The tireless champion who fought to establish photography as a fine art, founding galleries, journals, and movements that transformed the medium from craft to high culture and reshaped the landscape of American modernism.

1864, Hoboken, New Jersey – 1946, New York City — American

Alfred Stieglitz was born on January 1, 1864, in Hoboken, New Jersey, the eldest son of German-Jewish immigrants who had prospered in the wool trade. His father, Edward Stieglitz, was a cultured man who valued the arts and provided his children with a privileged upbringing that included private education and, crucially, an extended period of study in Europe. In 1881, the family moved to Germany, and the young Stieglitz enrolled at the Technische Hochschule in Berlin to study mechanical engineering. It was there, in 1883, that he purchased his first camera and fell under the influence of Hermann Wilhelm Vogel, a photochemist who introduced him to the technical and aesthetic possibilities of the medium. Within a few years, Stieglitz had abandoned engineering entirely and devoted himself to photography with a single-minded intensity that would characterise the rest of his life.

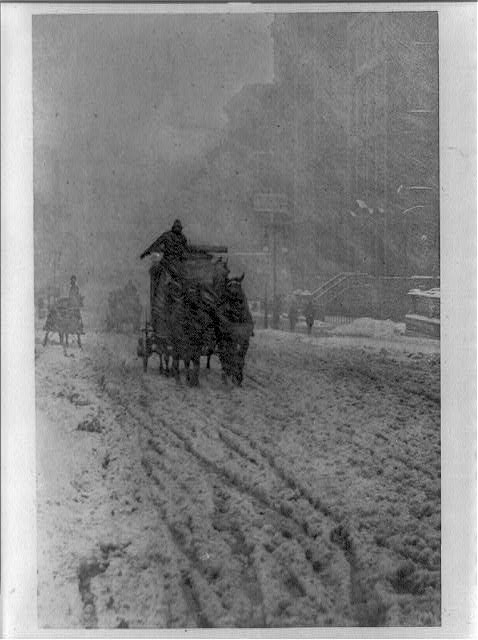

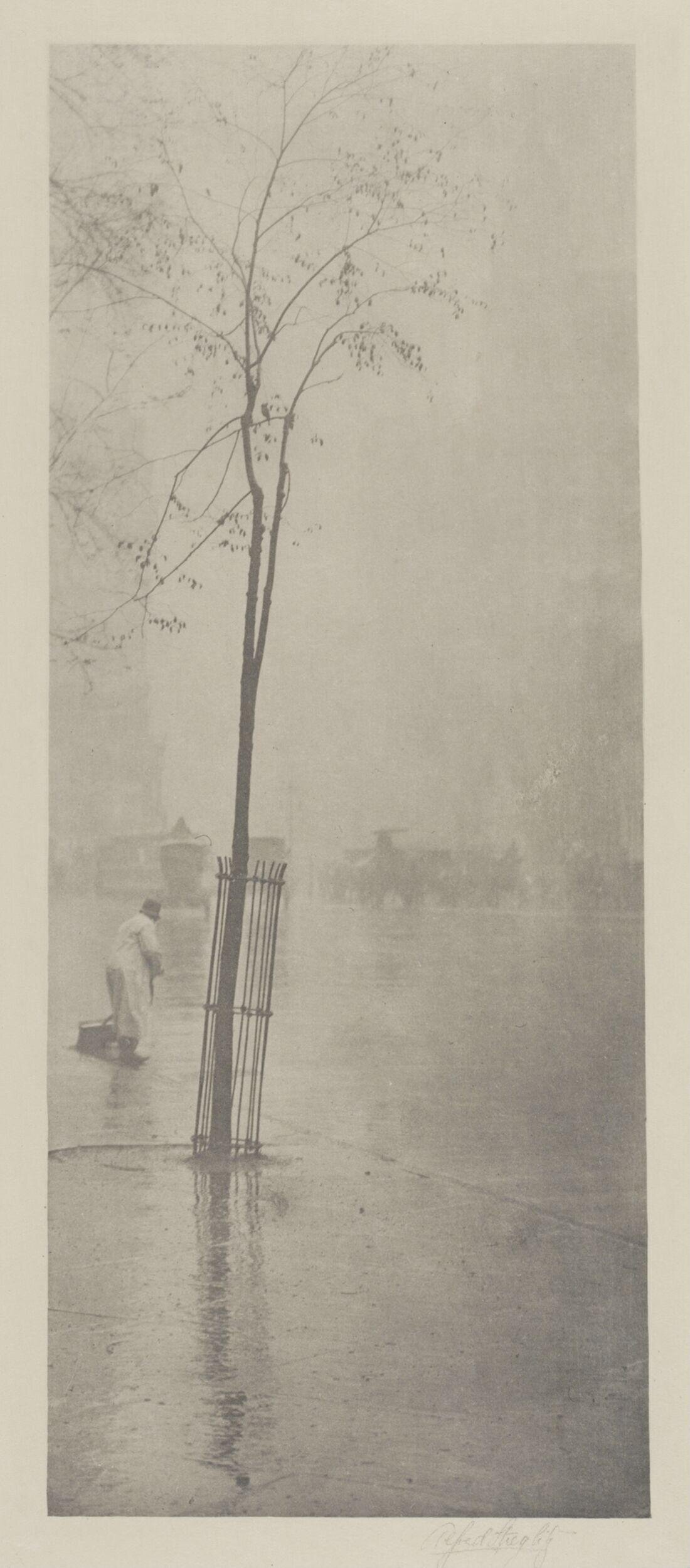

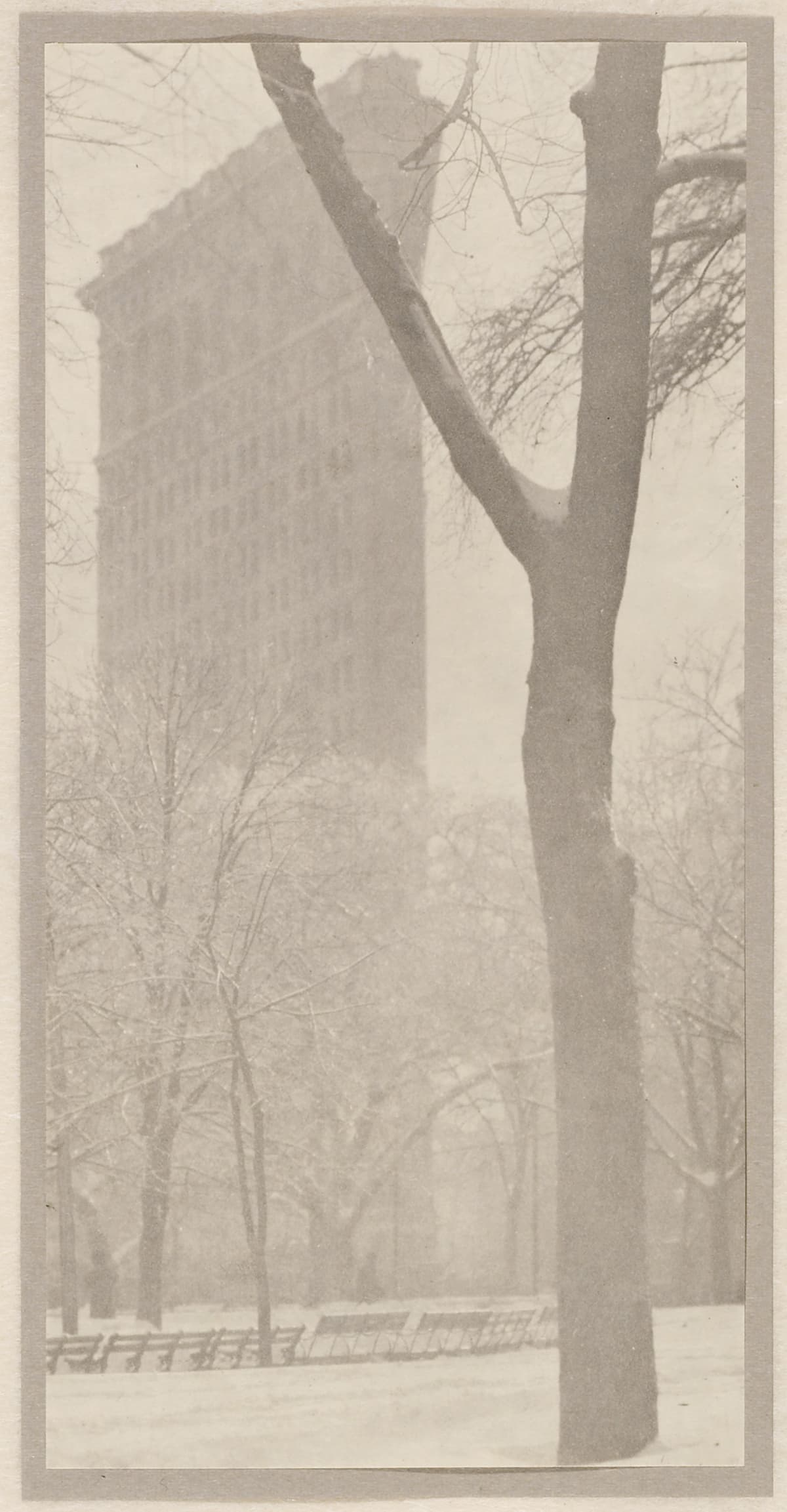

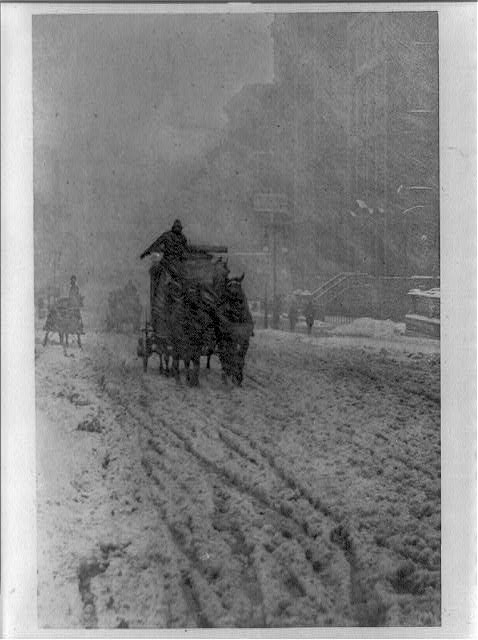

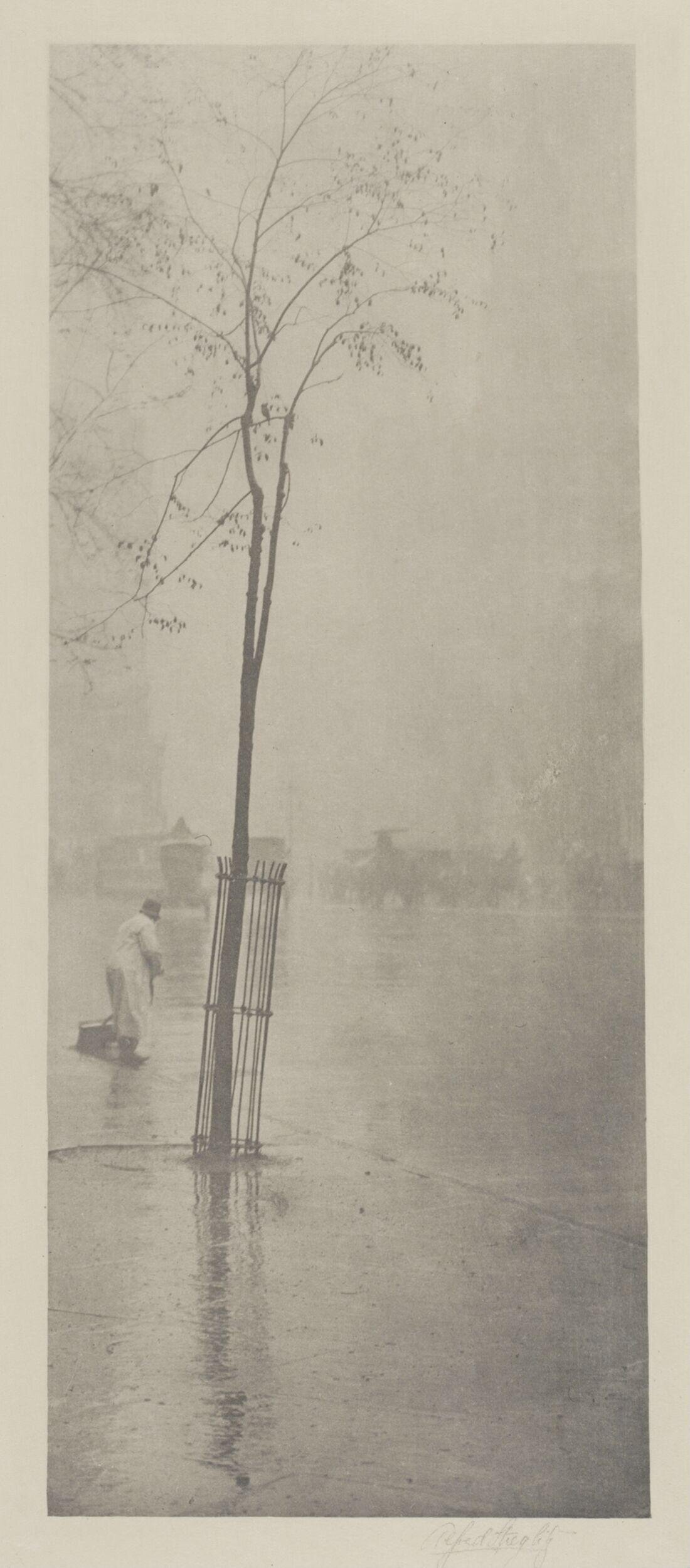

During his years in Europe, Stieglitz made photographs that demonstrated both technical virtuosity and an unusual sensitivity to atmosphere and light. His early works — studies of peasant life in Italy, rain-slicked streets in Venice, and the grey skies of northern Germany — were influenced by the Pictorialist movement, which sought to elevate photography by emulating the soft focus, tonal effects, and subject matter of painting. Stieglitz won prizes in European competitions and gained a reputation as one of the most accomplished art