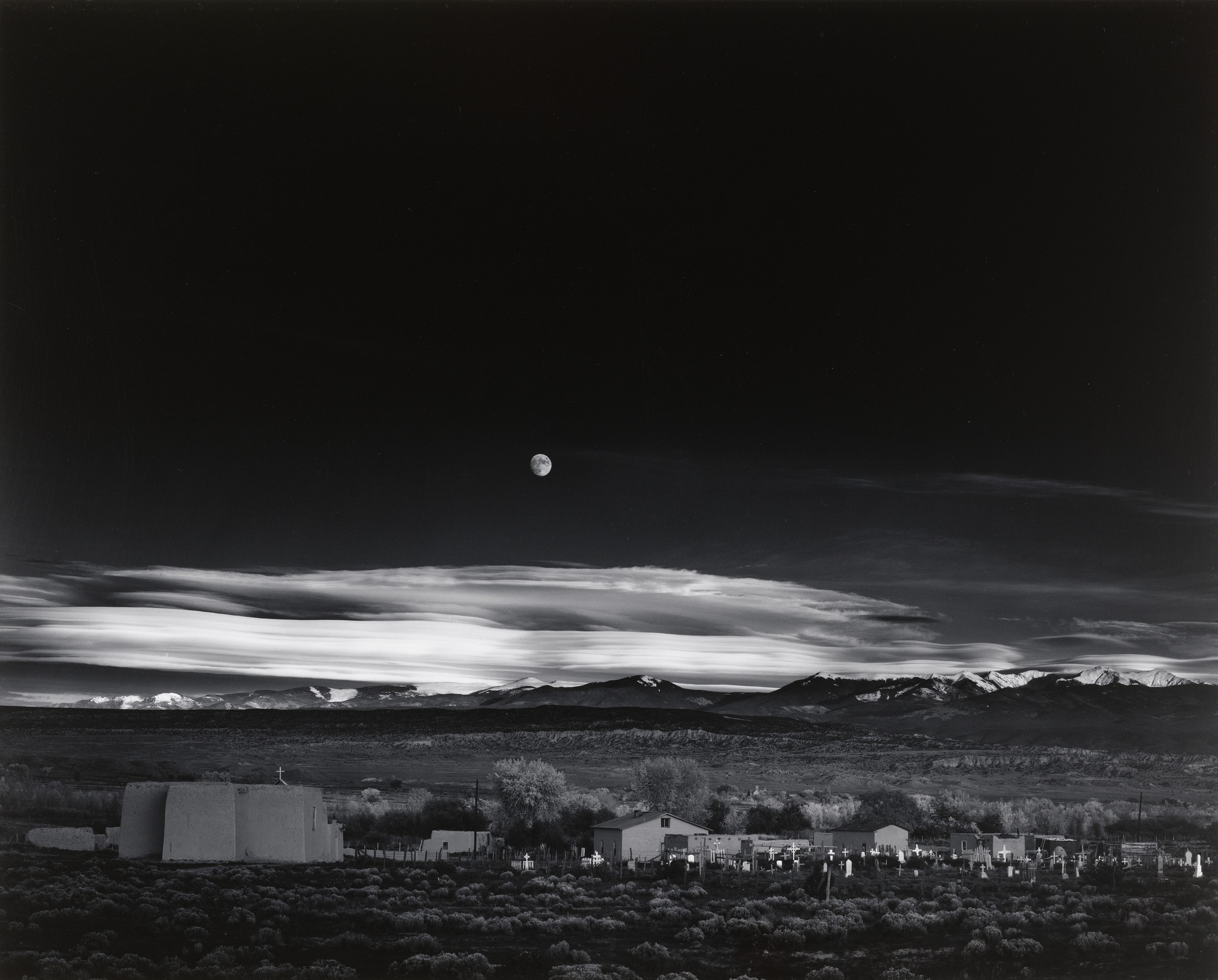

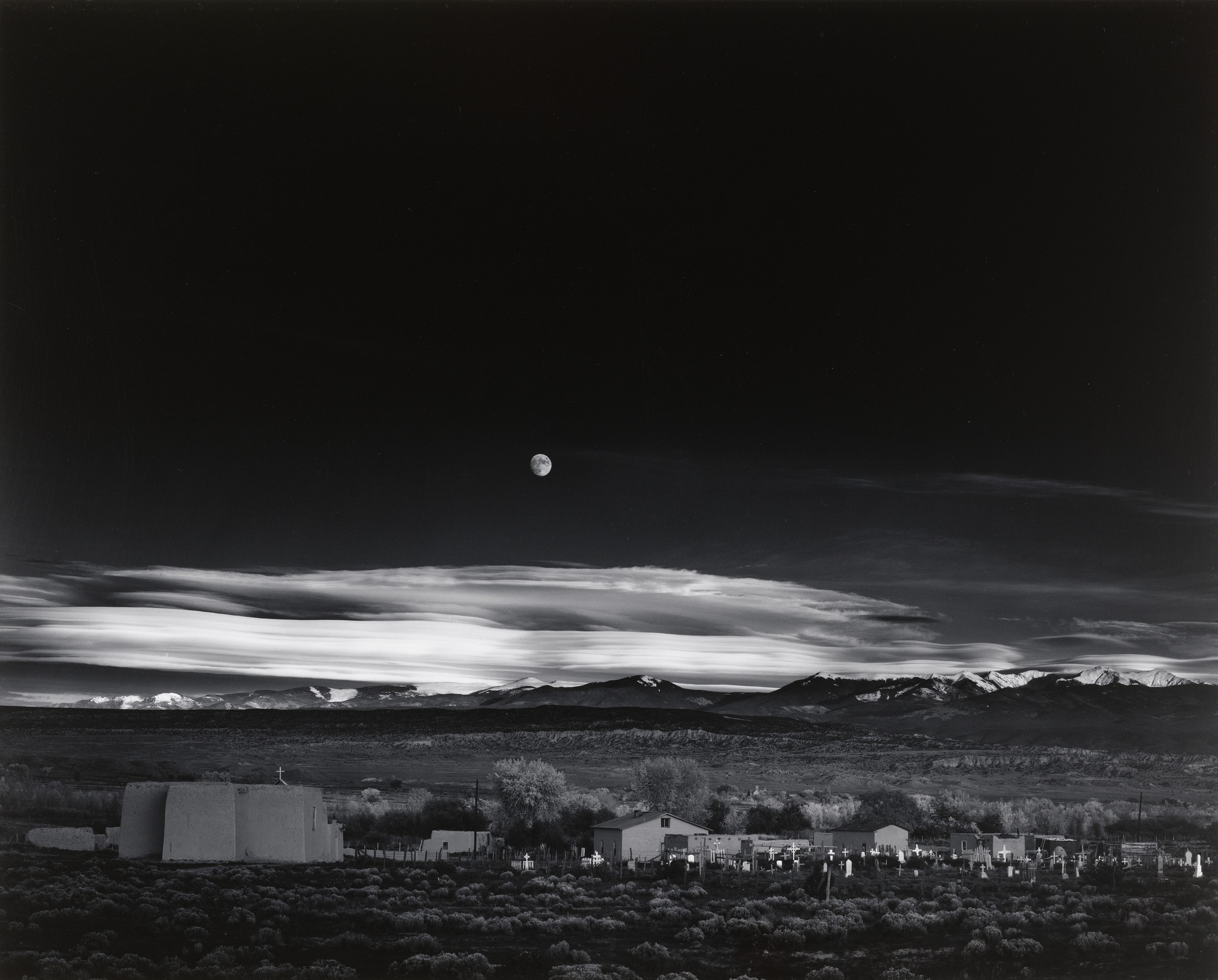

Perhaps the most famous photograph in the history of the medium, capturing the moon rising over a small village with a cemetery of white crosses glowing in the fading sunlight against a darkening sky. Adams printed this image hundreds of times over four decades, each print a new interpretation.

A landmark Sierra Club exhibition and book created with Nancy Newhall, combining Adams's photographs with Newhall's text in a passionate argument for conservation that helped launch the modern environmental movement.

Born in San Francisco, California. Raised in the sand dunes of the Golden Gate, where the natural landscape shapes his earliest sensibilities.

First visit to Yosemite Valley at age fourteen. Receives his first camera, a Kodak No. 1 Box Brownie, and begins a lifelong relationship with the landscape.

Creates Monolith, The Face of Half Dome, the image he later identified as his first true visualization — the moment he learned to see the final print before releasing the shutter.

Co-founds Group f/64 with Edward Weston, Imogen Cunningham, and others, championing straight photography and sharp-focus realism against the pictorialist tradition.

First one-man exhibition at Alfred Stieglitz's gallery, An American Place, in New York. Stieglitz's approval confirms Adams's standing in the art world.

Develops the Zone System with Fred Archer, providing photographers with a precise method for controlling tonal range from exposure through final print.

Photographs Moonrise, Hernandez, New Mexico, which becomes the most reproduced and recognised landscape photograph in history.

Establishes the first fine-art photography department at the California School of Fine Arts (now San Francisco Art Institute), with Minor White as his colleague.

Receives the Presidential Medal of Freedom from President Jimmy Carter for his contributions to art and environmental conservation.

Dies on 22 April in Monterey, California. Congress later designates a wilderness area in the Sierra Nevada as the Ansel Adams Wilderness in his honour.

Interested in discussing photography, collaboration, or just want to say hello? I’d love to hear from you.

Contact →