Anders Petersen was born in 1944 in Solna, a suburb of Stockholm, and grew up in a middle-class Swedish household that gave little indication of the raw, transgressive world he would later make his own as a photographer. As a young man, he was restless and uncertain of his direction, drifting through various jobs and experiences before discovering photography in the mid-1960s. The decisive encounter came when he enrolled at Christer Strömholm's photography school in Stockholm, where the charismatic Swedish master taught not technique but a philosophy of seeing — an approach to photography rooted in personal engagement, emotional honesty, and a willingness to enter into the lives of one's subjects without pretence or distance.

Strömholm's influence on Petersen was profound and lasting. From his teacher, Petersen absorbed the conviction that photography should be an act of intimate exchange rather than detached observation, and that the most powerful images emerge not from technical mastery but from the depth of the photographer's engagement with the people and places before the lens. This philosophy found its fullest expression in the work that would make Petersen's name and that remains, more than five decades later, one of the most celebrated bodies of documentary photography in European history: Café Lehmitz.

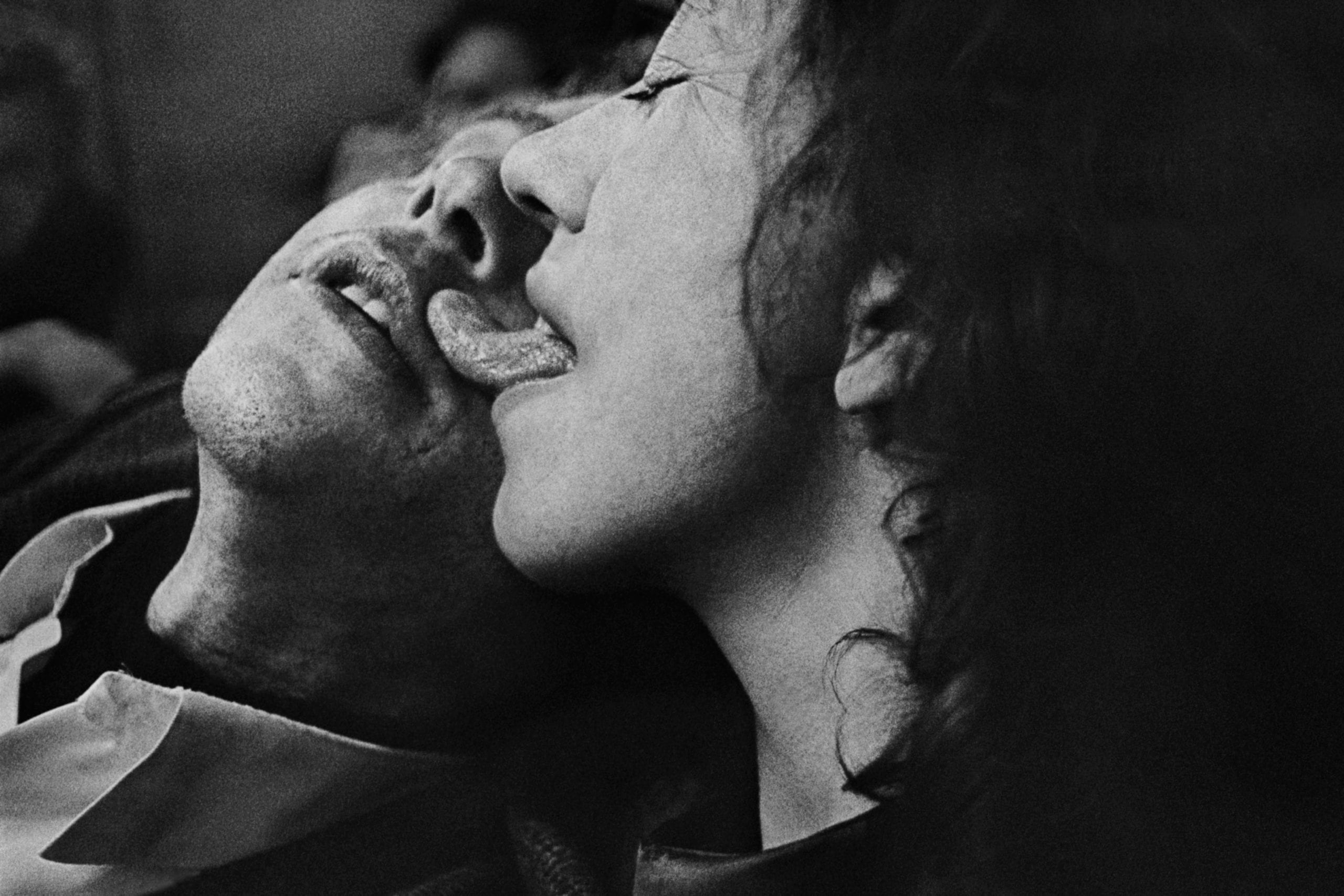

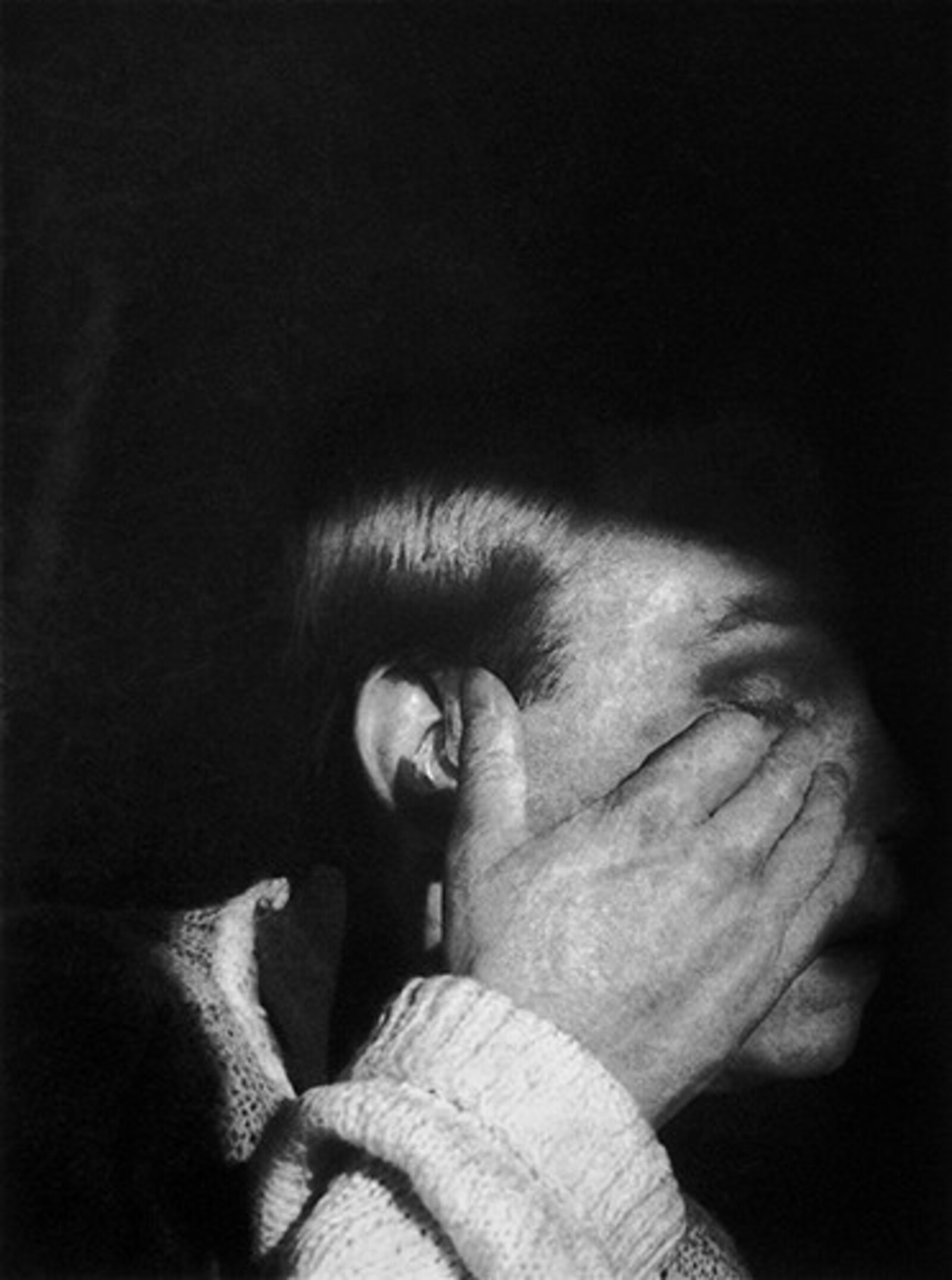

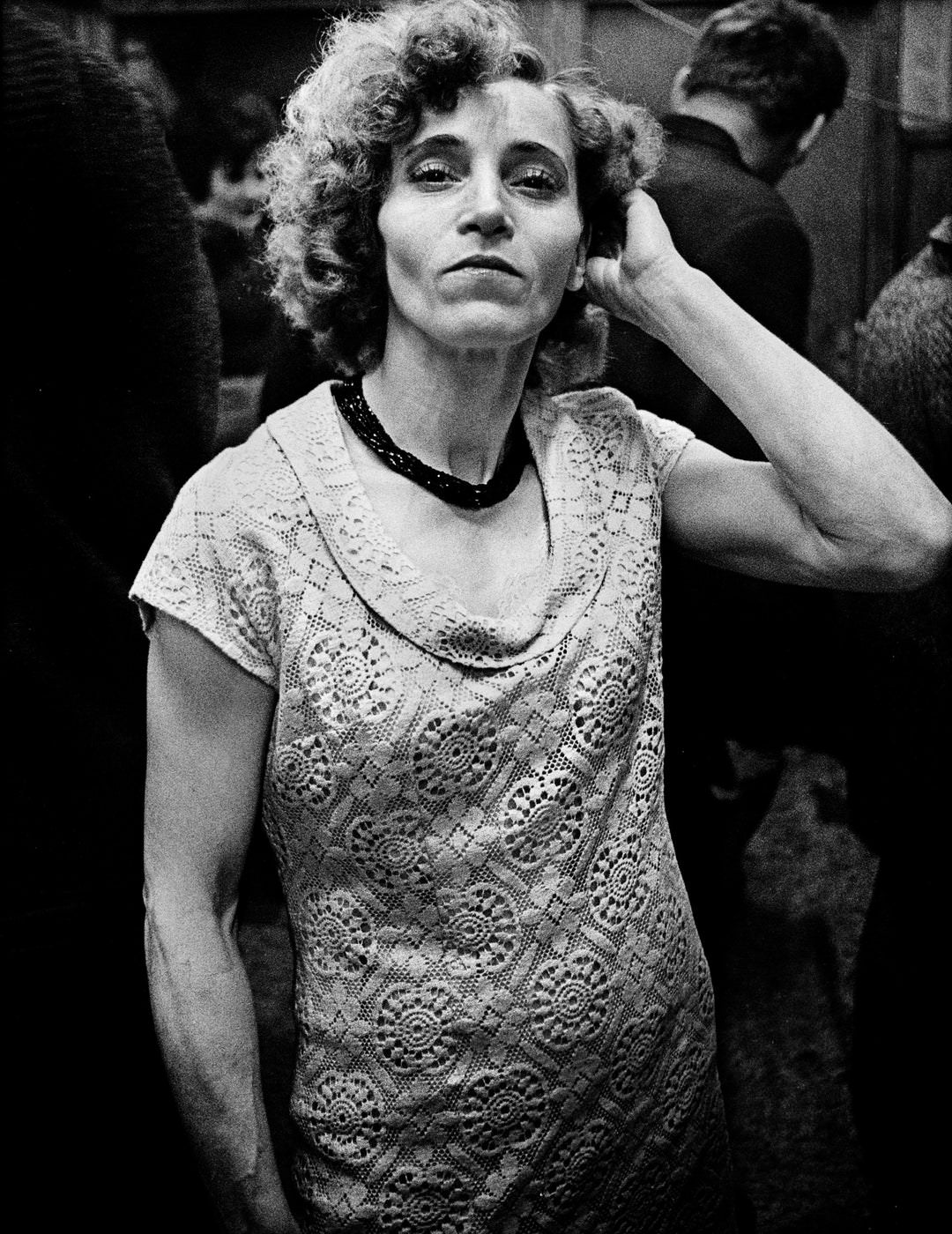

Between 1967 and 1970, Petersen spent extended periods at Café Lehmitz, a working-class bar on the Reeperbahn in Hamburg's St. Pauli district. The café was a gathering place for drinkers, sex workers, sailors, drifters, and night-owls — a community of people living on the margins of respectable society. Petersen did not arrive as a journalist or a social worker; he came as a friend, a fellow drinker, and eventually as a trusted member of the café's nightly community. He drank with the regulars, shared their tables, listened to their stories, and photographed them with a closeness and tenderness that could only have come from genuine affection and trust. The resulting photographs — grainy, high-contrast, often blurred, shot in available light with a small-format camera — capture moments of raw human experience: a couple embracing, a woman laughing with her head thrown back, a man slumped over a table, two friends arm in arm on the street outside.