photographers on the continent. When he returned to New York in 1890, he brought with him not only a portfolio of distinguished work but a burning conviction that photography deserved to be recognised as a fine art equal to painting, sculpture, and the graphic arts.

This conviction drove every aspect of Stieglitz's public life for the next half-century. In 1902, he founded the Photo-Secession, a group of like-minded photographers dedicated to advancing photography as an art form. The name, borrowed from the European Secessionist movements in painting, signalled a deliberate break with the amateur camera club culture that dominated American photography. The Photo-Secession included Edward Steichen, Clarence H. White, Gertrude Käsebier, and Alvin Langdon Coburn, among others. Its primary vehicle was Camera Work, the lavish quarterly journal that Stieglitz edited, designed, and largely financed from 1903 to 1917. Camera Work was not merely a photography magazine; it was a platform for the most advanced visual and critical thought of its time, publishing photogravures of extraordinary quality alongside essays by critics, artists, and writers.

In 1905, Stieglitz opened the Little Galleries of the Photo-Secession at 291 Fifth Avenue in New York — the gallery that became universally known simply as 291. Initially conceived as a space for exhibiting photography, 291 quickly expanded its scope under Stieglitz's restless curatorial ambition. Between 1908 and 1917, the gallery presented the first American exhibitions of works by Auguste Rodin, Henri Matisse, Paul Cézanne, Pablo Picasso, Constantin Brâncuşi, and Francis Picabia, introducing European modernism to American audiences years before the famous Armory Show of 1913. Gallery 291 became the crucible of the American avant-garde, a meeting place for artists, writers, and intellectuals who were reshaping the cultural landscape of the country.

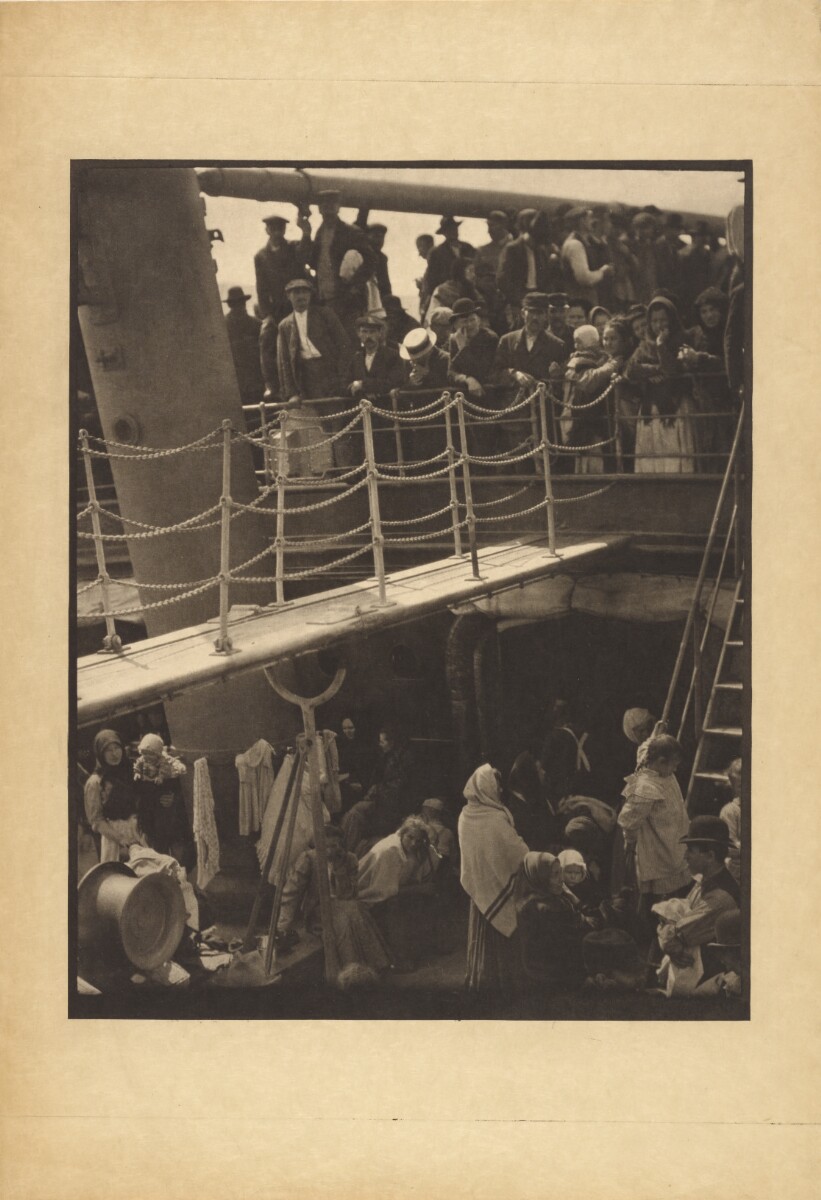

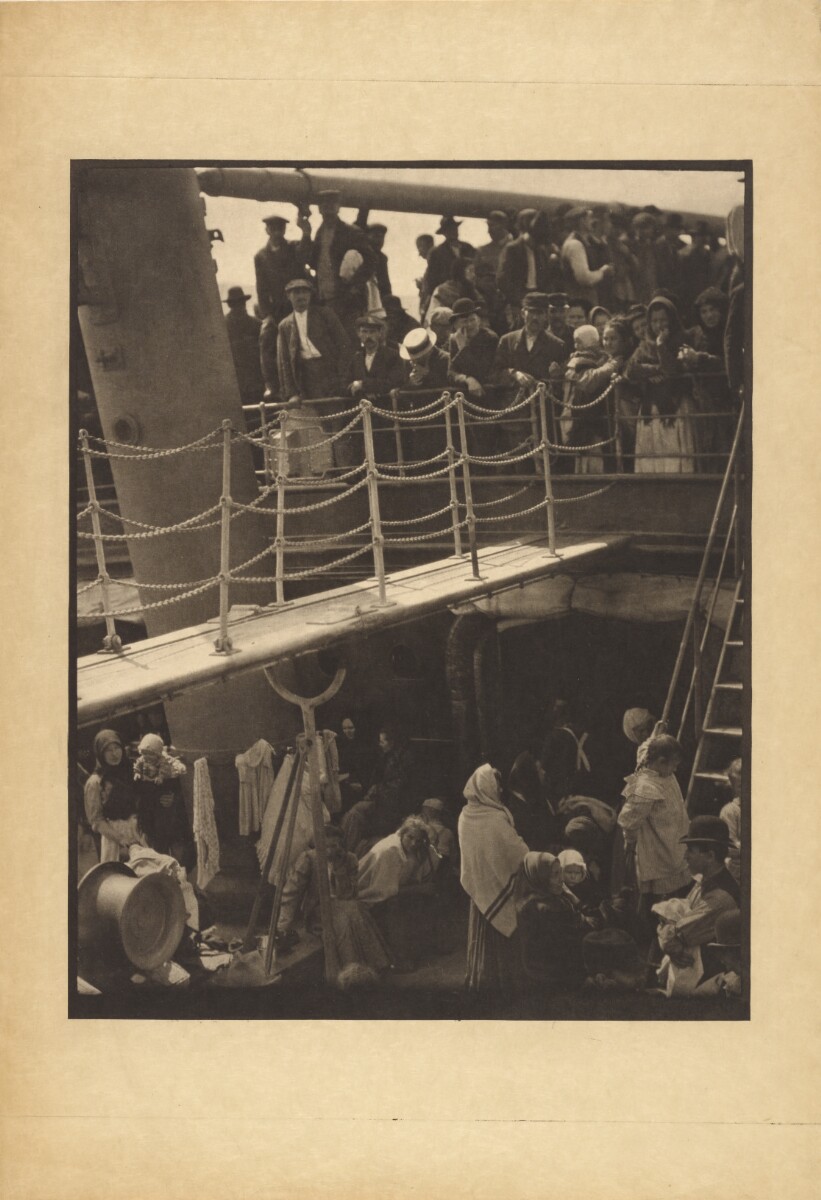

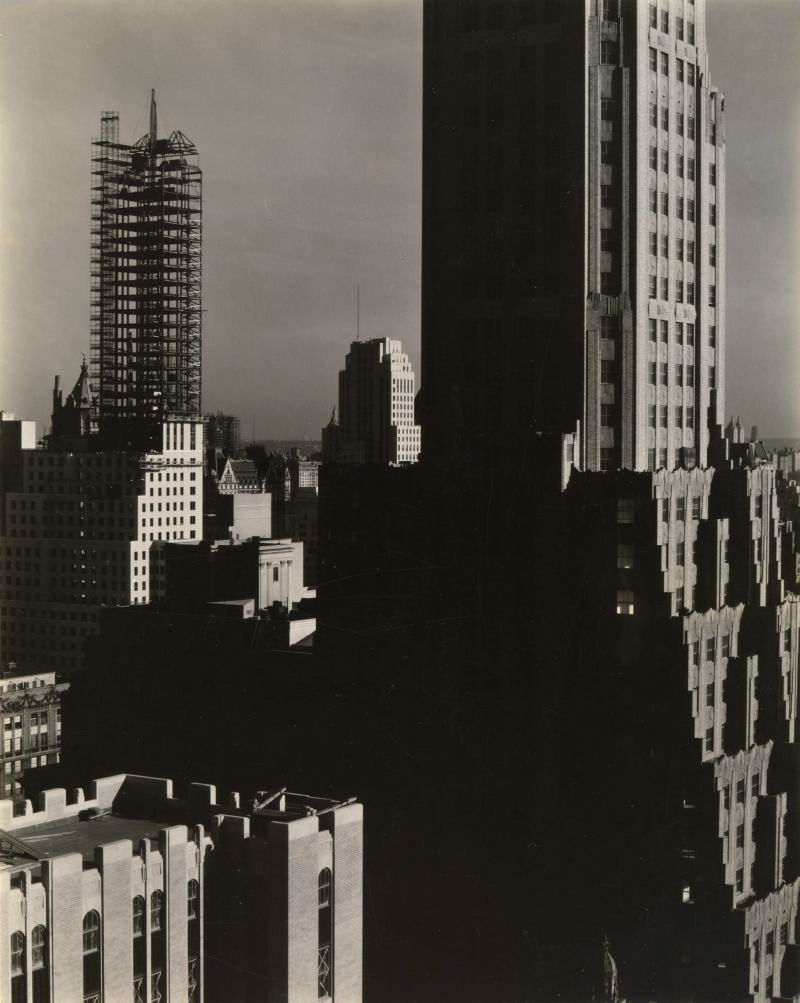

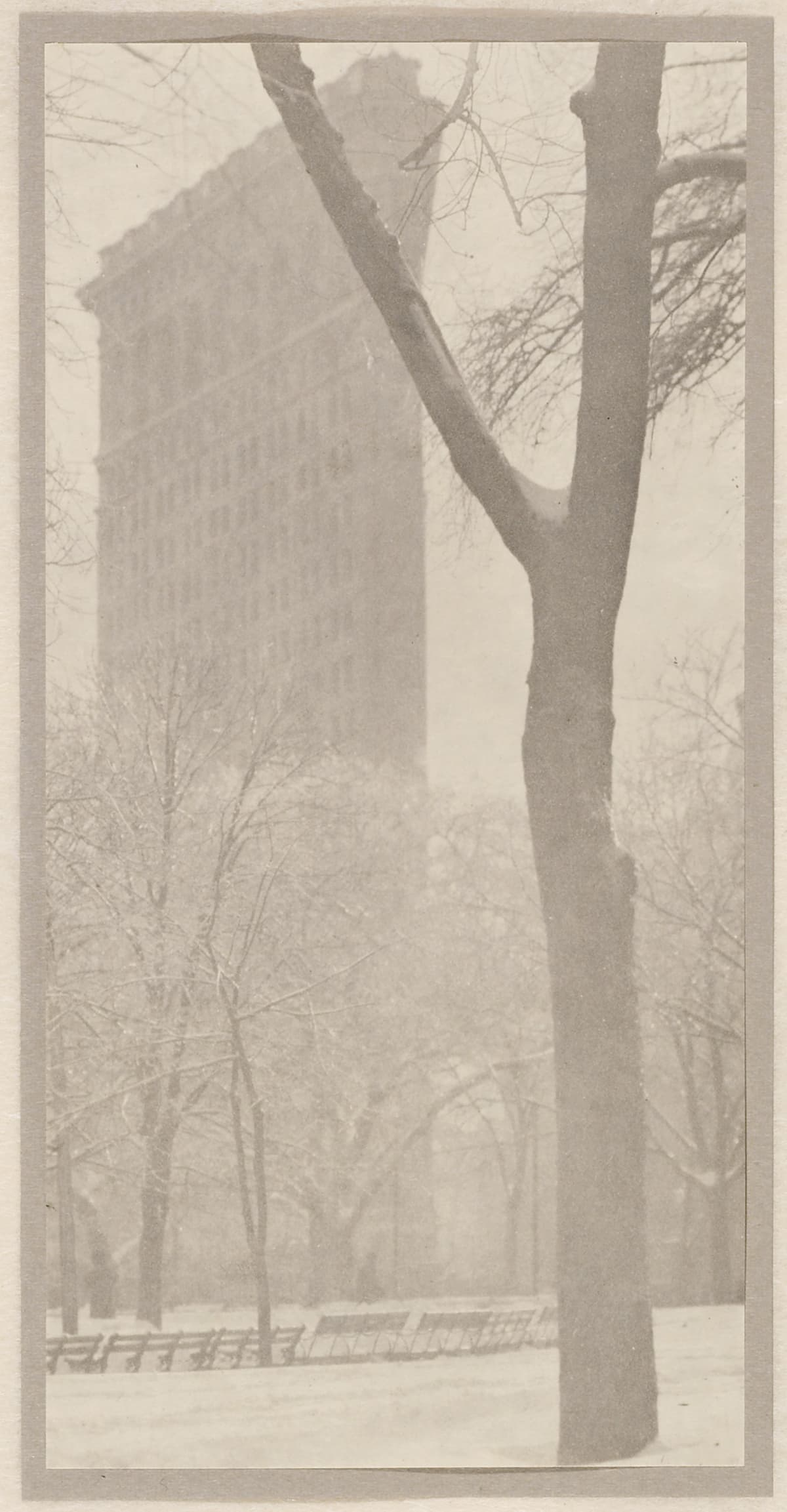

Stieglitz's own photographic practice evolved dramatically over these decades. By the 1910s, he had moved away from Pictorialism toward a sharper, more direct style that embraced the inherent qualities of the photographic medium rather than disguising them. His famous image The Steerage, made in 1907 aboard a transatlantic liner, is often cited as a turning point — a photograph whose power derives not from atmospheric effect but from the formal arrangement of shapes, lines, and tonal contrasts within the frame. In his later work, particularly the Equivalents series of cloud photographs made between 1925 and 1934, Stieglitz pursued a radically abstract vision, arguing that the emotional content of a photograph need have no connection to its literal subject matter. The clouds, he maintained, were not pictures of clouds but visual equivalents of his own inner states — a concept that anticipated the concerns of Abstract Expressionism by two decades.

From 1917 onward, Stieglitz's personal and artistic life became inseparable from that of Georgia O'Keeffe, the painter who became his muse, his most important artistic collaborator, and eventually his wife. His extended portrait of O'Keeffe, comprising over three hundred photographs made between 1917 and 1937, is one of the most ambitious and intimate portrait projects in the history of photography. The images range from close-up studies of her hands and face to full-length nudes and clothed portraits, together forming a composite image of a single person that is without parallel in its depth, duration, and psychological complexity.