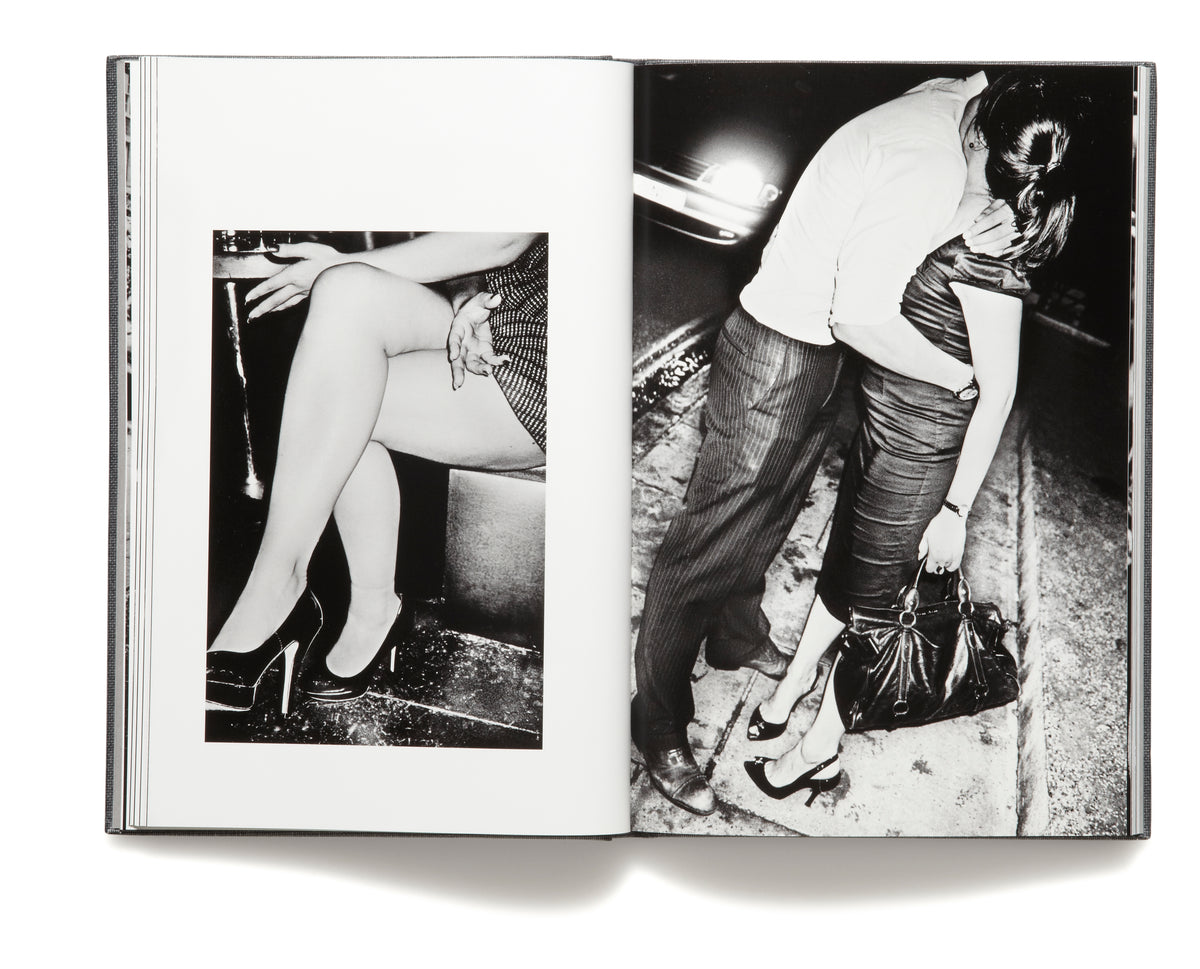

The Café Lehmitz photographs were first published as a book in 1978 by Schirmer/Mosel, and they have never gone out of print. The book was reissued in an expanded edition in 2015 and remains one of the most influential photobooks in the documentary tradition. Its impact has been felt across generations of photographers, from the Scandinavian documentary school to the wider European and Japanese traditions of intimate, subjective photography. The work demonstrated that documentary photography need not be cold, clinical, or detached to be truthful; on the contrary, it argued that the deepest truths emerge only when the photographer is willing to become vulnerable, to surrender the safety of the observer's position and enter fully into the world being photographed.

Following Café Lehmitz, Petersen continued to work in a similar register of intimate, emotionally direct photography, but he expanded his range of subjects and locations. He spent time in Swedish prisons, producing the book Fångelse (1984), which brought the same empathetic closeness to the lives of inmates. He photographed in psychiatric institutions, nursing homes, and other closed worlds that most people never see, always with the same commitment to treating his subjects not as specimens or symbols but as fellow human beings deserving of dignity and attention. His work in these environments was never voyeuristic or exploitative; it was grounded in long periods of presence and engagement that allowed trust to develop naturally.