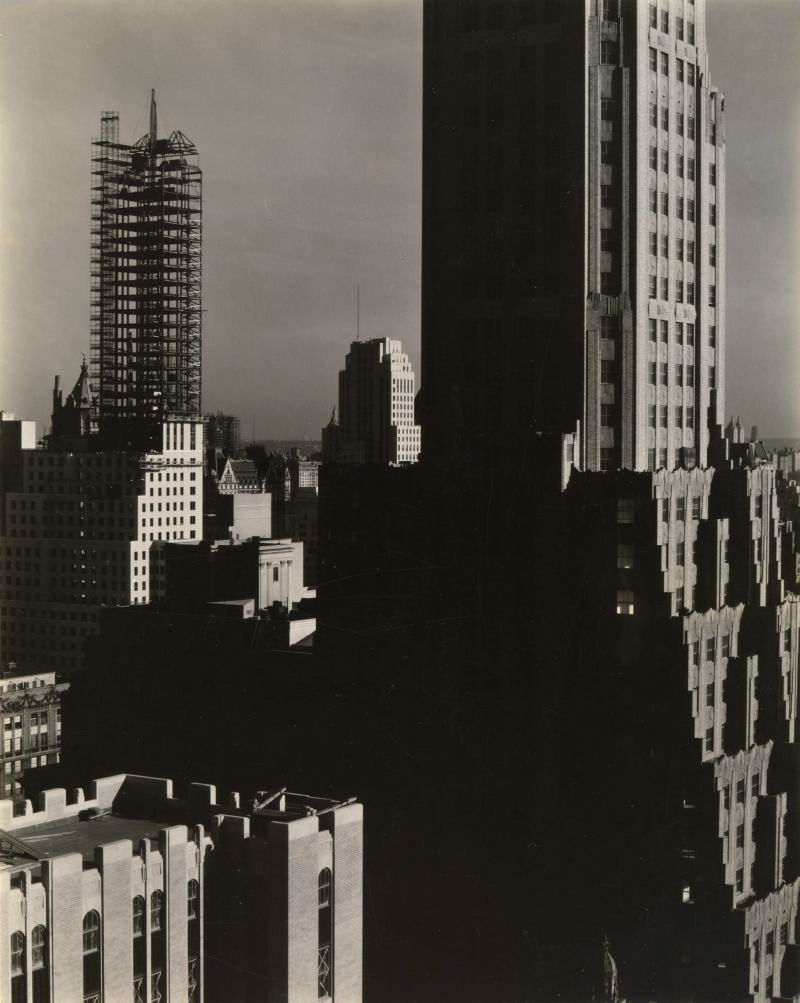

After closing 291, Stieglitz opened two further galleries: the Intimate Gallery (1925–1929) and An American Place (1929–1946), both dedicated to exhibiting the work of a small circle of American modernist artists including O'Keeffe, Arthur Dove, Marsden Hartley, John Marin, and Paul Strand. These galleries continued Stieglitz's lifelong project of creating spaces where art could be experienced with seriousness and attention, free from the pressures of commerce. He ran them with the same combination of idealism, stubbornness, and autocratic control that characterised all his institutional endeavours.

Alfred Stieglitz died on July 13, 1946, in New York City. His legacy is immense and multifaceted. As a photographer, he produced some of the most technically accomplished and emotionally resonant images of his era. As an editor and publisher, he created in Camera Work a publication of lasting beauty and intellectual significance. As a gallerist and impresario, he introduced European modernism to America and championed American artists who were reshaping the visual culture of the nation. Above all, he fought with unrelenting passion for the recognition of photography as a fine art — a battle that, largely because of his efforts, was definitively won during his own lifetime.

In photography there is a reality so subtle that it becomes more real than reality. Alfred Stieglitz

A photograph made aboard a transatlantic liner that Stieglitz considered his finest single image, valued not for its documentary content but for its formal arrangement of geometric shapes, lines, and human figures into a composition of extraordinary visual power.

A series of cloud photographs that Stieglitz presented as visual equivalents of emotional states, pioneering the concept of photography as pure expression and anticipating the concerns of abstract art.

A composite portrait comprising over three hundred photographs of the painter Georgia O'Keeffe, spanning two decades and encompassing an unprecedented range of physical and psychological intimacy.

Born on January 1 in Hoboken, New Jersey, the eldest son of German-Jewish immigrant parents.

Purchases his first camera while studying in Berlin. Studies photochemistry under Hermann Wilhelm Vogel.

Founds the Photo-Secession, a group dedicated to advancing photography as a fine art.

Launches Camera Work, the quarterly journal that becomes the most influential photography publication of the early twentieth century.

Opens Gallery 291 at 291 Fifth Avenue, New York, initially for photography but soon expanding to include European and American modern art.

Makes The Steerage, the photograph he would later call his most important single image.

Meets Georgia O'Keeffe and begins the extended portrait project that will span two decades. Gallery 291 closes.

Begins the Equivalents series of cloud photographs. Opens the Intimate Gallery in New York.

Opens An American Place, his final gallery, dedicated to a small circle of American modernist artists.

Dies on July 13 in New York City. His archive, including over 1,600 of his own photographs, is donated by Georgia O'Keeffe to the National Gallery of Art and the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Interested in discussing photography, collaboration, or just want to say hello? I’d love to hear from you.

Contact →