From the 1990s onward, Petersen's work became more expansive and diaristic. He began producing what he called City Diaries — intensely personal photographic journals made in cities around the world, from Tokyo and Rome to Lisbon and Havana. These bodies of work were less focused on specific communities than on the texture of urban experience itself: faces in crowds, hands, bodies, food, streets, light, shadow, and the fleeting moments of connection and disconnection that make up the fabric of city life. The City Diaries extended the intimate, instinctive approach of the Lehmitz work into a broader, more fragmented visual language that anticipated the diaristic mode that has since become widespread in contemporary photography.

Petersen's influence on younger photographers has been enormous, particularly in Scandinavia and Japan, where his raw aesthetic and philosophy of closeness have inspired entire movements. His former students at various photography schools have gone on to distinguished careers, and his workshops and lectures continue to draw aspiring photographers from around the world. He has received numerous honours, including the Swedish government's cultural award and retrospective exhibitions at major European institutions. His work is held in the collections of the Moderna Museet in Stockholm, the Bibliothèque nationale de France, and many other museums.

Now in his eighties, Petersen continues to photograph with the same restless energy and emotional directness that characterised his earliest work. His legacy is not a style to be imitated — though many have tried — but a way of being in the world with a camera: open, unguarded, hungry for experience, and profoundly respectful of the people who allow themselves to be seen.